9. Safety Considerations in Aesthetic Surgery

Jeffrey E. Janis, Sumeet Sorel Teotia, J. Byers Bowen, Girish P. Joshi, Vernon Leroy Young

“The physician must … have two special objects in view with regard to disease, namely, to do good or to do no harm.”1

Hippocrates

SAFETY IN OFFICE-BASED SURGERY

■ Two decades ago <20% of surgical procedures were performed on an outpatient basis.

■ Today >80% of all surgeries are performed in an outpatient setting.2

■ Numerous studies have established the efficacy and safety of outpatient office-based surgical facilities.

■ These studies have shown low complication rates of 0.33%-0.7% and extremely low mortality rates of approximately 0.002%.2–6

■ The two largest plastic surgery societies in the United States, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS) and the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ASAPS), have recognized the importance of establishing a culture of safety and have accordingly established task forces that are charged with establishing guidelines for office-based surgical facilities.

■ In their review of patient safety in an office-based setting, Horton, Janis, and Rohrich7 divided this topic into four broad categories:

1. Administrative

2. Clinical aspects

3. Liposuction

4. Management of postoperative issues, in particular postoperative pain and postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV)

ADMINISTRATIVE ISSUES7

■ Governance: Policies outlining the structure of office-based surgical facilities include staff responsibilities, supervision, and a patient bill of rights.

■ Physician qualifications: Practitioners must obtain and maintain adequate training and certification for all procedures/treatments performed in the office facility and should limit their practice to the scope of the certifying board.

■ Quality assessment: Develop a system of quality of care with continual evaluation focused on improving patient care/safety. This includes the maintenance of the physical plant, operating room/recovery room equipment, personnel evaluations and coursework, and development and implementation of protocols and procedures.

■ Accreditation and maintenance of surgical facility standards

■ Protocols for management of emergency situations. This includes transfer protocols to a higher level of care (i.e., hospitals), generally, where the surgeon has admitting privileges and ideally privileges to perform the same procedures that are performed in the office-based setting.

■ Informed consent process

■ Maintenance of complete medical records

■ Guidelines for patient discharge

■ System for reporting of adverse events

CORE PRINCIPLES

■ These core principles have been approved by the American College of Surgeons, the American Medical Association, and the ASPS for outpatient office-based surgery involving any level of anesthesia above local anesthesia procedures.8

• Core principle 1: Guidelines or regulations should be developed by states for office-based surgery according to levels of anesthesia defined by the ASA Continuum of Depth of Sedation statement dated October 13, 1999, excluding local anesthesia or minimal sedation.

• Core principle 2: Physicians should select patients by criteria, including the ASA Patient Selection Physical Status Classification System. This should be documented in the preoperative evaluation of the patient.

• Core principle 3: Physicians who perform office-based surgery should have their facilities accredited by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care, the American Association for Accreditation of Ambulatory Surgery Facilities, the American Osteopathic Association, or a state-recognized entity such as the Institute for Medical Quality, or the facility should be state licensed and/or Medicare certified.

• Core principle 4: Physicians performing office-based surgery must have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital, or have a transfer agreement with another physician who has admitting privileges at a nearby hospital, or maintain an emergency transfer agreement with a nearby hospital.

• Core principle 5: States should follow the guidelines outlined by the Federation of State Medical Boards regarding informed consent.

• Core principle 6: States should consider legally privileged adverse incident reporting requirements as recommended by the Federation of State Medical Boards and accompanied by periodic peer review and a program of Continuous Quality Improvement.

• Core principle 7: Physicians performing office-based surgery must obtain and maintain board certification by one of the boards recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties, the American Osteopathic Association, or a board with equivalent standards approved by the state medical board within 5 years of completing an approved residency training program. The procedure must be one that is generally recognized by that certifying board as falling within the scope of training and practice of the physician providing the care.

• Core principle 8: Physicians performing office-based surgery may show competency by maintaining core privileges at an accredited or licensed hospital or ambulatory surgical center for the procedures they perform in the office setting. Alternatively, the governing body of the office facility is responsible for a peer review process for privileging physicians based on nationally recognized credentialing standards.

• Core principle 9: At least one physician who is credentialed or currently recognized as having successfully completed a course in advanced resuscitative techniques (advanced trauma life support, advanced cardiac life support, or pediatric advanced life support) must be present or immediately available with age- and size-appropriate resuscitative equipment until the patient has met the criteria for discharge from the facility. In addition, other medical personnel with direct patient contact should, at a minimum, be trained in basic life support.

• Core principle 10: Physicians administering or supervising moderate sedation/analgesia, deep sedation/analgesia, or general anesthesia should have appropriate education and training.

CLINICAL ISSUES RELATED TO OFFICE-BASED SURGERY

■ Preoperative evaluation: This includes a thorough history and physical examination performed by the surgeon, with consideration for use of a standardized form to capture all information pertinent to a patient’s medical history, which would allow the surgeon to adequately assess the patient’s risk for surgery and optimize the outcome from the proposed procedure.

■ Anesthesia evaluation: For any procedure that requires >simple local anesthesia (i.e., sedation or general anesthesia), anesthesia should be given by a practitioner, either a certified nurse anesthetist or anesthesiologist, in accordance with the current specific state requirements where the surgical facility exists.

■ Patient selection in office-based surgery is an important concept.9,10

■ Patients should be risk stratified based on the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical classification status (Table 9-1).

• ASA I and II patients are considered ideal candidates for all types of office-based surgery.

• ASA III patients are considered reasonable candidates for procedures that can be performed using a local anesthetic with or without sedation (see Chapter 5).

• ASA IV patients are candidates for only local anesthesia procedures in an office setting.

• These are general guidelines and should be interpreted by each surgeon in consultation with the anesthesia practitioner.

Table 9-1 American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification

| Physical Status | Description | Example |

Class 1 | A normal healthy patient | Healthy, nonsmoking, no or minimal alcohol use |

Class 2 | A patient with mild systemic disease | Mild diseases only without substantive functional limitations. Examples include (but not limited to) current smoker, social alcohol drinker, pregnancy, obesity (BMI = 30-40), well-controlled DM/HTN, mild lung disease |

Class 3 | A patient with severe systemic disease | Substantive functional limitations; One or more moderate to severe diseases. Examples include (but not limited to) poorly controlled DM or HTN; COPD; morbid obesity (BMI ≥40); active hepatitis; alcohol dependence or abuse, implanted pacemaker, moderate reduction of ejection fraction; ESRD undergoing regularly scheduled dialysis; premature infant PCA <60 weeks; history (>3 months) of MI, CVA, TIA, or CAD/stents |

Class 4 | A patient with severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life | Examples include (but not limited to) recent (<3 months) MI, CVA, TIA, or CAD/stents; ongoing cardiac ischemia or severe valve dysfunction; severe reduction of ejection fraction; sepsis; DIC; ARD or ESRD not undergoing regularly scheduled dialysis |

Class 5 | A moribund patient who is not expected to survive without the operation | Examples include (but not limited to) ruptured abdominal/thoracic aneurysm; massive trauma; intracranial bleed with mass effect; ischemic bowel in the face of significant cardiac pathology or multiple organ/system dysfunction |

Class 6 | A declared brain-dead patient whose organs are being removed for donor purposes |

*The addition of “E” denotes emergency surgery. An emergency is defined as existing when delay in treatment of the patient would lead to a significant increase in the threat to life or body part.

MONITORING AND MINIMIZING PHYSIOLOGIC STRESSES RELATED TO THE SURGICAL PROCEDURE

HYPOTHERMIA

■ Definition: Core body temperature <36° C

■ Incidence: 50%-90% of surgical patients if no preventative measures are used.11

■ Causes:

• Thermoregulatory mechanisms are impaired by anesthesia.

• Core-to-peripheral heat redistribution begins soon after anesthesia.

• Patient loses body heat to ambient temperature of OR.12

■ Risks: Increased blood loss, coagulation disorders, increased risk of cardiac events, increased risk of surgical site infection, postoperative shivering, and lengthened hospital stays.

• All of these factors secondarily contribute to increased costs.13

■ Prevention: Use of cutaneous warming devices, forced-air warming blankets, and intravenous fluid warmers (see Chapter 5)

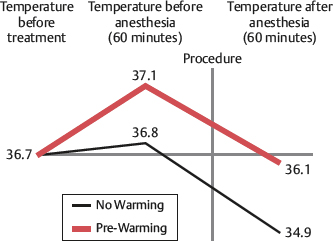

• Actively prewarm patients for 1 hour preoperative with forced-air heating

• Patients not prewarmed are prone to hypothermia within 30 minutes of anesthesia induction (Fig. 9-1).12

Fig. 9-1 Two-group comparison of prewarming.

■ Recommendations: If no antihypothermia devices are available, office surgical procedures should be limited to <2 hours’ duration and <20% body surface area of exposure.9

BLOOD LOSS

■ If the anticipated blood loss is >500 ml, the procedure should be performed in a facility in which postoperative monitoring and blood replacement products are readily available.9

DURATION OF THE SURGICAL PROCEDURE

■ Overall procedure length should be limited to <6 hours for office-based surgical procedures.9

■ The safety and efficacy of outpatient office-based surgery has been established by numerous studies.2–6

■ Some studies have correlated the length of the ambulatory surgical procedure with increased rates of postdischarge readmission to a hospital.14

■ State regulations must be checked for details, because some states have more aggressive regulations/restrictions.

POSTOPERATIVE PAIN AND NAUSEA

■ The postoperative management of office-based surgical patients affects the discharge process, the patients’ overall satisfaction with the procedure and facility, and ultimately patient safety.

• Inadequate pain control has physiologic effects on all organ systems.15

• Postoperative pain is the main reason for delayed discharge and hospital readmission after ambulatory surgery.16

• Inadequate pain control can also cause PONV.

• PONV has received less attention than pain management but actually represents the most common reason for patient dissatisfaction. It is also a major factor in delayed discharge and unplanned postoperative hospital admission.

► Up to 10% of patients experience PONV in the recovery room.15,17

► The incidence of PONV increases to 30% at 24 hours, and most patients have PONV after discharge with no access to treatment.17

► Long-acting narcotics and inhalational anesthetic agents should be avoided to reduce PONV.

► Propofol has been shown to have antiemetic effects.18

• Multimodal pain and PONV management are recommended in the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative phases of the office-based surgical procedure.

• Multimodal PONV involves treating all five major receptor systems19,20:

1. Serotonin (5-HT3): These are currently the most effective and safest agents.21

2. Dopamine (DA)

3. Histamine (H-1)

4. Acetylcholine (Ach)

5. Neurokinin (NK-1)

For additional details, see Chapters 7 and 8.

LIPOSUCTION

■ According to the 2016 American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank statistics, liposuction procedures (414,335) were the most commonly performed aesthetic procedures in the United States.22 Most of these procedures are performed in an office-based setting.

ANESTHESIA (see also Chapters 5 through 7)

■ For small-volume liposuction, infiltration with a solution containing a local anesthetic may be sufficient without the need for adjunctive anesthesia, although the use of monitoring devices during the procedure is recommended.

■ Bupivacaine (Marcaine) should not be used because of the severity of its side effects, its long half-life, and the inability to reverse toxicity.

■ Lidocaine maximal dosage is 35 mg/kg.23

■ For larger-volume liposuction, the amount of lidocaine used should be reduced.

■ Superwet (1:1) technique rather than tumescent (3:1) technique is used to reduce lidocaine dosage and infiltrate volume.

■ If regional or general anesthesia is used, not using or reducing the lidocaine dose should be considered.

■ Epinephrine: The recommended maximal dose is 0.07 mg/kg, although up to 10 mg/kg have been used safely.24

■ Epinephrine is avoided for patients with comorbid medical conditions that prohibit its use, including hyperthyroidism, severe hypertension, cardiac disease, peripheral vascular disease, and pheochromocytoma.

■ For multiple-site liposuction procedures, infiltration is staged to decrease the epinephrine effects.24

■ Patient selection: Liposuction is generally a safe procedure for treating localized adiposity of the abdomen, flanks, arm, trunks, and thighs. Liposuction is not a treatment for obesity. It is generally not recommended for patients with a BMI >30.25

VOLUME

■ In an office-based setting, the maximal volume of lipoaspirate should be 5000 cc.24 Large-volume liposuction (>5000 cc) should be performed in an acute facility that allows monitoring of fluid resuscitation requirements, and overnight observation/hospitalization should be strongly considered.

FLUID MANAGEMENT

■ Recommendations for fluid resuscitation are shown in Box 9-1.

Box 9-1 LIPOSUCTION FLUID RESUSCITATION GUIDELINES

| Small-Volume Aspirations (<5 liters) | Large-Volume Aspirations (>5 liters) |

| Maintenance fluida | Maintenance fluida |

| Subcutaneous infiltrateb | Subcutaneous infiltrateb 0.25 ml of intravenous crystalloid per millimeter of aspirate >5 liters |

aAmount of fluid to be replaced from preoperative, NPO status.

bSeventy percent is presumed to be intravascular.

COMBINATION PROCEDURES

■ Studies have shown a cumulative effect on the incidence of complications when multiple surgical procedures are combined in one setting.

■ Studies have shown that smaller-volume liposuction can be safely and effectively combined with other plastic surgery procedures, even in office settings.

■ Some states have recently restricted the combination of liposuction with any other type of surgery.

■ Surgeons operating in an office-based facility must be aware of the local and state regulations.

MORTALITY

■ A survey study of ASAPS members showed 95 deaths in close to 500,000 lipoplasty procedures for a mortality rate of 1 in 5224 (19.1/100,000 versus 3/100,000 for elective inguinal hernia repair)26 (Table 9-2).

Table 9-2 Fatal Outcomes from Liposuction

| Cause of Death | Number of Deaths | Percentage |

| Fat embolism | 11 | 8.5 |

| Anesthesia-related complications | 13 | 10.0 |

| Hemorrhage | 6 | 4.6 |

| Thromboembolism | 30 | 23.1 |

| Cardiorespiratory failure | 7 | 5.4 |

| Gastrointestinal perforations | 19 | 14.6 |

| Massive infection | 7 | 5.4 |

| Unknown or confidential | 37 | 28.5 |

| Total | 130 | ∼100 |

■ Pulmonary embolism (PE) was the most common cause of death (23%).

■ Overall lipoplasty mortality rates have been reported as 0.0021%-0.019%.26,27

COMBINATION SURGICAL PROCEDURES

■ After the 2000 Florida moratorium banned the combination of abdominoplasty and liposuction, interest in evaluating the safety and efficacy of combined plastic surgical procedures has increased.28

■ Many states have imposed arbitrary restrictions on allowable lengths of surgery for office-based surgery.

■ Florida mandates that procedures lasting >6 hours must not be performed in the office setting, whereas Pennsylvania and Tennessee have imposed arbitrary 4-hour limits on office-based surgery.

■ Balakrishnan et al29 reviewed the current available data and concluded: “As they [states] attempt to impose regulations on office surgery, it is evident that sufficient data do not exist to formulate immediate evidence-based policy.”

■ A review of the literature revealed that most studies have addressed the combination of abdominoplasty with either liposuction or gynecological procedures.30,31

■ Unlike previous reports,30,31 which were mainly retrospective reviews of the efficacy of combining abdominoplasty with gynecological procedures, these studies established the safety of office-based abdominoplasty and of performing concomitant aesthetic procedures with abdominoplasty.32,33

• Stevens et al (2006)32: Their study showed no statistically significant difference in complication rates between a group of patients who underwent abdominoplasty with a breast procedure compared with a control group who underwent abdominoplasty alone.

• Melendez et al (2008)33: Aside from a single episode of PE in their abdominoplasty-only group (incidence 1.03%), they reported no other major complications or mortality in either study group (i.e., abdominoplasty versus abdominoplasty with another aesthetic procedure).

• A 2006 retrospective Canadian study34 compared a group of 37 inpatient abdominoplasty procedures with 32 patients who underwent outpatient abdominoplasty. Most patients underwent concomitant aesthetic procedures. There was no significant difference in complications between the inpatient and outpatient groups.

■ Although these studies support the safety of combining aesthetic surgical procedures, both abdominoplasty and high-volume liposuction have been established as higher-risk surgeries for VTE,26,27,35 and it is prudent for surgeons to approach the combination of these two procedures with caution and maximize patient safety with appropriate VTE prophylaxis. In higher-risk patients these combination procedures should be performed in a hospital, or consideration should be given to not combining the procedures.

■ Gordon and Koch36 reviewed 1200 consecutive facial plastic surgeries performed in an office-based setting:

• The duration of the procedure was >240 minutes in 1032 (86%) procedures.

• Patients whose surgeries lasted <4 hours served as a control group for the lengthier procedures.

• The incidence of major morbidity was not increased in the patients undergoing procedures lasting >4 hours.

■ Clear, evidence-based criteria for the optimal duration of office-based surgery has not been established due to a paucity of objective level 1 evidence.9,28

■ In general, overall surgical procedure time should be <6 hours for outpatient surgery, especially in the office-based setting.9

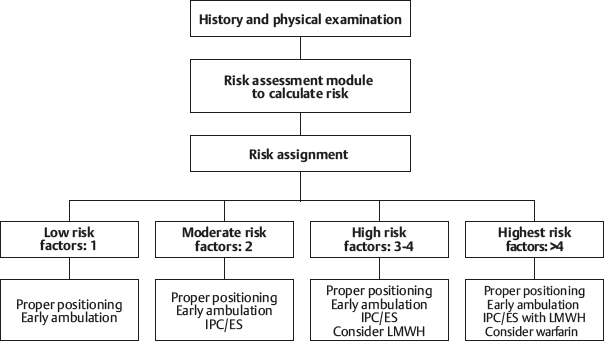

VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM (see also Chapter 11)

■ Incidence

• An ASPS study of existing data estimated that 18,000 cases/year of DVT may occur.37

• The overall incidence of DVT in the United States is 84-1550 per 100,000 per year.38

• The incidence of PE in the United States is 125,000-400,000 cases per year.39

• PE is the third most common cause of postsurgical mortality, accounting for approximately 150,000 deaths per year.

• The incidence of VTE varies greatly between medical and surgical specialties, as well as within a specialty, depending on the procedure performed40 (Table 9-3).

Table 9-3 Absolute Risk of DVT in Hospitalized Patients

| Group of Patients | DVT Occurrence (%) |

| Major general surgery | 15-40 |

| Major orthopedic surgery | 40-60 |

| Spinal cord injury | 60-80 |

| Multiple trauma | 40-80 |

| Neurosurgery | 15-40 |

| Stroke | 20-50 |

| Major gynecological surgery | 15-40 |

| Major urological surgery | 15-40 |

| Critical care patients | 10-80 |

| Medical patients | 10-20 |

■ McDevitt41 found that in patients undergoing elective surgery who received no prophylactic treatment the incidence of fatal PE was 0.1%-0.8%.

■ Medical comorbidities that may increase the incidence of VTE42,43:

1. Chronic venous insufficiency

2. Family history of thrombotic syndromes

3. Obesity

4. Trauma

5. Severe infection

6. Polycythemia

7. Central nervous system disease

8. Malignancy

9. Homocystinuria

10. History of pelvic or lower extremity radiation

11. Use of birth control pills

12. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT)

■ Obesity, use of birth control pills, and HRT are common within our aesthetic surgery patients.

■ Many body contouring surgeries are performed on patients who are trying to achieve improved appearance but may present at borderline obese BMIs or have previously been morbidly obese and underwent bariatric surgery, increasing their risk for VTE.

■ Most aesthetic surgery patients are female, and although there are limited data on the incidence of use of birth control pills or HRT within these distinct aesthetic surgery populations, most patients probably use these.

• A recent review and meta-analysis in the British Medical Journal of eight observational studies and nine randomized controlled trials showed a twofold to threefold increased risk of VTE in women on HRT.

► This study also established that the risk is highest within the first year of HRT use as well as for women who are considered higher risk for VTE.

► This review also established that transdermal HRT decreases the risk of VTE compared with the oral route of administration and appears to be safe in regard to thrombotic risk.44

• Men receiving estrogen therapy for prostate cancer are also at increased risk of VTE.

• Smoking compounds the VTE risk of patients who are taking oral contraceptives.

• The prothrombotic mechanism of estrogen is related to the decreased levels of protein S associated with elevated levels of circulating estrogen. Smoking exacerbates this clinical scenario.

• There are no definitive data to suggest when oral contraceptives or hormone replacement should be discontinued before surgery to minimize VTE risks, but it has been suggested that this should be done at least 2 weeks before surgery.42

■ Despite the recent interest in VTE prevention, evidence clearly establishing the true incidence of DVT and PE within the field of aesthetic surgery is insufficient.

• The earliest report on the incidence of VTE in the plastic surgery literature was in 1977 when Grazer and Goldwyn45 reported an incidence of DVT of 1.1% and PE of 0.8% in >10,000 abdominoplasty patients.

• Hester et al31 reported that combining abdominoplasty with another surgical procedure increased the incidence of PE.

• Voss et al reported a 6.6% incidence of PE when abdominoplasty was combined with intraabdominal gynecological procedures.46

• A survey study of board-certified plastic surgeons that reviewed 496,000 liposuction procedures and PE accounted for the largest percentage (23%) of deaths.26

• DVT and PE in large-volume liposuction procedures have been reported as ranging from 0%-1.1%.26,27,44

• When liposuction is combined with other procedures, the incidence of mortality increases from 1 in 47,415 to 1 in 7314, an almost sevenfold increase.27