22 Otoplasty

Synopsis

Analysis. Analyze the problem in thirds.

Analysis. Analyze the problem in thirds.

Endpoint. Know what normal looks like, so you know your surgical endpoint.

Endpoint. Know what normal looks like, so you know your surgical endpoint.

Do not be destructive. Do not do anything to the ear that cannot be reversed.

Do not be destructive. Do not do anything to the ear that cannot be reversed.

Skin is precious but weak. Preserve skin in the sulcus and do not rely on skin tension to maintain ear position.

Skin is precious but weak. Preserve skin in the sulcus and do not rely on skin tension to maintain ear position.

Lobule. Consider lobule setback in every case.

Lobule. Consider lobule setback in every case.

Asymmetry. In asymmetric cases, operate on both ears most of the time.

Asymmetry. In asymmetric cases, operate on both ears most of the time.

Facelifts are otoplasties. Do not deform the tragus, lobule or sulcus.

Facelifts are otoplasties. Do not deform the tragus, lobule or sulcus.

Introduction

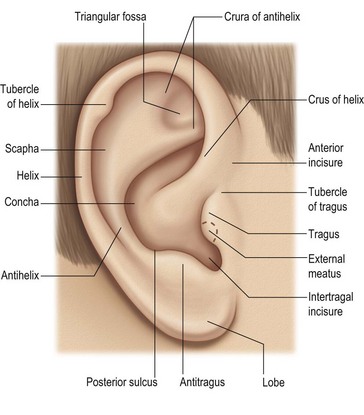

The single most important exercise for the surgeon, before performing any procedure in the otoplasty spectrum, is to have the characteristics of a normal ear firmly in his/her mind. With proper choice of technique, the surgeon can usually avoid the uncorrectable problems of over-correction and unnatural contours.1

History

Luckett2 recommended full thickness incision through the cartilage along the desired location of the antihelical fold. Converse and others3 described the combination of full thickness incisions parallel to the desired antihelical fold, with “tubing” sutures to create the fold. Various authors have recommended weakening of the cartilage along the fold, including Stenstrom4 who described anterior cartilage scoring in an effort to generate bending of the cartilage away from the cartilage abrasion. Most of these techniques included, or relied upon, skin excision in the retroauricular sulcus.

The current trend is toward less destructive methods of auricular reshaping, preservation of the retroauricular skin and concentration on natural, nonsurgical appearing results. The ultimate example of this phenomenon is neonatal, nonsurgical molding of the auricle, which can correct many of the deformities for which an otoplasty might later be recommended.5 Any surgical decision represents a trade-off and this author’s approach is no exception. The approach described in this chapter incorporates the bias that under-correction, recurrence and suture complications are preferable to over-correction, unnatural contours, sharp edges and unrepairable deformities.

Diagnosis/patient presentation

Patient selection

The degree of prominence/deformity and the age at presentation will determine when a surgical recommendation is made. For young children with very prominent ears and whose parents desire early correction, otoplasty is recommended as early as age 4 years. While there may be situations when earlier intervention is warranted, it is reasonable to view the age of 4 years as a minimum for most otoplasty procedures and its variations. In situations where the entire ears require reconstruction, as in microtia, this author prefers to follow the recommendations of Firmin6 and wait until approximately the age of 10 years.

Families frequently ask about the effect of early surgical treatment on growth of the ears. For whatever reason, this has never been an issue in this author’s experience. For one thing, there is a large variation in acceptable ear size. It has also never been shown that an otoplasty retards auricular growth. Finally, many prominent ears are on the large side and some growth retardation would be welcomed by the patient and/or the family (Fig. 22.2).

Treatment/surgical technique

Standard otoplasty for prominent ears of normal size

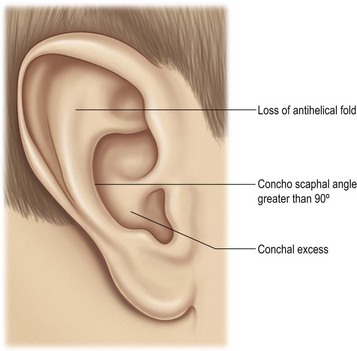

Correction (Fig. 22.3)

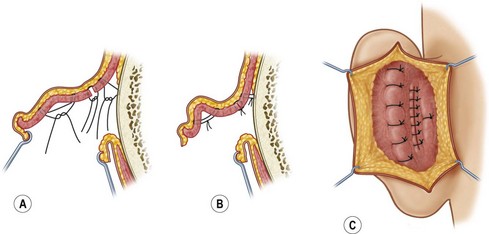

Mustarde concha-scapha and triangular fossa-scapha sutures are placed using 4-0 clear nylon sutures on an FS-2 needle.7 The number of sutures depends on the how far into the middle third of the ear the antihelical deficiency extends. In some cases the sutures will only be required in the upper third of the ear. In other cases, they will extend through the middle third as well. These sutures are placed in order to create a soft curvature to the antihelix and no attempt is made to correct the prominence of the ear at this point. The Mustarde sutures are not parallel to each other but, instead, are arranged like spokes on a wheel, all pointing toward the top of the tragus (center of the wheel). Care is taken to create a superior crus that curves anteriorly such that it terminates almost parallel to the inferior curs. If the superior crus is created such that it is a direct, cephalad extension of the antihelix (straight line), the result will appear unnatural and amateurish.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree