Fig. 23.1

Classification of lymphoscintigraphy images of the lower limbs. (a) Type I. There are obvious regional lymph nodes and no dermal backflow. (b) Type II. Dermal backflow (arrow) in the thigh is visible. (c) Type III. Dermal backflow can be seen in both the thigh and leg (arrows). (d) Type IV. Dermal backflow is visible in the leg (arrow). (e) Type V. Dermal backflow remains at the ankle and foot (arrow)

In secondary obstructive lymphedema, types II, III, and IV lymphoscintigraphic images are good indications for lymphatic–venous anastomosis, because superficial collecting lymph vessels can be easily found in the affected limb and it is relatively easy to anastomose the lymph vessels and veins together due to dilatation of the lymph vessels. In type V images, it is sometimes difficult to identify the lymph vessels because lymph fluid does not flow sufficiently. Patients with type I lymphoscintigraphic images may only require observation for a while, because their clinical symptoms are not as advanced, although the lymph vessels in the affected limb of such patients may already be dilated to some degree because of mild stenosis of the lymphatics at a proximal site.

Primary lymphedema is also an indication for lymphatic–venous anastomosis if the patient has Type I, II, III, and IV lymphographic images, although it is difficult to identify suitable lymphatics in cases with hypoplasia of the lymphatic system.

Near-infrared ICG fluorescence lymphography has recently been introduced for real time imaging of the lymphatic system [13, 14]. The equipment for this diagnostic modality is compact and easy to handle. Classification of the severity of lymphedema based on fluorescence lymphographic images has been reported [15]. Visualization of linear patterns on images enables easy determination of functional lymph vessels, but if the patient has thick skin or fibrous subcutaneous tissue, locating functional vessels by lymphography is not easy.

SPECT-CT lymphoscintigraphy has the potential to determine the indications for surgery and predict the sites of lymph vessels that are difficult to find by ICG fluorescence lymphography or plain lymphoscintigraphy (Fig. 23.2a) [16–18]. Recently, SPECT-CT has been used preoperatively, because locations of the lymph vessels can be detected precisely even in the thigh area (Fig. 23.2b). In the figure, the green, yellow, and red marks indicate stasis of lymph and the lymphatics in the subcutaneous, intermuscular, and perivascular layers of the thigh to lower leg.

Fig. 23.2

SPECT-CT lymphoscintigraphy in secondary lymphedema in a 50-year-old woman. Secondary lymphedema of the right lower limb. (a) Clinical photo and plain lymphoscintigraphy of a patient with secondary lymphedema of the right leg. Lymphoscintigraphy demonstrated type III images. (b) SPECT-CT images in the same patient. Green, yellow, and red marks indicate stasis of lymph and the lymphatics in the subcutaneous, inter-muscular and perivascular layers of the thigh to lower leg

Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography may also be useful in detecting lymphatic vessels. This technique has been reported by several authors for sentinel lymph node biopsy [19–21]. This diagnostic modality can visualize lymph vessels and lymph flow in real time and identify the locations of lymph vessels even in the thigh area where ICG fluorescence lymphography cannot easily identify vessels in severe cases (Fig. 23.3).

Fig. 23.3

Contrast-enhanced and non-contrast enhanced ultrasonography on the medial side of the leg in secondary lymphedema. (a) Longitudinal sections in contrast-enhanced (left) and non-contrast enhanced modes (right). (b) Axial sections in contrast-enhanced (left) and non-contrast enhanced modes (right). Courtesy of Dr. Shinobu Matsubara

Contraindications

A recent attack of dermato-lymphangio-adenitis (DLA) is a contraindication for lymphatic–venous anastomosis, which should only be performed more than 3 months after DLA. In such cases, fatty tissue around the lymphatic vessels adheres to the lymphatics, which, according to my clinical experience, makes them difficult to find. Patients with lymphatic hypoplasia should also not undergo lymphatic–venous anastomosis because suitable lymphatics can rarely be detected. Patients with venous diseases, such as deep vein thrombosis or severe varicose veins of more than C2 severity according to the CEAP classification [22] are not indicated for anastomosis, because venous pressure in the leg is probably higher than that in the lymphatics in such patients. Although Huang [23] reported the relationship between the pressure in the lymphatic vessels and veins, attention should be paid to the presence of venous diseases before attempting lymphatic–venous anastomosis.

Preoperative Treatment

Preoperative Complex Decongestive Physiotherapy (CDP)

O’Brien reported a percentage decrease in volume after lymphatic–venous anastomosis of 36 % in patients with preoperative CDP and 29 % in those without preoperative CDP [7]. Hence, his report did not clearly highlight the importance of CDP.

If preoperative CDP is not applied appropriately to patients with lymphedema, the presence of a significant amount of interstitial fluid in the subcutaneous layer of the affected limb makes it difficult to locate the superficial lymph vessels for anastomosis. The presence of thinner subcutaneous tissue facilitates the detection of functional lymph vessels by ICG fluorescence lymphography. Hence, the purpose of preoperative CPD is to prepare the surgical site and to create the best possible conditions for surgery by drainage of the excess interstitial fluid, thus, also leading the patient toward the maintenance phase [24]. The duration for which preoperative CDP is performed depends on the severity of edema and compliance of the patient [25], ranging from a few months to half a year.

Procedures

Equipment

An operating microscope is essential for performing lymphatic microsurgery. Since the outer diameters of the targeted lymphatic vessels mainly range from 0.25 to 0.5 mm in Japanese female patients, in my experience, magnification of 20–25 times is required for anastomosis. For dissection in the subcutaneous layer, micro-scissors and mosquito forceps with fine tips are useful. A micro-knife, forceps with 0.1 mm tips, and scissors with small blades are needed for cutting, and suturing of vessels is performed with 11-0 suture and an 80 μ needle.

Anesthesia

General anesthesia is the preferred anesthesia method during surgical anastomosis in a thick subcutaneous layer and when many anastomoses need to be performed in many parts of the affected limb. On the other hand, local anesthesia is preferable if few anastomoses are planned in the upper extremity, the lower leg, or the dorsum of the foot.

Position

In most cases of lower limb lymphedema, the anastomosis can be performed in the supine position. However, if the lymphatic vessels along the short saphenous vein are targeted, the prone position is preferable. If suitable lymph vessels and veins for anastomosis are present in the medial thigh, the knee of the affected side should be bent at about 90°, together with abduction of the hip. Vessels in the thigh can be anastomosed with the surgeon sitting on the affected side of the patient while using a microscope.

Locating the Sites for Anastomosis

Two dyes, ICG and Patent Blue, are injected into the dermal and subdermal tissue of the interdigital spaces. Five percent Patent Blue is useful for visualization of the lymph vessels in the surgical field. If the skin of the patient is not very thick and darkly colored, ICG fluorescence lymphography using a near-infrared camera system is helpful to pinpoint the sites for anastomosis, because lymph vessels can be detected as linear fluorescence and the subcutaneous veins as black lines due to nonfluorescence. The areas where linear fluorescence and black lines cross each other are determined as the sites for anastomosis. However, we sometimes encounter cases in which we cannot detect the subcutaneous veins by the camera system. In such cases, we shortlist one or two sites for anastomosis on each lymph vessel.

Detection of Suitable Lymphatic Vessels

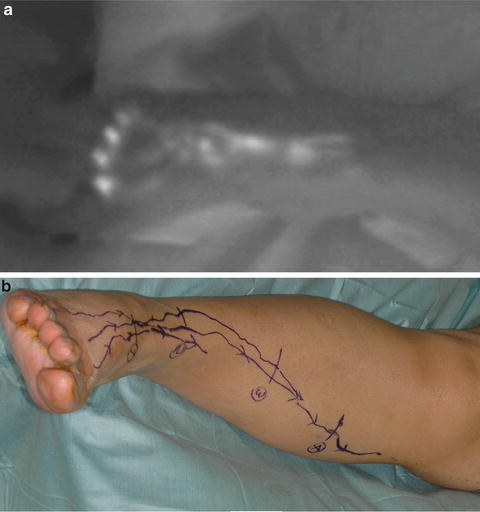

As mentioned above, ICG fluorescence lymphography, which uses the near-infrared camera system, makes suitable lymphatics visible through the skin in the surgical field as linear fluorescence (Fig. 23.4a) [13, 14]. However, using this method, lymphatics cannot be detected in the thigh area or in cases with thickened skin, because the maximum depth that near-infrared rays can reach is between 1 and 2 cm. Lines can be marked on the skin along the linear fluorescence, to highlight the lymphatics (Fig. 23.4b).

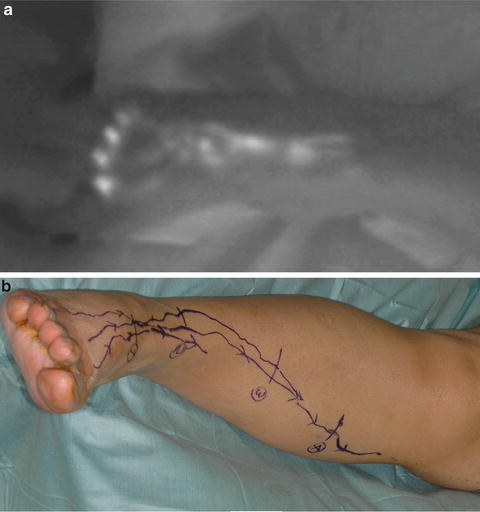

Fig. 23.4

Preoperative ICG fluorescence lymphography. (a) Linear fluorescence on the dorsum of the foot. (b) Markings on the skin along the lines

Selection of Suitable Veins

As mentioned above, subcutaneous veins for lymphatic–venous anastomosis are identified as black lines during ICG fluorescence lymphography. Selection of the veins for anastomosis is quite important for obtaining good patency. In cases with breast cancer-related lymphedema, intravenous infusion of an anticancer agent on the affected arm as preoperative chemotherapy may damage the subcutaneous vein. The integrity of the vein can be confirmed by washing out of saline through the vein using a syringe with a fine plastic needle.

From a technical point of view, veins with an outer diameter of 1–2 times that of the lymphatic vessel are suitable for anastomosis. Further, it is essential that the vein be sufficiently mobilized by dissection to reach the lymphatic vessel without tension and torsion, to ensure easy passage of lymph through the anastomosis.

Anastomosis

Skin incisions 2–3 cm in length are made at each selected anastomotic site (Fig. 23.5). The subcutaneous fat layer is carefully dissected with mosquito forceps with fine tips (Fig. 23.6a). A vessel loop (blue) is introduced beneath the lymph vessel to stretch the wall of the lymphatic vessel (Fig. 23.6b, c). For side-to-end anastomosis, the side of the lymphatic vessel is incised with a micro-knife (Fig. 23.6d). When the tip of the knife reaches the lumen of the lymphatic vessel, lymph flows out through the incision. The length of the incision on the lymphatic vessel should be shorter than the outer diameter of the vein (Fig. 23.6e). Stents (6-0 nylon stitch of 3 mm length) are inserted to secure the lumen of the lymph vessel (Fig. 23.6f) [26, 27]. The first stitch should be placed at the left edge of the incision and appropriate stitches are placed according to the size of the vein (Fig. 23.6g–k). Another stent should be inserted to the lymph vessels to secure to put the stitches at the other end. So, two stents are usually required for anastomosis. If the outer diameter of the venous end is less than 0.3 mm, another stent should be inserted into the venous end to secure the anastomosis. Three stents are required totally. These stents are removed from the vein and lymph vessel at the end of anastomosis.

Fig. 23.5

Skin incisions for anastomosis in the lower limb

Fig. 23.6

Operative steps of lymphatic–venous side-to-end anastomosis

Confirmation of Patency

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree