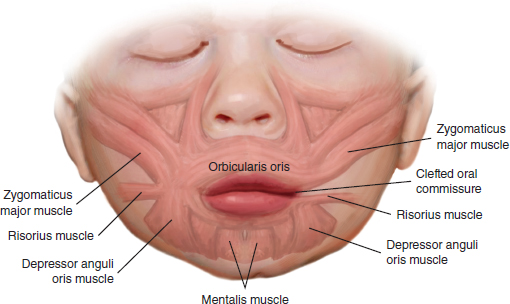

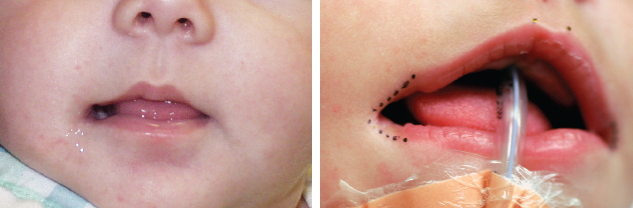

53 ○ Transverse clefts account for less than 1% of all facial clefts. ○ Transverse clefts are associated with anomalies of the first and second branchial arches. ○ Transverse clefts present with macrostomia and lateral displacement of the oral commissure. ○ Surgical repair is usually performed at 3 months of age. ○ Surgical repair involves reorientation of the muscle bands to overlap at a point that mirrors the contralateral, normal side. Unlike the more familiar clefts of the lip and palate, transverse facial clefts are relatively rare anomalies. Such lateral clefts that involve the oral commissure constitute less than 1% of all facial clefts. They are commonly associated with anomalies that affect structures derived from the first and second branchial arches and may affect either one or both sides of the face (Fig. 53-1). The embryologic process that results in a transverse cleft is postulated to be a failure in obliteration of the normal grooves that exist between the fetal maxillary and mandibular prominences, a process that normally occurs in the fourth and fifth weeks of gestation.1,2 Transverse facial clefts are most recognizable by the larger-than-normal width of the mouth and the deficiency of soft tissue (and possibly bone) just lateral to the oral commissure. The normal oral commissure is not a simple union of upper and lower lip elements but rather a continuous, circumoral band of vermilion mucosa.3,4 Beneath the mucosa are interdigitating fibers of the orbicularis oris muscle that parallel the upper and lower lip elements. Accurate reconstruction of the oral commissure needs to re-create this anatomic configuration, which is important for both feeding and speaking5 (Fig. 53-2). In the presence of a transverse cleft, the normal anatomy is lost as the bands of muscle continue to remain parallel to the margins of the cleft but fail to interdigitate with one another as they course laterally. The upper lip muscle often interdigitates with the superiorly based zygomaticus muscle, and the lower lip muscle interdigitates with the inferiorly based risorius muscle (Fig. 53-3). Fig. 53-1 Right-sided transverse facial cleft of macrostomia. Fig. 53-2 Left-sided lateral facial cleft. A, Unrepaired. B, The repaired cleft is seen postoperatively in repose, and C, in animation. Numerous techniques have been proposed in the literature to achieve an acceptable result. Borrowing from the principles of Estlander for lip reconstruction, May6 advocated rotation of a full-thickness, vermilion-lined flap, including muscle, from the lower lip to the upper as a means of reconstructing the commissure. Longacre et al7 proposed a lateral Z-plasty of the cheek incision to more closely reconstruct the normal creases of skin. Torkut8 applied the double-reversing Z-plasty, similar to that used for cleft palate repair, to address transverse facial clefts. One lip margin contributed an external flap of skin and an internal composite flap of orbicularis muscle and oral mucosa. The other lip contributed an external flap of skin and muscle and an internal flap solely of mucosa. More recently, Fukada and Takeda9 described advancing the entire corner of the mouth as a composite flap from its existing location to a more anatomic one. The intervening medial segments of vermilion were excised together with a triangle of oral mucosa, and the resulting ends were reapproximated with the commissure in a more medial position. Eguchi et al10 designed a vermilion square flap method that straddled the mucocutaneous border and crossed the commissure to place the suture line away from the corner of the mouth. They specifically raised their vermillion flap off the lower lip because the resultant scar would rest on the upper lip. They believed that lower lip scars become more conspicuous over time as a result of continuous tension with opening the mouth, which is not similarly seen in the upper lip. A W-plasty was used to reapproximate the lateral skin. The principles of repair of a transverse facial cleft include accurate placement of the commissure to restore symmetry to the lower third of the face, re-creation