The population of the United States is becoming increasingly more diverse as there is an ever expanding influx of various ethnic groups and races that comprise the general population. As a result, the singular concept of Nordic beauty that dominated the United States media throughout the middle of the twentieth century has given way to a more diverse multiracial aesthetic. There is also a growing trend in aesthetic surgery toward ethnic feature preservation and avoidance of a “westernized” look that was more popular in previous years. Today’s facial plastic surgeon must be familiar with these trends and aesthetic goals within this rapidly growing patient population. This article describes the anatomy of the Asian and Latino face and describes the techniques of midface alloplastic augmentation.

In recent years, the population of the United States has become more diverse as there is an ever expanding influx of various ethnic groups and races that comprise the general population. According to the US Census Bureau, the nation will be more racially and ethnically diverse, as well as older, by 2050. The non-Caucasian population is projected to be 235.7 million out of a total United States population of 439 million by mid century. Today, Asians make up 5% (15.3 million) of the United States population. This figure is expected to nearly double to 9% (39.5 million) by 2050. The Latino, or Mestizo population now comprises 15% of the population of the United States (45.9 million). By 2050, it is expected to increase to 30% of the population (131.7 million). As a result, the singular concept of Nordic beauty that dominated the United States media throughout the middle of the twentieth century has given way to a more diverse multiracial aesthetic, as championed in the entertainment industry, with the choice of multicultural fashion models that grace the runways and print media. In addition, there is a growing trend in aesthetic surgery toward ethnic feature preservation and avoidance of a “westernized” look that was more popular in previous years. Today’s facial plastic surgeon must be familiar with these trends and aesthetic goals within this rapidly growing patient population. This article describes the anatomy of the Asian and Latino face and describes the techniques of midface alloplastic augmentation.

There are various facial characteristics that present unique challenges in the Asian patient. A review of these characteristics will prove helpful to frame this discussion. Asian skin is thicker and contains greater collagen and pigmentation. The Asian face is also subjected to different gravitational and directional forces due to an overall wider midfacial skeletal structure, increased malar fat, and a weaker chin. The midface in Asian patients is typified by dense fat both superficial and deep to the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS). The combination of increased superficial fat and a thicker dermis lessens the incidence of superficial rhytids in Asian patients. The fat and fibrous connections between the SMAS and parotidomasseteric fascia decrease the amount of soft tissue ptosis in many Asians. For these reasons, the midface in Asians usually has minimal rhytids and a mild to moderate amount of ptosis as the patient ages. However, because of the dense attachments between the fascial layers, soft tissue surgical rejuvenation procedures usually do not provide as much soft tissue elevation in Asian patients.

