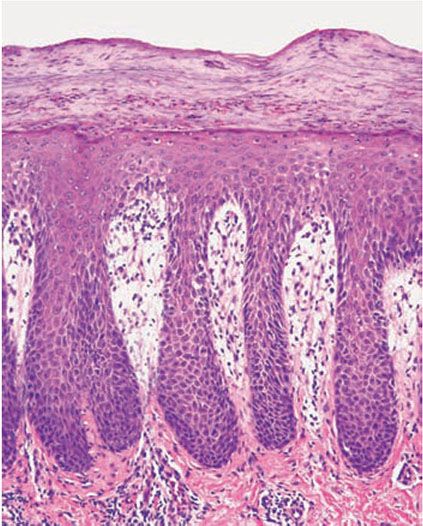

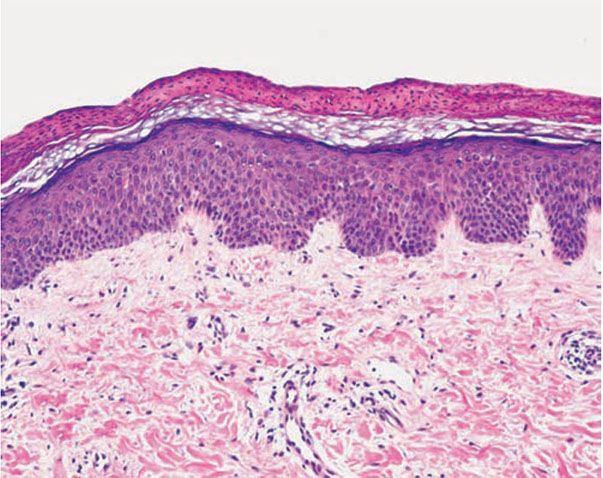

Figure 7-1 Urticaria. Sparse superficial perivascular and interstitial inflammatory infiltrate.

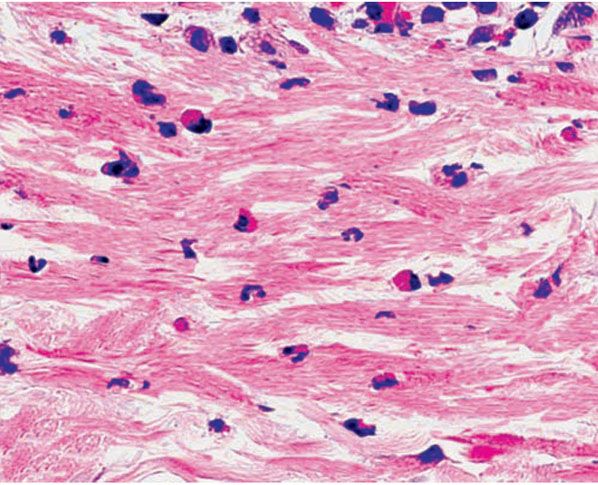

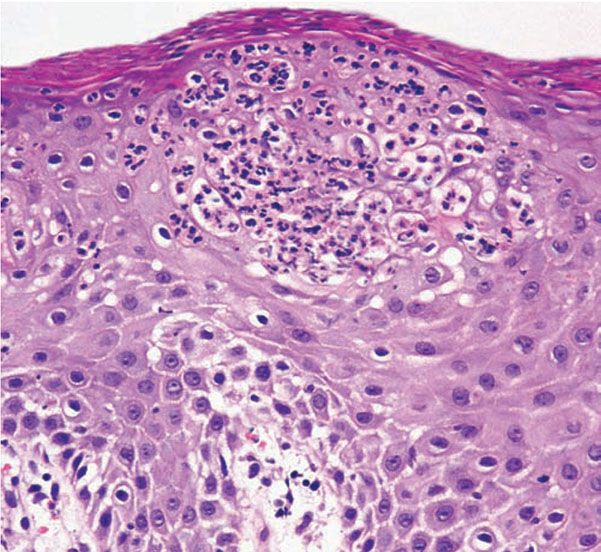

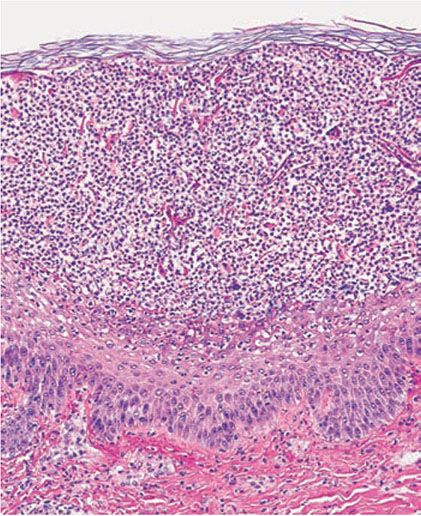

Figure 7-2 Urticaria. Interstitial infiltrate of eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes.

In angioedema, the edema and infiltrate extend into the subcutaneous tissue. In hereditary angioedema, there is subcutaneous and submucosal edema without infiltrating inflammatory cells (16).

In urticarial vasculitis, the dermis shows an early leukocytoclastic vasculitis characterized by (a) an infiltrate predominantly within and around the walls of small blood vessels composed largely of neutrophils, some of which show fragmentation of their nuclei (leukocytoclasis); (b) minimal fibrin deposits in the vessel walls; and (c) slight-to-moderate extravasation of erythrocytes (17).

Pathogenesis. Electron microscopic examination reveals mast cell and eosinophil degranulation in common urticaria. Tryptase and FXIIIa have been identified within the granules of mast cells (18). In chronic urticaria, immunoglobulin G (IgG) autoantibodies cross-link the α chain of the high-affinity receptor for IgE on mast cells (FcεRI), which results in histamine release. It appears that complement, especially C5a, augments histamine release (19,20). In addition, studies have shown that CD203c is a basophil activation marker that is upregulated by cross-linking of the FcεRI α-receptor and may serve as a useful marker to identify patients with chronic urticaria (21). Chemotactic mediators are released from mast cells that induce a sequential upregulation of endothelial adhesion molecules (P-selectin, E-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule 1 [ICAM-1], and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1) and of β2-integrins on leukocytes (22). The presence of these autoantibodies against the FcεRI α-subunit of the IgE receptor or IgE itself is detected in approximately 30% to 40% of patients with chronic urticaria (21).

Most patients with hereditary angioedema have a low serum level of the esterase inhibitor of the first component of complement (C1-INH). Exhaustion of this inhibitor allows activation of C1. This leads to activation of C4 and C2, with the generation of a C2 fragment possessing kinin-like activity and causing increased vascular permeability (3). A smaller proportion of patients with hereditary angioedema have a deficit in functional C1-esterase inhibitor.

Drug-induced angioedema has been reported to be most frequently triggered by β-lactam antibiotics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (23), and the increasing role of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) has been suggested as the cause of life-threatening angioedema (24).

In urticarial vasculitis, circulating immune complexes are found in about one half of the patients. By direct immunofluorescence testing, strong granular deposits of immunoreactants are seen along the dermoepidermal junction and perivascular areas (13,25). Positive immunofluorescence findings are more common in patients with the hypocomplementemic form of urticarial vasculitis (10). Renal biopsy in patients with hypocomplementemia frequently shows glomerulonephritis (7).

Differential Diagnosis. Clinical appearance and evolution of urticarial wheals are often very characteristic and diagnostic of the disease. Differential diagnosis of urticaria may include dermal hypersentivity reactions to drugs or insect bites, contact dermatitis, gyrate erythema and viral exanthema, or the urticarial phase of bullous pemphigoid.

The absence of epidermal changes and a mixed infiltrate of neutrophils and eosinophils favor the diagnosis of urticaria. A predominance of eosinophils within the inflammatory infiltrate is more common in drug and insect bite reactions (26), whereas lymphocytes prevail in gyrate erythemas and viral exanthems.

Principles of Management. Physical triggers (e.g., cold, overheating, pressure), nonspecific aggravating factors (e.g., stress, alcohol), and drugs with potential to worsen urticaria or angioedema (e.g., aspirin, codein, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories, ACEIs) should be minimized or avoided. Topical antipruritic lotions, such as calamine or 1% menthol in aqueous cream, can be soothing (27).

Nonsedating H1 antihistamines are the first-line treatment in most cases of acute urticaria. This category of drugs includes loratidine, cetirizine, desloratidine, and fexofenadine among others (28). In cases of more persistent or severe urticaria, H2 antihistamines may be added (29) and higher doses above the recommended maximal dose may be effective (27). When nonsedating antihistamines are no longer effective, other therapies should be tried, such as leukotriene receptor antagonists in combination with antihistamines (30), and oral immunomodulatory drugs, including corticosteroids, cyclosporine, dapsone, hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, and mycophenolate mofetil. Newer therapies include intravenous immunoglobulin and omalizumab (31). Intramuscular epinephrine can be lifesaving in anaphylaxis and in severe laryngeal angioedema (27), and patients with a suggestive history should be counseled to carry epi-pens for self-administration.

PRURITIC URTICARIAL PAPULES AND PLAQUES OF PREGNANCY

Clinical Summary. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP), also called polymorphic eruption of pregnancy, is a fairly common entity first described in 1979 by Lawley et al. (32). The condition has a predilection for primigravidas in the third trimester of pregnancy. The rash usually starts on the abdomen, sparing the umbilicus, and then spreads to proximal parts of the extremities and buttocks. The eruption may involve all parts of the body. It is composed of intensely pruritic erythematous urticarial papules, which may be surmounted by vesicles. There is no increased incidence of the rash in subsequent pregnancies (33). The rash usually involutes spontaneously after delivery. Fetal outcome appears to be unaffected. Unusual clinical presentations have been reported as involvement of palmoplantar surfaces and also initial manifestation of the disease in the postpartum period (34,35).

Histopathology. Microscopic findings most commonly show a superficial and mid-dermal perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with variable numbers of eosinophils and neutrophils together with edema of the superficial dermis. Epidermal involvement is variable and consists of focal spongiosis, parakeratosis, and mild acanthosis (32,33,36).

Pathogenesis. An association between PUPPP and increased maternal weight and twin/triplet pregnancies has been identified (37,38), suggesting a relationship between skin distention and the development of PUPPP (39). In cultures of human keratinocytes, lesional epidermis of PUPPP has shown positive progesterone receptor (PR) expression detected by immunohistochemistry and reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Nonlesional epidermis, however, has not revealed any PR positivity (40). In addition, a paternal factor hypothetically generated or expressed by the fetal portion of the placenta has been invoked as the cause of PUPPP in two families with unusual conjugal patterns (41). Direct immunofluorescence studies may be negative or show nonspecific immunoreactants on dermal blood vessels or at the dermoepidermal junction (42).

Differential Diagnosis. Specific dermatoses associated with pregnancy should be considered in the differential diagnoses and include pemphigoid gestationis, atopic eruption of pregnancy (AEP), and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (43).

Pemphigoid gestationis (PG) is a blistering dermatosis with a preliminary urticarial phase. Unlike PUPPP, it may develop on subsequent pregnancies and the rash often involves the umbilicus. Histopathologically, more eosinophils are present along the dermoepidermal junction in PG than in PUPPP. Direct immunofluorescence study usually shows linear deposition of C3 and IgG along the basement membrane zone in perilesional skin (44). While PUPPP has an indolent course, PG is associated with greater prevalence of decreased gestational age at delivery and low birth weight (45).

Patients with AEP usually have personal or familial history of atopic dermatitis. As opposed to PUPPP, skin lesions in AEP commonly start during early pregnancy. In intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, patients present with intense pruritus, skin excoriations and lichenification. Histologically, in both entities, epidermal changes such as acanthosis, hypergranulosis, and hyperkeratosis are much more pronounced due to chronic scratching (43).

Principles of Management. Because PUPPP tends to resolve spontaneously shortly after delivery, treatment is mainly focused on relieving the associated pruritus. By general treatment measures such as emollients and soothing baths. Topical corticosteroids (medium- to high-potency) or even systemic steroids may be needed to abate the eruption (46). Use of high-potency topical steroids over large surface areas can lead to systemic absorption, and, while controversial, may put patients at risk of delivering low-birth-weight infants. Antihistamines with sedative effect can be effective against pruritus and may help patients to sleep better (47).

ERYTHEMA ANNULARE CENTRIFUGUM

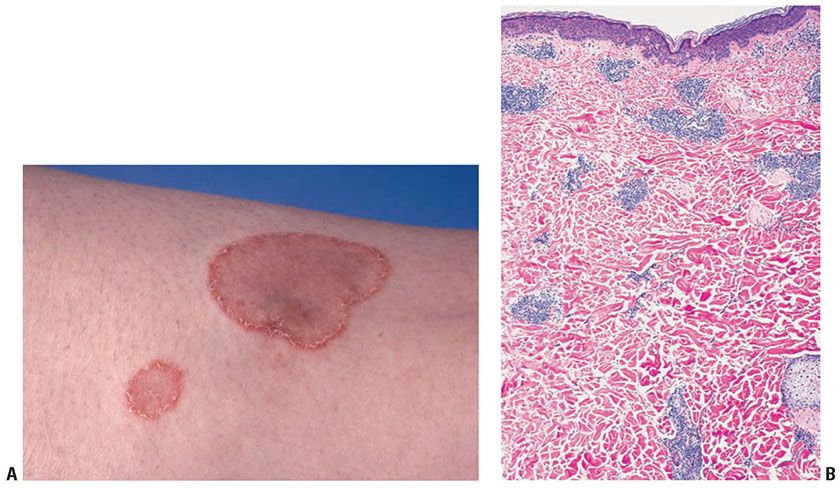

Clinical Summary. Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) is also known as gyrate erythema and represents a hypersensitivity reaction manifesting as arcuate and polycyclic areas of erythema. The condition has been categorized into superficial and deep variants. The deep form was originally described by Darier and is characterized by annular areas of palpable erythema with central clearing and absence of surface changes (48). The superficial variant differs only by the presence of a characteristic trailing scale—a delicate annular rim of scale that trails behind the advancing edge of erythema (49) (Fig. 7-3A). Small vesicles may occur.

Figure 7-3 A: Erythema annulare centrifugum. Characteristic delicate annular rim of scale trailing behind the edge of erythema. (Courtesy of Ronald O. Perelman Department of Dermatology, New York University School of Medicine, New York, New York.) B: Gyrate erythema, deep form. Superficial and deep, dense perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate.

The lesions may attain considerable size (up to 10 cm across) over a period of several weeks, may be mildly pruritic, and have a predilection for the trunk and proximal extremities. Most cases resolve spontaneously within 6 weeks; however, the condition may persist or recur for years. In a study of 66 patients with erythema annulare centrifugum, the lower extremities were the most frequently involved area and the superficial variant was more common than the deep form, 78% versus 22%, respectively (50).

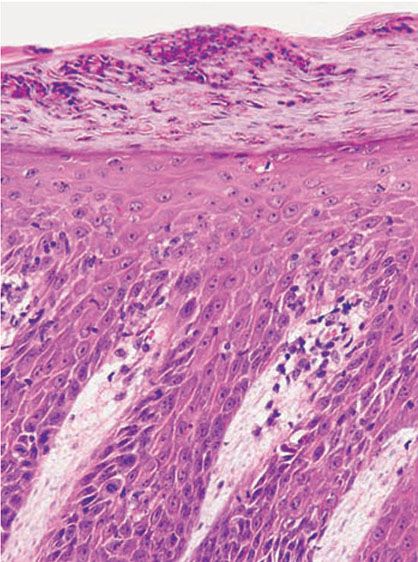

Histopathology. In the superficial variant of gyrate erythema, there is a superficial perivascular tightly cuffed lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with endothelial cell swelling and focal extravasation of erythrocytes in the papillary dermis. In addition, there is focal epidermal spongiosis and parakeratosis (49).

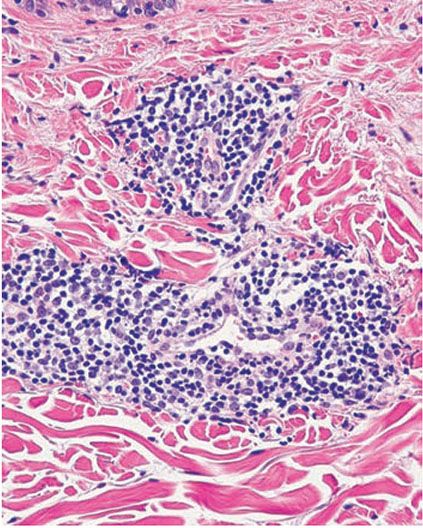

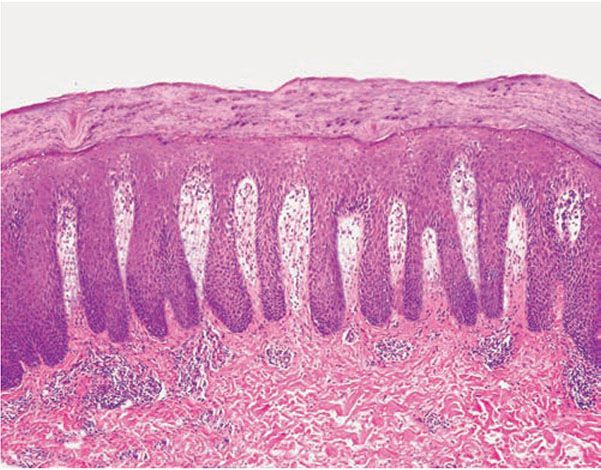

In the classic deep form or indurated type, a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate characterized by a tightly cuffed “coat-sleeve–like” pattern is present in the mid- and deep dermis (Figs. 7-3B and 7-4). Occasionally, focal vacuolar alteration of the basal layer keratinocytes may be noted in the deep variant (51).

Figure 7-4 Gyrate erythema, deep form. Dense perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate.

Pathogenesis. The exact pathogenesis of EAC is not clear. It has been associated with occult infections, dermatophytosis, candidiasis, medications, hormonal changes and, rarely, an underlying malignancy (52–54). Because a patient responded with complete clearance with etanercept, it has been suggested that it may be a tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-dependent process (55).

Differential Diagnosis. The rather striking coat-sleeve–like perivascular arrangement of the infiltrate seen in the deep form of gyrate erythema is encountered also in secondary syphilis. However, in secondary syphilis numerous plasma cells and histiocytes are usually present, and the endothelial cells are swollen. The presence of increased deposits of connective tissue mucin distinguishes tumid lupus erythematosus from deep gyrate erythema.

Principles of Management. EAC is usually a self-limited process and may not require any treatment. Topical and systemic steroids, calcipotriol, metronidazole, and etanercept have been reported to show some efficacy in the resolution of the lesions (55,56). Treatment of any underlying disorder, if identifiable, is indicated.

ERYTHEMA GYRATUM REPENS

Clinical Summary. Erythema gyratum repens (EGR) is a very rare but clinically highly characteristic dermatosis that was originally reported in 1952 by Gammel (57). It mostly represents a paraneoplastic syndrome that is associated with an internal malignancy in 82% of patients (58). The most common associated malignancies include lung/bronchial, esophageal, and breast carcinomas. Occurrence of EGR as a nonparaneoplastic phenomenon has also been described (59,60). The eruption typically is very pruritic and is composed of concentric and parallel bands of erythema and scale, producing a “wood-grain” pattern on the skin. The trunk and extremities are preferentially involved; however, the entire integument may be affected. The rash of EGR constantly migrates at a fairly rapid rate (up to 1 cm/day). Ichthyosis and palmar/plantar hyperkeratosis have been observed concomitantly in 16% and 10% of patients, respectively (61).

Histopathology. The histologic picture usually shows mild acanthosis, spongiosis, focal parakeratosis, and a superficial perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate that may also include eosinophils, neutrophils, and melanophages (61,62).

Pathogenesis. Several authors have described granular deposition of C3, C4, or IgG at the basement membrane zone on direct immunofluorescence, suggesting that EGR may have an immunologic basis (63,64). In particular, Caux et al. (64), using immunoelectron microscopy, noted that the deposits are located in the sublamina densa region.

Differential Diagnosis. Clinical differential diagnosis of these peculiar polycyclic lesions includes unusual forms of tinea corporis, urticaria, necrolytic migratory erythema, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and atypical cases of bullous pemphigoid or linear IgA (65). Histopathologically in EGR there is absence of PAS-positive hyphae in the cornified layer and no marked dermal edema, necrotic keratinocytes, interface dermatitis, or subepidermal blistering. Patients presenting with lesions suspicious of EGR should be evaluated for the detection of underlying malignancy.

Principles of Management. The condition is known to remit with treatment and eradication of the associated malignancy (61). Antihistamines and topical or systemic corticosteroids have been reported to be beneficial in some cases (66,67).

ERYTHEMA DYSCHROMICUM PERSTANS

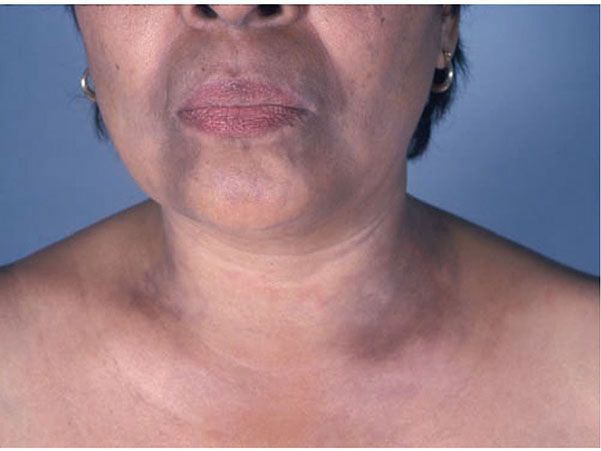

Clinical Summary. Erythema dyschromicum perstans (EDP), also called ashy dermatosis, was first described by Oswaldo Ramirez in 1957 (68). It is an asymptomatic eruption that begins with disseminated macules showing an elevated red active border, which by peripheral extension and coalescence form large patches with a polycyclic outline (Fig. 7-5). Although the macules may at first be erythematous before assuming their characteristic bluish gray color, they often appear blue-gray from the very beginning. The disease progresses slowly, and the discoloration persists. The most common areas of involvement are the trunk, arms, and face. Most patients with this disorder are Latin Americans (69). However, it has been observed in Asians (70) and other ethnic backgrounds (71). A genetic susceptibility to develop the disease in Mexican mestizo patients has been associated with the HLA-DR4 DRB1(*)0407 allele (72).

Figure 7-5 Erythema dyschromicum perstans. Disseminated blue-gray macules on face, neck, and chest. (Courtesy of Ronald O. Perelman Department of Dermatology, New York University School of Medicine, New York, New York.)

Histopathology. In the early active stage or in the erythematous active border, there is vacuolar alteration of the basal layer. The papillary dermis shows a mild to moderate perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes intermingled with melanophages (73). There may also be exocytosis of lymphocytes into the basal layer, and occasional necrotic keratinocytes or colloid bodies resembling those seen in lichen planus may be present. Late lesions show aggregates of melanophages in the papillary dermis (73).

Pathogenesis. Electron microscopic examination reveals many vacuoles delimited by a membrane within the affected keratinocytes as the ultrastructural counterpart of the vacuolar alteration. This is associated with widening of the intercellular spaces and retraction of desmosomes to either one cell or the other. Additional findings include discontinuities in the subepidermal basement membrane and the presence in the dermis of melanophages containing aggregates of melanosomes enclosed by a lysosomal membrane (74). It can be assumed that the vacuolar alteration of basal keratinocytes is the cause of the pigmentary incontinence and of the formation of the colloid bodies.

Direct immunofluorescence studies have shown IgG deposition on necrotic keratinocytes at the dermal–epidermal junction. Immunohistochemical studies have revealed that in early lesions, the dermal inflammatory infiltrate is composed primarily of T lymphocytes, both CD4+ (helper-inducer) and CD8+ (cytotoxic-suppressor) subtypes (75). Some authors have found predominance of CD8+ lymphocytes in the inflammatory dermal infiltrate (76).

It has been shown that the expression of ICAM-1 and HLA-DR on basal layer keratinocytes is increased (76,77). The activation molecule AIM/CD69 and the cytotoxic cell marker CD94 have been seen to be expressed in the inflammatory cell infiltrate (77).

Differential Diagnosis. Hyperpigmented disorders included in the differential diagnosis are lichen planus pigmentosus, occupational dermatosis with hyperpigmentation, and drug reactions (71).

EDP may show similarities with interface drug reactions, including the late stage of fixed-drug eruption. Damage and necrosis of the basal keratinocytes resulting in formation of colloid bodies and pigmentary incontinence suggests a possible relationship of EDP to lichen planus pigmentosus, also called lichen planus actinicus or subtropicus (78). However, lichen planus pigmentosus shows a different clinical presentation, characterized by dark brown macules located predominantly on exposed areas and flexural folds and is associated with pruritus. Histologically, it shows a more pronounced lichenoid distribution of the infiltrate and some effacement of rete ridges resulting in epidermal atrophy (73,79).

Principles of Management. Reported therapeutic options for ashy dermatosis are clofazimine, dapsone, chemical peels, antibiotics, corticosteroids, vitamins, tetracyclines, antihistamines, griseofulvin, isoniazid, chloroquine, and psychotherapy. However, none produce satisfactory results (80,81). As with other forms of skin darkening patients may benefit from photoprotection.

PRURIGO SIMPLEX

Clinical Summary. Prurigo is a condition characterized by intensely pruritic, erythematous urticarial papules that are seen in symmetric distribution, especially on the trunk and extensor surfaces of the extremities. Based on its duration it has been divided into acute, subacute, and chronic forms (82). Acute prurigo occurs principally in young children and secondary excoriational changes can be frequently found. Subacute prurigo also known as prurigo simplex subacuta or urticaria papulosa chronica perstans affects more often middle-aged patients, especially women (83). Some patients may have an atopic background or may exhibit dermographism (83). Chronic prurigo or prurigo nodularis is discussed later in this chapter.

Histopathology. Early papules show mild acanthosis, spongiosis with an occasional small spongiotic vesicle, and parakeratosis. The upper dermis contains a mild lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate in a largely perivascular arrangement. An admixture of eosinophils is present in some cases (82,84). Excoriated papules show partial absence of the epidermis, and they are covered with a crust containing degenerated nuclei of inflammatory cells. On serial sectioning, most of the histologic changes may be found to be located around hair follicles, which then show spongiosis and exocytosis of lymphocytes in the follicular infundibulum, and a perifollicular infiltrate (85). In other instances, there is distinct sparing of the follicular structures (84). Immunohistochemical studies have shown that the inflammatory infiltrate in subacute prurigo is composed mainly of T lymphocytes, with a predominance of CD8+ cells, CD15+ neutrophils and CD68+ macrophages (86).

Pathogenesis. The exact etiology in most cases of prurigo is unknown. Both peripheral and central nervous mechanisms have been suggested to be involved in the perception of intense pruritus (87). Acute prurigo may be caused by toxic substances deposited in the skin by insect stings or bites, and affected patients may have associated atopic eczema (83). While most of the subacute and chronic forms of prurigo appear to be idiopathic, psychogenic, or emotional factors are commonly present (87). There is some evidence that TH2 cells play a pathogenic role in subacute prurigo (88).

Differential Diagnosis. Dermatitis herpetiformis, scabies, transient acantholytic dermatoses (Grover disease), Darier disease, and papular urticaria may resemble prurigo simplex in clinical appearance. Dermatitis herpetiformis can be differentiated clinically because there is no grouping of lesions and histologically there is absence of neutrophilic microabscesses at the tips of dermal papillae and of neutrophils, eosinophils, and nuclear dust in the dermal infiltrate. A negative direct immunofluorescence study of perilesional skin will help to exclude dermatitis herpetiformis or urticarial bullous pemphigoid (83). The histologic picture of prurigo simplex resembles that of a subacute eczematous dermatitis, except that the extent of its papular lesions is much more limited. The presence of Sarcoptes scabiei mites within the cornified layer will be diagnostic of scabies. Acantholytic dyskeratosis will support Darier or Grover disease. Histologic differentiation from papular urticaria is not always possible.

Principles of Management. The inflammation and severe itching in acute prurigo can be successfully treated with topical steroids and antihistamines. Due to the relapsing course of subacute prurigo, treatment is required when exacerbations occur. More potent topical steroids, calcipotriol, capsaicine, topical cyclosporine, and lidocaine may be useful in more persistent lesions. Bath-photochemotherapy, including PUVA, medium-dose ultraviolet A1 (MD-UVA1) and narrow-band ultraviolet B (NB-UVB), has been reported to be an effective and safe treatment option (89).

PRURIGO NODULARIS

Clinical Summary. Prurigo nodularis is a chronic dermatitis characterized by raised, firm hyperkeratotic or excoriated papulonodules, usually from 5 to 12 mm in diameter but occasionally larger. They occur chiefly on the extensor surfaces of the extremities and are intensely pruritic (90). The disease usually begins in middle age, and women are more frequently affected than men (91). Prurigo nodularis may coexist with lesions of lichen simplex chronicus, and there may be transitional lesions (90).

The exact cause is unknown, but local trauma, insect bites, atopic background, and infectious, metabolic or systemic diseases have been implicated as predisposing factors in some cases (90,92–96). A recent study demonstrated that in up to 87% of the patients with prurigo nodularis, an underlying disease could be established (97). A recent psychometric study has shown that psychological factors such as anxiety and depression in patients with prurigo nodularis were more severe than in the control group (98).

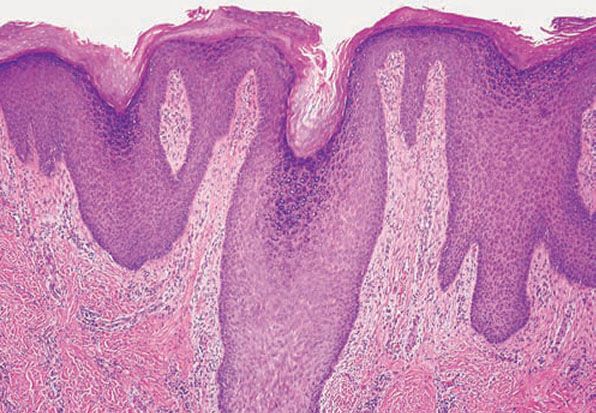

Histopathology. One observes pronounced orthohyperkeratosis with focal parakeratosis, hypergranulosis, and irregular acanthosis (99). In addition, there may be papillomatosis and irregular downward proliferation of the epidermis and adnexal epithelium (100) approaching pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (101) (Fig. 7-6). The papillary dermis shows vertically oriented collagen bundles with increased numbers of fibroblasts and capillaries and a perivascular inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes and to a lesser extent eosinophils and neutrophils (99). Occasionally, prominent neural hyperplasia may be observed (101); however, this is an uncommon finding and is not considered to be an essential feature for the diagnosis of prurigo nodularis (99,102). Eosinophils and marked eosinophil degranulation may be seen more frequently in patients with an atopic background (92). Dermal Langerhans cells are shown to be increased in prurigo nodularis compared to normal controls (103). The identification of enlarged dendritic mast cells containing fewer cytoplasmic granules within the lesional dermis has recently been described (104).

Figure 7-6 Prurigo nodularis. Marked irregular acanthosis, focal hypergranulosis, and compact orthokeratosis with parakeratosis.

Pathogenesis. It is generally assumed that the neural proliferation in prurigo nodularis is a secondary phenomenon due to chronic trauma by scratching. Still, it may be that the extreme pruritus is related to the increased number of dermal nerves (101). A recent study showed that nerve growth factor (NGF) and its receptors are overexpressed in lesional skin of prurigo nodularis compared to normal controls, with the inflammatory cell infiltrate being the source of NGF with resulting neural hyperplasia (105). Calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P are markedly increased in lesions of prurigo nodularis compared to normal skin. These neuropeptides may mediate the pruritus in prurigo nodularis (106). These findings correlate with an increased density of substance P-positive nerve fibers in prurigo nodularis lesions (107). On electron microscopic examination, it is evident that the neural proliferation involves both axons and Schwann cells (101). Many nerve fibers are also demonstrable with immunostains for S100 protein (108), neurofilament, and myelin basic protein (109). Immunohistochemical analysis has confirmed that they are mostly sensory nerves by demonstrating the presence of sensory neuropeptides (110). In addition, Merkel cells are reported to be increased in number in the basal cell layer of the affected interfollicular epidermis, suggesting that these specialized sensory receptors interacting with the neural fibers may participate in the pathogenesis of the disease (111). The evidence of reduced intraepidermal nerve fiber density in lesional and nonlesional prurigo nodularis skin suggests the presence of subclinical cutaneous neuropathy (112).

Differential Diagnosis. Lichen simplex chronicus may have a similar histologic picture, although less exuberant and less circumscribed (99,102). Multiple keratoacanthomas, which often show less of a central crater than solitary keratoacanthomas, may be difficult to distinguish from prurigo nodularis because both show marked epidermal and epithelial hyperplasia.

Principles of Management. Prurigo nodularis may have a great impact on patients’ quality of life. Unfortunately, available treatments have shown mild to moderate efficacy (113). Oral and intralesional steroids can be used to reduce inflammation. Occlusive dressings containing potent topical steroids may enhance the efficacy of the treatment, preventing scratching (114). There have been some case reports on the use of topical immunomodulators, tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, for steroid-unresponsive patients (115). Phototherapy (UVA with or without psoralens and UVB) has proven to be an efficacious and safe treatment option (89,116). Thalidomide has been used with good results in patients with prurigo nodularis refractory to other treatments. However, side effects, such as peripheral neuropathy and sedation, may lead to discontinuation of the treatment (117). Antihistamines, anxiolytics, and more recently gabapentin (118), pregabalin (119), opiate receptor antagonists (120), lenalidomide (121), and the neurokinin receptor 1 antagonist, aprepitant (122), have been reported to be useful in the treatment of prurigo nodularis.

PSORIASIS

Psoriasis may be divided into psoriasis vulgaris, generalized pustular psoriasis, and localized pustular psoriasis.

Psoriasis Vulgaris

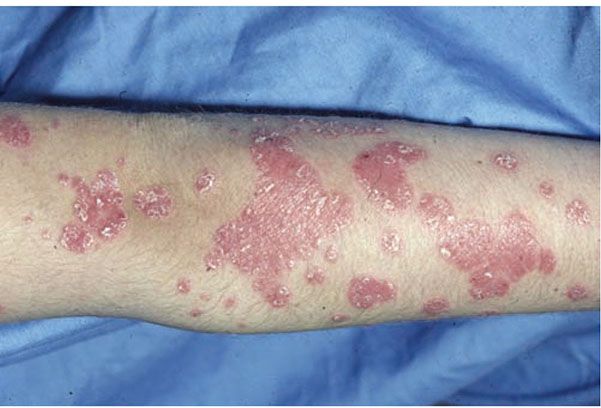

Clinical Summary. Psoriasis vulgaris is a common chronic inflammatory skin disorder that affects approximately 1.5% to 2% of the population in the Western countries. It is characterized by pink to red scaly papules and plaques (Fig. 7-7). The lesions are of variable size, sharply demarcated, dry, and usually covered with layers of fine, silvery scales. As the scales are removed by gentle scraping, fine bleeding points are usually seen—the so-called Auspitz sign. The scalp, sacral region, and extensor surfaces of the extremities are commonly involved, although in some patients the flexural and intertriginous areas are mainly affected (inverse psoriasis). An acute variant—guttate or eruptive psoriasis—is often seen in younger patients and is characterized by an abrupt eruption of small lesions associated with acute group A β-hemolytic streptococcal infections (123). Involvement of the nails is common; the most frequent alteration of the nail plate surface is the presence of pits (124). In severe cases, the disease may affect the entire skin and present as generalized erythroderma. Pustules are generally absent in psoriasis vulgaris, although pustules on palms and soles occasionally occur. Rarely, one or a few areas show pustules, and this is referred to as “psoriasis with pustules.” Also rarely, severe psoriasis vulgaris develops into generalized pustular psoriasis. Oral lesions such as stomatitis areata migrans (geographic stomatitis) and benign migratory glossitis (geographic tongue) may be seen in psoriasis vulgaris as well as in generalized pustular psoriasis (125,126).

Figure 7-7 Psoriasis vulgaris. Sharply demarcated erythematous scaly papules and plaques on the upper extremity. (Courtesy of Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.)

Generalized Pustular Psoriasis

Clinical Summary. Generalized pustular psoriasis includes (a) acute generalized pustular psoriasis (von Zumbusch type and acute exanthematous type), (b) generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (impetigo herpetiformis), (c) infantile and juvenile pustular psoriasis, and (d) subacute annular or circinate pustular psoriasis (127).

This cutaneous eruption is characterized by the presence of variable numbers of sterile pustules appearing in erythematous and scaly lesions associated with moderate to severe constitutional symptoms (128). Several exacerbations may occur, and lesions of ordinary psoriasis may be seen in the intervals between them.

The four variants of generalized pustular psoriasis show considerable resemblance and overlapping in their clinical picture and also have a similar histologic appearance. They differ mainly in the mode of onset and the distribution of the lesions. Frequently, all four diseases show oral pustules, particularly on the tongue (129).

Acute generalized pustular psoriasis of von Zumbusch is generally diagnosed when the pustular eruption occurs in patients with preexisting psoriasis, either of the plaque type (130) or of the erythrodermic type (131). Frequently, the eruption occurs after systemic steroid therapy withdrawal (127,132). The exanthematous type of generalized pustular psoriasis refers to a group of patients with later onset of psoriasis, atypical distribution of the lesions, and a rapid and apparently spontaneous pustular eruption (133).

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy is a rare pustular eruption that appears during the last trimester of pregnancy. It starts with flexural lesions of psoriasis followed by a generalized pustular eruption. It may occur repeatedly during successive pregnancies (134). Some authors have considered it to be the same disease as impetigo herpetiformis (127), but others claim that they stand as separate entities (135,136).

In some instances of subacute annular pustular psoriasis, the annular or gyrate lesions show a clinical resemblance to subcorneal pustular dermatosis (137,138). Figurate lesions are more frequently seen in subacute or chronic forms of generalized pustular psoriasis (127). Annular pustular psoriasis, although usually generalized, in some instances may be localized (139).

Very rarely, children develop generalized pustular psoriasis, also known as infantile and juvenile pustular psoriasis. In these patients the disease has a benign course with frequent spontaneous remissions (140).

Localized Pustular Psoriasis

Clinical Summary. There are three types of localized pustular psoriasis: (a) “psoriasis with pustules” (132,133), in which only one or a few areas of psoriasis show pustules and the tendency to change into a generalized pustular psoriasis is low; (b) localized acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau, which occasionally evolves into generalized acrodermatitis continua; and (c) pustular psoriasis of the palms and soles, with two variants: the chronic palmoplantar pustulosis, also called pustulosis palmaris et plantaris, and the acute palmoplantar pustulosis, or “pustular bacterid.” Both are occasionally seen in association with psoriasis vulgaris (127). The relationship of reactive arthritis (Reiter disease) to psoriasis is discussed in the description of this condition.

Acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau is the term used when the pustular eruption involves the distal portions of the hands and feet. In the localized type of acrodermatitis continua, these are the only areas affected, whereas in the generalized type of acrodermatitis continua, extensive areas of the skin in addition to the acral portions of extremities are involved (133). Atrophy of the skin and permanent nail loss may occur on the fingers and toes.

Pustulosis palmaris et plantaris is a chronic, relapsing disorder occurring on the palms, soles, or both (Fig. 7-8). Crops of small, deep-seated pustules are seen within areas of erythema and scaling. In the earliest stage, the lesions may appear as vesicles or vesiculopustules. During the subsiding stage, the pustules appear as brown macules. The sites of predilection are the midpalms and thenar eminences of the hands and the heels and insteps of the feet (141). In pustulosis palmaris et plantaris, in contrast to acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau, the acral portions of the fingers and toes are spared. An acute variant called “pustular bacterid” (142) describes a rare eruption of large and sterile pustules on hands and feet.

Figure 7-8 Pustular psoriasis (palmar pustulosis). Confluent pustules on erythematous scaly skin of the palm. (Courtesy of Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.)

Psoriasis and AIDS

Clinical Summary. The association between psoriasis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is commonly seen. The prevalence of psoriasis is reported to be 1.3% to 2.5% in HIV-positive patients (143,144). Clinically, psoriasis may have a more severe course with sudden exacerbations and may be refractory to treatment (143,145). Extensive erythrodermic psoriasis may occur (146). Palmoplantar involvement, flexural (inverse) psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis were found to be more frequent in patients who developed psoriasis after HIV infection (144). Although a direct relation between the stage of HIV infection and the severity of psoriasis has not been found, a trend of low peripheral T-cell CD4+ (helper-inducer) counts and a more severe clinical course have been noted (144).

Extracutaneous Manifestations of Psoriasis

Beyond cutaneous involvement, patients with psoriasis often suffer from other medical comorbidities. Approximately 20% to 35% of patients have psoriatic arthritis, an inflammatory arthritis that characteristically involves the terminal interphalangeal joints, but also frequently affecting the large joints, so that a clinical differentiation from rheumatoid arthritis is often difficult (however, the rheumatoid factor is generally absent) (147). Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory condition and can lead to premature atherogenic inflammation and advanced vascular aging and markedly increased cardiovascular risks. Patients with psoriasis have been found to have higher rates of the metabolic syndrome and obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, depression, lymphoma, and inflammatory bowel disease than the general population (148). Like psoriasis, these comorbid conditions may all harbor an increased expression of inflammatory cytokine mediators at the root of their pathogenesis.

Histopathology of Psoriasis Vulgaris

The histologic picture of psoriasis vulgaris varies considerably with the stage of the lesion and usually is diagnostic only in early, scaling papules and near the margin of advancing plaques.

The earliest pinhead-sized macules or smooth-surfaced papules show subtle histologic changes with a preponderance of dermal changes (149,150). At first, there is capillary dilation and edema in the papillary dermis, with a lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding the capillaries. The lymphocytes extend to the lower portion of the epidermis, where slight spongiosis develops. Then focal changes occur in the upper portion of the epidermis, where granular cells become vacuolated and disappear, and mounds of parakeratosis are formed. Neutrophils are usually seen only at the summits of some of the mounds of parakeratosis and appear scattered through an otherwise orthokeratotic cornified layer (Fig. 7-9). These mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils represent the earliest manifestation of Munro microabscesses (150). At this stage, which is characterized clinically by an early scaling papule, a histologic diagnosis of psoriasis can often be made. In some cases, when there is marked exocytosis of neutrophils, they may aggregate in the uppermost portion of the spinous layer to form small spongiform pustules of Kogoj. Lymphocytes remain confined to the lower epidermis, which, as more and more mitoses occur, becomes increasingly hyperplastic. The epidermal changes are at first focal, but later become confluent, leading clinically to plaques.

Figure 7-9 Early psoriasis. Mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils, thin granular layer, moderate acanthosis, focal spongiosis, increased mitotic figures, dilated blood vessels at the tip of the dermal papillae, and perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and a few neutrophils.

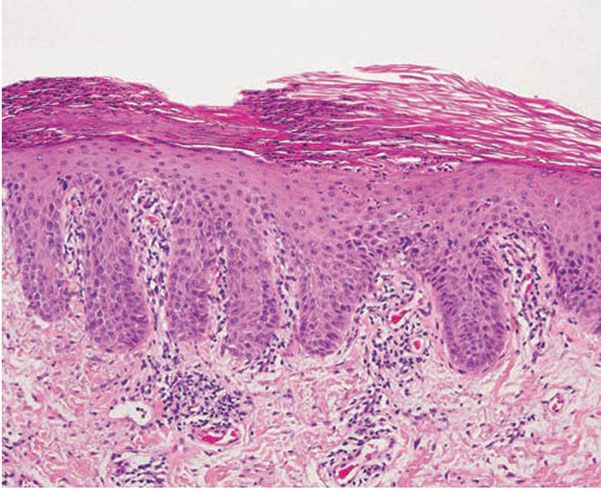

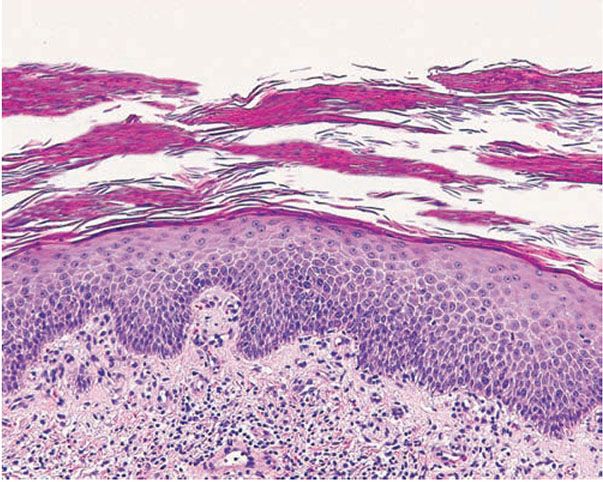

In the fully developed lesions of psoriasis, as best seen at the margin of enlarging plaques, the histologic picture is characterized by (a) acanthosis with regular elongation of the rete ridges with thickening in their lower portion; (b) thinning of the suprapapillary epidermis with the occasional presence of small spongiform pustules; (c) pallor of the upper layers of the epidermis; (d) diminished to absent granular layer; (e) confluent parakeratosis; (f) the presence of Munro microabscesses; (g) elongation and edema of the dermal papillae; and (h) dilated and tortuous capillaries (Fig. 7-10).

Figure 7-10 Psoriasis, well-developed plaque. Markedly elongated rete ridges, absent granular layer, parakeratosis with neutrophils, and dilated tortuous vessels in the dermal papillae.

Of the listed features, only the spongiform pustules of Kogoj and Munro microabscesses are truly diagnostic of psoriasis, and, in their absence, the diagnosis can rarely be made with certainty on a histologic basis. The changes in active psoriasis are discussed in detail later.

The rete ridges show considerable elongation and extend downward to a uniform level, resulting in regular acanthosis (Fig. 7-11). They are often slender in their upper portion but show thickening (“clubbing”) in their lower portion. Not infrequently, adjacent rete ridges seem to coalesce at their bases due to tangential sectioning. Usually, intercellular and intracellular edema is absent in the rete ridges, and keratinocytes located well above the basal layer show deep basophilia. In addition, mitoses are not limited to the basal layer as in normal skin but are also seen above the basal layer. This, together with a considerable lengthening of the basal cell layer due to elongation of the rete ridges, results in a marked increase in the number of mitoses. This increase has been calculated to be 27 times the number of mitoses in uninvolved skin (151).

Figure 7-11 Psoriasis, well-developed plaque. Acanthosis with club-shaped rete ridges of even length, suprabasal mitoses, thin suprapapillary epidermal plates, absent granular layer, pallor of the upper epidermis, and confluent parakeratosis with collections of neutrophils.

The suprapapillary epidermis appears relatively thin in comparison with the markedly elongated rete ridges, and the cells in the upper layers of the epidermis may appear enlarged and pale stained as a result of intracellular edema and hypogranulosis. Keratinocytes beneath the parakeratotic cornified layer may be intermingled with neutrophils (152). The histologic picture is then that of a small spongiform pustule of Kogoj (Fig. 7-12). Although it is only a micropustule, it is nevertheless of the same type as the much larger macropustules seen in pustular psoriasis. Such a spongiform pustule, highly diagnostic for psoriasis and its variants, shows aggregates of neutrophils within the interstices of a spongelike network formed by degenerated and thinned epidermal cells (153).

Figure 7-12 Psoriasis. Closer view of a spongiform pustule of Kogoj formed by collections of neutrophils in the spinous and granular layers.

In some instances the cornified layer consists entirely of confluent parakeratosis forming a platelike scale with a concomitant absence or diminution of the granular layer. However, occasional focal orthokeratosis with preservation of the underlying granular cells is present.

Munro microabscesses are located within the parakeratotic areas of the cornified layer (Fig. 7-13). They consist of accumulations of neutrophils and pyknotic nuclei of neutrophils that have migrated there from capillaries in the papillae through the suprapapillary epidermis. As a rule, Munro microabscesses are easily found in early lesions but are few in number or absent in longstanding lesions (154).

Figure 7-13 Psoriasis, plaque lesion. Closer view of the neutrophilic collections within the parakeratotic cornified layer (Munro microabscess). Note the thin suprapapillary epidermal plates and dilated blood vessels in the dermal papillae.

The dermal papillae, in accordance with the elongation and basal thickening of the rete ridges, are elongated and club shaped. They show edema, and the capillaries within them appear dilated and tortuous. A relatively mild inflammatory infiltrate is present in the upper dermis and the papillae. It consists of lymphocytes, except in early lesions, in which neutrophils are also present in the upper portion of the papillae (155).

An entirely typical histologic picture as described earlier is not always found, even if the biopsy specimens are taken from clinically typical lesions of psoriasis (156). Orthokeratosis often appears intermingled with parakeratosis. In such cases, one may see vertically adjoining areas of orthokeratosis and parakeratosis, focal parakeratosis, or, occasionally, alternating layers of orthokeratosis and parakeratosis. The last-named pattern indicates a fluctuation in the activity of the psoriasis.

The bleeding points that may be produced by gentle scraping of the skin (Auspitz sign) correspond to the tips of dermal papillae. They are attributable to the following histologic changes: parakeratosis, intracellular edema of keratinocytes in the suprapapillary epidermis, thinning of the suprapapillary plates, and dilation of the capillaries in the upper portion of the papillae.

Guttate or eruptive psoriasis shows the histologic features of an early or active lesion of psoriasis, where there is more pronounced inflammatory infiltrate and less acanthosis as compared with a well-developed chronic plaque of psoriasis. Because of its acute onset, one may observe the remaining normal basket-weave orthokeratotic cornified layer overlying the mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils, which, in turn, may appear loosely arranged (Fig. 7-14).

Figure 7-14 Eruptive psoriasis. Multilayered mounds of parakeratosis admixed with basket-weave orthokeratosis, slight acanthosis, and dilated blood vessels in the dermal papillae.

The histologic picture of erythrodermic psoriasis in some instances shows enough of the characteristics of psoriasis to allow this diagnosis. Frequently, however, the histologic appearance is indistinguishable from that of a chronic eczematous dermatitis (157).

Histopathology of Generalized Pustular Psoriasis

Whereas in ordinary psoriasis the spongiform pustule of Kogoj is a very small micropustule and is seen only in early, active lesions, it occurs as a macropustule in all variants of generalized pustular psoriasis and represents their characteristic histologic lesion. The spongiform pustule forms through the migration of neutrophils from the papillary dermal capillaries to the upper layer of epidermis, where they aggregate within the interstices of a spongelike network formed by degenerated and thinned epidermal cells (153). As the size of the pustule increases, the epidermal cells in the center of the pustule undergo complete cytolysis so that a large single cavity forms (Fig. 7-15). At the periphery of the pustule, however, the network of thinned epidermal cells persists for a much longer time. As the neutrophils of the spongiform pustule move up into the cornified layer, they become pyknotic and assume the appearance of a large Munro abscess (130,158).

Figure 7-15 Pustular psoriasis. Large collections of neutrophils with spongiosis in the upper spinous layer and granular layer.

In addition to the large spongiform pustules, the epidermal changes in generalized pustular psoriasis are very much like those seen in psoriasis vulgaris, consisting of parakeratosis and elongation of the rete ridges. The upper dermis contains an infiltrate of lymphocytes, and neutrophils can often be seen migrating from the capillaries in the papillae into the epidermis (159). The oral lesions show the same spongiform pustule formation as those seen on the skin (129).

In the healing stage, the lesions of all types of generalized pustular psoriasis may present the same histologic appearance as ordinary psoriasis (130).

Histopathology of Localized Pustular Psoriasis

In the variants of localized pustular psoriasis “psoriasis with pustules” (132,133) and localized annular pustular psoriasis, the histologic picture is the same as that described for generalized pustular psoriasis.

In localized acrodermatitis continua of Hallopeau, the nail bed is mainly affected, showing marked epithelial hyperplasia with variable numbers of spongiform pustules, hypogranulosis, and hyperkeratosis with mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils. The nail matrix is only occasionally involved (160).

In pustulosis palmaris et plantaris there is a fully developed large intraepidermal unilocular pustule. It is elevated only slightly above the surface but presses onto the underlying dermis. Many neutrophils are present within the cavity of the pustule. The epidermis surrounding the pustule shows slight acanthosis, and an inflammatory infiltrate can be seen beneath the pustule (161). In many instances one can observe typical, although small, spongiform pustules in the epidermal wall of the pustule, most commonly at the junction of the lateral walls and the overlying epidermis (161–165). These spongiform pustules are identical to those seen in the walls of the pustules of generalized pustular psoriasis.

Very early lesions may show spongiosis and exocytosis of lymphocytes in the lower epidermis overlying the tips of dermal papillae (164). This may be followed by the formation of a small intraepidermal vesicle containing mostly lymphocytes (161,164). Subsequently, there is a massive exocytosis of neutrophils, which penetrate the intercellular spaces of the vesicle wall, where the histologic picture of spongiform pustules is then seen (161). In the acute form, pustular bacterid, leukocytoclastic vasculitis has been described (166).

Histopathology of Psoriasis and AIDS

The histologic picture in most cases is similar to that of psoriasis. In others, the histologic sections may show acanthosis without thinning of the suprapapillary epidermis, slight spongiosis, rare necrotic keratinocytes, and a superficial perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes that occasionally contains some plasma cells (167). As in other dermatitides related to AIDS, eosinophils may be present in the inflammatory infiltrate.

Pathogenesis of Psoriasis Vulgaris

Although the cause of psoriasis is unknown, there is increasing evidence of a complex interaction among altered keratinocytic proliferation and differentiation, inflammation, and immune dysregulation.

Electron Microscopy

The earliest recognizable morphologic events in psoriasis have been investigated in lesions that cleared with corticosteroid under occlusion and then were allowed to relapse. The earliest indications of relapse, as seen by electron microscopy, are swelling and intercellular widening of endothelial cells. This is followed by the appearance around postcapillary venules of mast cells showing degranulation. Hours later, activated macrophages migrate into the lower epidermis, where there is loss of desmosome–tonofilament complexes. Only then are lymphocytes and neutrophils seen (168). Ultrastructurally, in well-developed lesions, psoriatic keratinocytes from the suprabasal layers of the epidermis show significant abnormalities. The tonofilaments are decreased in number and in diameter and lack their normal aggregation. The size and number of keratohyaline granules are greatly reduced, and occasionally these are absent (169,170). The cornified cells possess thin tonofilaments and often retain organelles and a nucleus as parakeratotic cells. They often fail to form a marginal band and to lose their outer plasma membrane (171). Basal keratinocytes may show cytoplasmic processes protruding into the dermis through gaps in the basal lamina. These are more numerous in active and untreated lesions and are absent in completely resolved and uninvolved psoriatic skin (172). The intercellular spaces between all epidermal cells are widened because of a deficiency in the glycoprotein-rich cell surface coat, so that intercellular adhesion is limited to the desmosomes (171,173). Electron microscopic studies have confirmed the view that the keratinocytes in psoriasis are defective and not just immature owing to accelerated epidermal proliferation. Although a correlation exists in psoriasis between an increased rate of mitosis and parakeratosis, rapid proliferation of the epidermis does not cause parakeratosis (174).

Ultrastructural studies of the spongiform pustule of Kogoj, one of the most characteristic histologic structures encountered in psoriasis, reveal that it is located in the uppermost portion of the spinous and granular layers, where neutrophils lie intercellularly in a multilocular pustule in which the spongelike network is composed of degenerated and flattened keratinocytes (153).

The ultrastructure of the capillary loops in the dermal papillae shows them to be different from normal capillary loops. In psoriasis, the capillaries show a wider lumen, bridged fenestrations and gaps between endothelial cells, edematous areas in the cytoplasm of endothelial cells, pericytes and myocytes, extravasation of red blood cells and inflammatory cells, and a thickened multilayered basement membrane (175). This finding may be a result of the deposition of amorphous substances and accumulation of collagen fibrils in the basement membrane zone (176).

Epidermal Cell Cycle Kinetics

The rate of epidermal cell replication is markedly accelerated in active lesions of psoriasis, as shown by the higher than normal number of basal and suprabasal mitotic figures and the greater number of premitotic cells labeled by tritiated thymidine (177). The mitotic activity within different lesions of psoriasis and even within the same lesion can vary considerably and seems to be correlated with the degree of parakeratosis. Thus, psoriatic epidermis with 91% to 100% parakeratosis shows on average five times as many mitotic figures as psoriatic epidermis with only 0% to 20% parakeratosis (156). The frequent finding in psoriasis of alternating layers of orthokeratosis and parakeratosis suggests that epidermal growth activity fluctuates in the lesions (156). Step sections of early “punctate” papules show a mitotically very active parakeratotic center surrounded by a zone of a thickened granular layer with a relatively low mitotic rate (178).

Early calculations made it appear likely that in psoriatic lesions there was a great acceleration of the transit time of cells from the basal cell layer to the uppermost row of the squamous cell layer, from approximately 53 days in normal epidermis to only 7 days in the epidermis of active psoriatic lesions (177).

Further investigations (179) have found that (a) the germinative cell cycle is shortened from 311 to 36 hours, indicating that psoriatic keratinocytes proliferate approximately eightfold faster than do normal keratinocytes, (b) there is a doubling of the proliferative cell population in psoriasis from 27,000 to 52,000 cells/mm2 of epidermal surface area, and (c) 100% of the germinative cells of the epidermis enter the growth fraction instead of only 60% for normal subjects. However, in another study (180), it was shown that the germinative cell cycle time is around 200 hours in normal epidermis and about 100 hours in psoriatic epidermis, a twofold rather than an eightfold acceleration.

The source of the cycling cells in the suprabasal layers of the epidermis is not well defined. They could be an expanded population of basal keratinocytes or could be recruited from the transient-amplifying cells (TAC)—suprabasal keratinocytes committed to terminal differentiation—that might undergo rounds of amplifying divisions above the basal layer (181). Based on keratin studies, it is believed that proliferating keratinocytes may result from recruitment of TAC (181) because they express K1/K10 and predominantly K6/K16 keratins and not K5/K14 as basal keratinocytes do (182).

Recent studies suggested that psoriatic epidermis shows aberrant expression of apoptosis-related molecules representing suppressed apoptotic process, which might be related to proliferative characteristic of the epidermis in this disease (183).

Keratinocyte Differentiation

Keratinocytes undergo the process of differentiation as they migrate upward through the epidermis from the basal layer to the cornified layer. During this process, different structural proteins are synthesized. One such protein family is the keratins, which are intermediate filaments found in the cytoplasm of all epithelial cells. Studies revealed that the keratin pair K5/K14 is expressed in basal keratinocytes (184) and keratins K1/K10 are found in the suprabasal layers. Involucrin, one of the major precursor proteins of the cornified cell envelope, is detected higher in the granular and cornified layers (185). In psoriatic skin, basal keratinocytes continue to express K5/K14; however, keratins K1/K10 are replaced by the so-called hyperproliferation-associated keratins K6 and K16. In addition, involucrin is expressed prematurely in the lower suprabasal layers (182,186). Keratin 17, normally expressed in the deep outer root sheath of the hair follicle, has been found also in the upper suprabasal keratinocytes within the interfollicular psoriatic epidermis (182).

Immunopathology

Immunologic factors play a very important role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Psoriasis is now regarded as a T-cell-mediated disorder. It has been shown that both CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes are found in the papillary dermis and the epidermis of the psoriatic lesions. CD8+ T cells seem to be dominant in the epidermis, whereas the CD4+ T lymphocytes are the predominant subset in the dermis. Presence of CD8+ T cells within the epidermis is believed to be a key event in the pathogenesis of psoriasis (187), with up to one third of them expressing the activation markers (188). Recent data suggest that lesions of psoriasis exhibit clonal expansion of epidermal T lymphocytes. Recurrent lesions also show the recruitment of the identical expanded T-cell clones. Nonlesional skin did not show the presence of the same T-cell receptor rearrangements. These findings suggest that a stable antigen-specific pathogenic T-cell response may play a role in disease perpetuation in psoriasis (189–191). The activation of T lymphocytes may be due to bacterial superantigens such as group A β-hemolytic streptococci. It is suggested that amino acid sequences from streptococcal M-protein share sequences with keratin 17, and therefore an epitope on keratin 17 or keratin 6 may be a target for autoreactive lymphocytes in psoriasis (192,193). Group A streptococcal-reactive CD8+ and to a lesser extent CD4+ T cells in psoriatic epidermis may play a role in the pathogenesis of both poststreptococcal guttate psoriasis (194) and chronic plaque psoriasis (195). Activated CD4+ T cells produce a variety of cytokines, including interleukin 2 (IL-2), TNF-α, and γ-interferon (γ-IFN), which is also produced by CD8+ T lymphocytes (196).

Keratinocytes stimulated by TNF-α may produce IL-8, which is a potent T lymphocyte and neutrophil chemoattractant present in increased amounts in psoriatic epidermis. This cytokine may be involved in the formation of Munro microabscesses (197).

TNF-α plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. It not only initiates Langerhans cell migration by downregulating e-cadherin (which mediates attachment between these cells and surrounding keratinocytes) (198), but it also induces NF-κB, leading to cell survival, proliferation, and transcription of antiapoptotic factors and the expression of the pro-angiogenic vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (199). IL-1β and IL-8, in addition to many other chemokines, are induced downstream, further enhancing dendritic cell activation and migration, T-lymphocyte recruitment, and neutrophil recruitment and microabscess formation (200,201).

Recently, work on TNF-α led to the discovery of the central role of the IL-23/IL-17 pathway in the development of psoriasis, demonstrated by the effects of TNF-α blockade on IL-17 signaling and their synergistic influence on inflammatory cytokine production by keratinocytes (202,203). TH17 cells, one of several innate sources of IL-17 in psoriatic lesions, home to the inflamed skin, where they induce chronic inflammation and tissue damage, neutrophil maturation and chemotaxis, TH1 cell chemotaxis, and keratinocyte proliferation and epidermal hyperplasia (204,205). IL-23 contributes to this process by expanding and activating TH17 cells and inducing IL-22 and thus acanthosis of the epidermis (206,207). IL-23 is also able to convert regulatory T cells (Tregs) into IL-17 producers, as well as directly stimulate dendritic cells to present self-peptides and further augment the psoriatic inflammatory cascade (206,207).

Additionally, γ-IFN is believed to play an important role in the initiation of psoriatic lesions as demonstrated by the induction of pinpoint lesions of psoriasis at sites of γ-IFN injection in previously uninvolved skin (208). γ-IFN induces the expression of the ICAM-1 in keratinocytes and endothelial cells. This molecule mediates the adhesion and trafficking of lymphocytes into the epidermis by binding to its ligand lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1) expressed on lymphocyte membranes (197). In addition, γ-IFN-inducible protein (IP-10) is overexpressed by keratinocytes in psoriatic lesional skin (209). IP-10 is detected in epidermis during cellular immune responses and may have chemotactic as well as mitogenic properties. Psoriatic keratinocytes are shown not to be responsive to the growth inhibition effects of γ-IFN, leading to their hyperproliferative state in the disease (210).

Increased expression of p53 and downregulation of Bcl-2, consistent with the dynamics of psoriasis, have been shown (211). In addition, aberrant cytokine expression has been proposed as an underlying cause of psoriasis, with IL-23 being considered as a master regulator cytokine in the pathogenesis of the disease (212).

Pathogenesis of Localized Pustular Psoriasis

A relationship of pustulosis palmaris et plantaris with psoriasis is not generally accepted, although two facts favor a close relationship: the relatively common occurrence of psoriasis in patients with pustulosis palmaris et plantaris, reported in 19% to 48% of patients (213–215), and the common presence of spongiform pustules in the walls of the pustules of pustulosis palmaris et plantaris. In addition, a leukotactic factor identical to that noted in psoriasis has been found in pustulosis palmaris et plantaris (216).

Pathogenesis of Psoriasis and AIDS

There is evidence of the role of both CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocytes and γ-IFN in the pathogenesis of psoriasis in AIDS (167,217). Paradoxically, as T-helper cell counts decline, it appears that psoriatic lesions exacerbate until a preterminal stage, when the dermatitis improves. The latter event is probably a consequence of a decreased local production of γ-IFN due to the increasing number of infected T-helper lymphocytes or a diminished number of dermal lymphocytes available to produce this cytokine (154). However, in a recent study, it was shown that γ-IFN serum levels were much higher in HIV-positive psoriatic patients than HIV-negative subjects (218).

The immunodysregulation resulting from HIV infection may trigger psoriasis in those genetically predisposed by carrying the HLA-Cw*0602 allele. HLA-Cw*0602 could act as a cross-reactive target for cytotoxic T lymphocytes responding to peptides from microorganisms. Human retrovirus 5 has been implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriatic arthropathy but not psoriasis (217). Immunohistochemical studies showed similar proportions of T lymphocyte subtypes in psoriasis of HIV-positive patients and in psoriasis of immunocompetent hosts (219). Furthermore, there is evidence of identical keratinocyte expression of γ-IFN-induced IP-10 in both groups (167). These two findings suggest that the cellular immune reactions involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis may be similar in AIDS and non-AIDS patients (219).

Differential Diagnosis. Two histologic features are of great value in the diagnosis of psoriasis vulgaris: (a) mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils at their summits (Munro microabscesses) and (b) spongiform micropustules of Kogoj in the uppermost layers of the spinous layer. Dilation and tortuosity of capillaries in the papillae may also help in the diagnosis. All other features, such as acanthosis with elongation of the rete ridges and parakeratosis, can be found also in chronic eczematous dermatitis, such as atopic dermatitis, nummular dermatitis, or allergic contact dermatitis, which then may appear to be “psoriasiform.” However, the elongation of rete ridges is uneven. Although mild spongiosis may be seen in psoriasis, the presence of marked spongiosis and especially of coagulated serum as evidence of crusting in the cornified layer are features speaking against psoriasis, except in psoriasis on volar skin, in which spongiosis may be prominent. In addition, eosinophils, which are commonly found in allergic contact dermatitis and mainly in HIV-positive patients, are rarely seen in the psoriatic infiltrate. Difficulties may arise in treated lesions of psoriasis and in those with superimposed allergic contact dermatitis secondary to topical treatments. Lichen simplex chronicus is considered in the differential diagnosis of fully developed psoriatic plaques. In contrast to psoriasis, it shows a prominent granular layer, more irregular acanthosis, and fibrosis of the papillary dermis with collagen bundles aligned perpendicular to the skin surface. Seborrheic dermatitis may be very difficult to distinguish from psoriasis vulgaris, especially if overlap occurs. Accentuated spongiosis, mounds of parakeratosis with neutrophils predominantly at the follicular ostia, and more irregular acanthosis are histologic features suggestive of seborrheic dermatitis. Pityriasis rubra pilaris shares some histologic features with psoriasis, namely, acanthosis and parakeratosis. However, it could be differentiated from well-developed lesions of psoriasis by the presence of thick suprapapillary plates, broader and shorter rete ridges, and a preserved granular layer and alternating ortho- and parakeratosis. It also lacks Munro microabscesses and neutrophils in the infiltrate (220). Although the Kogoj spongiform pustule is highly diagnostic of the psoriasis group of diseases, including reactive arthritis, histologically typical spongiform pustules may occur also in pustular dermatophytosis, bacterial impetigo, pustular drug eruptions, and candidiasis, particularly if pustules are clinically present (221). Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) and Gram stains are useful for identifying the infectious microorganisms. Aggregates of neutrophils with pyknotic nuclei within areas of parakeratosis may occur in conditions other than psoriasis, but they generally differ from Munro microabscesses by being larger and less well circumscribed and by often showing crusting.

Because of the clinical and, particularly, the histologic resemblance of the tongue lesions in pustular psoriasis with those seen in geographic tongue, it has been suggested that geographic tongue represents an abortive form of pustular psoriasis (222).

Principles of Management. Currently, while no cure for psoriasis has been established, multiple therapeutic options exist for its treatment. Evaluative tools for the severity of psoriasis, including the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) or the Physicians Global Assessment (PGA), and for psychosocial well-being, such as the Psoriasis Life Stress Inventory and Psoriasis Disability Index, are available to assist clinicians in assessing disease extent and severity prior to initiation of therapy (223,224). In addition to the severity of the disease and impact on quality of life, the age of the patient, cost, complexity of the treatment regimen, practicality, tolerability, safety, and patient preferences should also be taken into consideration when deciding on a management plan. Given the association of psoriasis with psoriatic arthritis, HIV, and cardiovascular disease and associated risk factors, patients with psoriasis warrant an evaluation for extracutaneous disease.

Topical agents are the mainstay of treatment for psoriasis for limited disease severity (usually <10% of the body surface area) and for patients with mild to moderate psoriasis, which account for approximately 80% of patients (225). Commonly used topical agents include topical corticosteroids, vitamin D analogs, retinoids, calcineurin inhibitors, coal tar, anthralin, and keratolytics. Small, resistant plaques may respond to intralesional steroid injections.

Phototherapy using NB-UVB plays an integral role in psoriasis treatment and can be used for both extensive disease and for limited disease with debilitating symptoms (225). Ultraviolet A (UVA) penetrates deeper into the skin and when combined with the administration of a topical or systemic psoralen to act as a photosensitizer and increase the local effect of the UVA treatments is referred as PUVA therapy. This can be associated with pigment darkening and an increased long-term incidence of squamous cell carcinomas, and these therapies should be used with great caution in individuals with fair skin and other risk factors for cutaneous carcinoma (225). In management of localized plaque-type lesions, 308-nm excimer laser phototherapy can be used to deliver targeted high UVB doses while sparing adjacent healthy skin. Ultraviolet light is locally immunosuppressive but typically lacks the cutaneous adverse effects of long-term corticosteroid use and the immunosuppression encountered with systemic agents and biologics.

For those patients with severe or recalcitrant disease or those with psoriatic arthritis, systemic therapy may be required. Methotrexate is a preferred agent when psoriatic arthritis is present in addition to cutaneous involvement (225). Patients must be carefully monitored for myelosuppression (manifested by low hemoglobin, white blood cell count, and platelets) and hepatotoxicity when on methotrexate. Cyclosporine can be used in low doses (3 to 5 mg/kg/day) for 1 to 2 years, and is very effective for widespread disease requiring rapid control (225). However, nephorotoxicity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, electrolyte imbalance, and potential drug interactions should all be closely monitored. Acitretin is a systemic retinoid that may be effective when used in combination with topical treatments and may serve as a complement to phototherapy given their efficacy in reducing skin cancers, a common occurrence as a result of photodamage (226). As with other systemic agents, patients on acitretin must be monitored, in particular for hyperlipidemia and hepatotoxicity; its teratogenicity also restricts its use in women of childbearing potential (225).

In recent years, biologics have risen to the front lines in the armamentarium of psoriasis treatment. There are currently three biologic agents that specifically target TNF-α and are FDA-approved for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Infliximab, the first biologic to be used, represents a chimeric monoclonal antibody composed of a human IgG1 Fc portion and a predominantly murine Fab portion (227). It targets both soluble and membrane-bound TNF-α, and the binding of the latter results in T-cell apoptosis. Etanercept is a soluble dimeric fusion protein that links the p75 TNF-α receptor protein to the Fc portion of IgG1 (227). This agent is able to bind to soluble TNF-α, decreasing its free concentration in serum. Adalimumab is a fully humanized immunoglobulin monoclonal antibody that binds and neutralizes both soluble and membrane-bound TNF-α (227). On the PASI scale, all three biologic agents demonstrated efficacy in reducing moderate to severe psoriasis after a 12-week period of use when compared to placebo (226). However, all three biologic agents are considerably more costly than traditional systemic agents, and patients must be monitored at baseline as well as following regular treatment intervals for symptoms of infection, reactivation tuberculosis, malignancy, and demyelination of nerve fibers (228,229).

Newer biologic agents have also entered the market for use in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Ustekinumab is a monoclonal antibody targeting the shared p40 subunit of IL-23 and IL-12 and is currently in use (227). Other IL-23 pathway inhibitors under development include secukinumab (a fully humanized IgG1κ monoclonal antibody that selectively binds and neutralizes IL-17A) (230), ixekizumab (a humanized IgG4 monoclonal antibody that also neutralizes IL-17A) (230), and apilimod (a small-molecule compound that selectively suppresses synthesis of IL-12 and IL-23) (231).

Several small molecules are also under investigation for psoriasis treatment. These potential new drugs take advantage of recent advances in the understanding of the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Agents currently being studied include A3 adenosine receptor agonists, Janus kinase inhibitors, and phosphodiesterase inhibitors (230).

REACTIVE ARTHRITIS (FORMERLY REITER SYNDROME)

Clinical Summary. Reactive arthritis, formerly called Reiter syndrome (232,233), is a sterile arthritis associated in most cases with a distant infection causing enteritis or urethritis. Reactive arthritis predominantly affects young men, during the third decade of life (234), although some cases in women and children have been reported (235,236).

Reactive arthritis is a syndrome characterized by the triad of nongonococcal urethritis, arthritis, and conjunctivitis. However, only one third of the patients show the complete classic triad (237). There is great variation in the severity, number, and timing of clinical manifestations (238).

Mucocutaneous lesions occur in about half of affected patients. Lesions have a predilection for glans penis (balanitis circinata), palms and soles (keratoderma blennorrhagicum), and the subungual regions (Fig. 7-16). Vulvar and oral mucosa can be also affected.

Figure 7-16 Reiter disease. Confluent erythematous scaly papules and plaques on the dorsum of feet and toes, with nail dystrophy. (Courtesy of Department of Dermatology, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.)

In uncircumcised men, balanitis circinata presents as superficial crusted erosions forming a serpiginous pattern. In circumcised men the condition presents as erythematous hyperkeratotic and coalescent papules on the glans. Lesions on the palms and soles are erythematous, mollusk-like plaques with central keratotic excrescences. Pustular lesions may also develop. The subungual lesions consist of hyperkeratosis with opacification of the nail plate, and eventual shedding of the nail plate may occur. The prevalence of reactive arthritis in HIV-infected individuals is less than 1%; however, the disease appears to be more severe in immunocompromised patients (239).

Histopathology. Early pustular lesions on the palms or soles show a spongiform macropustule in the upper epidermis (240,241). In addition, one observes parakeratosis and elongation of the rete ridges.

As the lesions age, the parakeratotic cornified layer thickens considerably, which correlates with the keratotic excrescences seen clinically. The parakeratotic cornified layer is intermingled with the pyknotic nuclei of neutrophils. In old lesions, spongiform pustules are no longer seen, and the histologic picture shows acanthosis and orthokeratosis with only a few areas of parakeratosis, but occasionally the histologic picture resembles that of psoriasis (240).

Pathogenesis. The pathophysiology of reactive arthritis is thought to have both infectious and immune components. It can be caused by microorganisms that infect the urogenital or gastrointestinal systems, such as Chlamydia trachomatis, Ureaplasma urealyticum, Shigella flexneri, Clostridium difficile, Salmonella, Campylobacter, Cyclospora, and Yersinia species (238).

Chlamydia trachomatis has been cultured from urethral samples in nearly half of the patients and is believed to be capable of triggering reactive arthritis in susceptible men (242). Although joint cultures are negative for bacteria in reactive arthritis, hybridization studies have detected chlamydial RNA in synovial specimens (243). The occurrence of reactive arthritis after bacille Calmette–Guérin immunotherapy for bladder cancer has been reported (244). Eighty percent of patients with reactive arthritis are HLA-B27 positive (239); however, the precise role of this major histocompatibility class I antigen in the development of this disease is not known. There is no proof that microbial antigens can cross-react with HLA-B27 (245). One study found decreased IL-2 production in HLA-B27-positive and B7-positive patients who developed reactive arthritis after Salmonella infection. These findings suggest that an impaired cellular immunity against the infectious agent may be associated with development of the disease (246). First line of host defense involves Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which may act as pathogen sensors. Recent studies have shown that certain TLR-2 genetic variants but not TLR-4 were associated with reactive arthritis (247).

A close relationship to psoriasis has been assumed for the cutaneous lesions because of their clinical resemblance to psoriasis and the presence of spongiform pustules (248,249). Similarly, the arthritis of reactive arthritis resembles that of psoriasis not only clinically but also by the absence of rheumatoid factor (238).

Differential Diagnosis. The early spongiform pustule seen in skin lesions of reactive arthritis is indistinguishable from the spongiform pustule seen in pustular psoriasis. Clinicopathologic correlation may be needed to confirm the diagnosis. Slightly older lesions often can be identified as representing reactive arthritis, in contrast to psoriasis, by the presence of a markedly thickened cornified layer.

Principles of Management. Reactive arthritis has a variable course; it may resolve spontaneously or progress to cause permanent damage to the affected joints (240). There is no consensus about the use of antibiotics in reactive arthritis, because their efficacy is uncertain (250). Symptomatic treatment is recommended for arthritis and includes nonsteroidal anti-inflamatory drugs, analgesics, and intra-articular steroid injections. More severe cases may require immnosupressive drugs such as systemic corticosteroids or methotrexate (251). Cutaneous lesions can be treated similarly to psoriasis with topical steroids and salicylic acid. When required, systemic treatments such as etretinate, UVA phototherapy, methotrexate, and cyclosporine have been reported effective (252,253). Careful management is required in patients with severe reactive arthritis and HIV. Acitretin has been reported to improve skin and joint symptoms and to be safe for use in immunosuppressed patients (254).

DIGITATE DERMATOSIS (SMALL PLAQUE PARAPSORIASIS)

Clinical summary. There are three entities described as parapsoriasis: small-plaque parapsoriasis, large-plaque parapsoriasis, and parapsoriasis variegata.

Large-plaque parapsoriasis and parapsoriasis variegata are best considered as early stages of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma/mycosis fungoides (255). These are discussed further in Chapter 31.