of the orbicularis oris muscle as a sphincter around the mouth, minimizing external scarring, and prevention of secondary contracture that displaces a correctly positioned commissure. The more established reconstructive techniques use flaps of skin, mucosa, or both that place the suture line over the bulk of either the upper or lower lip to prevent a scar at the corner of the mouth. Scars in these areas tend to heal better from a cosmetic standpoint as well as a functional one. A major goal of reconstruction is to prevent a tight, noticeable scar extending across the cheek from the corner of the mouth. Transverse facial clefts are recognizable at the time of delivery by the larger-than-normal width of the mouth. The distance between the oral commissure and the tragus of the ear on the affected side of the face is reduced. At rest, the commissure does not close, and with pursing and speaking, the lips fail to completely close. Soft tissue and bone in the region lateral to the oral commissure also may be deficient. Because transverse facial clefts are commonly associated with anomalies that affect the structures derived from the first and second branchial arches, these should be carefully examined on both sides of the face. The ipsilateral helical framework and mandible, as well as the muscles of facial expression and glands, may be affected. As noted, macrostomia may be associated with numerous syndromes that affect other organ systems, including the heart, which are important to identify early. Noonan syndrome, for instance, is an autosomal dominant anomaly that includes congenital heart defects (pulmonary valve stenosis, atrial septal defect, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy), short stature, learning problems, pectus excavatum, impaired blood clotting, and a characteristic configuration of facial features including a webbed neck and a flat nose bridge. Patients with Treacher Collins syndrome have downward slanting eyes, micrognathia, conductive hearing loss, zygoma hypoplasia, and microtia. Williams syndrome is a neurodevelopmental disorder caused by a deletion of approximately 26 genes from the long arm of a chromosome. Characteristic features include a cheerful “cocktail party” demeanor with strangers, an elflike facial appearance, developmental delay, cardiovascular anomalies (supravalvular aortic stenosis), and transient hypercalcemia. Similar to more conventional cleft lip repairs, surgery is usually repaired in the first year of life. Earlier closure may improve feeding but should have no appreciable effect on speech and language development. As stated previously, associated congenital anomalies should be screened for and addressed before surgery. The ability to undergo reconstruction of the lip is of paramount importance. Children with transverse facial clefts should be able to feed with minimal assistance, including smaller and more frequent feedings in a more upright position, often with cleft nipples with a larger opening or reservoir. However, they should be healthy enough, as noted by weight gain and the absence of concomitant problems, to tolerate 2 to 3 hours of general anesthesia with minimal fluid shifts and blood loss. The proper position of the new commissure may be determined in several ways. First, the face should be inspected in static, forward gaze. The normal commissure should fall along a straight line dropped from the medial limbus of the iris. The cleft side should be carefully inspected for a distinct change in the color and contour of the vermilion edge. This should also correspond to the normal commissure position. Alternatively, the distance between the normal side commissure to the Cupid’s bow high point can be accurately measured, and this distance transferred to the aberrant side and the new position marked.

Lateral Transverse Facial Clefts

Peter J. Taub, Joseph E. Losee

KEY POINTS

BACKGROUND AND HISTORY

RECONSTRUCTIVE PRINCIPLES

PATIENT SELECTION AND EVALUATION

MANAGEMENT ALGORITHM

Timing of Repair

PREOPERATIVE AND POSTOPERATIVE FACTORS

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE

Preoperative Marking

Plastic Surgery Key

Fastest Plastic Surgery & Dermatology Insight Engine