Lichen Sclerosus: Introduction

|

Lichen sclerosus (LS) is a chronic inflammatory dermatosis of the anogenital area that affects quality of life due to the severe itching. LS may also present with extragenital manifestations that are generally nonpruritic. Of note, vulvar disease seems to have an increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma, but the role of additional cofactors (e.g., human papillomavirus infection or prior radiotherapy) has not been defined.

Epidemiology

The incidence of LS has not been precisely determined. It has been estimated to be in the order of 14 per 100,000 persons per year.1 LS is more prevalent in females, accounting for a 5:1 gender ratio. It preferentially affects women in the fifth or sixth decade of life and children younger than the age of 10 years.1,2 Up to 15% of LS cases occur in children, particularly in girls, and one study reported a prevalence of 1 in 900 premenarchal girls.3 A 0.07% incidence in males has recently been determined in a study of 153,432 male soldiers.4 Among blacks and Hispanics, the incidence in this group was 1.06%, whereas the incidence was only 0.051% in white soldiers.4 LS seems to be a prominent cause of phimosis; in one study, 14% of adolescent boys had LS, whereas 40% of phimosis cases in adult men were associated with LS.5 Similarly, a recent study of foreskins examined after therapeutic circumcision for phimosis confirmed many cases of unrecognized LS.6 As genital LS in males is almost exclusively seen in uncircumcised men, the rate of circumcision in a given population has a strong impact on the occurrence of the disease.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

The cause of LS is unknown. While a genetic predisposition has generally not been found,7 a recent observational cohort study reported a high rate of familial LS cases.8 Of 1,052 females with LS, 126 (12%) had a positive family history of LS. Vulvar cancer was significantly increased in those patients with a family history of LS compared with those without (4.1% vs. 1.2%).8 This report proposes a likely genetic component in the etiology of LS. Evidence for the presumed infectious cause, such as acid-fast rods, spirochetes, or Borrelia, has not been found.7 Serologic and clinical evidence of thyroid disease, alopecia areata, pernicious anemia, and vitiligo suggested an association with LS. Extragenital LS is commonly seen in association with plaque-type morphea, and some authors have suggested a common pathomechanism. Recently, low-titer autoantibodies against the extracellular matrix protein-1 (ECM-1) and collagen XVII have been identified in 67% of LS.9,10 ECM-1 (see Chapter 137) may be involved in basement membrane and interstitial collagenous fiber assembly and growth-factor binding,11 and may also regulate blood vessel function.12 In addition, antibodies to the basement membrane protein bp180 have been detected in childhood vulval LS lesions in four of nine children analyzed.13 All antibodies were IgG-type. There was no clinical and family history of autoimmune diseases or autoantibodies in the children studied. Local irritation also seems to play a role in some cases. The disturbed function of fibroblasts with increased production of collagen has been demonstrated in LS.14,15

Clinical Findings

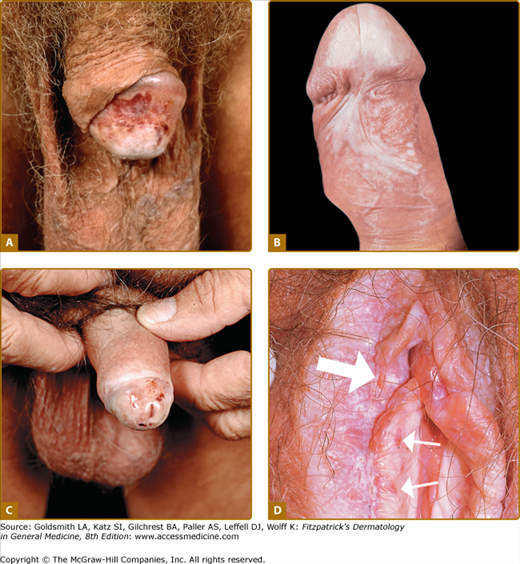

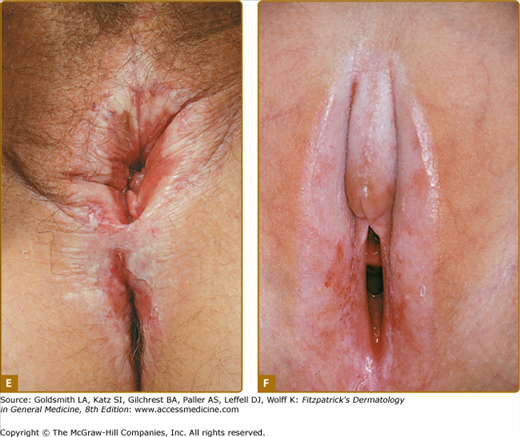

Polygonal papules and porcelain-white plaques with atrophic fragile skin, fissures, telangiectasias, purpura, erythema, erosions, and different degrees of sclerosis are present in the anogenital area (Figs. 65-1A–65-1F); often the classical figure-8 pattern of the vulva and anus may be observed (see Fig. 65-1E). Blisters (occasionally hemorrhagic) may develop when the lichenoid infiltrate separates epidermis from the sclerotic dermis. The size of LS lesions may vary from a few millimeters to large portions of the trunk. Anogenital LS frequently causes intractable itching and soreness, dyspareunia, dysuria, discomfort with defecation, or genital bleeding and, with time, may lead to destructive scarring (see Fig. 65-1F). Gradual obliteration or synechiae of the labia minora and clitoris, as well as stenosis of the introitus, may also result (see Chapter 78). Male genital LS is usually confined to the glans penis, prepuce, or foreskin remnants (see Fig. 65-1A–65-1C). Penile shaft involvement is less common, whereas scrotal involvement is rare. Many male genital LS cases are simply diagnosed as phimosis. In severe cases, erections may become painful (see Chapter 77). Extragenital manifestations typically affect the thigh, the neck, trunk and lips; lesions are usually asymptomatic (Fig. 65-2). A recent clinical histopathological study has revealed 27 adult cases with lip involvement.16 Clinical presentation consisted of asymptomatic vitiligo-like lesions in 70% with a variable degree of dermal sclerosis confined to the papillary layer. This was in contrast to genital LS lesions that showed both papillary and reticular dermal sclerosis in the majority of cases. Therefore, the vitiligo-like LS needs to be added to this spectrum of oral lichenoid lesions.

Figure 65-1

A. Early sclerosis and significant hemorrhage on the glans in early lichen sclerosus. B. Sclerosis of the frenulum and increased vulnerability with bleeding upon sexual intercourse. C. Significant sclerosis of the glans and conglutination with the preputium in advanced lichen sclerosus. Note narrowing of the urethral orifice and hemorrhage. D. In addition to the well-demarcated white vulvar plaque that is classic for lichen sclerosus, the waxy and crinkled texture, purpura (small arrows), and erosions (large arrow) are diagnostic. E. Sclerotic vulva with disappearance of the smaller labia and shrinkage of the introitus. Significant erythema and erosions are seen on the vulva and the anus in a figure-8 configuration. The patient complained of severe pruritus and dyspareunia. F. Erosive, sclerotic vulva in an 8-year-old girl.

Except for the association with autoimmune thyroid disease, alopecia areata, pernicious anemia, morphea, and vitiligo, which should be ruled out, no additional related findings have been reported. In particular, genital infections by herpes simplex virus or Candida do not seem to be increased in LS patients.

Laboratory Tests

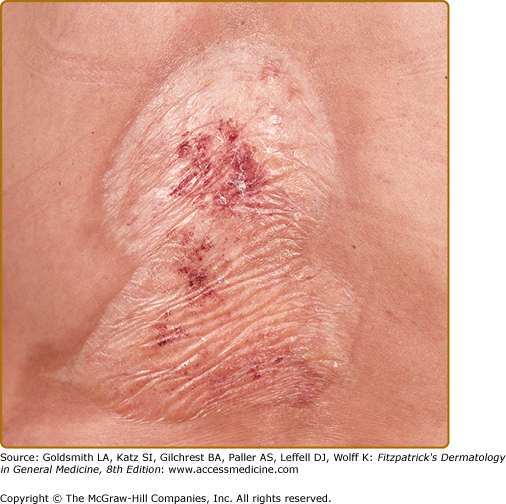

Classical LS shows an atrophic epidermis and a lichenoid infiltrate at the dermal–epidermal junction.17 Papillary edema is usually seen in early LS, but is gradually replaced by fibrosis with homogenization of acid mucopolysaccharides as the lesion matures (Fig. 65-3). The lymphocytic infiltrate in LS contains abundant T cells, B cells, and antigen-presenting dendritic cells that are major histocompatibility complex class II+, CD8+, and CD57+.18,19 A monoclonal T-cell receptor γ-chain rearrangement has alluded to the existence of an LS antigen, potentially the ECM-1 protein, which is also recognized by the recently described autoantibodies.8,20 Epidermal hyperplasia and/or dysplasia associated with LS on vulvar specimens are associated with an increased risk of malignant transformation, especially in conjunction with infection by high-risk papillomaviruses.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

A skin punch biopsy of a mature lesion will confirm the diagnosis if the diagnosis is not obvious by clinical examination. ECM-1 autoantibodies may be detected by specialized laboratories; a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) has recently become available.21 Despite the described association with autoimmune diseases, an autoimmune workup (e.g., antinuclear antibody, parietal cell antibody, vitamin B12 levels, thyroid function tests) is not generally recommended due to their relatively low occurrence.22 For the same reason, Borrelia antibody titers should not be analyzed, as they are not associated with LS.23 To exclude squamous cell carcinoma, repetitive biopsies may be indicated.

The differential diagnosis of LS and localized scleroderma (morphea) may be difficult (Box 65-1; see Fig. 65-2). Clinically, morphea may be confused with extragenital LS. Morphea represents a circumscribed connective tissue disease with a number of different presentations. Typical early plaque-type lesions show a lilac ring with progressive central induration and whitening and peripheral hyperpigmentation (see Chapter 64). Histologically, early morphea presents as a dense lymphocytic, superficial, and deep perivascular infiltrate with degeneration of collagen fibers. In later stages, inflammation is replaced by dermal fibrosis much like the changes seen in LS. Patients have been described with lesions typical of both plaque-type morphea and the chalky white, atrophic plaques of LS, suggesting that morphea and LS may share a common pathomechanism.24 Antinuclear antibodies may be positive in either morphea or LS.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree