Identifying new or changing melanocytic lesions, particularly in patients with numerous or atypical nevi, can be challenging. Total-body photography and sequential digital dermoscopy imaging, together known as digital follow-up, are 2 prominent forms of noninvasive imaging technology used in mole mapping that have been found to improve diagnostic accuracy, detect earlier-stage melanomas, and reduce costs. Digital follow-up, in combination with direct-to-consumer applications and teledermatology, is already revolutionizing the ways in which physicians and patients participate in melanoma surveillance and will likely continue to enhance early detection efforts.

Key points

- •

Detecting melanoma, particularly in patients with numerous or atypical nevi, can be challenging for even the most skilled dermatologists.

- •

Mole mapping involves using noninvasive imaging technology to enhance monitoring of new or changing melanocytic lesions.

- •

Total-body photography and sequential digital dermoscopy imaging, together known as digital follow-up, are 2 prominent forms of noninvasive imaging technology used in mole mapping.

- •

Noninvasive imaging technologies have been found to improve diagnostic accuracy, detect earlier-stage melanomas, and reduce costs.

- •

Total-body photography and sequential digital dermoscopy imaging, in combination with direct-to-consumer applications and teledermatology, are already revolutionizing the ways in which physicians and patients participate in melanoma surveillance and will likely continue to enhance early detection efforts.

Introduction

The incidence of cutaneous malignant melanoma is increasing at a rate faster than any of the other 5 most common cancers in the United States. Approximately 76,380 cases of melanoma and 10,130 deaths are expected in 2016. Because of the inverse relationship between primary tumor thickness and survival time, effective early detection of melanoma remains one of the most crucial strategies in improving patient prognosis. Dermatologists have traditionally screened for melanoma using a combination of clinical evaluation and dermoscopy (epiluminescence microscopy), which is more accurate in diagnosing melanoma than naked-eye examination. In patients with numerous or atypical nevi, it can be challenging for detecting new or changing lesions. Mole mapping incorporates photography into melanoma surveillance, making evaluation of multiple and suspicious lesions a more dynamic, objective, and precise process. Total-body photography (TBP) and sequential digital dermoscopy imaging (SDDI) are 2 prominent forms of noninvasive imaging technology used in mole mapping that have proved helpful in recognizing early-stage melanoma and minimizing benign lesion excisions.

Introduction

The incidence of cutaneous malignant melanoma is increasing at a rate faster than any of the other 5 most common cancers in the United States. Approximately 76,380 cases of melanoma and 10,130 deaths are expected in 2016. Because of the inverse relationship between primary tumor thickness and survival time, effective early detection of melanoma remains one of the most crucial strategies in improving patient prognosis. Dermatologists have traditionally screened for melanoma using a combination of clinical evaluation and dermoscopy (epiluminescence microscopy), which is more accurate in diagnosing melanoma than naked-eye examination. In patients with numerous or atypical nevi, it can be challenging for detecting new or changing lesions. Mole mapping incorporates photography into melanoma surveillance, making evaluation of multiple and suspicious lesions a more dynamic, objective, and precise process. Total-body photography (TBP) and sequential digital dermoscopy imaging (SDDI) are 2 prominent forms of noninvasive imaging technology used in mole mapping that have proved helpful in recognizing early-stage melanoma and minimizing benign lesion excisions.

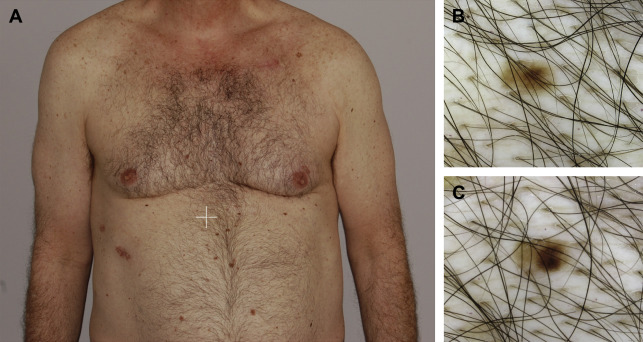

Noninvasive imaging technology categories

TBP is a series of approximately 25 images of the entire skin surface that can be used as an adjunct to total-body skin examinations (TBSE), patient self–skin examinations (SSE), and dermoscopy. Photographic documentation serves as a baseline comparison for future TBSEs and allows a physician or patient to detect new lesions and any naked-eye changes in preexisting lesions. Once new or changing lesions have been identified by TBP, dermoscopy and SDDI can be used to further examine a suspicious lesion.

