One-Stage Nasolabial Skin Flaps for Oral and Oropharyngeal Defects

R. A. ELLIOTT

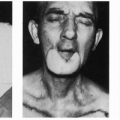

The nasolabial region is a well-known donor site for a variety of flaps. In most older patients, this area can yield a sizeable flap without significant distortion. When the flap is based inferiorly, the beard usually can be avoided, and when the flap is carried on a subcutaneous pedicle, one-stage repair of many oral and oropharyngeal defects is feasible.

INDICATIONS

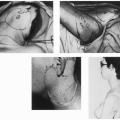

The nasolabial skin flap is quite versatile. Numerous authors have extolled its virtues for repair of ipsilateral surgical defects of the palate and a variety of other intraoral defects. Until the 1970s, most employed two-stage procedures and protected the

flap with a bite block (1, 2, 3, 4). Development of a safe one-stage technique enhanced its value significantly, particularly in the edentulous patient. The repair of antral fistulae, prompt rehabilitation of elderly and poor-risk patients, and combination with radical neck dissection became more routine, and bilateral flaps were interdigitated to repair defects of the anterior floor of the mouth and liberate the tongue (5).

flap with a bite block (1, 2, 3, 4). Development of a safe one-stage technique enhanced its value significantly, particularly in the edentulous patient. The repair of antral fistulae, prompt rehabilitation of elderly and poor-risk patients, and combination with radical neck dissection became more routine, and bilateral flaps were interdigitated to repair defects of the anterior floor of the mouth and liberate the tongue (5).

ANATOMY

The facial artery enters the face lateral to the mandible at the anterior border of the masseter and passes upward and forward on a tortuous course to the corner of the mouth, giving off the inferior labial artery branches, which supply the base of the flap and adjacent muscles. Although not dissected in this operation, the facial artery can be mobilized readily until it becomes fixed beneath the risorious and zygomaticus major muscles near the mouth. After giving off the superior labial artery deep to the latter muscle, a smaller main trunk passes on and through facial muscles to reach the inner canthus. No vessels enter the deep surface of the distal portion of the flap superiorly.

All named arteries are accompanied by one or more veins; most drain into the facial vein. The terminal branches of the facial nerve lie deep in the facial muscles and are not endangered by flap elevation superficial to the muscle, as recommended [see Operative Technique section]. Rich anastomoses between the facial vessels and the deep perforators of the infraorbital and transverse facial vessels further assure an abundant blood supply to and from the flap. Division of the facial artery at the level of the mandible, for example, during radical neck surgery, is not a limiting factor, primarily because of similar rich anastomoses between the facial, masseteric, and buccal vessels (6).

FLAP DESIGN AND DIMENSIONS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree