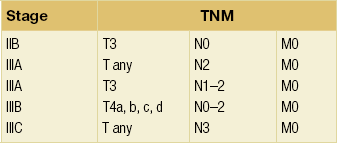

13 Locally advanced breast cancer (Fig. 13.1) includes primary breast tumours with diameters of greater than 5 cm, breast cancers with frank skin or chest wall involvement, and any size of tumour with certain degrees of nodal involvement, but excludes cancers that have spread further than local, supra/infraclavicular and internal mammary chain nodes.1 Locally advanced breast cancer includes all cancers of ‘TNM’ stage III, but also a subset of stage II cancers (Table 13.1). The definition of locally advanced breast cancer includes inflammatory breast cancer (Fig. 13.2), which is characterised by involvement of the dermal lymphatic vessels by cancer cells that produces an inflamed, erythematous appearance to the whole breast. The management of locally advanced breast cancer should be multidisciplinary in nature, and based on the extent of the disease, as assessed with computed tomography (CT) scanning of chest, abdomen and pelvis, and, if required, isotope bone scanning, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or positron emission tomography (PET) to detect or confirm metastatic disease (Chapter 1). Histological confirmation of the tumour type along with appropriate immunohistochemistry for oestrogen receptor and human epidermal growth factor (HER-2) receptor (supplemented by fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) analysis of HER-2 status) is required before embarking on therapy (Chapter 2). Multimodal therapy is generally needed and the timing and nature of treatments will vary depending on whether the disease is confined to operable areas, whether there is involvement of internal mammary or supraclavicular lymph nodes, and above all the general fitness of the patient. Figure 13.2 Inflammatory breast cancer demonstrating skin erythema (with indrawn nipple and skin tethering) and a visible axillary nodal mass. Pathological confirmation of the clinical diagnosis of locally advanced breast cancer should be made by core biopsy to distinguish invasive breast cancer from ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or metastatic disease to the breast from another primary site. If the patient is likely to be a candidate for neoadjuvant therapy, placement of a radiological marker in the tumour immediately following the core biopsy is required to facilitate accurate surgical resection or to localise the site of the cancer for the pathologist if mastectomy is subsequently performed.2 However, on occasion, excision of a skin nodule under local anaesthetic may be useful to confirm the diagnosis and get tissue for receptor analysis. Resectional surgery aims to secure clear surgical margins around the cancer. There is a balance between the completeness of excision (margin involvement is linked to recurrence) versus poorer cosmetic results from more extensive surgery. If the cancer is not excisable by conventional means then neoadjuvant therapy or radiotherapy are the only treatment options. Radical mastectomy (including excision of pectoralis major and level III axillary clearance) does not improve survival over total mastectomy (odds ratio of death 0.98 over 10 years3) and is rarely, if ever, indicated even in locally advanced breast cancer. Since survival following breast conservation is not significantly different from that following mastectomy, this has led most centres to use neoadjuvant therapy for locally advanced breast cancer as initial treatment followed by surgery, including the option of breast conservation where appropriate. Where neoadjuvant therapy has produced an excellent clinical and radiological response, effective surgery is possible only if a surgical marker was inserted prior to commencing neoadjuvant treatment, as the tumour may not be visible radiologically. As for all breast conservation surgery (Chapter 4), complete surgical excision with clear margins of at least 1 mm on pathology review is required to reduce disease recurrence. The term ‘toilet mastectomy’ has historically been applied to mastectomy performed to excise locally advanced breast cancer. Surgery alone rarely controls such cancers and combination with radiotherapy and/or systemic therapy is now standard. Excision of bulky disease in the breast previously led to difficulties in skin closure with the need for split-skin grafting or application of an omental flap to the chest wall but the widespread use of skin-bearing autologous flaps, particularly the latissimus dorsi flap, has made primary closure possible in all but a few patients. Previously, level III axillary node clearance was the axillary surgery of choice in patients with locally advanced breast cancer due to the high probability of axillary lymph node involvement. Given the significant morbidity associated with level III axillary clearance, for patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy who were node negative at diagnosis or have a good clinical response this is being challenged. Sentinel lymph node biopsy of the post-treatment axilla is now being used to guide therapy and is of similar efficacy to that in patients who have not received neoadjuvant therapy4 (see Chapter 7). Although some advocate sentinel node biopsy prior to neoadjuvant therapy this is illogical and denies those whose nodes are cleared by this treatment the option of sentinel node biopsy after completion of their systemic therapy. It is useful, however, to consider sentinel node biopsy prior to a definitive surgical procedure in patients who are having mastectomy and undergoing breast reconstruction, in order to guide the extent of the axillary node dissection. Axillary nodes are converted to node negative in approximately 35% of patients by neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The rate of conversion from positive to negative relates to tumour type. Between 25% and 50% of involved nodes in triple negative cancers, 40–60% in HER-2-positive patients who receive trastuzumab but less than 10% of nodes in patients with oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancers are converted from positive to negative. For those patients undergoing mastectomy either as primary treatment or following neoadjuvant therapy, there remains controversy regarding immediate breast reconstruction (Chapter 9). Although there may be concerns that delayed wound healing (on the chest wall or at donor sites for autologous reconstruction) may delay the delivery of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy or postoperative radiotherapy5 and the need to avoid radiotherapy following reconstruction with prostheses, few patients experience significant delays. Some surgeons do not offer immediate reconstruction to patients with locally advanced disease because of the likelihood postoperative radiotherapy will be required. Over the past 15 years, US practice has swung from immediate reconstruction for patients with locally advanced breast cancer to a more conservative approach of delayed breast reconstruction. There is the option for patients wishing reconstruction of a skin-sparing mastectomy and placement of a tissue expander that is deflated during radiotherapy and reflated shortly after completion of radiation. Thereafter, an autologous reconstruction with a myocutaneous flap utilises the preserved skin. Autologous abdominal flap reconstruction at the time of mastectomy has been reported by some to produce unsatisfactory long-term outcomes following radiotherapy, and with modern postoperative radiotherapy techniques in the UK it does not appear to prejudice the cosmetic outcome nor the oncological management.6 Radiotherapy is thought to work mainly by causing damage to the DNA of tumour cells, which is repaired more slowly than the damage caused in the adjacent normal tissue. Tumour tissue is therefore preferentially destroyed compared with the normal tissue over a course of radiotherapy treatment. In general, the chance of tumour control increases with increasing total dose of radiotherapy given, but so does the chance of permanent radiotherapy-related side-effects, some of which have been implicated in treatment-related mortality7 (Box 13.1). Certain tissues (termed ‘late-responding tissues’) such as nerves and, to some extent, lung can withstand a higher total dose of radiotherapy without giving rise to symptomatic damage if the dose of each separate radiotherapy treatment (or ‘fraction’) is kept low. Traditionally, a course of radiotherapy that was thought to give the best chance of long-term tumour control comprised a relatively large total dose given over several weeks by using small daily fractions. Whilst shorter palliative courses of treatment may be considered for less fit patients, the total dose has to be reduced to minimise the toxicity of the treatment, because the fraction size for such short courses is by necessity large.8 The reduction in the total radiotherapy dose for such short courses often means that any benefit obtained from radiotherapy is short-lived and may not be worth the inconvenience to the patient of the treatment, and so many oncologists advocate longer courses over several weeks for advanced breast cancer. This view is being challenged, partly because of the results of large randomised radiotherapy studies such as the START trial,9 which has demonstrated that shorter, ‘hypofractionated’ regimens using a lower total dose than has been traditional produce good outcome results with a trend towards fewer side-effects. It remains to be seen whether further research into much shorter hypofractionated courses yields similar results. When treating locally advanced breast cancer, whatever surgery is performed on the breast, postoperative radiotherapy significantly reduces locoregional recurrence and improves overall survival for both premenopausal10 and postmenopausal11 women, and modern techniques do not have the cardiac morbidity of older treatments.12 Postoperative radiotherapy (which may be given after adjuvant chemotherapy) reduces local recurrence from 35% without radiotherapy to 8% with radiotherapy and improves disease-free survival at 10 years from 24% to 36%. Radiotherapy following the surgical treatment of locally advanced breast cancer is given in the same way as treatments for early breast cancer, the aim being to reduce local relapse by about two-thirds and improve survival.13 Locally advanced breast cancer, by definition, has many features that predict for local relapse (large tumour size, lymph node involvement, close or positive margins despite adequate surgery). Thus, postoperative radiotherapy is usually given,14 even if there has been a good response to neoadjuvant treatment, as the risk of local relapse in larger tumours is higher than for less advanced cancers.15 The chest wall or residual conserved breast is treated and the peripheral lymphatics are irradiated as appropriate16 (see Chapter 15). It is unusual to irradiate the internal mammary chain nodes, as evidence for the efficacy of this treatment is lacking, although much of the data relates to trials that are decades old.17 If the patient is not fit for or declines surgery, and is fit for radiotherapy, then radiotherapy may be used as the principal local treatment. It is unusual to ‘cure’ a locally advanced breast cancer without surgery, but sometimes excellent local control can be obtained (Figs 13.3 and 13.4) and unpleasant symptoms of the tumour, such as pain, discharge, bleeding and odour, can be partially or completely removed following radiotherapy treatment.

Locally advanced breast cancer

Introduction

Surgical management

Axillary surgery

Breast reconstruction in locally advanced breast cancer

Radiotherapy

Adjuvant (postoperative) radiotherapy

Primary radical radiotherapy

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Locally advanced breast cancer