8. Multimodal Analgesia for the Aesthetic Surgery Patient

Girish P. Joshi, Jeffrey E. Janis

UNDERSTANDING MULTIMODAL PAIN MANAGEMENT

■ “Prescription drug overdose is an epidemic in the United States. All too often, in far too many communities, the treatment is becoming the problem.”1

■ 80% of patients experience acute pain after surgery.

■ 75% of U.S. patients report surgical pain rated 7 or higher (scale of 1–10).

■ 59% of patients are concerned about postoperative pain.2

OPIOID EPIDEMIC

■ November 2016: U.S. Surgeon General declares epidemic of addiction—public health crisis3

■ United States contains 4.6% of the world’s total population, but consumes two thirds of the world opioid supply.

■ 12.5 million people, or 4.7% of the American population, aberrantly used prescription opioids in 2015.4

■ 1% of the U.S. population is addicted to opioids.

■ 2015: 28,647 people died in the United States due to prescription opioid overdose

■ Prescription opioid use disorder is estimated to cost the American economy $53.4 billion per year.

■ Resurgence of heroin

• Cheaper

• Inappropriate weaning strategies from prescription opioids

■ Four fifths of heroin users report their initial exposure to opioids was to prescription opioids.5

■ 2007: Prescription opioid overdose responsible for more deaths than heroin and cocaine combined 6

■ 1996–2006: Rate of prescription opioid use disorder increased by 167%7

• Rates continued to rise

PRESCRIBING PATTERNS AND DEATHS

■ In patients with opioid prescriptions that overdose, the mortality rate increases with escalating dose.8

■ Increases in opioid prescription rates have not resulted in improvement in patient disability or health outcome.9

STATISTICS

■ Accidental deaths per year in United States10:

• #1: Drug poisoning

► 40% of drug poisonings are due to opioid overdose.

• #2: Automobile accidents

• 2015: United States—5.4% of high school seniors aberrantly used prescription opioids within the last year11

► 40% stated that these drugs were easy to get.

• 2016: Canada—20.6% of grade 12 high school students aberrantly used opioid medication in the last year12

► 70% obtained the medication from their own homes.

• 44 Americans die every day of a prescription overdose.13

► For every death there are:

♦ 10 treatment admissions for abuse

♦ 32 Emergency Department visits for misuse or abuse

♦ 130 people who abuse or are dependent

♦ 825 nonmedical users

DIVERSION

■ Illicitly obtained prescription opioids are often obtained from friends or family.

■ 2006–2010: Street availability of prescription opioids increased

■ 2010: 40% of Medicaid patients with opioid prescriptions had indicators of aberrant use or diversion14

SURGEON’S ROLE

■ Surgeons responsible for 9.8% of the total opioid prescriptions in the United States15

■ Rates of opioid prescriptions to opioid naive patients after minor surgery increased between 2004 –2012.16

■ Surgeons may play a significant role in propagating the addiction crisis by exposing patients to potentially harmful and addictive opioid medications and contributing to the street supply of opioids.

■ Simple education interventions for patients to explain how to safely store and dispose of opioid medications can make a significant impact.

■ Led by the surgeon and a written handout or referral to a website which explains proper opioid storage and disposal

PROPER STORAGE AND DISPOSAL

■ Opioids should be stored in a locked cabinet.

■ All unused medication should be returned to the pharmacy or destroyed once postoperative pain has resolved.

SURGERY AND ADDICTION

■ Patients who were opioid naive before surgery shown to have a significant chance of persistent postoperative opioid use.17

■ Many patients continue to receive opioids chronically after initially receiving them for postoperative pain control.

■ Patients taking opioids chronically prior to surgery have an increased chance of still taking them 1 year later when compared with controls.

OPIOIDS AND SURGERY

■ A 2016 study of elective hand surgery patients showed 13% were still taking opioids 90 days after surgery.18

■ Another study found that 3.1% were still taking opioids at 90 days after major surgery.19

■ Total knee arthroplasty: 1.4% chance of still taking opioids one year after surgery20

• Odds ratio of 5:1 when compared to nonoperated controls

• Another study found that older patients (>66 years old) following low-risk surgery have a 44% increased likelihood of chronic use at 1 year compared with controls.21

CAUTION: Surgery is a risk factor! There is a risk of persistent opioid use following exposure to opioid medications in the perioperative period, even in opioid naive patients.

RISK FACTORS FOR OPIOID ABUSE

■ History of substance use disorder

■ Comorbid psychological health conditions (i.e., anxiety, depression)

■ Male sex

■ Low socioeconomic status

LEFTOVERS AND DISPOSAL

■ Elective hand surgery study (2012): 95% received opioids with average 30 doses22

■ 19 doses left over after acute pain resolution

■ Urology: 92% received no instructions on how to dispose of leftover opioids after surgery23

• 67% had leftover opioids

• 91% of the patients with leftovers went on to keep them in an unlocked medicine cabinet24

■ Oral surgery and pediatric surgery: similar to above

■ Thoracic and gynecological surgery: 83% had leftover opioid medication

► 71%–73% stored the leftovers unsafely

SENIOR AUTHOR TIP: Since most people with prescription opioid use disorder get them from friends and family, it is reasonable to conclude that our postoperative analgesia prescription practices are making a significant contribution to the supply of illicit opioids.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR SURGEONS

■ Consider the risk that an individual patient may develop persistent opioid use and proceed to an opioid use disorder.

■ Consider the risk that medications prescribed postoperatively may end up diverted to nonmedical use and causing direct public health harm.

■ Identify risk factors:

• Psychiatric illness

• History of either aberrant substance use or diagnosed substance use disorder

• Communicate to the patient in a nonjudgmental way so that they can exercise caution in taking prescribed medications.

■ Patients with an established or suspected substance use disorder should be referred to an addiction specialist preoperatively if possible.25

■ Elective surgery in patients with established substance use disorders should not be performed until follow-up for substance use has been arranged.

■ Efforts should be made to explain and facilitate the use of nonopioid pain control.

■ Prescriptions should be limited to 20 doses of low potency, immediate release opioids unless circumstances clearly dictate otherwise.26,27

SENIOR AUTHOR TIP: We can make a major contribution by curbing opioid diversion in the perioperative period. We can partner with our anesthesia/pain colleagues to identify at-risk patients and prevent postoperative aberrant opioid use.

CAUTION: If an opioid naive patient develops an opioid use disorder after surgery, that is a surgical complication. Similarly, if members of our patient’s family (i.e., children, home care workers, etc.) aberrantly use the medications we prescribe, we hold a level of responsibility for this.

PROPER PAIN MANAGEMENT

Multiple organizations have urged a shift toward nonopioid options for pain management.

■ JCAHO27:

• “An individualized, multimodal treatment plan should be used to manage pain—upon assessment, the best approach may be to start with a non-narcotic”1

■ CDC28:

• “Health care providers should only use opioids in carefully screened and monitored patients when non-opioid treatments are insufficient to manage pain”2

■ ASA29:

• “A multimodal approach to pain management beginning with a local anesthetic where appropriate”3

IMPACT OF INADEQUATE PAIN MANAGEMENT30

■ Undesirable physiologic and immunologic effects

■ Associated with poor surgical outcomes

■ ↑ probability of hospital readmission

■ ↑ cost of care

■ ↓ patient satisfaction

■ Postsurgical pain intensity was associated with delayed wound healing.

APPROACH TO PAIN MANAGEMENT

■ Common pain management protocols are opioid based.

■ Lack understanding of current literature

■ Don’t differentiate between acute and chronic pain

■ Aren’t customized to patients or surgical procedures

OPIOID-RELATED ADVERSE EVENTS31

■ Primary component of most postoperative multimodal pain management strategies

■ Associated with unwanted and severe adverse events

• Nausea and vomiting

• Pruritus

• Sedation and cognitive impairment

• Urinary depression

• Sleep disturbances

• Respiratory depression

ANALGESIC OPTIONS FOR MULTIMODAL ANALGESIA

■ Regional analgesic techniques

• Wound infiltration

• Field blocks (TAP block)

• Peripheral nerve and plexus blocks

• Neuraxial blocks

■ IV lidocaine infusion

■ Acetaminophen

■ NSAIDs

■ COX-2 inhibitors

■ Dexamethasone

■ Ketamine

■ Gabapentin/pregabalin

■ Opioids (as rescue)

BENEFITS32,33

■ Improve postsurgical pain control

■ Permit use of lower analgesic doses

■ Reduce dependence on opioids for postsurgical pain management

■ Combines a variety of analgesic medication and techniques with nonpharmacological interventions34

• Uses drugs with complimentary mechanisms of action

• Targets multiple sites of the nociceptive pathway

• Allows for lower doses of medications and potentially provides greater pain relief

■ May result in fewer analgesic side effects

■ May address patient differences in analgesic metabolism and pain sensitivity

■ Avoid “shotgun” approach

■ Type and number of analgesics should be procedure- and patient-specific

■ Emphasis on function NOT pain scores

ACETAMINOPHEN, NSAIDs, AND COX-2 INHIBITORS COMBINATION

■ Meta-analysis of opioid-sparing effects of acetaminophen, NSAIDs, and COX-2 inhibitors

■ All analgesics resulted in lower 24-hour morphine requirement (6–10 mg).

■ No clinically significant advantages shown for one group over the others

■ NSAIDs associated with more bleeding

• NSAIDs versus Coxibs

► No difference in analgesic efficacy between nonselective-NSAIDs and COX-2 selective inhibitors at equipotent doses

► COX-2 inhibitors lack of platelet inhibition and do not influence perioperative blood loss

► No difference in other adverse effects (cardiovascular, renal, gastrointestinal)

PERIOPERATIVE DEXAMETHASONE AND PAIN

■ Systematic review of published literature that involved 45 studies, involving 5796 patients

■ Benefits (as per systematic review):

• Reduced pain scores at 2 hours and 24 hours postoperatively

• Reduced opioid requirements

• Reduced need for rescue analgesia for intolerable pain

• Allowed longer time to first rescue analgesic

• Allowed shorter PACU stay

■ No increase in infection or delayed wound healing

■ No dose response with regards opioid sparing

GABAPENTIN/PREGABALIN FOR POSTOPERATIVE PAIN35,36

■ Reduces postoperative pain and opioid requirements

■ Limitations: Studies have small sample size and short duration of follow-up

■ Side effects: Sedation, dizziness may delay discharge home

■ Selective use in surgical procedures with high incidence of persistent postoperative pain

• Patients with fibromyalgia, chronic pain

INTRAVENOUS KETAMINE

■ Systematic review placebo-controlled, RCTs (n = 47) IV ketamine (bolus or infusion)

■ Heterogeneity among studies was significant

■ Reduced total opioid consumption and increase in time to first analgesic observed in all studies

■ Reduced pain scores

■ Reduced PONV only when pain scores decreased

■ Not beneficial for surgery with mild pain (VAS <4)

■ Hallucinations and nightmares significantly high when ketamine was efficacious

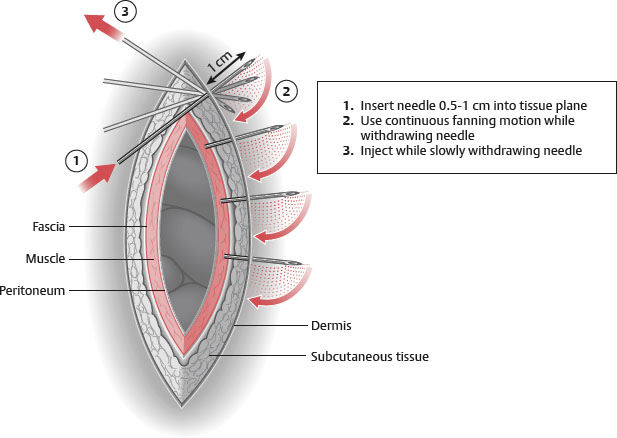

INFILTRATION OF LOCAL ANESTHETICS

TIMING

■ Timing of the block (preincision versus postincision) does not appear to be clinically significant.

■ Nerve blocks improve postoperative analgesia.

■ Total dose, but not volume and concentration, of local anesthetics affects the efficiency.