Optimizing Mastectomy Flaps Based on Breast Anatomy

Nolan S. Karp

Jordan D. Frey

Ara A. Salibian

History

The first reported radical mastectomy was performed in New York City in 1882 by Dr. William Halsted (1). Since the first description of this aggressive and morbid procedure, techniques for the surgical management of breast cancer have evolved to becoming less invasive while maintaining oncologic safety. This progression led to the development of the modified radical mastectomy, skin-sparing mastectomy, and finally the total skin-sparing, or nipple-sparing mastectomy (1). Each of these techniques, while different in terms of sacrificing or sparing certain structures, holds one aspect in constant: the separation of the breast gland from the more superficial breast skin and subcutaneous tissue. However, the precision required to perform this anatomic dissection, as well as its importance in maintaining mastectomy flap tissue perfusion, is often overlooked (1).

Maintaining mastectomy flap perfusion during mastectomy dissection may represent the most important factor in ensuring a successful ensuing immediate breast reconstruction. From superficial to deep, the breast is composed of skin, superficial subcutaneous fat, and a thin layer of superficial breast fascia (analogous to Camper fascia throughout the body) with an underlying deeper layer of adipose tissue (2,3). The underlying breast gland is separated from these superficial layers by a deeper fascial layer, also termed the breast capsule (2,3). This breast capsule is alternatively referred to as the superficial breast fascia. However, to avoid confusion with the thinner, more superficial layer of fascia between the two layers of subcutaneous breast fat, it is referred to herein as the breast capsule (Fig. 18-1).

After mastectomy, the remaining breast skin flaps are dependent on the subdermal plexus as well as perforators in the subcutaneous plane for perfusion (Fig. 18-2) (4,5,6). Anatomic dissection at the level of the breast capsule maximizes oncologic resection of the breast gland while also minimizing trauma to the skin flaps, thereby optimizing perfusion. Mastectomy dissection in a plane deep to the breast capsule thus risks incomplete oncologic resection. Meanwhile, overaggressive suprafascial dissection compromises blood flow to the mastectomy flap, risking ischemia changes with no oncologic advantage, as taking tissue above the breast gland offers no survival benefit (7).

Indications/Contraindications

The goal in reconstructive breast surgery is to provide the postmastectomy patient with a durable and aesthetic breast, whether that is utilizing implants or autologous tissue. However, even the most elegant reconstruction is condemned to fail if the overlying skin flaps are poorly perfused. Maintaining the viability of the native breast skin envelope through precise, anatomic mastectomy dissection is therefore critical in obtaining ideal reconstructive and aesthetic outcomes. While anatomic mastectomy dissection may be the most important factor in achieving a successful immediate breast reconstruction, it similarly may be the most difficult to assess clinically and scientifically investigate (8).

Given the oncologic and reconstructive significance of precise mastectomy flap creation, care should be taken in all patients to perform this dissection as anatomically as possible at the level of the breast capsule. This dissection is independent of the mastectomy procedure, whether being a total, skin-sparing, or nipple-sparing mastectomy. No matter how much skin will be taken, all remaining breast skin flaps should be created equally in the fascial plane. Similarly, there are no contraindications to this dissection. The goal of a mastectomy, again regardless of mastectomy procedure, is to remove the glandular breast tissue. This tissue lies below the level of the breast capsule; therefore, only tissue below this deep fascia should be removed in a patient-specific and anatomic manner, leaving the superficial subcutaneous tissue and skin intact. As will be discussed, various preoperative and intraoperative considerations can facilitate this dissection to ensure optimal outcomes.

Preoperative Planning

Execution of an anatomic mastectomy flap dissection with optimal perfusion begins with preoperative assessment

and planning. Various patient- and disease-specific risk factors for ischemic complications must be considered, including smoking, obesity, radiation, chemotherapy, as well as particular mastectomy incisions and mastectomy weight (9,10). These factors can contribute to the occurrence of ischemic complications even in the face of a perfectly dissected mastectomy flap. This underscores the importance of identifying such factors as much as possible preoperatively in an effort to make evidence-based decisions along with the patient as well as set realistic expectations regarding postmastectomy breast reconstruction. Protective measures should be preferentially pursued in patients at higher risk of ischemic complications. This may include offering non–nipple-sparing techniques, submuscular rather than prepectoral techniques, or even delayed reconstruction.

and planning. Various patient- and disease-specific risk factors for ischemic complications must be considered, including smoking, obesity, radiation, chemotherapy, as well as particular mastectomy incisions and mastectomy weight (9,10). These factors can contribute to the occurrence of ischemic complications even in the face of a perfectly dissected mastectomy flap. This underscores the importance of identifying such factors as much as possible preoperatively in an effort to make evidence-based decisions along with the patient as well as set realistic expectations regarding postmastectomy breast reconstruction. Protective measures should be preferentially pursued in patients at higher risk of ischemic complications. This may include offering non–nipple-sparing techniques, submuscular rather than prepectoral techniques, or even delayed reconstruction.

Selection of mastectomy incisions, particularly in nipple-sparing mastectomy, is another critical component of preoperative planning. As discussed, perfusion of the breast skin envelope after mastectomy is reliant on the subdermal plexus and subcutaneous perforators. All of this blood supply, after mastectomy, originates from the periphery of the breast. Placing a surgical incision on the breast further alters this perfusion. As the distance from the circumferential periphery of the breast to the edge of the mastectomy incision increases, marginal perfusion at the incision decreases. Further, surgical access to the breast differs depending on where an incision is placed. This can have significant impact on the technical facility of performing an anatomic flap dissection. The decision of what incision to utilize should be made in concert with the breast and plastic surgeon and may be based on tumor location, tumor size, prior scars, reconstructive modality, and/or patient preference.

In total and skin-sparing mastectomy, elliptical or circular incisions surrounding the nipple areola complex are generally chosen. These should be designed as central as possible such that it is equidistant from the periphery of the breast in all directions, maximizing perfusion in all breast quadrants. In larger breasts, designing a larger circle or ellipse can increase the amount of skin excised, effectively shortening the distance from skin edge to breast periphery. These incisions generally allow for excellent surgical access to both identify the breast capsule and dissect in this plane circumferentially in all directions.

The most common incision options in nipple-sparing mastectomy include inframammary fold, lateral radial, vertical radial, Wise pattern, and periareolar incisions (11). Inframammary fold incisions are placed along the

bottom of the breast, maximizing the distance from the superior breast periphery to the incisional margin at the inframammary fold. Perfusion can thus be tenuous in this area, notably in patients with large breasts. These incisions can also make dissection more tedious, especially in the superior quadrant due to limited access and requires greater experience for precise dissection in the correct, anatomic plane. Lateral and vertical radial incisions split the lateral or inferior quadrants of the breast in half. Perfusion in all directions is thus maximized while surgical access is superior to inframammary incisions for mastectomy dissection. Wise pattern incisions allow for skin reduction and excellent surgical access but maximize incisions on the breast and risk perfusion issues. Lastly, periareolar incisions disrupt perfusion to the nipple-areola complex and are not used in our practice (11).

bottom of the breast, maximizing the distance from the superior breast periphery to the incisional margin at the inframammary fold. Perfusion can thus be tenuous in this area, notably in patients with large breasts. These incisions can also make dissection more tedious, especially in the superior quadrant due to limited access and requires greater experience for precise dissection in the correct, anatomic plane. Lateral and vertical radial incisions split the lateral or inferior quadrants of the breast in half. Perfusion in all directions is thus maximized while surgical access is superior to inframammary incisions for mastectomy dissection. Wise pattern incisions allow for skin reduction and excellent surgical access but maximize incisions on the breast and risk perfusion issues. Lastly, periareolar incisions disrupt perfusion to the nipple-areola complex and are not used in our practice (11).

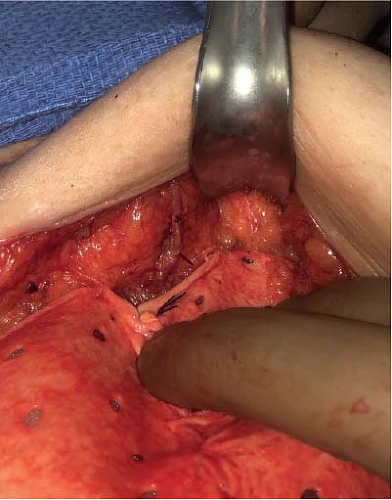

FIGURE 18-2 Intraoperative view of a subcutaneous perforator supplying the subdermal plexus after mastectomy performed in the anatomic plane of the breast capsule. |

Once oncologic and reconstructive plans have been established, the predicted thickness of the breast skin and subcutaneous tissue should be assessed. The perfusion of the skin flaps will largely be dependent on these layers given their dependence on the subdermal plexus and subcutaneous perforators after mastectomy. The thickness of this layer will inherently be variable among patients. Specifically, we have identified breast morphology and body-mass index as significant determinants of ideal mastectomy flap thickness (12). Patients with higher body mass index and larger mastectomy weights, as proxies for breast size, were found to have thicker mastectomy flaps with a more robust layer of subcutaneous fat (12). This highlights the need for an individualized approach to mastectomy flap dissection. The breast capsule layer is not at a constant depth across a patient population and therefore, mastectomy flap dissection is not “one size fits all.”

While predicted mastectomy flap thickness can be qualitatively assessed clinically in the preoperative setting based on breast morphology and patient examination, quantitative measurement can be difficult. The increased availability of preoperative breast imaging provides a unique opportunity to review and quantify each patient’s unique breast anatomy. Digital mammography can be utilized for this purpose; however, ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are more commonly utilized in our practice (8,12,13).

We believe in an oncoplastic approach to immediate postmastectomy breast reconstruction, relying on cooperative coordination being the ablative and reconstructive teams (14,15). At our institution, a majority of patients will have undergone preoperative MRI for oncologic planning. Therefore, each patient’s preoperative breast MRI can be reviewed by the breast and plastic surgeon. The distance from the breast skin to the breast capsule may be measured at multiple points in both the axial and sagittal planes (Fig. 18-3). This provides a quantitative

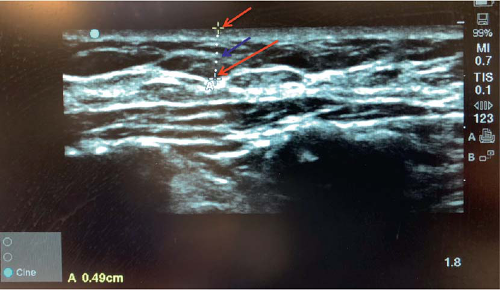

estimation of predicted mastectomy flap thicknesses based on each patient’s anatomy. Prior to infiltration of any dilute lidocaine with epinephrine solution in the operating room, hand-held ultrasonography may be utilized to confirm these estimated thicknesses using a second imaging modality in roughly the same locations as those measured on MRI (Fig. 18-4). We have found that this aids in the identification of the breast capsule intraoperatively, facilitating an anatomic mastectomy flap dissection in the optimal plane.

estimation of predicted mastectomy flap thicknesses based on each patient’s anatomy. Prior to infiltration of any dilute lidocaine with epinephrine solution in the operating room, hand-held ultrasonography may be utilized to confirm these estimated thicknesses using a second imaging modality in roughly the same locations as those measured on MRI (Fig. 18-4). We have found that this aids in the identification of the breast capsule intraoperatively, facilitating an anatomic mastectomy flap dissection in the optimal plane.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree