CHAPTER 6 Involutional Periorbital Changes

Dermatochalasis and Brow Ptosis

Introduction

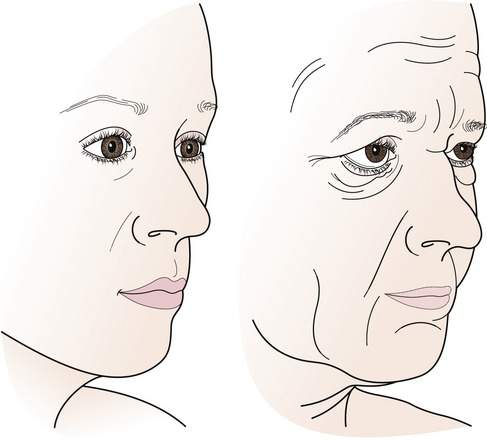

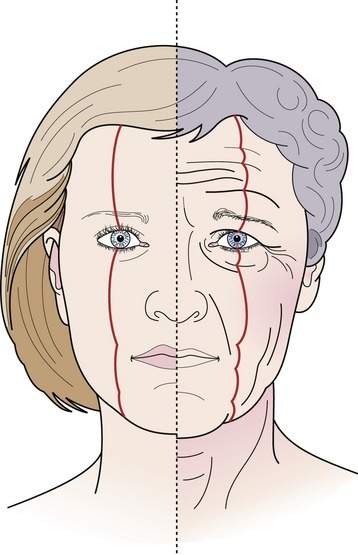

A detailed examination will identify specific anatomic abnormalities that need to be addressed during surgery. These abnormalities include (1) low brow position; (2) abnormal brow contour, especially temporal droop; (3) redundant eyelid skin and muscle; (4) prolapsing orbital fat; (5) upper eyelid ptosis; (6) lower lid retraction; (7) lower eyelid laxity; and (8) abnormal orbital bony architecture. Midface, lower face, and neck changes should be identified as well. Once these individual factors are identified, their specific relationship to one another needs to be determined (Figure 6-1).

We will cover procedures that make your patient “see better” first. These include functional browplasty and upper blepharoplasty. We will discuss the principles of upper blepharoplasty from a reconstructive point of view. Although this procedure is essentially the same for reconstructive and aesthetic purposes, there may be individual differences, depending upon the patient’s goals. We will point out some of these nuances. Procedures that make your patient “look better” will be covered in the next chapter. As usual, in every operation, you should make an attempt to avoid complications of surgery including asymmetry, dry eye, lower lid retraction, and postoperative hemorrhage.

Anatomic considerations

The eyebrow

Parts of the eyebrow

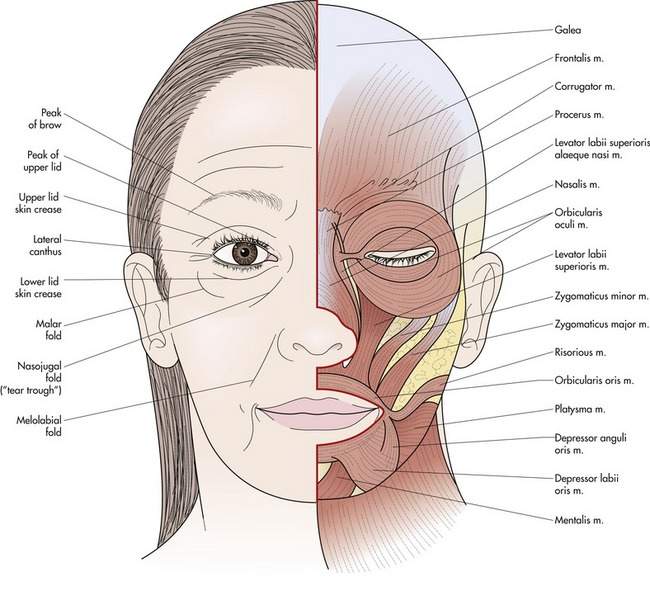

The eyebrow has three parts, the head, body, and tail. The direction of the brow hairs varies from upward in the head of the brow to horizontal and slightly downward in the tail of the brow. The eyebrow is part of the forehead with similar thick skin and abundant sebaceous glands. The thick skin of the brow blends in with the thinner upper eyelid skin of the skin fold (Figure 6-2). You will be able to see and feel this transition.