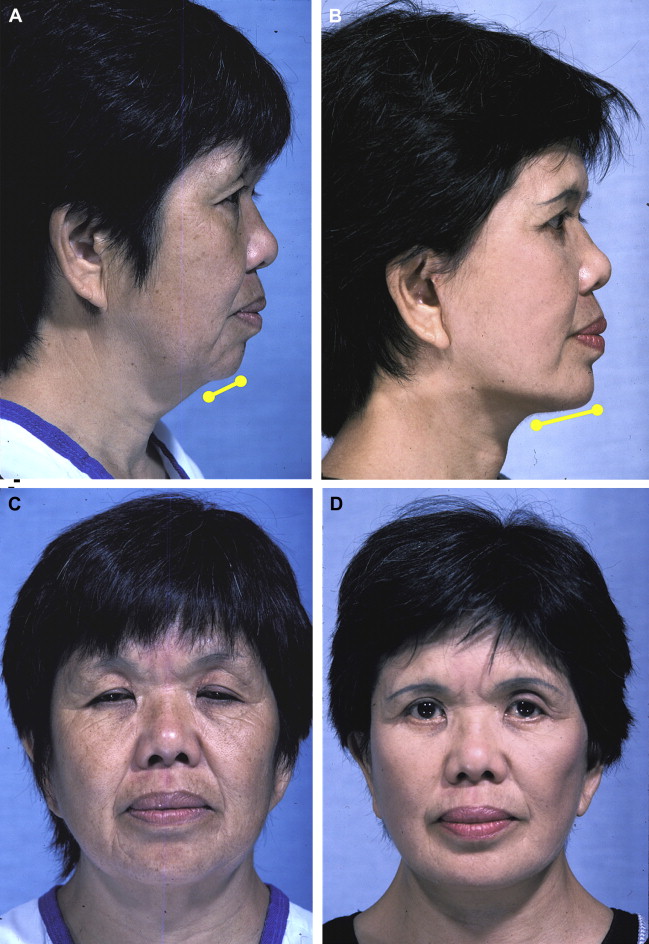

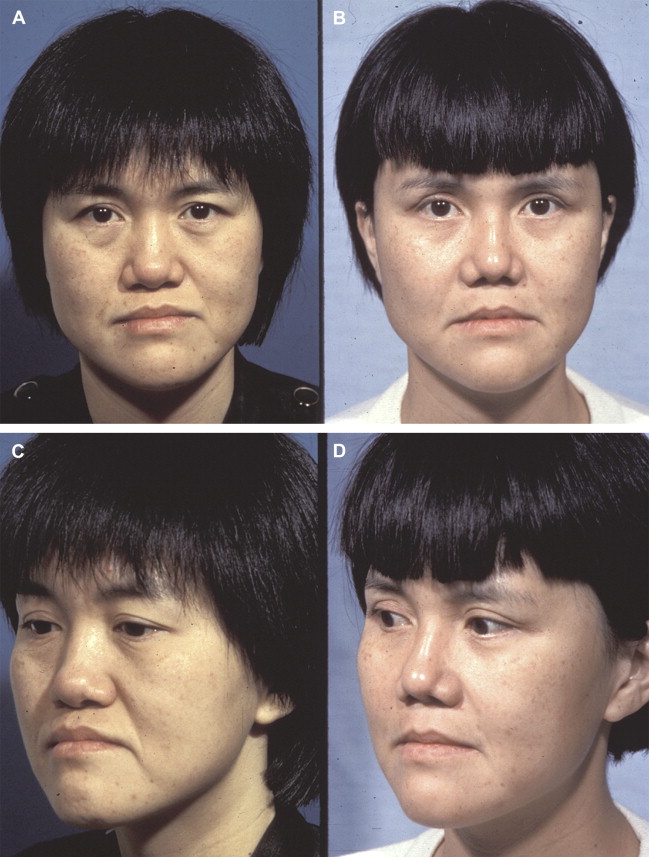

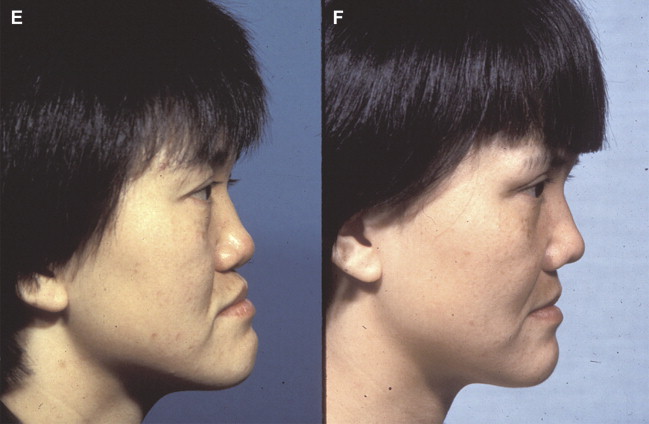

The typical facial skeleton in Asians has a strong and wide zygomaticomalar region. The bizygomatic width of these patients measures above average. The lower facial skeleton is often characterized by a weak chin in the anterior-posterior dimension, but the bimandibular width is usually wider in Asians than in Caucasians. In addition, the anterior-posterior distance between the mentum and hyoid bone is typically shorter than in Caucasians. Chin augmentation accordingly is often a useful adjunct to facial rejuvenation surgery in this population ( Fig. 1 ). The dental occlusion in Asians can have mild to moderate bimaxillary protrusion that causes the lower lip to be slightly protuberant, which often accentuates and exaggerates their microgenia. The position of the lower lip should therefore not be used as the only factor in judging ideal chin position. Chin augmentation should be performed conservatively, leaving the lower lip slightly protruding to maintain the ethnicity of the Asian face.

