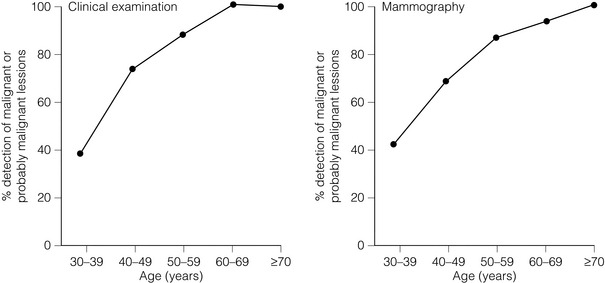

18 Litigation for clinical negligence has accelerated at an alarming rate. In 2009/10 the NHS paid out £787 m (including £164 m for defence and claimant legal costs).1 In the USA, the value of malpractice claims for delay in the diagnosis of breast cancer 15 years ago was second only to that for neurological damage to neonates2,3 and today this situation remains unchanged.4 Poor cosmetic outcome is also a frequent cause for litigation and heightened public awareness has increased patients’ expectations of recompense for real or perceived injury following both cosmetic and reconstructive breast surgery. The legal process differs between countries and although this chapter is based on civil law in England and Wales, the general principles in use elsewhere are similar.5 For a claimant to succeed in law, she must satisfy the court (in the UK a judge, or in some countries a jury) that there was a failure or breach of duty of care (liability) and that as a foreseeable result she suffered an injury (causation). For the case to succeed, the court must find in favour of the claimant with regard both to liability and to causation. Clinical negligence cases are heard in civil court and the judge determines on the balance of probabilities whether the defendant is liable. This is entirely different from a criminal court determining guilt or innocence where the level of proof is beyond all reasonable doubt (which many equate to a degree of confidence > 95%). If the court finds in favour of the claimant, the court awards financial recompense to redress, as far as money is able, the injury that she has suffered. Any doctor – GP, radiologist, surgeon or pathologist – owes each individual patient a duty of care. This is rarely an issue. In the NHS the doctor acts as an employee of the hospital or health board, which is covered by the NHS Litigation Authority, which administers a scheme that acts as a mutual insurer for participating trusts (Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts).6 When acting in a private capacity, the doctor is covered by a professional defence organisation of his or her choice. A doctor is not negligent if he or she acts in accordance with a practice accepted at the time as proper by a responsible body of medical opinion. The Bolam test arises from the case of a patient who received electroconvulsive therapy and sustained fractures.7 Negligence was alleged because the patient was not given muscle relaxants and was inadequately restrained. Some doctors would have used muscle relaxants and restraints, others not. The doctor was not found negligent because he acted in accordance with a practice accepted at the time, even though other doctors may have advocated a different practice. The Bolitho modification of Bolam adds the requirement that for the practice or opinion formed to be acceptable, it must be based on logical argument; an irrational practice cannot be argued as reasonable in court simply because a body of medical opinion agrees with its use.8 National and local guidelines of good clinical practice are now in use throughout the NHS with guidelines covering patient referral, diagnosis, treatment and organisational arrangements within breast units.9,10 Breaches of guidelines are not indicative of, or equivalent to, negligent practice and guidelines are constantly being amended in the light of scientific knowledge, healthcare resources, government targets, etc. Consideration must always be given to the time at which the alleged breach of duty took place and for a guideline to be relevant it must have been in the public domain at the time. Clinical practice that complies with guidelines is inevitably much easier to defend against allegations of negligence. A diagnostic excision biopsy exceeding 20 g, as set out in NHS Breast Screening Programme guidelines, does not equate to negligent practice; however, a patient claiming excessive deformity after such a procedure is unlikely to succeed in litigation if her biopsy specimen weighed under 20 g. There is ongoing debate regarding the medico-legal implications of surgical guidelines.11 Carrick et al.12 reported that whereas 41% of surgeons surveyed believed that guidelines would protect them against litigation, 37% believed that they would increase their exposure to claims. Doctors have been made increasingly aware of the need to warn patients of the risks involved with any diagnostic or therapeutic procedure, to involve patients in decision-making and to seek fully informed consent. Patient information leaflets, involvement of breast-care nurses and more detailed consent forms signed by the operating surgeon are now standard practice but have done little to stem the tide of litigation as expectations continue to rise. Consent obtained by a junior doctor without the knowledge and skill to undertake the intended procedure or to discuss the possible complications is no longer considered acceptable. The degree of disclosure is primarily a matter of clinical judgment, but major complications (such as loss of a flap in breast reconstruction) must be included even if their occurrence is rare.5,13 Where a procedure (such as breast reduction) is being undertaken primarily for cosmetic reasons, the surgeon is advised to include even minor potential consequences in the documentation of informed consent. The sole remedy available to the successful claimant is an award of damages – a sum of money intended to restore the claimant to the position she would have been in but for the negligent act. Explanation and apology to the claimant or her family, desirable though they may be, are not within the power of civil law, nor are recommendations for retraining, suspension or deregistration of doctors who find themselves as defendants. Patients seeking to hold their doctor to account are, however, increasingly turning to the fitness to practice procedures of the General Medical Council (GMC), with such enquiries rising 30% between 2004 and 2009.14 An unhappy patient may both embark on litigation and report the doctor to the GMC, with the practitioner facing so-called double jeopardy. In English law the perceived culpability or magnitude of the negligent act has no bearing on the sum awarded. This contrasts with the position in the USA, where cases that proceed to trial (the minority) rely on jury decisions that often incorporate an element of punitive or exemplary damages, a sum the jury considers warranted by the wrongfulness of the defendant’s act. The extent to which this affects the size of the award can be seen by comparing the average value of claims concluded by settlement ($282 000) with that secured by jury verdict ($870 000).3 In a review of the UK civil justice system, Lord Woolf singled out clinical negligence cases15 because the difficulty in proving both liability and causation accounts for much of the excessive cost and the high proportion of cases that fail. The root of the problem, however, lies less in the complexity of the law than in the climate of defensiveness. The patient’s disappointment when treatment goes wrong is heightened by what she perceives to be a refusal to acknowledge fault and an attempt to cover up. • Pre-litigation protocol where claimants should notify defendants with a written intention to sue 3 months before action. If liability is disputed, defendants should provide a reasoned answer. • Lists on the Queen’s Bench to include a list of judges familiar with clinical negligence cases and training of trial judges in medical issues. • Fast-track options for claims under £10 000 so that these can be litigated on a modest budget with a single expert acceptable to both parties appointed by the court. • The medical expert is now required to address his report to the court and not to the instructing party,16 with an overriding duty ‘to provide objective unbiased opinion to the court on matters within his expertise, never assuming the role of an advocate’. In civil litigation the court determines the facts, which means that the judge makes a decision on the balance of probabilities. This means that the successful claimant will normally recover damages in full, although in one case where the claimant was held to have lost an 80% chance of cure, a deputy high court judge directed that damages should be calculated accordingly.17 The all-or-none nature in awarding damages is arguably the most troubling aspect for experts involved in clinical negligence.18 For example, if the court finds that as a result of negligence a woman has suffered a reduction in her chance of survival from 60% to 40%, she will be awarded the full amount to compensate her (or her family) as though the loss had already occurred, on the basis that on balance she is now more likely to die. If the court finds, however, that her chance of survival has reduced from 90% to 60%, it may award her nothing on the basis that on balance her chance of survival remains unchanged. Delay in diagnosis may occur as a result of failure to refer the patient from primary care or, once referral has taken place, for example with false-negative mammography, failure to perform triple assessment, misinterpretation of equivocal results or the misfiling of a positive test result.19 Litigation arising from delay in diagnosis concerns two main areas: • Did the delay necessitate more extensive treatment? • Did the delay in diagnosis reduce the chance of cure? This is a controversial area since there is public expectation, promoted over the years by health campaigners, that earlier diagnosis offers better chance of a cure. Where expert opinion is divided, the court often prefers the evidence in favour of the delay having caused a reduced survival time. A review of claims for diagnostic delay in breast cancer in Sweden over a 10-year period concluded that delays had an impact on treatment in 23% of cases and adversely affected prognosis in 11% of those patients for whom the delay was longer than 12 months.20 The GP who sees many cases with benign breast symptoms each year but only one or two breast cancers is in a difficult position and GPs are increasingly facing litigation for delays in referral. The main area of contention is where long-standing or recurrent breast nodularity coexists with an (initially) undetected lump. Relying on a negative mammogram without an expert clinical examination, ultrasound or needle biopsy may increase the risk of false reassurance.19 GPs today are therefore faced with referring most women with breast symptoms for a specialist opinion and referral guidelines have been in use in the UK since 1995.21–23 Breast units throughout the UK submit audit data on compliance with 2-week target referrals for suspected cancers.24 The prioritisation of referral letters can be counter-productive if non-urgent cases have to wait longer, but current NHS guidelines stipulate all symptomatic breast referrals are now seen within 2 weeks. NHS ‘31/62’ cancer targets (allowing 31 days from urgent referral to diagnosis and 62 days to commencing treatment) will identify units in breach of national guidelines. The role of triple assessment, and the circumstances in which it fails, are critical. The specialist centre is also faced with the problem that women under 35 form the majority of the diagnostic workload (66%) but the fewest number of breast cancers (3%).21 Two studies commissioned by the Physician Insurers Association of America (PIAA)2,3 showed delay in the diagnosis of breast cancer to be the commonest cause of clinical litigation, and a striking feature of both studies was young age: women under 50 accounted for 69% of claimants and received 84% of the damages paid, whereas only 25% of cancers occur in women under 50. The most common reasons cited for the delay were (in descending order): • physical findings failed to impress; • failure to follow up the patient; • negative mammogram report or misreading of the mammogram; In 487 cases where liability was admitted, the mean delay was 14 months. The mean payout was $301 000, with higher damages for longer delays and to younger patients.3 Triple assessment is the foundation upon which clinicians diagnose breast lumps. However, the extent to which the accuracy of these tests is reduced in younger women is not well appreciated (Fig. 18.1). It has been suggested that perfection of diagnosis will require removal of every solid mass,25 but this would represent a retrograde step. The practice of defensive medicine, in place of conventional wisdom, may well be encouraged by a litigious public and diagnostic tests where the sensitivity falls below 95%. Figure 18.1 Sensitivity of clinical and mammographic examination by age. Reproduced from Dixon JM, Mansel RE. Symptoms, assessment and guidelines for referral. In: Dixon JM (ed.) ABC of breast diseases, 2nd edn. London: BMJ Books, 2000; p. 6. With permission from Wiley Publishing Ltd. About 70% of all breast cancers are palpable, but with tumours of 0.6–1 cm diameter this figure falls to 50%.26 The larger the breast and the greater the density of breast tissue, the more difficult physical examination becomes. Cyclical changes in breast parenchyma may require repeat examination at different phases of the menstrual cycle. Coexisting benign lumps, scars and distortion from previous surgery, the ridge of tissue above the inframammary fold, changes during pregnancy and lactation, and the underlying ribs all add to the uncertainty of clinical examination. Other difficulties include: inflammatory cancers masquerading as infection; the presence of implants with an associated fibrous capsule; and the effect of hormone replacement therapy, which increases the density of breast parenchyma both clinically and radiologically. The sensitivity of clinical examination in women aged 30–39 can be as low as 25%.26 A sensitivity over 90% can only be expected in older women, when the atrophic nature of the breast parenchyma and the low incidence of benign disease combine to make clinical diagnosis a relatively simple task. The low sensitivity of clinical examination, coupled with the low incidence of breast cancer and the considerable numbers of young women attending breast clinics, must largely explain why failure of physical findings to impress the clinician was one of the most common reasons for delay in diagnosis in the PIAA study.3 False-negative mammography is one of the principal reasons for delay in diagnosis,3,27 since it gives the clinician and patient false reassurance. Age is an important factor in false-negative reporting (Fig. 18.1), with the number of cancers missed inversely proportional to age: 36% of cancers in women aged 40 compared with just 9% in those aged 75. The net result of medicolegal pressure on breast radiologists has been an increase in recall and biopsy rates.28,29 The use of ultrasound is now an integral part of breast imaging in a patient of any age with a lump (see Chapter 1), especially when an abnormality is not detectable on clinical or mammographic examination. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy has replaced fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) in screen-detected tumours, although both techniques are currently acceptable in the symptomatic clinic. The expertise required for ultrasound examination and guided core biopsy has placed breast imaging outside the competency of the general radiologist. The breast surgeon using ultrasound in the clinic may be similarly compromised unless training in the technique can be verified.

Litigation in breast surgery

Introduction

Basic principles

Breach of duty

The Bolam test

Guidelines

Consent

The award of damages

The Woolf report

The burden (level) of proof

Delay in the diagnosis of breast cancer

Delay in primary care

Delay after specialist referral

The North American experience

Diagnosis of breast cancer

Physical examination

Mammography

Ultrasound

Litigation in breast surgery