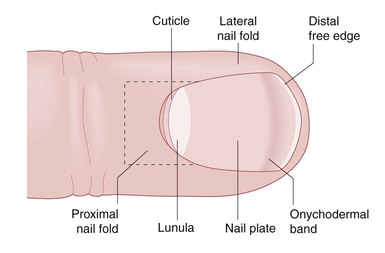

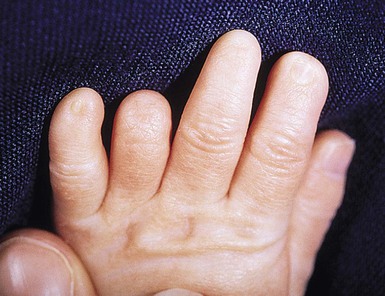

Robert A. Silverman, Adam I. Rubin Nails are specialized cutaneous appendages composed of hard keratins similar to those found in hair, and are unique to primates. In humans, nails function as a stabilizing unit to aid in tactile sensation, grasping, and scratching. Well-manicured or adorned nails in adolescents and adults may be perceived as an attribute of social acceptability and serve as a source of personal satisfaction. Although abnormalities of the nails are rare, they may affect an individual’s self-esteem and their relationships with others. Abnormal nails in a neonate or infant may be indicative of a more widespread inherited or sporadic syndrome, or they may be a localized congenital malformation. In either case, parents may be concerned about their child’s nails, sometimes out of proportion to the magnitude of any other problems that may be present. Investigation and consultations to uncover any associated illness and to allay any untoward parental anxiety are warranted. The nail unit is composed of a rectangular nail plate bordered by proximal and lateral nail folds (Fig. 32.1).1 The cuticle attaches the proximal nail fold to the nail plate. This acellular membrane is tightly adherent and prevents invasive microorganisms reaching the underlying matrix. The lunula (half moon) represents the distal portion of the nail’s proliferative matrix. The ventral side of the nail plate has longitudinal ridges that orient the direction of growth from the root over a complementary grooved nail bed. At birth, the dorsal surface of the nail displays unique, somewhat oblique ridges as well. These ridges become parallel and disappear slowly, and over time, the surface becomes smooth. The distal free edge of the plate separates from the bed at the hyponychium. The shape of the nail plate is convex. It is normally thickest at its proximal portion and thins distally. The size of the nail plate is determined by the size and growth of the underlying distal phalanx. Because embryologic development occurs in a cephalocaudal direction, it is not surprising that at birth, especially in premature infants, toenails may be smaller than fingernails. In premature infants, less than 32 weeks’ gestation, nail plates may not extend beyond the distal groove of the hyponychium. In postmature infants, such as macrosomic infants or infants of diabetic mothers, the nail plate may extend well beyond the hyponychium. In adults, it is estimated that fingernails grow 0.1 mm/day and toenails grow 1 mm/month. Similar data in newborns and infants are not available. Box 32.1 lists pathologic factors that affect nail growth. The anatomic structure of the nail unit is affected by many disease states.1 Conditions may be primary or secondary, localized or generalized, congenital or acquired. They can be associated with genetic syndromes, or drug exposures, or with infectious or systemic disease. Nail morphogenesis begins during the 9th week of gestation and is completed by the end of the second trimester (see Chapter 1). Beau’s lines are transverse grooves or moat-like depressions that extend across the nail plate from one lateral nail fold to the other.2,3 This deformity is a manifestation of nail matrix arrest and is first observed adjacent to the proximal nail fold. Beau’s lines slowly move toward the distal free edge of the nail plate as nail growth resumes. If the rate of nail growth is known, one can estimate the date of nail matrix arrest by measuring the distance between the proximal nail fold and the Beau’s line. Causes of Beau’s lines include high fevers caused by infection, severe cutaneous inflammatory diseases such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome or Kawasaki disease, a reaction to medications, and acrodermatitis enteropathica. Beau’s lines may occur in infants, 4–10 weeks of age, as a result of the stress of delivery. They have also been reported at birth as a result of intrauterine stress in a premature infant (Fig. 32.2).4 Although Beau’s lines should develop on all fingernails and toenails, they are usually most prominent on the thumb and great toe nails because of their slower rate of growth. Onychomadesis refers to proximal separation of the nail plate from the nail bed. Latent onychomadesis occurs when the nail separates some time after a profound interruption in nail growth. Causes are similar to those that produce Beau’s lines and may occur during the neonatal period as well. There is a close interaction between the formation of epidermal appendages and mesoderm during embryologic development. Therefore, it is not surprising that there are many alterations of nail shape that are linked with distant or underlying malformations of bone. It is not uncommon for newborns to have variations of the normal convex curvature of the nail. Koilonychia refers to nails that exhibit a concave or spoon shape.5 This may be a normal variant in newborns, especially when it involves the great toe nails. As the child grows and the distal phalanges lengthen, koilonychia gradually improves. Recently, a case of koilonychia, dome-shaped femoral epiphyses, and platyspondylia has been described.6 It is widely accepted that koilonychia in infants and toddlers may be indicative of iron deficiency.7 However, no well-controlled studies of iron deficiency in large numbers of infants with and without koilonychia have been reported, and improvement of nail shape with the administration of iron has not been documented. Familial koilonychia has also been reported.8 It has been described with other ectodermal defects such as monilethrix, palmoplantar keratoderma, and steatocystoma multiplex, as well as Turner syndrome.9 Other deformities in nail shape include pincer nails, claw nails, and racquet nails. Pincer nails are characterized by a transverse overcurvature of the nail plates.10 The condition is usually acquired, but some cases may result from an inherited developmental anomaly. If the convex transverse overcurvature is prominent, nails may appear similar to those in patients with pachyonychia congenita and occasionally may be quite painful. Congenital claw-like nails have also been reported.11 The nail plates have a dorsal convexity and then curve downward to resemble onychogryphosis. This is usually noted on the second to fourth toes and may be associated with a cleft hand. Hypoplasia of the distal phalanx with absence of the ossification center is observed on radiographs of the affected digits.12 Correction of the deformity is desirable because of the tendency toward recurrent bleeding and ulceration of the tip of the toe. Some authors distinguish claw nails from another isolated ungual anomaly, congenital curved nail of the fourth toe.13 Nails in these cases are normal thickness and have a longitudinal overcurvature. This trait may be sporadic or inherited, and is also associated with underlying distal phalangeal deformities.14 It may not come to medical attention until traumatic dystrophy occurs later in childhood. Racquet nails occur when the width of the nail plate exceeds its length, also referred to as brachyonychia. It may be a sign of foreshortening of the terminal phalanx and may be associated with other congenital anomalies.15 Clubbing is a curved or beak-like deformity of the nail unit that accompanies hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the fibrovascular support stroma of the distal phalanx. It is an acquired sign of both systemic and hereditary diseases.1 In neonates or infants, clubbing may be an early manifestation of cyanotic congenital heart disease, bronchopulmonary diseases, or HIV disease.16,17 Anonychia refers to the absence of nails. The most widely known association is with nail–patella syndrome (see below). Isolated congenital anonychia has been reported in families with both autosomal recessive18,19 and autosomal dominant inheritance. Rudimentary nail units may be evident, but the underlying phalangeal structure is normal. Anonychia and hypoplasia of the nails may be observed with absence of the distal phalanges and foreshortening of the affected digits (Fig. 32.3). Anonychia has been reported with limb defects,20 ectrodactyly,21 flexural pigmentation,22 isolated to the thumbnails,23 and with sensorineural hearing loss.24 These latter cases have been termed DOOR syndrome (deafness, onycho-osteodystrophy, and retardation). Elevated urinary amino acids have been detected in some patients with DOOR syndrome.22 Anonychia of the fifth fingers and toenails is characteristic of Coffin–Siris syndrome.25 Other features include growth and mental retardation, generalized hypertrichosis and scalp hypotrichosis, lax joints, and abnormal facies. Anonychia, nail hypoplasia, and other nail anomalies, such as double nails (Fig. 32.4), may occur as isolated findings.26 Infants with junctional and dystrophic forms of epidermolysis bullosa (EB) frequently have anonychia at birth (Fig. 32.5).27 Subungual hemorrhages, onycholysis (separation of the nail plate from the nail bed) and onychomadesis precede nail loss. One or more fingernails are usually affected. The periungual tissues and nail beds are frequently swollen and inflamed. Granulation tissue develops quickly. Meticulous hygiene, application of topical antibiotics, and wound care with synthetic dressings may optimize regrowth if possible. It is the authors’ opinion that in utero sucking of the fingers results in most of the nail disease that is present at birth in EB. Small nails may be localized to one or a few digits or involve all of the nail fields (Fig. 32.6). Conditions associated with micronychia are listed in Table 32.1.28–32 Current theory suggests that at least some forms of micronychia, such as in fetal alcohol syndrome and exposure to anticonvulsants, are due to inhibition of retinoic acid synthesis during early embryologic development.33,34 Selected specific causes of micronychia are discussed in subsequent sections. TABLE 32.1 Causes of micronychia a X-linked recessive inheritance. Nail–patella syndrome, also known as hereditary osteo-onychodysplasia (HOOD), is an autosomal dominant genodermatosis characterized by nail hypoplasia present at birth, chronic progressive nephropathy, and hypoplastic patellae that may result in debilitating osteoarthritis. This disorder has a high degree of penetrance and widely variable expressivity.35 Nail disease is usually the only manifestation in neonates. However, there are rare reports of infants with proteinuria, signifying the early onset of renal pathology.36 Ungual manifestations are most prominent on the ulnar sides of the thumbs and index fingers, and to a lesser degree on other digits. They include micronychia, hemionychia, and occasionally anonychia. If present, a triangularly shaped lunula with a distal apex is nearly pathognomonic for the condition.37 Nail plates may be thin and display koilonychia, which can lead to frequent chipping and splitting later in childhood. Skeletal deformities are not visible until ossification centers develop. Parents may be screened for small, easily subluxed patellae, characteristic posterior iliac horns, hypoplasia of the proximal radius and ulna, scoliosis, and thickened scapulae. Generally, patients with nail–patella syndrome are not identified until early adulthood, when knee dislocation, pain, and gait disturbances bring them to medical attention.38 Renal disease that presents as asymptomatic proteinuria is the most serious manifestation of nail–patella syndrome. It is usually not apparent until adulthood, but a newborn and a 2-year-old child with nephrosis have been reported.39 Renal biopsies have uncovered glomerulonephritis secondary to glomerular basement membrane zone thickening from collagen fibril deposition. These findings have even been noted in a spontaneously aborted 18-week-old fetus.40 Other manifestations include heterochromic irides, colobomas, microcorneas, glaucoma,41 popliteal pterygia, and mild mental deficiency. It has been suggested that these, as well as other findings such as colon cancer, in specific kindreds may be a result of contiguous gene defects, translocations, or other genetic aberrations.42 Complications from cerebral and large vessel dilation have also been reported, and are also caused by collagenous basal lamina reduplication.43 Mutations in the LIM homeodomain protein gene LMX1b have been demonstrated in the region of 9q34 and result in the nail–patella syndrome.44 This gene is responsible for dorsoventral body pattern formation during fetal development. It is linked to the ABO blood group and had been believed to be an abnormality in COL5A1, which is necessary for the production of collagen type V, an important component in the glomerular and other basement membrane zones.45 Congenital onychodysplasia of the index fingers (COIF), also now known as Iso–Kikuchi syndrome, was first described in 1969.46,47 Original cases were congenital, limited mainly to the index fingers, and characterized by anonychia, micronychia, and/or polyonychia (Fig. 32.7). They were nonfamilial and nonhereditary, and without underlying bone or joint abnormalities. Since that time, the clinical criteria have been changed or expanded to encompass a number of additional observations.48 Although the index fingers are most commonly affected, onychodystrophy has been reported on other fingers and toes.49,50 Malalignment, ‘rolled micronychia,’ hemionychogryphosis, onychoheterotopia, and polyonychia with syndactyly have also been detailed. Unlike nail–patella syndrome, abnormalities in the nail unit are more prominent on the radial aspects of the digits. A Y-shaped bifurcation of the distal phalanx on lateral radiographs is frequent and is characteristic of the condition.51 Familial cases have also been documented.52 The pathogenesis of congenital onychodysplasia is poorly understood. An abnormal vascular supply, anomalies from an abnormal grip, external deformation from pressure against the cranium, exposure to teratogens, and genetic influences have been implicated by a number of authors.50 It is quite possible that the clinical findings may be explained by any of these theories if the inciting event occurs at a specific time during the embryologic development of the nail unit. Onychoatrophy refers to a progressive reduction in size and thickness of the nail unit. The term is usually used to describe acquired dissolution of ungual structures and should not be used synonymously with micronychia, although some authors do so. Inflammatory disorders, which are observed in older children and adults, but rarely documented in newborns and infants, such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome or graft-versus-host disease, may result in onychoatrophy. Infants with congenital disorders that have a progressive phenotype, such as acrogeria or dyskeratosis congenita, can have onychoatrophy as well. Occlusion of the digital artery by emboli may result in phalangeal necrosis and destruction of nail structures. Other postnatal vascular insults, such as extensive aplasia cutis congenita or disseminated intravascular coagulation from homozygous protein C deficiency, could potentially have similar effects. Onychoheterotopia, or ectopic nails, occurs when ungual tissue develops on areas other than the dorsal aspect of the distal phalanx.50 Cases that have been reported tend to involve the palmar surface of the fifth fingers.53–56

Nail Disorders

Introduction

Beau’s lines

Alterations in nail shape

Alterations in nail size

Micronychia

Disorder

Clinical manifestations

Nail-patella syndrome

Small or absent patellas, iliac horns, triangular lunulae

Congenital onychodysplasia

Ectodermal dysplasias

Variable sweating, hair and tooth abnormalities

Congenital malalignment of index fingers

None, except underlying phalangeal malformation

Fetal teratogens

Alcohol

Microcephaly, short palpebral fissures, maxillary hypoplasia

Hydantoins (and other anticonvulsants)

Short stature, retardation, hypertelorism, depressed nasal bridge, cardiac anomalies, mucosal changes

Polychlorinated biphenyls

Natal teeth, pigment anomalies, mucosal changes

Warfarin

Nasal hypoplasia, stippled epiphyses

Chromosome and genetic abnormalities

Coffin–Siris syndrome

Hypoplasia of the fifth digit, lax joints, blepharoptosis, and multiple genetic mutations

Dyskeratosis congenita

Hyperpigmentation and hypopigmentation, Fanconi-like anemia, blepharitis, leukoplakia, XLRa and DKC1 mutation

Adams–Oliver syndrome

Large defects of aplasia cutis of the scalp with cutis marmorata, congenital heart malformations and transverse limb reduction defects, DOCK6 and RBPJ mutations

Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome

Macrosomia, abnormal facies, supernumerary nipples, polydactyly, heart defects, X-linked GPC3 mutation

Trisomies

3q, 8, 13, 18

Turner syndrome

XO, webbed neck, nevi, lymphedema, coarctation of the aorta

Noonan syndrome

XY male with a Turner phenotype and pulmonic stenosis

Amniotic bands

Hypoplasia of the distal phalanx associated with aplasia cutis

Nail–patella syndrome

Congenital onychodysplasia of the index fingers

Onychoatrophy

Ectopic nails

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nail Disorders

32