Skin incisions in Asians have a greater propensity toward hypertrophic and keloid scars, tend to remain erythematous for a longer period of time, turn hyperpigmented for an unacceptable length of time, or remain hypopigmented. Also, the Asian face tends to be wider and less angular than the Caucasian, similar to a toddler. Except for a portion of the Korean population, the midface tends to be shallower due in part to hypoplasia of the malar bone, with a lower nasal dorsum, fuller eyelids, and a more superficial orientation of the orbital rim. Cultural factors are important in this analysis as well. Prominent malar eminences, or “high cheek bones,” which are a celebrated feature of Caucasian women, are often construed as an unfavorable trait in this population. The excessively high malar eminences, found particularly in Koreans, are often considered masculine features and deemed unattractive within their culture.

Latinos, or Mestizos, who represent a mixture of European immigrants and the native populations of the Americas, have a strong mongoloid component in their facial features, and therefore have similar characteristics to Asians. Facial features of this ethnic group include thick sebaceous skin, abundant malar fat, prominent malar eminences, upper eyelid hooding, a broad face, a wide nasal dorsum, a platyrrhine or mesorrhine nose, a wide bigonial angle, and a protrusion of the dental arches that project the upper lip anteriorly resulting in an acute nasolabial angle. It should be noted that these are rough generalizations regarding the various races and ethnic groups. Given the extensive interracial mingling in our society, there are various subpopulations within these broad categories.

The use of facial implants began in the 1950s with various primitive cheek and chin implants. Since then, there have been advances in materials, shapes of implants, surgical techniques and, perhaps most importantly, the understanding of the role of volume and skeletal structure in the aging process. The facial skeleton and its corresponding soft tissue form the architecture of the face and neck. Facial implants augment the soft tissue and skeletal framework by replacing volume lost during the aging process, supporting soft tissue and elevating it to a more youthful position. Binder’s innovations in the 1980s established midface augmentation with malar/submalar implants as an independent and powerful method for midface rejuvenation by helping restore lost midfacial volume.

During the aging process, there are several characteristic changes in the midface. There is a loss of skin elasticity, soft tissue volume depletion, descent of soft tissue, and a diminution of the dental and skeletal support of the soft tissue envelope. As the malar, buccal, temporal, and infraorbital fat pads atrophy and lose their facial support, these areas become progressively ptotic secondary to gravity. The nasolabial folds become exaggerated, and the infraorbital rim becomes exposed. In conjunction with deepening of the nasolabial and nasojugal folds, submalar hollowness and cavitary depressions occur. These changes initially flatten the midface, which leads to exposure of the underlying bony anatomy creating an aged, fatigued appearance. By elevating, supporting, and replacing lost midface volume, midface implant techniques underscore the notion that the face can be rejuvenated successfully not only via “lifting” procedures but also through the augmentation of the soft tissue and skeletal foundation. Alloplastic midface augmentation is especially helpful in the Asian and Latino populations, who as a result of the aging process acquire more significant flattening of the midface, and thus become an ideal group for anterior projection and support of the premaxillary and submalar area.

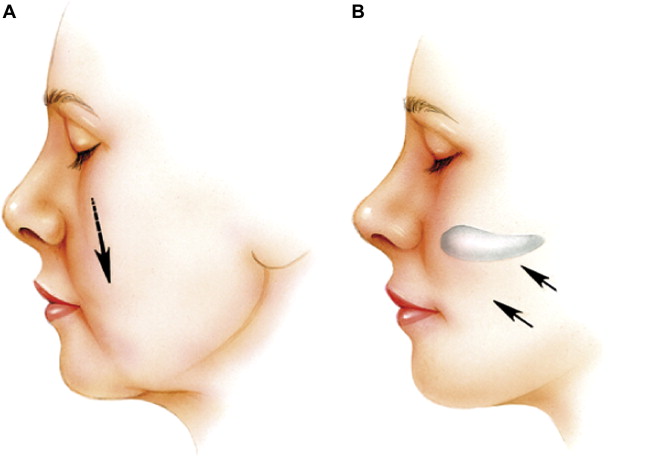

From a technical point of view, midface augmentation using alloplastic implants is straightforward and bears relatively few risks. The implantation is reversible and may be combined with standard rhytidectomy techniques. The aesthetic benefit is consistent, predictable, and lasting. Midface implants can replace lost volume, reduce midface laxity, and decrease the depth of the nasolabial folds ( Fig. 2 ). Submalar augmentation, performed in isolation, can provide a moderate amount of midfacial rejuvenation in middle-aged patients (age 35 to 45 years) who show early signs of facial aging and atrophy but lack the soft tissue laxity of extensive jowling or deep neck rhytids.

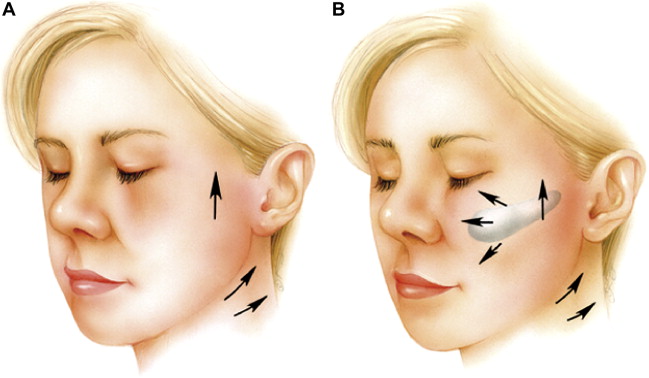

When combined with rhytidectomy, midface alloplastic augmentation can either sharpen or soften angles and depressions of the aging face, which can lead to a more natural look. The implants allow the skin and soft tissue to be draped over a broader, well-defined area after midface augmentation of the bony scaffold ( Fig. 3 ). In addition, if placed before facelifting, midface implants reduce lateral traction forces on the oral commissure, which also prevents an unnatural “overoperated” appearance. Finally, undermining of the midface periosteum during implant placement releases the deep attachments of the SMAS to the facial skeleton, thereby allowing greater mobilization and suspension of the ptotic soft tissues. The implant therefore acts as a spacer and prevents rapid reattachment of the periosteum, which keeps the midfacial soft tissues in an elevated and augmented position. As a result, midface alloplastic augmentation can significantly enhance and prolong the cosmetic outcomes of subperiosteal, sub-SMAS, and deep plane rhytidectomy ( Fig. 4 ).

Midface augmentation can thus achieve dramatic aesthetic results not achievable through soft tissue suspension techniques alone. Furthermore, many patients with prominent malar skeletons (as in the Asian population) but inadequate submalar soft tissue will benefit from volumetric enhancement of the midface inferior to the prominent zygomatic process. Also, patients having midface augmentation with concomitant revision rhytidectomy will benefit from having decreased downward vertical forces on the lower eyelid. Other procedures such as deep plane facelifting and subperiosteal facelifting can provide viable alternatives to midface alloplasts; however, if problems with volume loss and loss of facial shape are not addressed, the face may appear skeletonized, especially in those with very prominent bone structure and thin skin.

Injectable soft tissue fillers and fat transfer offer another option for improving midfacial aesthetics. However, the most important difference between fillers and midfacial implants is that implants not only provide support and volume to ptotic soft tissue, they also allow for a fixed 3-dimensional quality to the face and support of the soft tissues that volumetric filling alone cannot achieve. Fillers in the midface in large amounts can migrate laterally and result in an amorphous, overfilled, and unnatural look.

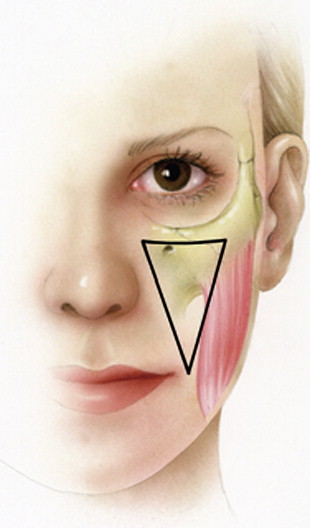

A key anatomic region in the midface is the submalar triangle, which is bordered superiorly by the zygomatic prominence, medially by the nasolabial fold, and laterally by the masseter muscle. This anatomic area represents the most common site of volume loss in the aging midface, especially in Asians and Latinos, but can be corrected readily with alloplastic implants ( Fig. 5 ).

Preoperative analysis

Preparing for midfacial alloplastic augmentation begins with a thorough history and physical examination followed by digital photographs and optional digital computer imaging. The computer imaging can help the patient identify the exact nature of their concerns and potential benefits of surgery. It is also important to analyze the entire upper and lower face and neck. Basal photos and apical bird’s eye views are especially helpful in identifying midface pathology and can help in selecting midface implants. Preoperative analysis and discussion of soft tissue and skeletal asymmetries is imperative both to prevent exaggeration of these effects postoperatively and to avoid unrealistic patient expectations.

Selecting the appropriate midfacial implant requires an ability to recognize the characteristics of midface deformity ( Table 1 ). Ideal evaluation requires separate analyses of the bony malar area and the soft tissue component of the submalar region. Patients exhibiting type I deformity with primary malar hypoplasia and adequate midface soft tissue are best suited for malar shell implants that cover the zygoma and continguous areas. These implants yield an arched appearance and project the cheek laterally. Fine edges gradually blend into the adjacent tissues to avoid abrupt changes in the facial architecture.

| Type | Description of Deformity | Augmentation Required | Implant Type to Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | Primary malar hypoplasia: malar boney deficiency with adequate soft tissue. Face lacks desirable features of angular, well-defined cheeks | Requires primarily lateral projection of the malar eminence; results in high-arched, laterally projected cheeks | Malar implant: shell-type extends into the submalar space for more natural result |

| Type 2 | Submalar deficiency; soft tissue deficiency with adequate malar bone. Face appears dull and flat; most common deficiency of the aging face | Requires anterior projection of the midface and submalar hollow; restores lost midface volume characteristic of a more youthful face | Submalar implant: placed over the anterior maxilla and the masseter tendon, extending into the submalar space |

| Type 3 | Combined malar and submalar deficiency: volume-deficient face with inadequate bony and soft tissues. Marked by premature signs of aging | Requires both anterior and lateral projection of the entire midface and submalar regions | Combined malar-submalar implant: lateral (malar) and anterior (submalar) projection to fill a large midfacial void |

The most common deformity of the aging face, especially in Asians and Latinos, is a type II submalar deficiency. This deformity is characterized by normal malar skeletal structure and soft tissue atrophy of the midface. Volume loss and inferior descent of the midface soft tissues leaves an excavated, flattened appearance. Submalar implants are the implants of choice for patients with this deformity.

Type III deficiency is characterized by both a malar and submalar deficiency. The effects of aging are exaggerated in these patients, because they have poor skeletal support that facilitates soft tissue descent toward the nasolabial folds and oral commissure. Combined malar-submalar implants are the treatment of choice for patients with a type III deficiency. Most of these patients will do poorly with a rhytidectomy alone because of this lack of bony support for the suspended soft tissues. Hence, the result of rhytidectomy in these patients without alloplastic augmentation is usually suboptimal and transient at best. In addition, some patients with premaxillary retrusion may require custom implants using computer-aided design (CAD) and manufacturing (CAM) techniques that use a high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scan of the face ( Fig. 6 ).

Surgical technique

General Guidelines

Available biomaterials for midface augmentation include silicone, polytetrafluoroethylene (Medpor, Porex Surgical Products, Newnan, GA, USA), and expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE). The authors prefer silicone implants because of their flexibility, low infection rates, and ease of insertion and removal. Despite the occasional use of the subciliary and lateral facelift approach for implant placement, the transoral approach placing the implant in a subperiosteal pocket offers the most advantages. This approach facilitates an easy insertion and direct visualization of all midface anatomic structures, in particular the infraorbital nerve and inferomedially, the submalar space. There is also the advantage of avoiding external scars, and prevention of the potential downward traction on the lower eyelid postoperatively if a subciliary approach is used. The process of capsular fibrosis facilitates tight adherence of the silicone implants to the facial skeleton in the subperiosteal plane, which protects against postoperative implant migration. However, a potential disadvantage of the transoral approach is the risk of contamination and wound infection due to the implant’s exposure to oral flora. Hence, meticulous surgical technique is of paramount importance.

The type of facial deformity may determine the sequence of procedures when performing alloplastic augmentation and rhytidectomy concurrently. Type I and III patients who require a major malar component to their midface augmentation procedure or have significant facial asymmetry should have their implants performed before the rhytidectomy. This action allows the surgeon to visualize and thus compensate for the structural changes that may not be apparent after facial edema occurs. In this case, the wound is either left open until the end of the rhytidectomy, or a Penrose drain is placed into the oral incisions to prevent the formation of fluid collections. For most Asian or Latino patients, who require only submalar soft tissue augmentation because of a type II deformity, the operator can perform the rhytidectomy before placement of the implant. In this case, the advantages include the ability to maintain a dry implant pocket, reduction of subperiosteal bleeding, and the capability of closing the intraoral incision immediately following augmentation to reduce the risk of infection. In either situation, local anesthetic is infiltrated into the tissues in a similar manner as if the implant procedure were performed alone.

Preparation for Surgery

Antibiotic prophylaxis with a broad-spectrum oral antibiotic is started 1 day preoperatively. In the holding area, the patient sits upright, and the crucial areas designated for augmentation are clearly marked ( Fig. 7 ). The marked areas should illustrate the midfacial volume deficit, areas of depression, infraorbital nerve axis, and the malar eminence. As a general guide, the most medial border of the typical midface implant may be readily identified by marking the position of the infraorbital nerve, which is parallel to the midpupillary line with the patient staring straight ahead. Then the patient should smile widely to assist in determining the most inferomedial position of the implant and thus ensure that there is no interference with the facial mimetic function. The markings should outline the areas of maximal depression that will receive the maximal augmentation. Once the skin is marked, the patient should be shown a mirror to allow he or she to concur that the proposed changes are satisfactory. Of importance is that the markings may vary to some degree from the ultimate placement of the implant, and should not be the sole determining factor for implant placement.

Intravenous antibiotics and steroids are used routinely intraoperatively. After the patient has received adequate anesthesia, whether via general anesthesia or intravenous sedation, the surgeon injects 1% or 0.5% lidocaine with epinephrine into the gingival-buccal sulcus and the midface in the subperiosteal plane. To aid in the even dispersion of the local anesthesia and minimize contour irregularities due to injectate overaccumulation, hyaluronidase (Wydase, Wyeth-Ayerst, Philadelphia, PA, USA) is added to the anesthetic solution and the face is then massaged. The operative site is prepared with povidone-iodine (Betadine, Purdue Frederick, Norwalk, CT, USA) from soaked gauze sponges inserted into the gingival-buccal sulcus at the level of the canine fossa for 10 minutes.

Incision and Dissection of the Malar Eminence

Due to the plasticity of the mucosa, insertion of the implant requires only a 3-mm stab incision in the gingival-buccal sulcus over the lateral canine fossa and maxillary buttress ( Fig. 8 ). The incision is made in an upward oblique direction, and is carried immediately and directly to the maxillary bone. Bleeding is minimized by compressing the mucosa against the bone. An inferior cuff of mucosa of a minimum of 1 cm facilitates closure at the end of the procedure. Removing dentures during the operation is unnecessary, because they do not interfere with insertion of the implant, and actually direct placement of the incision above the denture to the correct location.

After the initial incision, the periosteum of the anterior maxilla is elevated superiorly and laterally ( Figs. 9 and 10 ). Following the preoperative markings, the surgeon uses his or her external free hand to provide crucial guidance to the direction and extent of dissection. The subperiosteal elevation is initiated with the Joseph elevator, which is changed quickly to a broader 10-mm Tessier elevator ( Fig. 11 ). This technique enables a greater degree of safety and ease of periosteal dissection. The infraorbital nerve should be identified carefully if the proposed implant is large or bears a significant medial component. This identification prevents placing the implant over the foramen.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree