39 Outcomes And Quality-Of-Life Measures In Pelvic Floor Research

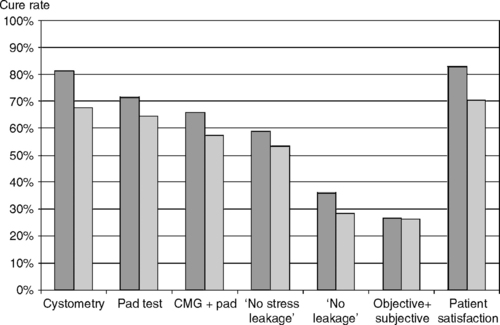

In contrast to trials evaluating treatment of cancer or cardiovascular disease, where mortality is an obvious clinically relevant primary outcome measure, choosing the appropriate primary outcome measure for clinical trials of pelvic floor disorders can be challenging because “success” of treatment is often difficult to define. For a condition such as urinary incontinence, it might seem obvious that the primary outcome measure for a therapeutic trial should be “continence,” but unfortunately it is not that simple. No clear consensus exists on how best to define continence. Should a therapy be considered “successful” if the patient reports that she no longer leaks urine but has developed voiding dysfunction or new-onset urinary urgency? Similarly, should a patient beconsidered “continent” if she reports no urinary leakage after treatment on a voiding diary but leaks urine on multiple occasions during a urodynamic evaluation or has a positive pad test? The outcome or outcomes chosen as the primary outcome measure of a study can have a profound impact on the study’s results. This is nicely illustrated by the UK TVT RCT, a multicenter randomized trial comparing tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) to Burch colposuspension for treatment of stress urinary incontinence (Ward and Hilton, 2002). The authors of this study defined “cure” as the absence of stress incontinence at urodynamics and a negative 1-hour pad test (both criteria had to be satisfied to be considered a cure). Under this definition, 66% of subjects receiving TVT and 57% of those receiving colposuspension were cured. Figure 39-1 illustrates how varying the definition of cure would have resulted in different cure rates. Using the absence of stress incontinence at urodynamic testing alone as the definition of cure would have resulted in cure rates of 81% and 65% for TVT and colposuspension, respectively, consistent with previous reports in the literature. In contrast, the cure rate would have been less than 40% for both procedures if the authors had chosen a patient report of “no urinary leakage” on a symptom questionnaire as the primary outcome measure. This example illustrates not only the impact of choice of outcome measure on study results, but also emphasizes the importance of choosing the outcome measure prior to the onset of the study. To wait until completion of a study to define “success” or “cure” would allow for considerable manipulation of results.

In spite of the recent effort by national and international organizations to standardize outcomes in studies of pelvic floor disorders, there is currently no clearly established single best outcome measure or group of measures for any of these conditions, hence the emphasis on assessing outcomes in many domains. Traditionally, there has been a tendency to use objective physician- or test-based measures, such as urodynamic outcomes for studies of urinary incontinence and physical examination for studies of pelvic organ prolapse, as the primary outcome variables in intervention trials of pelvic floor disorders. However, in the last decade there has been increasing emphasis on patient-based outcomes such as symptom questionnaires and quality-of-life assessments. In fact, a survey of physicians, nurses, and patients by Tincello and Alfirevic (2002) found that subjective measures and improvement in quality of life were regarded by all groups as the most important outcomes in urogynecology studies. In spite of this, subjective outcomes alone are inadequate to accurately characterize the effects of treatment on disorders of the pelvic floor. Both subjective and objective outcome measures should be assessed and the primary outcome should be chosen based on the study’s goal.

In this chapter, we will review many of the currently available outcome measures available to clinicians and researchers to assess the outcomes of treatment for pelvic floor disorders, including symptom diaries, pad tests, physical examination, physiologic tests such as urodynamics, symptom severity or bother questionnaires, quality-of-life questionnaires, and socioeconomic measures.

SYMPTOM DIARIES

The bladder or urinary diary is perhaps the most common outcome measure used in studies of urinary incontinence and other forms of lower urinary tract dysfunction. It is also a useful clinical tool (see Chapters 6 and 14. In its simplest form, a patient is asked to prospectively record the time and number of voluntary voids and incontinence episodes over a specified period of time, usually 1 to 7 days. In more complex forms, a subject may be asked to record pad usage, type and amount of fluid intake, voided volumes, frequency and severity of urinary urgency, and/or activities that occur in relation to her lower urinary tract symptoms. Subjects are also often asked to record the time that they go to bed and the time they awaken in order to distinguish daytime from nighttime symptoms. For research studies of urinary incontinence, the National Institutes of Health recommends a 3-day bladder diary that records and reports, at a minimum, pad usage, urinary incontinence episodes, and voiding frequency. Diaries in which patients are asked to report fluid intake and record voided volume using a graduated toilet insert are often called frequency-volume charts. Although more cumbersome for patients, frequency-volume charts do provide a significant amount of additional data about lower urinary tract function not available in simpler bladder diaries, including average daily fluid intake, total daily voided volume, mean voided volume, largest single void (functional bladder capacity), and daytime and nighttime voided volumes. Although diaries have been used primarily as an outcome measure for studies of urinary symptoms in the Gynecology and Urology literature, symptom diaries are used extensively in many areas of clinical research as well. For instance, they have been used frequently in studies of bowel dysfunction to record the frequency of bowel movements, fecal incontinence episodes, etc. Similarly, pain diaries are a standard outcome measure in studies of acute and chronic pain management.

The primary strength of symptom diaries, at least in theory, is that they avoid the biases and inaccuracies of memory recall and record a subject’s symptoms in their normal day-to-day environment. There is evidence, however, that many patients may not actually complete their diary prospectively. In a study of adults with chronic pain by Stone et al. (2003), subjects were asked to complete a pain diary for 21 consecutive days. Each of these “paper and pen” diaries was fitted with an unobtrusive photosensor that detected light and recorded when the diary was opened and closed. Subjects were asked to record their pain at three set time periods each day and were not informed of the presence of the photosensor. At the end of the study, subjects reported a greater than 90% compliance with the diary; however, the photosensor revealed that only 11% of subjects had filled out their diaries at the prescribed times. For most subjects, the records were marked by long periods, from days to weeks, when the diary was not opened even though entries were made for those days when the diary was turned in at the end of the study, suggesting that subjects frequently backfilled their diary to complete missing days. Such backfilling is particularly subject to retrospective biases. In this study, a parallel group of patients were given computer diaries that prompted them to complete their diary at the specified times and 94% true compliance was noted in this group, suggesting an advantage of computer diaries over paper ones. However, such computer prompting would not be useful for recording spontaneous events like voiding or incontinence episodes. In spite of this concern about retrospective completion of symptom diaries, they remain an important outcome measure in the study of pelvic floor disorders because of their widespread use, general acceptance, and proven reproducibility, particularly for studying lower urinary tract dysfunction. When a bladder diary or similar symptom diary is used in a study, time should be spent instructing the subject in the proper use of the diary and the importance of completing the diary in a prospective manner.

Another strength of symptom diaries is that they provide information on symptom frequency and, in some cases, severity, in a way that is quantifiable. This is particularly useful in studies of an intervention in which patients are not commonly “cured,” but may show an improvement in symptoms, such as studies of medical or behavioral therapy for urinary incontinence. In fact, bladder diaries are the most common primary outcome measure used in studies of this type. Furthermore, outcome measures that are continuous variables tend to provide greater statistical power than dichotomous variables, so using a variable from a bladder diary such as number of incontinence episodes per week rather than a dichotomous outcome such as “cure/failure” will usually allow for a smaller study sample size. An additional strength of bladder diaries in particular is that normal population values for variables like voiding frequency, mean voided volume, and daytime and nighttime urine output have been published, providing useful reference values for defining study populations and estimating treatment goals.

In addition to the possibility that symptom diaries may not always be completed contemporaneously, another potential weakness of this outcome tool is a lower patient compliance with completing symptom diaries when compared with simpler measures like questionnaires. In large pharmaceutical trials in which subjects are carefully selected and often financially compensated to participate, compliance with symptom diaries is typically high, often over 90%. In smaller less-funded studies, patient compliance with symptom diaries can be poor. Singh et al. (2004) prospectively studied 107 women who underwent pubovaginal slings. They used the Simplified Urinary Incontinence Outcome Score (SUIOS), a composite outcome that combines the results of a questionnaire, 24-hour pad test, and a 24-hour bladder diary into single score, as their primary outcome. Although all patients completed the questionnaire postoperatively, only 52% completed the symptom diary and/or the pad test even after repeated telephone contacts, reducing the number of subjects in whom the primary outcome was available to half the original study population. When considering using a symptom diary as an outcome measure, the advantages of this tool must be weighed against the possibility of poor patient compliance.

Another important consideration when using a bladder diary as an outcome measure is the therapeutic effect that dairy completion in itself may have on lower urinary tract function. As described in Chapter 14, bladder retraining using diaries is an effective intervention for both stress and urge urinary incontinence. Several authors have suggested that the high improvement rates seen in the placebo groups in pharmaceutical trials of overactive bladder and other similar trials (often greater than 40%) are due in part to a “bladder retraining effect” that occurs just by using diaries throughout the trial. Some studies suggest that this effect can occur as early as 4 days after starting diary use. When a bladder diary is used to evaluate the effect of an intervention, the only certain way of accounting for the therapeutic effect of the diary itself is to include a control group in the study.

PAD TESTING

The short-term pad tests each ask subjects to perform a set of standardized provocative maneuvers in the office that, depending upon the protocol, can last from 10 minutes to 2 hours. In an attempt to standardize bladder volumes, most short-term pad tests specify that subjects start the pad test with a symptomatically full bladder, drink a standardized volume of liquid, or have a standard volume of fluid instilled in the bladder prior to the test. A preweighed pad is then worn while performing a predefined group of activities that typically includes such things as walking, climbing stairs, jumping, bending, coughing, and washing hands over a specified period. The volume of urine loss is obtained by weighing the pad at the completion of the test. For short-term tests, a change in pad weight of greater than 1 g is considered positive. When a short-term pad test is used as a study outcome, the specific protocol used should be described. In 1983, the ICS recommended the 1-hour pad test (described in Box 39-1) in an attempt to standardize this outcome measure across studies. Compared with long-term tests, short-term pad tests are easy and quick, and patient compliance can be directly monitored. Because of this, they are used frequently in clinical trials. However, a significant disadvantage of short-term pad tests is that they lack authenticity. These office tests do not necessarily reproduce the activities or situations that result in urine loss in a patient’s everyday life. In fact, some patients may not be physically capable of completing all of the prescribed activities in the protocol. Another limitation of short-term pad tests is their poor test-retest reliability. Although some studies have demonstrated good correlation between short-term pad tests performed in the same subject on two separate occasions, many have found poor repeatability with this test. Lose et al. (1988) demonstrated differences of up to 24 g between two test results in the same subject 1 to 15 days apart using the ICS 1-hour pad test, and concluded that this test is not precise enough to allow reliable quantitation of urinary incontinence. This variation within subjects is largely attributable to differences in bladder volumes at the time of the test, and protocols that standardize pretest bladder volumes tend to have higher reliability.

BOX 39-1 STEPS OF THE 1-HOUR PAD TEST RECOMMENDED BY THE INTERNATIONAL CONTINENCE SOCIETY

(From: Abrams P, Blaivas JG, Stanton SL, Andersen JT: The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function. The International Continence Society Committee on Standardisation of Terminology. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl 1988;114:5.)