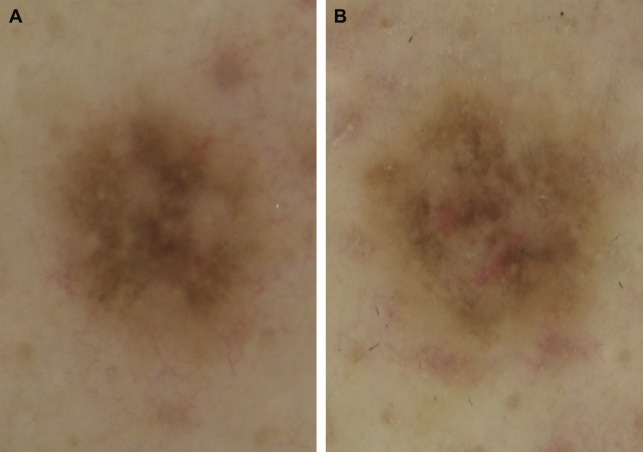

SDDI uses electronic storage of digital dermoscopic images to allow for side-by-side comparison of lesions over time. SDDI enables practitioners to detect changes in structure, color, and size. The electronic storage of digital dermoscopic images can be used for short-term or long-term monitoring. Most centers will use both lengths of follow-up in patients with numerous atypical lesions. Short-term monitoring (approximately 3 months) is useful for detecting subtle changes in a discrete suspicious lesion. This monitoring is typically reserved for flat or only superficially raised lesions that do not satisfy the classic surface microscopic criteria for the diagnosis of melanoma and either (1) have a recent history of change while exhibiting only minor clinical atypia or (2) are mildly to moderately atypical lesions without a history of change. At follow-up, lesions showing any morphologic change should be excised. Routine long-term monitoring (6–12 months) can be used in patients with numerous lesions thought to be clinically inconspicuous or with other high-risk phenotypes for developing primary melanoma. If asymmetrical enlargement, focal changes in pigmentation and structure, regression features, or change in color (appearance of new colors) are detected during long-term follow-up, excision should be considered. The threshold for excision is commonly determined not only by the morphologic appearance and number of lesions, but also by the patient’s skin cancer history, personal preferences, and compliance.

Digital follow-up (DFU) refers to the simultaneous implementation of TBP and SDDI ( Fig. 1 ). (For the remainder of this article, mole mapping will be referred to as DFU .) Although either TBP or SDDI can be used independently, the combination is superior to a single method alone and when used with SSEs, TBSEs, and dermoscopy, contributes important temporal information to the overall clinical assessment. Lesions with features suggestive of melanoma should undergo biopsy, whereas those with equivocal but not diagnostic features could undergo short-term SDDI.

Challenges in melanoma screening

Diagnosis of melanoma is often multifactorial and incorporates patient history, gross and dermoscopic appearance, comparison with neighboring lesions, and identification of change. Although change can be the key and even sole sign of a melanoma, not all new or changing lesions are melanomas. Malignant features are particularly difficult to discern during early stages of melanoma growth, when preventing morbidity and mortality is more likely. One study found that dermoscopists were able to correctly identify small melanomas with only an average diagnostic sensitivity of 39% and a specificity of 82% and recommended small melanomas for biopsy with a sensitivity of 71% and specificity of 49%. Distinguishing between small melanomas and small benign pigmented lesions was difficult for even expert practitioners.

Furthermore, emphasis on detection and subsequent biopsy of changing skin lesions can lead to overdiagnosis, particularly in patients at high risk or with multiple nevi. Benign-to-malignant ratios (the number of biopsies of benign lesions performed to make the diagnosis of one skin cancer) are a helpful measure of diagnostic accuracy. Although there is no clear benchmark, numerous studies have found benign-to-malignant biopsy ratios as low as 3:1 to 30:1 for practitioners using a simple clinical examination to serial photography and dermoscopy. The potential for associated harms, such as poor cosmetic results, and increased health care costs with overdiagnosis are real concerns, highlighting the importance of distinguishing truly potentially lethal lesions from those that are benign.

Value of digital follow-up

Noninvasive imaging technology helps dermatologists catch early-stage melanomas while improving diagnostic accuracy. As both stand-alone modalities and in combination, TBP and SDDI can confer specific clinical benefits.

TBP is particularly helpful in detecting changes in lesions that often do not follow the classic ABCDE (asymmetry, border irregularity, color variegation, diameter >6 mm, evolving) criteria. Feit and colleagues reported that 74% of melanomas detected in patients with TBP were a result of subtle changes that did not show classical clinical features at the time of detection. On the other hand, TBP can uniquely identify new lesions —in a study of patients with multiple atypical nevi who were undergoing TBP, two-thirds of melanomas detected arose de novo.

SDDI is useful as a second-level screening tool for evaluating lesions with borderline features. Using SDDI in these scenarios, physicians have the option of resorting to short-term follow-up, when they might have otherwise biopsied a lesion. SDDI also allows sensitive detection of the most relevant and often subtle microscopic changes associated with melanoma, such as the development of new focal or eccentric new structures, atypical vessels, regression features, or asymmetric enlargement ( Fig. 2 ).