29 Painful Bladder Syndromes

Hypersensitivity or sensory disorders of the lower urinary tract in women have been poorly elucidated, and management has been mandated by anecdotal evidence. Reliable and standardized testing to make an accurate diagnosis remains elusive. These disorders represent a spectrum of symptoms and conditions that include chronic bacterial cystitis, urgency and frequency syndrome, “sensory urgency,” and urethral syndrome. The International Continence Society (ICS) recognizes this syndrome as genitourinary pain syndromes and syndromes suggestive of lower urinary tract dysfunction. This definition would include painful bladder syndrome, urethral pain syndrome, vulvar pain syndrome, vaginal pain syndrome, perineal pain syndrome, and pelvic pain syndrome. Ultimately, hypersensitivity disorders, pelvic pain syndrome, and interstitial cystitis (IC) remain diagnoses of exclusion. This chapter focuses on what may be the ultimate expression of this disease process: IC.

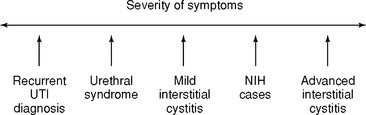

Hypersensitivity disorders affect most physicians’ practices. An estimated 15% of the 7 million women who experience a urinary tract infection (UTI) annually will have recurrences (greater than two episodes in 6 months or greater than three in 1 year). Of the 8.5 million women with urinary incontinence, about 40% have detrusor overactivity. More than 750,000 women have IC, and their quality of life is often lower than that of age-matched patients on renal dialysis. Significant clinical depression is present in 68% of these patients. In the absence of infection, patients with frequency, urgency, and pain are often classified as having one or more of the following: painful bladder syndrome, urethral syndrome, frequency and urgency syndrome, urethral instability, “sensory urgency,” or IC. These terms may represent one disease process in different phases or degrees of severity (Fig. 29-1). Appropriate classification is forthcoming, with current research efforts working toward defining etiology.

Figure 29-1 Spectrum of interstitial cystitis. NIH, National Institutes of Health; UTI, urinary tract infection.

INTERSTITIAL CYSTITIS

Epidemiology

The reported prevalence of IC varies greatly. Population prevalence estimates of IC have ranged from 30 in 100,000 to 501 in 100,000 of the total population (as many as 1 million Americans). Many of these studies were self-reported questionnaires and were not confirmed by medical record review. It is also important to note that diagnostic criteria were not established until 1987.

In 1987, for research purposes, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) established standardized diagnostic criteria for IC (Box 29-1). The National Interstitial Cystitis Data Base (ICDB), a cooperative multicenter longitudinal observation study group established in 1991, was sponsored to study the natural history of the disease and was based on a large population with symptoms consistent with IC. In 1999 the ICDB reported that the NIH guidelines were too restrictive to be used by clinicians. If the initial criteria were used, up to 60% of symptomatic women would not be diagnosed. Following an International Consensus in Kyoto, Japan, in April, 2003, the NIH assigned a panel to update the definition and management of IC. The guidelines are pending.

BOX 29-1 NIH-NIDDK DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA OF INTERSTITIAL CYSTITIS

Category A: At least one of the following findings on cystoscopy:

Category B: At least one of the following symptoms:

NOTE: These are the original criteria and are changing.

Gillenwater JY, Wein AJ. Summary of the National Institute of Arthritis, Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases Workshop on Interstitial Cystitis, National Institutes of Health. Bethesda, MD, August 28–29, 1987. J Urol 1988;140:203.

INFECTIOUS AGENTS

Extensive efforts have been made, with limited success, to establish an infectious agent as the cause of IC. Hunner (1915) first suggested a hematogenously disseminated bacterial cystitis as the cause. Most patients with IC report a history of UTI and have received several courses of antibiotics based on their symptoms, not on positive urine cultures. To date, no single bacterium, virus, fungus, or fastidious microorganism has been isolated as an etiologic factor in IC.

ULTRASTRUCTURAL ABNORMALITIES

Ultrastructural studies of bladder biopsy specimens following hydrodistention have revealed several distinct features. Abnormalities are observed in all tissue components of the bladder wall, including tissue cells, interstitial tissue, blood vessels, and intrinsic nerves. These features include urothelium with disrupted permeability barrier and accelerated turnover, abnormal profiles of detrusor muscle cells, and damage of intrinsic nerves and blood vessel walls. Significant fluid engorgement, with diffuse or loculated edema of tissue cells and extracellular tissue, is also seen. Lymphocytes are the predominant component, distributed unevenly throughout the tissue. Activated mast cells are readily identified adjacent to intrinsic nerves, but they are less commonly seen near blood vessels and in the suburothelium. These distinctive features are most prominent and extensive in biopsies from areas of glomerulations (submucosal hemorrhages) following diagnostic hydrodistention. These features, although recognizable, are less dramatic in severity and extent of distribution in biopsies from cystoscopically normal-appearing areas of the bladder lining. Further research has identified that urine from IC patients has a decreased level of heparin-binding epidermal growth-like factor (HB-EGF) and an increase in a putative antiproliferative factor. HB-EGF has been shown to increase toward normal values with hydrodistention. Antiproliferative factor and HB-EGF normalize following sacral neuromodulation. The abnormality in epithelial permeability/transitional dysfunction led to the development of the potassium sensitivity test.

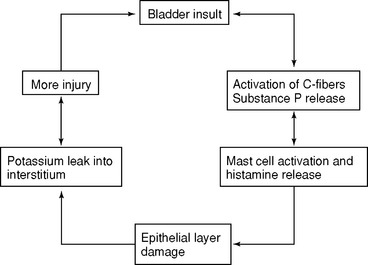

NEUROGENIC INFLAMMATION

Excitation of sensory nerves, especially small pain C fibers, triggers an inflammatory process through release of neuropeptides (substance P) and calcitonin gene-related peptide. Substance P causes vasodilation and increased vasopermeability and activates mast cells, causing injury with increased permeability of epithelial surfaces. Multiple events or factors trigger neurogenic inflammation. These include (1) bacterial cystitis or the antigen from the organism, (2) an increased level of estrogen, (3) toxins of endogenous and exogenous origin, including drugs, their metabolites, and certain foods, and (4) a potent mediator, such as the histamine released by activated mast cells. As our understanding of neurogenic inflammation and the role of mast cell activation progresses (Fig. 29-2), the diagnosis and treatment of IC will evolve.

Diagnosis

Painful bladder syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion (see Box 29-1). Patients cannot have evidence of cystitis caused by infection, use of cyclophosphamide or other chemical agents, radiation, or tuberculosis. Other infections, such as vaginitis, urethritis, urethral Ureaplasma, or genital herpes, cannot be present. Also, urethral diverticulum, bladder carcinoma, and carcinoma-in-situ must be excluded. However, patients with painful bladder syndrome may have concomitant lower urinary tract or pelvic floor disorders.

HISTORY

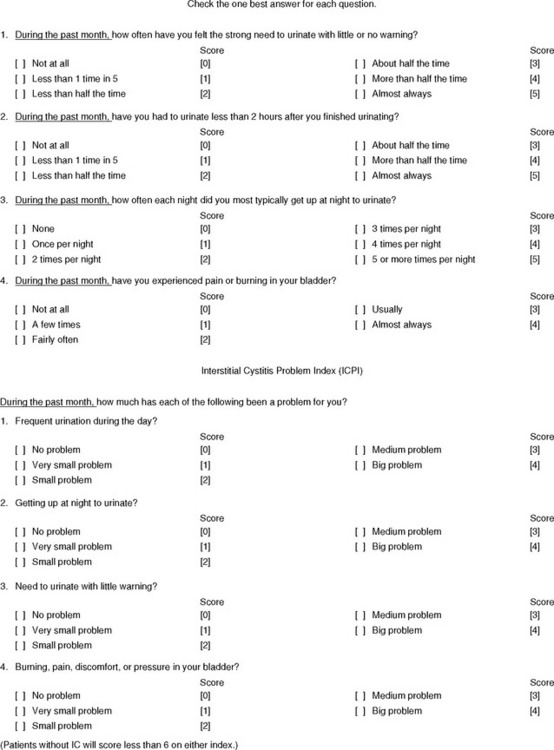

Frequency (greater than eight voids during waking hours), nocturia (greater than two voids during sleeping hours), urgency, suprapubic pressure on bladder filling, bladder pain, and dyspareunia are the most common symptoms. Secondary symptoms include burning during or after urination; a feeling of decreased bladder emptying; hesitancy; interruption of urinary stream; double voiding; referred pain to the abdomen, lower back, or medial thighs; abdominal bloating; postvoid urethral pain; incontinence without sensation; or detrusor overactivity. The severity and duration of each flare over the previous year should be recorded. The physician should also inquire about previous UTI, types of incontinence, parity, previous pelvic surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, previous treatments, menstrual history, history of endometriosis, central nervous system trauma, and dyspareunia. Commonly, patients initially present with one symptom only, urinary urgency/frequency, nocturia, or pain. All patients should be asked to do a voiding diary (see Fig. 14-1) and fill out the O’Leary-Sant symptom and problem index (Fig. 29-3). The recently validated pelvic pain urgency and frequency (PUF) questionnaire may also be used. A medical history should include associated diseases, such as migraines, fibromyalgia, sinusitis, drug hypersensitivity, sicca syndrome (dry eyes, dry mouth), Sjögren’s syndrome, vulvodynia, and irritable bowel syndrome.

POTASSIUM SENSITIVITY TEST

Parsons (1996) designed the potassium sensitivity test (PST) to measure epithelial permeability. Instilling a solution of potassium chloride (KCl) into a normal bladder will not promote urgency or pain (Box 29-2). If a patient’s bladder has a leaky epithelium, the KCl mixture readily diffuses across the transitional cells and stimulates sensory nerves, causing urgency and pain. Parsons demonstrated that 70% of patients with IC had provocation of symptoms, whereas only 4% of normal subjects responded with pain. A recent study showed that 84% of patients with a score of >14 of the PUF questionnaire had a positive PST.

CYSTOSCOPY

Cystoscopy is both diagnostic and therapeutic. Cystoscopy with hydrodistention of the bladder traditionally has been performed under general or regional anesthesia. Our experience has been that intravenous sedation, bupivacaine hydrochloride (Marcaine) bladder instillation, and pudendal nerve block are effective diagnostic and therapeutic alternatives with minimal morbidity and increased postoperative patient satisfaction. Cystoscopy is performed to eliminate other causes of persistent patient symptoms and hematuria and to examine for typical findings of IC (Table 29-1). The classic Hunner’s ulcer, an area of erythema with small vessels radiating to a central, pale scar after bladder filling, is found in only 8% of patients with IC. Previous biopsy sites and carcinoma in situ can be confused with ulcers. Before hydrodistention, an inclusive evaluation of the bladder is performed, and the degree of hypervascularity and linear scarring (mild, moderate, severe) is assessed. Hydrodistention is performed by filling the bladder under gravity at 80 cm H2O with urethral compression for 2 to 7 minutes. The bladder is then drained, looking for a terminal bloody effluent, and the capacity is measured (>350 mL is defined as early-stage IC and ≤350 mL as late-stage IC). The average bladder capacity for patients with IC has been reported as 575 mL and as 1115 mL for patients without persistent irritative voiding symptoms. On redistention of the bladder, the presence and severity of glomerulations, strawberry-like petechial hemorrhages, are determined. Not all patients with significant symptoms have glomerulations or a reduced bladder capacity. Bladder biopsy is performed after hydrodistention to reduce the risk of perforation. The biopsy eliminates the presence of carcinoma in situ and infection, and it can quantitate the number of mast cells in the lamina propria and detrusor muscle. The diagnosis of IC cannot be ruled out based on normal cystoscopic findings; the findings of glomerulations and a terminal bloody effluent suggest the diagnosis of IC. A capacity below 350 mL or the presence of a Hunner’s ulcer confirms the diagnosis of late IC. Concomitant laparoscopy may be performed when there is tenderness in the adnexa, a history of previous pelvic surgery, infertility, an abnormal pelvic ultrasound, suspected endometriosis, dysmenorrhea, or dyspareunia in the absence of vulvodynia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree