Open Treatment of Condyle Fractures

Michael Lypka

DEFINITION

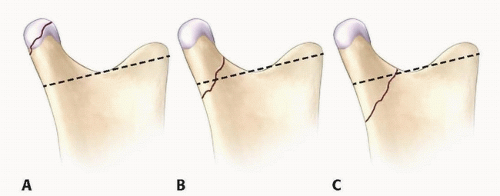

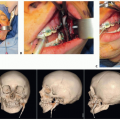

Condyle fractures of the mandible refer to a group of fractures involving the condylar head, neck, and base (FIG 1).1

There have been many classification schemes for mandibular condyle fractures; which classification system is best is debatable.

Important concepts relating to complexity of surgical repair would be the cranial-caudal position of the fracture (condylar head fractures are complicated), medial or lateral displacement of the proximal segment relative to the ramus (medially displaced are more difficult), and degree of displacement of the proximal segment from the mandibular fossa.

ANATOMY

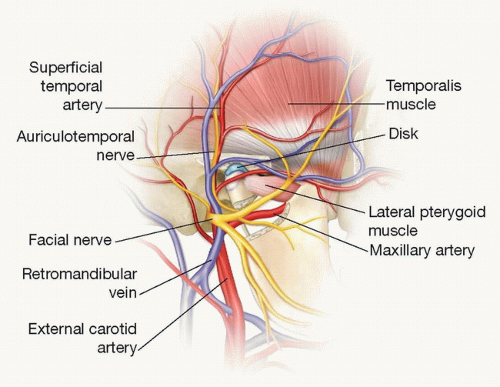

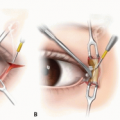

Knowledge of the anatomy of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and surrounding structures is critical if open treatment of condyle fractures is entertained. The decision to operate must be balanced with the potential risks of surgery, most importantly the risk to the facial nerve (FIG 2).

Temporomandibular joint (TMJ)

The TMJ is a symmetrically paired synovial articulation, which is the interface between the mandible and the base of skull.

The condylar head, with a lateral and medial pole, rests in the mandibular fossa, separated from the middle cranial fossa cephalad by a thin margin (approximately 1 mm) of bone. Anteriorly, the TMJ rests on the articular eminence of the zygomatic arch and translates along its slope with oral opening.

An ovoid biconcave avascular disk is interposed between the mandibular condyle and temporal bone, separating the TMJ into superior and inferior joint spaces, in which translation and rotation occur, respectively. The superior head of the lateral pterygoid muscle inserts into the anterior aspect of the disk, whereas the inferior head inserts onto the mandibular condyle. The disk transitions into an innervated network of connective tissue and blood vessels posteriorly, known as the bilaminar zone.

The joint capsule that surrounds the eminence and fossa blends with the periosteum of the zygomatic arch and condylar neck. It is thickened laterally to form the temporomandibular ligament or lateral ligament.

Vascular/nerve supply

The external carotid artery bifurcates into two terminal branches within the parotid gland; the superficial temporal artery, which ascends vertically along the posterior border of the condyle and forms anterior and posterior branches above the zygomatic arch, and the maxillary artery, which traverses the condylar neck on its deep surface toward the pterygopalatine fossa.

The auriculotemporal nerve provides sensory innervation to portions of the auricle, external auditory canal, tympanic membrane, and temporal skin, and runs parallel and posterior to the superficial temporal artery.

The superficial temporal vein lies superficial and posterior to the artery and then drains into the retromandibular vein, which runs posterior to the ramus of the mandible.

Parotid gland

The parotid gland, encapsulated by the parotidomasseteric fascia (parotid capsule), lies directly over the TMJ capsule.

The gland contains facial nerve branches coursing through it, as well as the superficial temporal artery and retromandibular vein.

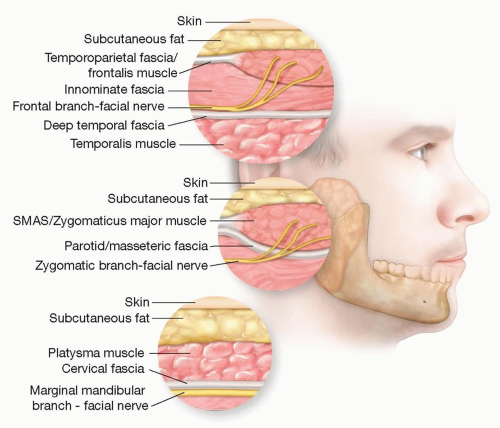

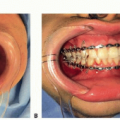

Relevant fascial layers (FIG 3).

Deep to the skin, in the temporal region, lies the temporoparietal fascia (TPF) or superficial temporal fascia. Anteriorly, this layer is continuous with galea/frontalis. The TPF is continuous caudally in the parotid region with the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS). In the neck, the SMAS is continuous with the platysma muscle.

A layer deeper, in the temporal region, is the innominate or subgaleal fascia. The temporal branch of the facial nerve lies in this plane, deep to the TPF. The parotidomasseteric fascia in the parotid region is continuous with the innominate fascia above and the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia in the neck. The marginal mandibular branch lies within or just deep to this cervical fascia.

The temporalis fascia overlying the temporalis muscle, splits into superficial and deep layers above the zygomatic arch, containing the superficial temporal fat pad, before inserting onto the zygomatic arch.

Facial nerve

The facial nerve emerges from the stylomastoid foramen and curves anteriorly into the parotid gland. It bifurcates within the parotid gland into temporofacial and cervicofacial branches, ultimately giving rise to five terminal branches: temporal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical. There are many interconnections between buccal and zygomatic branches but not the temporal and marginal mandibular branches, thus requiring special attention during surgical exposures involving these branches.

The temporal branch runs deep to the TPF, crosses the zygomatic arch, and lies anywhere from 8 to 35 mm anterior to the external auditory canal.2

The marginal mandibular branch, of significance in the Risdon approach, lies in or deep to the superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia. It may course below the angle of the mandible (upwards of 1.2 cm). Anterior to the facial vessels, the marginal mandibular nerve is almost always above the inferior border.3,4

PATHOGENESIS

Condyle fractures are sustained from either an axial load or a lateral impact.

A patient who sustains an impact to the chin transmits forces to the base of the skull resulting in bilateral condyle fractures, often with a concurrent symphysis fracture.

A lateral impact results in ipsilateral condyle fracture and concurrent contralateral body fractures.

NATURAL HISTORY

Untreated condyle fractures typically will heal without treatment (meaning that bony union will occur), but sequelae such as malocclusion, TMJ pain, or rarely ankylosis (less than 0.5 per 1000)5 can occur.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The mechanism of injury should be ascertained. An impact to the chin, as in a fall directly onto the chin, should elicit suspicion for bilateral condylar fractures with possible symphyseal fracture. A lateral impact (punch to the face) may result in a condyle fracture on the side of impact.

Change in occlusion, preauricular pain, concussive symptoms, and limitations of mouth opening are important historical data.

Physical findings

Limited mouth opening: deviation to the side of fracture on opening

Change in occlusion

Premature molar contacts on the side of fracture or lateral open bite on the opposite side.

Anterior open bite in bilateral condyle fractures due to loss of vertical height

Occlusal canting

Facial asymmetry due to loss of height on the fractured side

Tenderness to palpation over the fracture sites in preauricular area

Blood in external auditory canal—signifies fracture of cartilaginous wall of EAC

Submental lacerations

Cervical spine tenderness (concomitant injury in approximately 5% of mandible fractures)

IMAGING

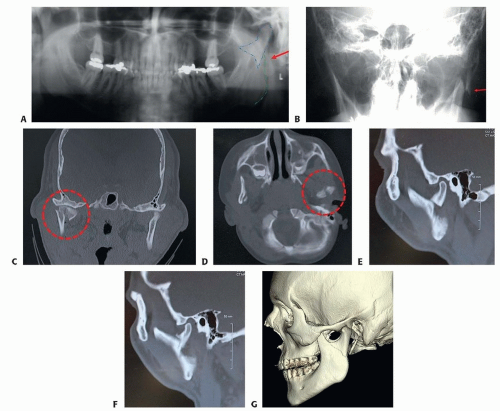

Orthopantomogram is a useful x-ray that identifies most condyle fractures and provides an overview of teeth and bony structures, often giving additional information about occlusion (FIG 4A).

Reverse Towne’s view: This plain film, taken from posterior to anterior with the neck flexed, is a useful adjunct to the panorex to identify condyle fractures (FIG 4B).

CT scans have become the standard for imaging of the maxillofacial skeleton in facial trauma and are indispensable in diagnosing and treatment planning for various types of condyle fractures.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree