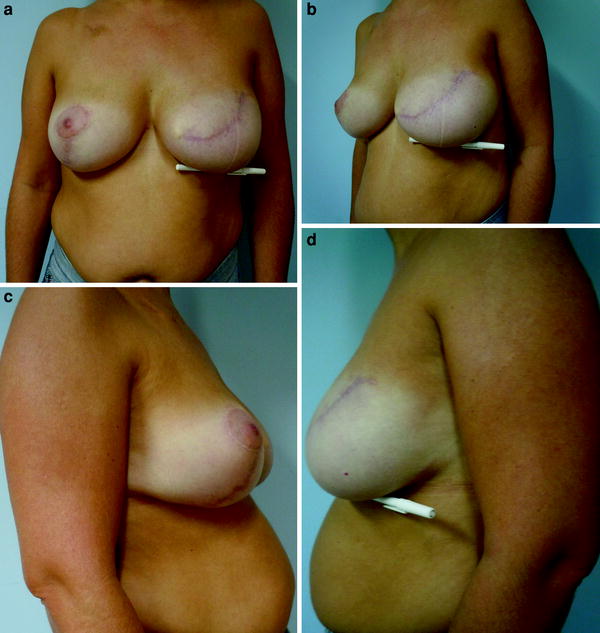

Fig. 22.1

a Preoperative view for a 38-year-old patient with invasive ductal carcinoma in the left breast (T2N0). b–e Postoperative images 1 year after a nipple-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction with an anatomic form-stable implant

Fig. 22.2

a Preoperative example of right-sided skin sparing mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction with a definitive anatomic prosthesis and a partial muscular pocket. A left-sided mastoplasty for augmentation and correction of ptosis was planned. b, c Frontal and lateral views 3 months later

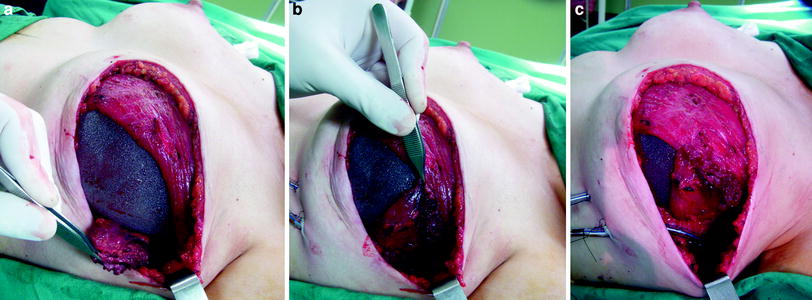

Fig. 22.3

Postoperative images 1 year after skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction with an anatomic form-stable implant and contralateral breast reduction in a large breast preserving some degree of natural ptosis

Multidisciplinary preoperative evaluation is necessary when deciding on the reconstructive technique and to assess the patient for possible oncologic contraindications to immediate breast reconstruction, including (Tables 22.1 and 22.2):

Table 22.1

Potential advantages of one-stage immediate breast reconstruction with definitive form-stable implants

Advantages |

|---|

A single procedure that can avoid a second surgery to change the temporary expander |

No donor site morbidity |

Short operative time and recovery |

Skin with similar color, texture, and sensation |

Table 22.2

Relative contraindications for one-stage immediate breast reconstruction with definitive form-stable implants

Characteristic | Difficulty |

|---|---|

Chest wall or skin infiltration | Adjuvant radiotherapy |

Aggressive tumors | Early start of chemotherapy and adjuvant radiotherapy |

Psychological problems | Incapacity to understand the limits and potential complications |

Several breast hypertrophy and morbid obesity | Increase in the levels of fibrinogen, prothrombin, and factors VII, VIII, IX, and X |

Previous irradiation | Higher risks of infection, bad aesthetic outcome, and loss of implant |

Tobacco | Higher risks of infection, wound healing problems and loss of implant |

Failed previous reconstruction with implants | Retraction |

Technical problems: tumor infiltration of skin or muscles, which complicates the technical performance of breast reconstruction with implants and is a formal indication for postoperative radiotherapy of the chest wall.

Risk of delay in adjuvant treatments: Patients with aggressive tumors (e.g., young patients with clinical and histopathologic evidence of rapid growth, and significant involvement of axillary lymph nodes) need to start the chemotherapy shortly after surgery. However, if the same patients have minor wound complications such as a local infection after biopsy, then one needs to consider the possibility that a major surgery could result in bilateral breast infection, which could delay the beginning of the oncologic treatment.

Psychological problems: It is appropriate to be observant of signs that suggest an underlying psychological issue that could impede the success of a reconstruction. Prior hospitalizations for psychiatric issues, inappropriate affect, and disorganized thought processes are just some of the red flags that could indicate a psychological disorder. Psychological assessment can be helpful to assist in appropriate patient selection and ensure that unresolved psychological issues do not derail the reconstruction, such as excessive expectations with breast reconstruction or difficulties to collaborate in the postoperative period, or even to accept complications and limitations.

Severe breast hypertrophy: This is as a relative contraindication because even with major reduction of mammary volume it can be very hard to obtain a satisfactory aesthetic result. Morbid obesity poses additional difficulties too.

Previous breast irradiation: Mastectomy due to a recurrence after conservative surgery with adjuvant radiotherapy is a relative contraindication. In these cases, the best option is the use of a musculocutaneous flap. It is possible to attempt an immediate reconstruction when the breast is small or when there are minimal sequelae from the radiotherapy (i.e., the skin is soft and pliable). Caution is advised and any attempt must be exhaustively discussed with the patient, with a focus on the high level of complications (cutaneous necrosis, exposure or dislocation of the prosthesis, and periprosthetic capsular contraction). There is a specific Chap. 42in this book on this topic.

Smoking: A significant association between smoking status and postoperative complications exists. Overall complications, reconstructive failure, mastectomy flap necrosis, and infection are commoner in smokers than in nonsmokers. Smokers who undergo postmastectomy expander/implant reconstruction should be informed of the increased risk of surgical complications and should be counseled on smoking cessation [7].

Failure of previous reconstruction with a temporary/definitive expander and/or implant: This can cause severe tissue retraction.

22.3 Preoperative Evaluation

A multidisciplinary team must evaluate patients who are candidates to undergo a breast reconstruction procedure before their being admitted to hospital. The preoperative evaluation considers reconstructive options and aims to choose the best technique for each situation. The patient is provided with detailed information on perioperative care and expectations. The assessment includes selecting the model, shape, and size of implants to be inserted. Our planning process includes photographs of the patient standing and preoperative drawings. Technical details such as the type of incision and oncologic details such as the need for any additional workup of the contralateral breast are determined at this time. Preoperative breast evaluation must include bilateral mammography and breast ultrasonography in combination with the physical examination to assess the extent of disease. We use breast MRI selectively (see the specific Chap. 3 on breast imaging). We routinely obtain a chest X-ray and abdominal and gynecological ultrasonography images. In select cases, we obtain images from staging studies such as a bone scan and a CT scan of the chest and abdomen. There are no specific therapies that need to be performed prior to the surgery. We use antibiotic prophylaxis, most commonly a cephalosporin, prior to skin incision. We re-dose the antibiotic intraoperatively in the limited number of procedures that last over 4 h [8].

22.4 Technique

The patient is placed on the operating table with both arms extended out on arm boards. This position allows two teams to work concomitantly whenever a contralateral procedure is planned, therefore reducing the surgical time. After completion of the oncology portion of the procedure, the site is cleaned with povidone–iodine or clorohexidine solution and the surgical instruments used in the oncology step are removed. An initial evaluation is made to check the integrity of the pectoralis major muscle, as well as the vascularization of the mastectomy skin flaps, and the inframammary fold. The degree of abduction of the arm is adjusted relative to the thorax to allow relaxation of the pectoralis major muscle. The table is flexed at the waist so that the patient’s thorax is raised 45°.

We have used three techniques for immediate breast reconstruction. The techniques have evolved in an effort to improve the cosmetic outcome:

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

1.

Immediate breast reconstruction with a complete muscular pocket This original technique was described by Little et al. [9] with the name “muscular bra”. The technique gave more protection to the implant in cases of limited skin necrosis and it allowed isolation of the axillary cavity and thus helps to limit migration of the implant toward the axilla. This was the only immediate reconstruction option available before the advent of form-stable implants. Prior to that, the only implants available where round, and that limited the options for improving aesthetic results. With anatomic form-stable implants, the technique for immediate reconstruction evolved because it is possible to achieve a better shape to the reconstructed breast if it is not laterally recovered by the serratus muscle as this allows better inferior and anterior projection. This creates a more natural shape to the reconstructed breast. However, there were two significant problems associated with eliminating the serratus portion of the muscular pocket. First, some mastectomy incisions, especially those that remove that nipple–areola complex as a horizontal ellipse, end up with the lateral part of the sutured incision directly on the implant with no intervening tissue. There is no protection of the implant in cases of skin necrosis and/or dehiscence of the scar. If this complication occurs, there is an increase in the risk of exposure of the implant, leading to removal. A second problem occurs with thin flaps with a fragile vasculature. In these cases, the complete muscular pocket places well vascularized muscle directly underneath the entire skin flap. This underlying muscle may help maintain the viability of the compromised skin flap. The layer of muscle may also reduce the tactile effect of “feeling” the implant, which is very frequent when the lateral skin flap is rather thin.

2.

Immediate breast reconstruction with a partial muscular pocket This technique started to be developed in the Plastic Surgery Department of the European Institute of Oncology in 2003, and at the Curitiba Breast Unit in 2004. It came about with the introduction of new anatomic form-stable implants and with the acceptance of a refinement of the mastectomy technique, which allowed preservation of nearly all the breast skin. The technical aim was to improve the cosmetic outcome of the implant reconstruction by eliminating the serratus portion of the muscular pocket but also to avoid placing the sutured incision directly over the implants. Incision placement is critical; as one wants to be sure that the final scar from the mastectomy can be placed completely on the pectoralis major muscle. One also wants to select patients where the final skin flaps will not be very thin and at risk of necrosis. With this technique it is possible to achieve a much more natural lateral contour of the breast (Fig. 22.4). The biggest drawback is the tactile feeling that patients have when they touch the inferolateral region of their breasts, as they can feel the underlying implant. With this technique, the lower and medial detachment of the pectoralis major muscle is performed as in the traditional technique (Fig. 22.5). After the definitive implants have been inserted, the lateral border of the implant pocket is formed by suturing the skin flap down to the musculature of the chest wall with an absorbable suture. It is critical to prevent both the lateral and the axillary migration of the implant. Lateral muscular cutaneous fixation is also needed in cases in which the breast base is too wide and when we have to insert an implant with a smaller base. This fixation also helps to avoid the lateral movement of the breast implant. In this case, suction drains to drain the whole cavity should be considered. When axillary dissection is performed, the risk of losing the implant is about three times higher than when only sentinel node biopsy is performed (unpublished data from the Curitiba Breast Cancer Unit). This could be related to surgical time, drains, and the alteration in postoperative lymphatic drainage. In these cases, a pectoralis minor flap can be useful to cover the lateral part of the implant and prevent implant malposition from dislocation to the axilla (Fig. 22.6).

Fig. 22.4

a, b Postoperative images 2 years after skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction with an anatomic form-stable implant and contralateral breast reduction with a partial muscular pocket. c–f Postoperative images 8 years later, demonstrating stability of the aesthetic outcomes

Fig. 22.5

Limits and localization of the implant in a partial muscular pocket

Fig. 22.6

Pectoralis minor flap technique to cover the lateral part of the implant and prevent implant malposition from dislocation to the axilla

3.

Immediate breast reconstruction with the cutaneous suspension technique This technique was described and developed by Rietjens et al. [10]. It uses a complete muscular pocket to allow implant coverage, but it also uses an abdominal advancement cutaneous flap with Mersilene mesh fixation to create a more natural inframammary fold with better inferior and external projection. The best candidate for this technique is a small-breasted woman with limited ptosis who does not need to have the contralateral breast corrected. The preoperative marking includes an assessment of the elasticity and mobility of the cutaneous tissues of the upper abdomen while the patient is standing. This assessment allows the surgeon to calculate the size of the cutaneous flap to be used. Afterward, both the current and the future inframammary fold are marked; the latter is marked between 4 and 6 cm below the current inframammary fold. After the mastectomy is completed, the reconstruction is started with the preparation of the complete muscular pocket: medial undermining of the pectoralis major muscle and lateral undermining of the serratus muscle. An extensive subcutaneous undermining is performed below the current inframammary fold extending down past the line demarcating the future inframammary fold. This dissection allows there to be adequate mobility of the cutaneous flap. Then, a mesh of nonabsorbable material (usually Mersilene, as it is durable and malleable) is used to fix the flap in place. The mesh is cut so that one of the edges is rounded off to a curve that will match the newly planned inframammary fold. This edge is sutured to the dermis and superficial fascia at the premarked new inframammary fold level with nonabsorbable stitches. They need to be well anchored to resist inferior traction. Taking these “healthy” bites can cause small skin retractions where the sutures are placed. In our experience, these retractions soften with time, and they eventually disappear as the skin heals and the periprosthetic capsule is formed. Once the mesh is fixed to the future inframammary fold, the mesh is pulled superiorly until the created fold comes to the same level as the contralateral side. The free edge of the mesh is then fixed with one or two nonabsorbable stitches on the fifth or sixth coastal cartilage, and the surplus of skin is removed. The implant is placed between the mesh and the pectoralis major muscle, and then the muscular pocket is completely closed with a suture between the lateral edge of the pectoralis major muscle and the anterior edge of the serratus muscle. Two drains are placed: one touching the implant, inside the muscular pocket, and the other draining the subcutaneous space and the axilla. It is advisable to keep the patient in a semisitting position (at 45°) as this lessens the traction on the sutures anchoring the advancement flap and thus lessens less postoperative pain. This technique can be applied to avoid the use of expanders when there is no need to remove large amounts of skin [11]. It avoids a second surgical step with general anesthesia. This technique has been used in 67 cases of immediate breast reconstruction and in six cases of delayed reconstruction. In 14 cases (19.2 %) it was necessary to perform a second surgery with general anesthesia for capsulotomy, replacement of the implant, and reconstruction of the nipple–areola complex. In three cases (4.1 %), the implant was removed because of exposure or infection. In 33 cases, only local anesthesia was needed for reconstruction of the nipple–areola complex, and for finishing the reconstructive phase. In this series, the capsular contracture was evaluated as Baker I in 24 cases, Baker II in 16 cases, Baker III in nine cases, and Baker IV in one case. The breast symmetry, the patient’s satisfaction, and the surgeon’s aesthetic evaluation were graded 7.56, 7.75, and 7.60 (with 1 representing extremely poor and 10 representing excellent) (Figs. 22.7, 22.8, 22.9, 22.10, 22.11).

Fig. 22.7

Evaluation of the amount of skin that can be used in the upper abdominal cutaneous flap

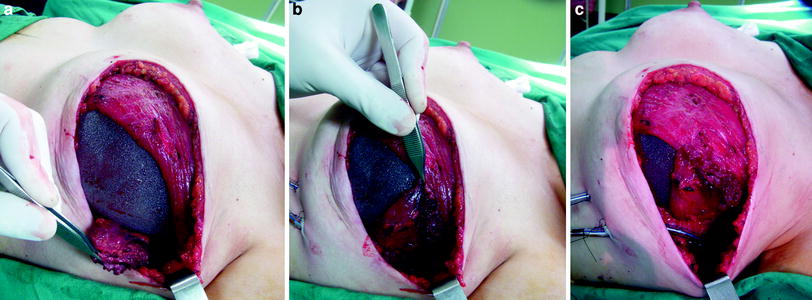

Fig. 22.8

Preparing the complete muscular pocket: pectoralis major muscle and serratus muscle