Male and female eyebrows

The male and female brows differ considerably in position and shape. The male brow is lower than the female brow, resting at the edge of the superior orbital rim. The female brow is higher, especially in its temporal aspect, and sits above the orbital rim. The female brow tends to be somewhat thinner and is frequently manicured to emphasize a temporal arch with the highest point generally occurring at the junction of the body and tail of the brow (see Figure 2-4).

Movement of the eyebrow

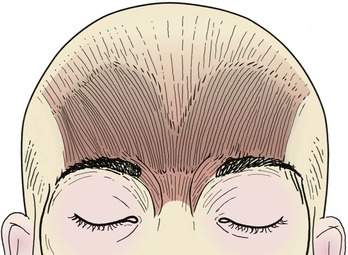

The normal eyebrow moves independently of the upper lid. Extreme elevation of the eyebrow, as seen with severe upper lid ptosis, causes only slight elevation of the eyelid. The elevator of the eyebrow is the frontalis muscle (Figure 6-3), which extends from the brow over the forehead to merge with the broad fibrous tissue of the galea aponeurotica. Elevation of the frontalis muscle causes the horizontal furrows frequently seen in the forehead. Innervation of the frontalis, like that of other muscles of facial expression, comes from a branch of the facial nerve, the frontal branch. This single nerve provides innervation to the brow on the same side. The approximate position of the frontal nerve can be estimated by drawing a line from the tragus of the ear to 1 cm above the tail of the brow (see Figure 2-27).

Temporal brow droop

You will notice that the width of the frontalis muscle stops short of the tail of the brow. Consequently, elevation of the temporal brow often becomes deficient with aging, causing a temporal brow droop (Figure 6-4). As the brow droops, the upper lid skin fold is pushed down, accentuating the upper lid fold, often misinterpreted as redundant skin. Look for this problem in your older patients. It is so common that you may be ignoring it.

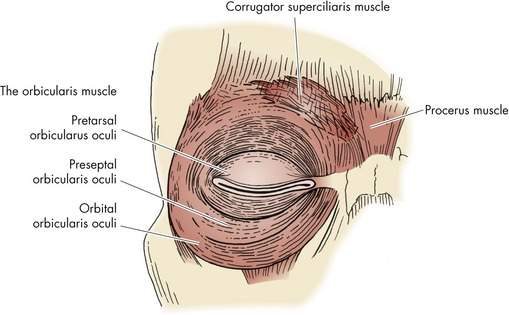

The glabellar folds

The protractors, or depressors, of the eyebrow are the orbital orbicularis, the procerus, and the corrugator muscles (Figure 6-5). Contraction of the orbicularis muscle closes the eye and pulls the eyebrow down. The vertical fibers of the procerus muscle at the head of the brow are responsible for the horizontal furrows in the glabella. The C-shaped corrugator muscle pulls the head of the eyebrow medially and downward, causing the vertical glabellar wrinkles. Wrinkles in the area of the glabella are a common cosmetic concern among women. In many cases, these wrinkles may give an anguished or angry look to the face (see Figure 2-16).

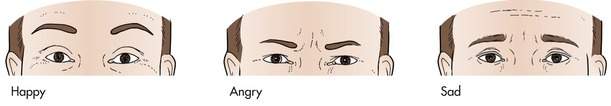

The muscles of the eyebrows are among the most important muscles of facial expression. They are strong indicators of mood and feeling. This is best demonstrated by a simple diagram of the familiar happy face (Figure 6-6). A downward slope to the medial aspect of the eyebrows with associated glabellar wrinkles tends to convey anger. A drooping of the temporal brow suggests melancholy. Arched normally contoured eyebrows indicate happiness. Elevation of the arched brow with associated forehead furrows tends to indicate surprise. You may have seen this diagram in other texts. It is a very useful concept.

There are many operations that raise the eyebrows. Compare the extremes—a temporal direct brow lift and a coronal forehead lift—the former lifting the lateral part of the eyebrow and the latter lifting the eyebrows and entire forehead. You will see that the temporal lift uses a short incision placed at the lateral third of the brow hairs. It corrects the temporal sag and helps to clear the field of vision. It does nothing for the medial brow or the glabella. The coronal forehead lift is performed through an incision across the top of the head from “ear to ear.” The entire forehead and eyebrows are raised. In addition, the glabellar folds, forehead furrows, and the redundancy of the eyelid skin under the medial brow are all improved. The overall result of the coronal lift is more aesthetically pleasing. Most forehead lifts are done for the “cosmetic” improvement and are “self-pay” procedures. You can guess that the recovery time and operating time for the two procedures are much different. Despite a long scar in the hairline for a coronal lift, it is less visible than the shorter scar over the eyebrow. However, the top of the head is left with some degree of numbness. You will learn which procedure is the best choice for your patient. I have somewhat arbitrarily divided these procedures as “functional eyebrow lifting procedures” and “cosmetic forehead lifting procedures” and will discuss them in separate chapters.

