A variety of surgical adjuncts can be added to upper eyelid blepharoplasty with the goal of enhancing surgical results and patient satisfaction. All of these procedures are minimally invasive and most are performed through a standard eyelid crease incision. These procedures can be added to stabilize or conservatively lift the outer brow, prevent the stigmata of postoperative volume loss, improve the brow-eyelid transition and contour, and reposition a prolapsed lacrimal gland. The procedures are generally straightforward, easily learned, and complication free. Familiarity with these techniques provides the aesthetic eyelid surgeon with added options to improve surgical results.

Key points

- •

Contemporary blepharoplasty surgery has undergone a paradigm shift which focuses on techniques that preserve volume.

- •

A browpexy is a minimally invasive, nonformal, temporal brow stabilization or conservative lift that can be performed in an external or internal fashion.

- •

The nasal fat pad of the upper eyelid is relatively stem cell–rich and tends to become clinically more prominent with age. This fat can be preserved and redistributed within and outside the eyelid/orbit during blepharoplasty.

- •

Lacrimal gland prolapse is a normal involutional change that can lead to temporal eyelid fullness. The gland be safely repositioned to its native location during blepharoplasty surgery.

- •

The brow fat pad can be elevated and supported during blepharoplasty surgery to potentially improve the eyebrow-eyelid transition and contour.

Introduction

Upper blepharoplasty is one of the most common facial aesthetic and functional procedures performed in the world today. It is one of the oldest described treatments of the aging face; initially elaborated on in ancient times by Albucasis in Spain, and Ali Ibn Isa in Baghdad. In these early reports, upper eyelid skin was grossly removed with cautery or pressure necrosis. Upper eyelid surgery was then largely forgotten until reemerging in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The procedure has evolved significantly into a technique that also addresses the orbicularis muscle and eyelid/orbital fat. In the 1950s, Costaneras enhanced our understanding of contemporary upper blepharoplasty surgery by publishing on a more advanced anatomic knowledge of the upper lid, including the various fat compartments. Flowers and Seigel popularized tissue excision techniques that led to a high crease, large tarsal platform, and a generally hollow upper sulcus. This subtractive form of surgery was in vogue until the early part of this century when a paradigm shift from surgery based on tissue excision to one in which tissue (ie, muscle and fat) is preserved developed. This shift is founded on the concept of recreating the fuller aesthetic of youth rather than the gaunt stigmata of the more traditional excision-based procedures.

This article reviews adjuncts to upper blepharoplasty that can be performed at the time of surgery to potentially enhance results. The techniques described are quick, minimally invasive, low-risk, and mostly focus on the concept of volume preservation. All procedures can be performed through the standard eyelid crease incision except for the external browpexy variant.

Introduction

Upper blepharoplasty is one of the most common facial aesthetic and functional procedures performed in the world today. It is one of the oldest described treatments of the aging face; initially elaborated on in ancient times by Albucasis in Spain, and Ali Ibn Isa in Baghdad. In these early reports, upper eyelid skin was grossly removed with cautery or pressure necrosis. Upper eyelid surgery was then largely forgotten until reemerging in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The procedure has evolved significantly into a technique that also addresses the orbicularis muscle and eyelid/orbital fat. In the 1950s, Costaneras enhanced our understanding of contemporary upper blepharoplasty surgery by publishing on a more advanced anatomic knowledge of the upper lid, including the various fat compartments. Flowers and Seigel popularized tissue excision techniques that led to a high crease, large tarsal platform, and a generally hollow upper sulcus. This subtractive form of surgery was in vogue until the early part of this century when a paradigm shift from surgery based on tissue excision to one in which tissue (ie, muscle and fat) is preserved developed. This shift is founded on the concept of recreating the fuller aesthetic of youth rather than the gaunt stigmata of the more traditional excision-based procedures.

This article reviews adjuncts to upper blepharoplasty that can be performed at the time of surgery to potentially enhance results. The techniques described are quick, minimally invasive, low-risk, and mostly focus on the concept of volume preservation. All procedures can be performed through the standard eyelid crease incision except for the external browpexy variant.

Internal and external browpexy

Contemporary upper blepharoplasty requires an evaluation and assessment of the eyebrow and upper lid as an aesthetic unit. Because temporal brow ptosis is a common aging change that can add to upper eyelid lid fullness, stabilizing or lifting the outer brow has become an essential adjunct to aesthetic upper blepharoplasty. Formal brow lifting procedures are invasive, costly, and potentially fraught with motor and sensory neurologic defects. A browpexy, or brow suture suspension, is not a formal lift. It is a measured anchoring of brow tissue (muscle and/or fat) to the periosteum of the frontal bone (or bone itself) above the superior orbital rim. Its purpose is to provide stabilization or a slight lift to the outer brow in a minimally invasive way to allow appropriate skin excision during blepharoplasty. It is typically added as an enhancement to blepharoplasty but also can be an isolated procedure.

The internal variant of the procedure was first described by McCord and Doxanas in 1990. In this original description, the subbrow tissue is accessed through a blepharoplasty eyelid crease incision and the brow fat pad is dissected free of the frontal periosteum for variable distances from the orbital rim. A guiding suture can be placed from skin to the internal wound to ensure the appropriate placement of the suspension suture on the undersurface of the brow soft tissue. The area of brow suspension to the frontal bone periosteum is measured directly. A 4-0 Prolene (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) or similar suture engages the periosteum at this location and also the internal brow tissue at the predetermined area (typically the inferior brow). Two to 3 similar sutures are placed laterally. When all sutures are tied, the brow is anchored to a new position.

Since its early description, there have been modifications of the procedure that have included extended dissection, release of deep retaining ligaments of the brow, extirpation of the temporal brow depressor muscle (lateral orbital orbicularis oculi), and the use of an external anchoring device fixated to the frontal bone (Endotine, Coapt Systems, Palo Alto, CA) ( Fig. 1 ). The main problem with all these procedures has been inconsistent results. Often no lift or stabilization was noted by surgeon or patient beyond a short-term result. This can be related to surgeon experience, technique, limitation of dissection, weakness of the procedure, or some combination thereof.

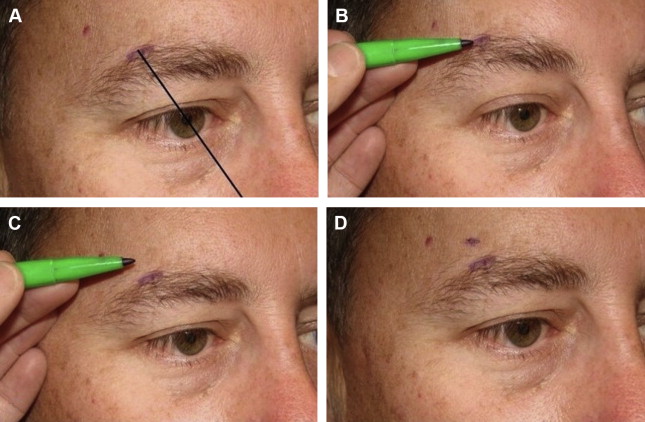

More recently, an external variant of this procedure has been described, which has been called the “External Browpexy”. In this variant, an 8 mm marking is made, tangential to the superior brow hairs or within the superior brow hairs, at the junction of the body and tail of the brow. The exact location is determined in the preoperative area with the patient in the sitting position. The authors’ preference has been to select an area at the superior brow that corresponds to a line drawn through the nasal ala and lateral limbus or pupil. The point is determined based on brow arch and lift desired, and can be modified depending on patient desires and gender. This area is elevated to the desired brow height. The marking pen is placed at this new height and the brow is allowed to return to its native position. A second mark is then made on the skin above the brow with the brow at this native position ( Fig. 2 ). The distance between the 2 marks is the amount of lift to be achieved.

The procedure begins with a punch incision made to the periosteum at the demarcated area at the superior brow hairs. Whereas the external incision is small, the internal dissection proceeds medially and laterally to the periosteum for 25 mm (3× external incision). The basis for this is that the skin incision is small to lessen potential scarring but the internal dissection is larger for more raw surface area and subsequent cicatrix to anchor the brow. The periosteum at the level of the elevated brow height is then engaged with a forceps and a 4-0 Prolene suture on a P-3 needle is secured to the periosteum at this location. The suture is then passed from below, through the brow fat pad and orbicularis muscle, and then redirected from above through orbicularis muscle and the brow fat pad and tied. An elevation and anterior rotation of the brow is achieved. In addition, brow fullness may be recreated because the brow fat elevates and rotates similarly. The wound is then closed in layers ( Figs. 3 and 4 , [CR] Part 1).

The senior author has performed this procedure on more than 100 patients during the last 4 years. The surgical results have been good, with rare minor and reversible complications. Specifically, there has been negligible scarring, no suture spitting or migration, no granulomas, and no infections or contour issues. A few patients have noted prolonged pain or tenderness over the brow suspension suture. These symptoms have resolved with time and/or serial injections of fluorouracil 50 mg/mL and/or Kenalog 5 mg/mL. The best measure of the potential for this procedure was noted in patients who presented with unilateral brow ptosis and had surgery only on that side to create symmetry. The authors have found a routine improvement in symmetry in these cases ( Fig. 5 ). A current ongoing study evaluating the results of this procedure has shown a mean brow elevation of 2.97 mm laterally and 1.90 mm centrally at an average 6 months follow-up. Granted, these are short-term results, but they are encouraging and more substantial than what the authors have experienced with the internal variant. The authors believe the external procedure yields more reliable results than the internal technique because

- 1.

There is lift from above rather than support from below

- 2.

The superior fixation prevents the brow from pivoting over the anchor point

- 3.

The orbicularis muscle and brow fat pad are anchored instead of just the fat pad

- 4.

Brow elevation and suture placement are more precisely measured

- 5.

The brow fat pad is elevated and anteriorly rotated, which may better volumetrically enhance the brow.

Of note, the idea for this procedure arose from observing patients who had traumatic full thickness (to bone) lacerations above the brow. It was observed that, in several of these patients, a localized peak (lift) in the brow developed after the wound healed. From this observation, the concept of a controlled suprabrow brow incision and fixation to bone developed. Overall, the authors have been pleased with this procedure. Whether there is long-term efficacy requires a more detailed study with serial standardized measurements of brow height over time. This is the next step in the continued evolution of the procedure. Most importantly, however, patients have been very satisfied with both the option of a noninvasive brow rejuvenation procedure and the surgical results.

Nasal fat preservation/translocation upper blepharoplasty

Hollowing of the upper eyelid and sulcus can occur as a normal consequence of aging or iatrogenically after traditional excisional (subtractive) blepharoplasty techniques. Overzealous removal of skin, muscle, and fat often results in a gaunt or skeletonized appearance after surgery that is in contrast to the more contemporary understanding of the youthful fullness, curves, contours, and smooth topographic transitions of the eyebrow–upper eyelid aesthetic unit. This volume-depleted appearance unmasks the orbital rim, depletes the upper sulcus, and may lead to an A-frame deformity. Although the general tissue debulking inherent to this form of surgery can initially create a lighter and less puffy eyelid, patients invariably develop the typical volume-deficient stigmata of traditional upper blepharoplasty. These sequelae can be addressed with secondary interventions such as fat transfer, grafts, and injectable fillers. However, appropriate preoperative evaluation and surgical planning may prevent these issues and the needed or secondary interventions.

Nasal fat pad translocation is a novel approach to upper blepharoplasty in which nasal upper eyelid/orbital fat is preserved and redistributed from areas of relative excess to areas of relative deficit. Such adjunctive fat pad preservation and translocation may lessen or prevent the volume-deficient results often seen with traditional surgery. Similar techniques in lower blepharoplasty have gained wide acceptance as a normal adjunct to surgery that may more adequately address the transition of the lower eyelid to the cheek and prevent the postoperative volume loss associated with standard fat excision procedures. Similar thinking, until recently, has lagged in regards to upper eyelid surgery. The authors have studied upper lid fat preservation techniques in detail and believe they are a better option to attaining the most appropriate long-term aesthetic surgical results.

The concept of preserving native upper eyelid fat in blepharoplasty surgery was not developed by the authors; it was modified from previously documented procedures. In 2010, Sozer and colleagues reported on transposition of the central (preaponeurotic) eyelid fat to the temporal eyelid to create lateral fullness. The authors have little experience with this procedure and cannot comment on its utility. However, because the central eyelid fat tends toward involution with age, there is concern that transposing this fat pedicle may advance central lid hollows and potential A-frame appearance. Park and colleagues reported on combined inferior transposition of the nasal and central eyelid fat pads from the level of Whitnall ligament to the inferior eyelid, in the particular subset of Asian patients. They termed this procedure orbital fat relocation and thought it added to the fuller appearance of eyelids in these patients. In both reports, the investigators reported no complications with excellent surgical results.

The authors have focused attention on isolated transposition of nasal eyelid fat during blepharoplasty. There is evidence of the utility of such thinking. The nasal fat pad of the upper lid is anatomically, structurally, and clinically different than the central eyelid fat. Nasal fat is whiter, denser, and continuous with deeper extraconal and intraconal orbital fat ( Fig. 6 ). This is in contrast to the central eyelid fat compartment. This fat is less dense, yellower, and separated from deeper orbital fat by the levator aponeurosis. Therefore, the central fat pad is referred to as preaponeurotic. This is also why nasal upper eyelid fat can be accessed transconjunctivally (there is no aponeurosis to potentially damage). The nasal fat pad has also been shown to be relatively stem cell–rich and to clinically tend toward prominence with age. Conversely, the central eyelid fat is relatively stem cell–poor and, typically, clinically involutes with age. These eyelid fat pad characteristics are the basis of isolating a nasal fat pedicle for transfer in blepharoplasty surgery. The goal is to transpose stem cell–rich and clinically prominent eyelid fat from areas of excess to areas of deficit.