Facial analysis is an integral part of the surgical planning process. Clinical photography has long been an invaluable tool in the surgeon’s practice not only for accurate facial analysis but also for enhancing communication between the patient and surgeon, for evaluating postoperative results, for medicolegal documentation, and for educational and teaching opportunities. From 35-mm slide film to the digital technology of today, clinical photography has benefited greatly from technological advances. With the development of computer imaging software, objective facial analysis becomes easier to perform and less time consuming. Thus, while the original purpose of facial analysis remains the same, the process becomes much more efficient and allows for some objectivity. Although clinical judgment and artistry of technique is never compromised, the ability to perform objective facial photograph analysis using imaging software may become the standard in facial plastic surgery practices in the future.

Accurate facial analysis is one of the key components to proper surgical planning in facial plastic surgery. Consistent photographic technique and documentation is the cornerstone of critical preoperative analysis of the patient’s facial features. The gold standard of photography has long been known to be the use of a single-lens reflex (SLR) 35-mm camera. However, with advances in technology, digital photography has become an integral part of the facial plastic surgeon’s practice. Technological advances have allowed digital images to be archived and morphed with computer imaging software, which has led to the advanced capability for performing objective facial photograph analysis using imaging software.

Historical perspective

Proper facial analysis has always been a key component of the surgeon’s preoperative assessment. Such is the case in any surgical specialty in which a balanced harmony of facial features is important to the final aesthetic outcome. Holly Broadbent described one of the earliest standardized techniques for facial analysis. He detailed a method for taking consistent radiographs to obtain craniofacial measurements, known as cephalometry. Skeletal landmarks, measurements, and relationships were defined. Skeletal and soft tissue cephalometric analysis is still a useful tool for presurgical planning in orthodontic and orthognathic treatment.

Another approach to facial analysis was described by Bahman Guyuron, who used life-size photographs for soft tissue cephalometric analysis. During patient photography, he placed a removable marker on the patient to allow for a precise, full-scale, life-size photograph enlargement. Using drafting film overlying the photographs, Guyuron described a series of steps of drawn lines, measurements, and angles to critically analyze the patient’s frontal and lateral views for surgical planning of a rhinoplasty. By using soft tissue landmarks on the life-size photographs, he added that surgeons, who were not so artistically inclined nor had a keen eye for aesthetics, would be able to carefully analyze and predictably obtain optimal aesthetic outcomes.

Thus, whether using radiographs or photographs, guidelines were established for the ideal aesthetic facial proportions, which facilitated accurate facial analysis. Surgeons were then able to strike a balance between their artistry and their technical skill by objectively measured data points or analyses.

Advances in photography

In the early years, standard photodocumentation technique involved use of an SLR 35-mm camera. For a long time, 35-mm slide film had been considered to be the gold standard for clinical photography due to its superior image quality and resolution. However, as digital camera technology rapidly advanced, clinical photography shifted to digital. In a comparison of images between 35-mm film and digital technology, the image quality from digital cameras was statistically significantly superior when compared with the image quality of 35-mm cameras when variables such as subject matter, lighting, target distance, lens type, and sensor size were controlled. Furthermore, with digital imaging the additional advantages of lowering costs, archiving using less physical storage space, viewing images immediately, and in particular, imaging capabilities have made digital photography an invaluable tool for the facial plastic surgeon.

Advances in photography

In the early years, standard photodocumentation technique involved use of an SLR 35-mm camera. For a long time, 35-mm slide film had been considered to be the gold standard for clinical photography due to its superior image quality and resolution. However, as digital camera technology rapidly advanced, clinical photography shifted to digital. In a comparison of images between 35-mm film and digital technology, the image quality from digital cameras was statistically significantly superior when compared with the image quality of 35-mm cameras when variables such as subject matter, lighting, target distance, lens type, and sensor size were controlled. Furthermore, with digital imaging the additional advantages of lowering costs, archiving using less physical storage space, viewing images immediately, and in particular, imaging capabilities have made digital photography an invaluable tool for the facial plastic surgeon.

Computer imaging software

Imaging capabilities enable the facial plastic surgeon to perform an objective facial photographic analysis, which serves a variety of purposes such as: preoperative surgical planning, resident/fellow education, patient and surgeon communication, and outcomes research. A preliminary form of “imaging” was a free-hand drawing by the surgeon to depict the patient’s proposed surgical outcome. Another form of “imaging” was described by Guyuron, for which he drew proposed aesthetic outcomes on drafting film overlying full-scale, life-size photographs after analyzing the images according to ideal aesthetic facial proportions. Today, computer imaging software with digital camera technology has supplanted the need for the aforementioned techniques.

The most commonly used computer imaging software for facial plastic surgery include, in no specific order:

- 1.

MarketWise Hi-Res (United Imaging, Winston-Salem, NC, USA)

- 2.

Mirror (Canfield Scientific Inc, Fairfield, NJ, USA)

- 3.

Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems Inc, San Jose, CA, USA).

Another computer imaging software package recently developed by surgeons for a specific subsection of facial plastic surgery, rhinoplasty, is called Rhinobase. Rhinobase was developed using Borland Delphi Software (version 4.0 for Windows; Inprise Corp, Scotts Valley, CA, USA). Regardless of the brand of computer imaging software, the ideal software should include general applications for facial analysis, archiving images, and storing patient data, as well as morphing capabilities. Although a computer-savvy surgeon can perform many of the imaging techniques with readily available Photoshop-like products, the specific needs of other surgeons continue to fuel a market for newly designed imaging programs.

Objective facial analysis

Performing objective facial analysis on digital images requires that a standard photodocumentation technique is followed. Lighting, focal length, and positioning should be constant. The most common views obtained are frontal, lateral, oblique, and base views. In the frontal and lateral views, it is important to maintain the Frankfort horizontal plane (an imaginary line from the tragus to the inferior orbital rim that is parallel to the floor) when taking the photographs. For instance, subjects can be asked to look into a mirror straight ahead of them to naturally create a horizontal plane, which allows head positioning and eye gaze to remain consistent. However, the oblique view varies for surgeons depending on preference. When photographing the oblique view, some surgeons line up the tip of the nose with the edge of the opposite cheek; others prefer to align the medial canthus with the nasal ala. Finally, in the base view, proper patient positioning aligns the tip of the nose just between the eyebrows.

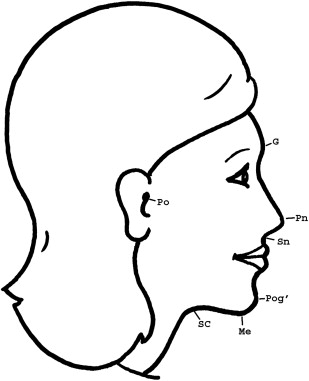

Using the measurement tool of the imaging software, the key landmarks for analysis are first chosen. Soft tissue counterparts for standard cephalometric landmarks and their definitions are as follows:

- 1.

(G) glabella, most prominent anterior point of the forehead

- 2.

(O) infraorbitale, lowest point on the inferior orbital rim

- 3.

(Me) menton, lowest point on the chin

- 4.

(Pog) pogonion, most prominent point on the chin

- 5.

(Po) porion, superiormost point of the external auditory canal

- 6.

(Pn) pronasale, anterior most point of the nose (tip)

- 7.

(SC) subcervicale, innermost point between the submentum and the neck

- 8.

(Sn) subnasale, point at which the columella meets the upper lip.

The Me, Pog, Po, and Sn are the soft tissue counterparts to cephalometric points, and are often labeled with a prime (eg, Pog′) ( Fig. 1 ). Additional common key analytical landmarks that can be used are included in Table 1 .

| G | Glabella | The most anterior portion of the forehead |

| Li | Labrale inferioris | The most prominent point on the prolabium of the lower lip |

| Ls | Labrale superioris | The most prominent point on the prolabium of the upper lip |

| Me | Menton | The most inferior point on the chin |

| N | Nasion | The deepest point in the frontonasal curve |

| O | Infraorbitale | The lowest point on the inferior orbital rim |

| Pog | Pogonion | The most anterior point of the chin |

| Po | Porion | The most superior point of the external auditory canal |

| Pn | Pronasale | The most prominent point on the tip of nose |

| SC | Subcervicale | Innermost point between the submentum and the neck |

| Sm | Supramentale | The deepest point of the mentolabial sulcus |

| Sn | Subnasale | The junction between the columella and the upper lip |

| Tri | Trichion | The hairline |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree