32 Lower Urinary Tract Infection

EPIDEMIOLOGY

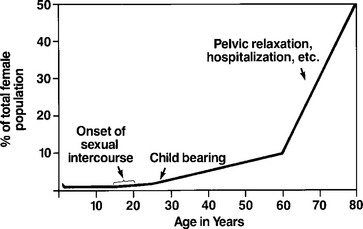

The prevalence of urinary tract infections increases with age. At 1 year, 1% to 2% of female infants demonstrate bacteriuria. In this age group, there is a direct correlation between cystitis and upper urinary tract infection. As many as 50% of these patients demonstrate abnormalities on intravenous pyelograms, such as scarring, ipsilateral reflux, or some obstructive disease. After 1 year of age, the infection rate decreases to approximately 1% and remains low until puberty. Between ages 15 and 24, the prevalence of bacteriuria is about 2% to 3% and increases to about 15% at age 60, 20% after age 65, and 25% to 50% after age 80 (Fig. 32-1). Sexual activity and pregnancy are major factors in younger age groups, whereas pelvic relaxation, systemic illnesses, and hospitalization play major roles in older women. However, the prevalence of underlying urologic abnormalities decreases dramatically with age.

Figure 32-1 Prevalence of bacteriuria in females as a function of age.

(From Karram MM: Lower urinary tract infection. In Ostergard DR, Bent AE, eds: Urogynecology and urodynamics, Baltimore, 1991, Williams & Wilkins.)

Approximately 2% of all patients admitted to a hospital acquire a urinary tract infection, which accounts for 500,000 nosocomial infections per year. One percent of all these infections become life threatening. Instrumentation or catheterization of the urinary tract is a precipitating factor in at least 80% of these infections. The annual cost of nosocomial urinary tract infections is estimated to range between $424 and $451 million. Asymptomatic bacteriuria occurs in 2% to 8% of adult females, the likelihood of which increases with increasing age, diabetes mellitus, and a history of symptomatic urinary tract infection. Symptomatic urinary tract infections are believed to affect over 30% of women between the ages of 20 and 40 years. Patients who develop infections are more likely to develop subsequent infections. The incidence of re-infections seems to be independent of whether an infection was treated or allowed to resolve on its own. It has been shown that the probability of recurrent urinary tract infections increases with the number of previous infections and decreases with greater amount of elapsed time between infections. Rates of reinfection seem to be independent of bladder dysfunction, evidence of chronic pyelonephritis on radiologic examinations, and vesicoureteral reflux. Kraft and Stamey (1977) showed that patients who had two or more urinary tract infections within a 6-month period had a 66% probability of attaining another infection in the next 6 months. Antimicrobial prophylaxis of urinary tract infections does not change the risk of recurrent bacteriuria, but only seems to alter the time until the redevelopment of another urinary tract infection.

PATHOGENESIS

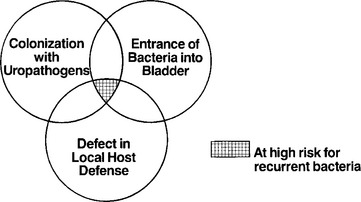

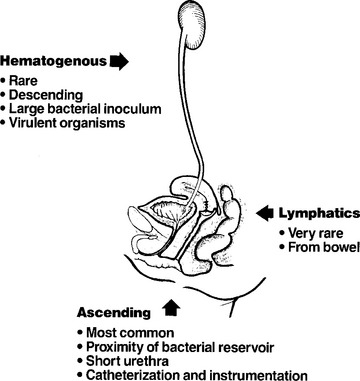

Although the normal female urinary tract is remarkably resistant to infection, certain risk factors for developing urinary tract infections have been identified (Box 32-1). The majority of urinary tract infections are ascending infections wherein the fecal flora initially colonize the vaginal introitus, then the periurethral tissues, and eventually gain entry into the bladder (Fig. 32-2). The development of urinary tract infection requires the interaction of appropriate host susceptibility and pathogen virulence factors (Fig. 32-3).

BOX 32-1 KNOWN RISK FACTORS FOR URINARY TRACT INFECTION

Figure 32-2 Pathways of bacterial entry into the urinary tract.

(From Karram MM: Lower urinary tract infection. In Ostergard DR, Bent AE, eds: Urogynecology and urodynamics, Baltimore, 1991, Williams & Wilkins.)

DEFINITIONS

DIAGNOSIS

Urine Microscopy

Microscopic examination of urine adds valuable information to the diagnosis and evaluation of urinary tract disorders. A thorough microscopic examination of an uncentrifuged sample of urine can detect the presence of significant bacteria, leukocytes, and red blood cells. In a random urine sample, pyuria is defined as more than 10 white blood cells/mL of urine and is assessed using a hemocytometer. In a clinical setting with symptoms suggestive of urinary tract infection, pyuria and hematuria offer sufficient supportive evidence to warrant empirical antibiotic therapy. In the absence of pyuria, the diagnosis of urinary tract infection should be questioned. Some examples of abacterial or sterile pyuria are tuberculosis, renal calculi, glomerulonephritis, interstitial cystitis, and chlamydial urethritis.