Chapter 52 Microvascular technique of composite tissue transfer

![]() Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

Introduction

On the other hand, severe burn patients, to whom the free flap transfers are often adapted, are characterized by a shortage of available donor tissue for flap elevation. In addition, one of the major drawbacks of the conventional free flap is the bulk of the tissue. The technique of tissue expansion first introduced in the early 1980s1,2 can reduce the donor site morbidity and the bulkiness of the flaps. In burn patients, this technique has been well indicated for alopecic deformities of the scalp. Moreover, it can extend the indication of the free flap transfer for severe burn patients.3–5

Prefabricated flap is another versatile reconstructive option, especially in patients with severe burn injuries. In this method, a vascular carrier is implanted to a new skin territory. Following a period of maturation and neovascularization, the prefabricated flap can be transferred, based on the implanted pedicle. Washio6 reported the very first attempt of prefabricated flap in a canine model using an intestinal seromuscular patch as the vascular carrier. Thereafter, various types of tissue, such as muscle,7 fascia,8 and vascular pedicle alone, have been developed for the same purpose. In severe burn patients, the limited donor site for free flap elevation can be maximized using these techniques.

Usage of the microvascular technique for acute burn care

Because the thermal injury induces the damage primarily to the skin surface, the necessity of microvascular technique is quite rare for acute burn care. The majority of burn patients require only debridement and coverage with split-thickness skin grafts. The exceptional situation necessitating the microvascular technique is the extremely deep burn involving underlying structures such as bone, tendon, major vessels and internal organs. These local conditions cannot support skin grafts for coverage. Historically, these wounds were managed with preservation of eschar in expectation of generating granulation tissue or decortication of bone cortex to prepare a bed for skin grafts.9 These techniques often led to long-term morbidity, including extensive necrosis of underlying structures, persistent skin ulceration and resultant infections. Therefore, microvascular free tissue transfer should be considered as a primary method of reconstruction for extremely deep thermal injury whenever clinically feasible (Fig. 52.1). These reconstructive techniques offer an early, reliable means of definitive reconstruction, preserving function, providing uncomplicated healing, and promoting early rehabilitation.10,11

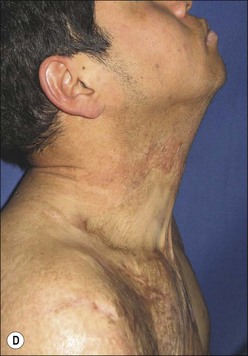

Free flap to the post-burn neck contracture

Thermal injuries to the anterior neck region are prone to induce a severe contracture, especially in a case with flame burn, because the skin of this area is relatively thin and pliable. The optimal reconstructive method for skin supplementation, namely skin grafting versus flap coverage, is still controversial. The flap coverage takes advantage regarding pliability of the reconstructed skin, not necessitating a long-term splinting, which is mandatory after skin grafting to the anterior neck region. However, the primary shortcomings of conventional free flaps have been their bulkiness and the unavoidability of a secondary defatting procedure. To obtain a natural neck appearance, particularly the mentocervical angle, thinning of the flap is essential for achieving an aesthetically satisfactory result. A large number of thin free flaps have been developed for anterior neck reconstruction.12–14 These flaps with a thin layer of fat not only without deep fascia and fat but also without much of the superficial layer, are well suited for this purpose. Dense vascular network located in the subdermal layer can provide reliable vascularity in relatively large flaps, leaving the suprafascial axial vessels skeletonized from surrounding fat tissue.

The groin flap is the oldest free flap, which is considered to have minimum donor site morbidity. In 1972, McGregor and Jackson15 first described the vascular basis of the groin flap, based on the superficial circumflex iliac vessels, and introduced the concept of axial blood supply. The following year, Daniel and Taylor16 reported the first microvascular transfer of groin skin. Harii and Ohmori17,18 later described in detail the vascular supply based on 87 clinical dissections. Historically, its acceptance had fallen out of favor due to massive adipose tissue around a short pedicle vessel, and the development of a plethora of new flaps. However, the versatility of this old flap has been revisited when the above-mentioned thinning technique is applied.12,19 Because the groin region is often left intact even in severe burn patients, the thin groin flap is a good candidate for severe post-burn neck reconstruction (Fig. 52.2). The advantages of this flap are as follows: (1) flaps can be thinned radically, which obviates a secondary defatting procedure; (2) the repositioning is not required for flap elevation; (3) for flap widths of up to 12 cm, donor sites are closed primarily12; (4) donor-site scars are well hidden and no functional deficit results; (5) a natural neck contour including a sharp mentocervical angle can be achieved; (6) the postoperative tendency to form disfiguring lateral scar bands is reduced.