The upper eyelid

The skin fold, superior sulcus, and skin crease

The upper eyelid consists of three parts:

The skin and muscle between the eyebrow and the lid crease form the upper lid skin fold (see Figure 6-2). To have normal movement of the eyelid, there needs to be some redundancy in the eyelid tissues. This movement is provided by the skin fold. The skin fold is bounded by the eyebrow above and the skin crease below.

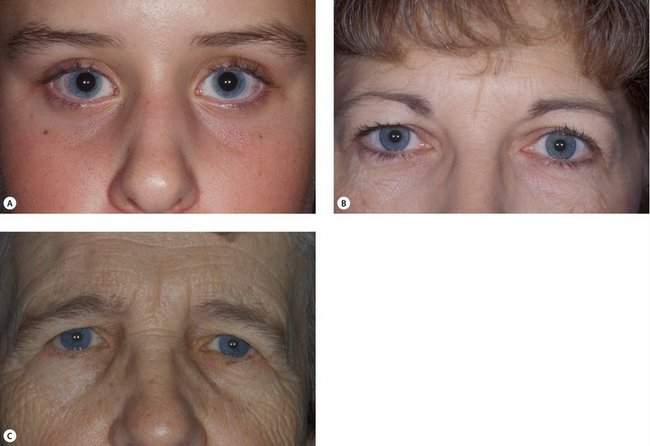

A complex interaction of anatomic factors affects the fullness of the skin fold and the depth of the sulcus. Younger patients tend to have a minimal skin fold. The brow is well supported, and there is little prolapse of orbital fat (key factors for a young skin fold). The levator muscle pulls the pretarsal portion of the lid into the orbit. In children, the skin fold appears to be more a part of the eyebrow than of the eyelid. As the bony forehead develops in children and young adults, the fold lifts and remains tight against the brow, and a superior sulcus develops. With age, the brow descends and orbital fat prolapses, tending to fill in the sulcus and to increase the fullness of the skin fold of the older adult (Figure 6-7). You may want to reread this. It is an important concept if you want to attain any level of sophistication in performing blepharoplasty.

The upper eyelid skin and the orbicularis muscle

The muscle underlying the eyelid skin is the orbicularis muscle. You are familiar with the three portions of the orbicularis muscle: the orbital, the preseptal, and the pretarsal portions. The orbital orbicularis muscle interdigitates with the procerus, corrugator, and frontalis muscles at the glabellar region (see Figure 6-5).

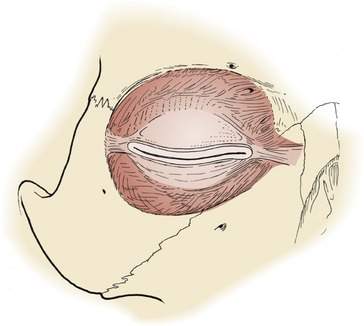

The orbital septum

The orbital septum lies directly beneath the orbicularis muscle. It is a fibrous layer arising from the periosteum of the orbital rims. The septum functions as an anatomic boundary of the lids, separating the eyelids from the orbit (Figure 6-8). Although this fibrous tissue is quite tough, it also allows for vertical movement of the eyelid. With aging, weakening of the orbital septum allows fat to prolapse in the eyelid. When no fat prolapse is present, the orbital septum is not opened during upper lid blepharoplasty. When orbital fat prolapse is present, the orbital septum may be opened and fat is excised or repositioned. Fat prolapse is the main indication for blepharoplasty in the lower eyelid. Because the septum is not elastic, it should never be sewn closed as this may contribute to lagophthalmos. With aging, the smooth transition from the lower eyelid to the cheek is lost. Fat prolapse and associated cheek descent transforms the single convex surface of the eyelid and cheek to the so-called “double convexity” that is part of the aging midface. We will learn about this more later.

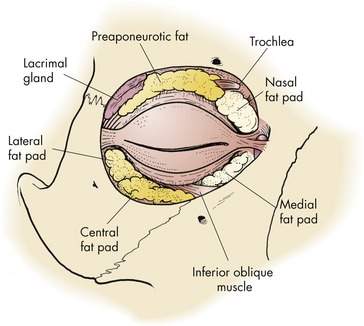

The preaponeurotic fat

The upper eyelid preaponeurotic fat is divided into two compartments containing the preaponeurotic or central fat and the nasal or medial fat. The lacrimal gland fills in the temporal aspect of the preaponeurotic space in the upper lid (Figure 6-9). The lacrimal gland is distinguished from the fat by its whitish color and lobulated surface. A branch of the palpebral artery runs posterior to the nasal fat pad. You should be careful not to inadvertently cut this artery because brisk bleeding will occur. The nasal fat pad is whiter in color than the central fat pad.

The amount and position of the fat prolapse varies from patient to patient. No fat prolapse is seen in many patients. These patients may have dermatochalasis only and do well with only skin and muscle being removed during upper lid blepharoplasty. Nasal fat prolapse is especially common, but patients may have fat prolapse in any combination of locations (Figure 6-10).

The lower eyelid

The lower eyelid position and contour

The normal lower eyelid rests at the limbus. The lateral canthus is slightly higher than the medial canthus in most patients. The lowest point of the lower lid is inferior to the lateral limbus (see Figure 6-2).

The position of the lower eyelid is dependent on several factors including:

• The inferior rim bony prominence

• The horizontal tension of the lower eyelid

• The length of the anterior or posterior lamellae of the eyelid

We saw in our discussion of ectropion (see Chapter 3) that patients with less prominent inferior orbital rims (maxillary hypoplasia or “hemiproptosis”) are more susceptible to lid retraction and ectropion. Another way to evaluate this is to view the patient from the side and draw a line from the cornea to the inferior orbital rim. If the line slopes toward the cheek, the patient is said to have a negative vector (the same as what we have termed hemiproptosis). Shortening of the skin, muscle, or conjunctiva from sun, disease, trauma, or surgery can cause lower lid retraction. You will learn to respect the forces that hold the lower eyelid in position. It does not take much to alter the balance of these forces to cause lower lid retraction, the most common complication of lower lid blepharoplasty.

The lower eyelid skin and muscle

Briefly, let’s consider the general aging changes of the face:

The parts of the orbicularis muscle in the lower eyelid have the same names as those in the upper eyelid. The orbital portion extends on the cheek. In young patients, there is a smooth transition from the eyelid margin to the cheek. With aging, the lower eyelid preaponeurotic fat prolapses forward, and a convexity to the surface of the lower eyelid is created. The descent of the cheek, once cushioning the inferior orbital rim, causes the orbital rim to be palpable and appear depressed. The smooth transition from the eyelid to the cheek is lost and a “double convexity” (Figure 6-11) is created in profile. Lifting the cheek (midface) in combination with lower eyelid blepharoplasty can restore the youthful smooth profile to the eyelid and cheek. As you become more aware of facial aesthetics, you will notice how the aging process affects all your patients. We will talk more about the anatomy that applies to aesthetic procedures in the next chapter.

Figure 6-11 The “double convexity” of the lower eyelid. Descent and deflation aging changes transform the youthful smooth facial contours into a series of “sags and bags.” As the cheek descends and the eyelid fat prolapses forward, the normal smooth contour of the lower eyelid is lost and the “double convexity” forms (based on McCord, Ch. 2, Fig. 2.14).

The lower eyelid fat

The lower lid fat includes nasal, central, and temporal fat pads (see Figure 6-9). The nasal fat pads in both upper and lower lids are somewhat whiter than the other fat pads.

Checkpoint

At this point, you should understand the changes that occur in the aging of the face:

History

General medical and ocular history

How about the feared “dry eye.” It is best to ask about a burning or foreign body sensation in the eyes and the use of artificial tears. A sensitivity to moving air, from ceiling fans, air vents, or windshield defrosters, may indicate a “dry eye.” Asking if the patient has been told if he or she has a dry eye is not helpful. Many patients have been given this diagnosis incorrectly, and it will not likely complicate your blepharoplasty result. A patient who benefits from using artificial tears once a day does not really have a “dry eye.” We will talk about this topic more in Chapter 10.

Physical examination

Questions to be answered

In the physical examination, you will be answering these questions:

• What is the normal anatomy and function?

• What is the structural abnormality? How does the patient’s anatomy differ from normal? How are functions altered?

• What is the patient’s complaint? What are the patient’s goals? (functional or cosmetic) What is the patient’s desired outcome? (specific postoperative appearance) What is the potential for meeting these goals?

• What are the options for attaining the patient’s goals? What is the best surgical plan?

• Are there contraindications for getting the desired result?