Introduction: Plastic surgery contributions to hand surgery

Origins of hand surgery

Henry C Marble, in Flynn’s classic textbook, Hand Surgery, found the earliest references to surgery of the hand by Hippocrates (460–377 bc) in ancient Greece.1 In his writings, Hippocrates described methods to reduce wrist fractures and also highlighted the importance of well-fitting, clean dressings to the hand. A later Greek physician, Heliodorus, described his technique for amputation of a finger with specific reference to dissecting adequate skin flaps with which to cover the remaining bone. While Galen (131–201 ad) confused tendons with nerves and cautioned against suturing tendons for fear of “nervous spasms,”2 Avicenna (981–1038 ad),3 an Arabian physician, wrote detailed descriptions of tendon repair in medieval times. Other references to hand surgery have been found in history, but comprehensive care of the hand was not truly developed until the 20th century.

An understanding of human anatomy has been critical to both plastic surgery and hand surgery, and therefore, the history of anatomy has paralleled the development of these two surgical disciplines. J William Littler reviewed the influence of famed anatomists on hand surgery.4 Perhaps these anatomists were drawn to the hand as the most intricate of body parts – the ultimate challenge to their craft. In the Renaissance period, Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) used his artistic genius to create extraordinarily accurate representations of the hand. His knowledge of anatomy was acquired from over 100 human dissections and ultimately resulted in a collection of 779 anatomical drawings.5

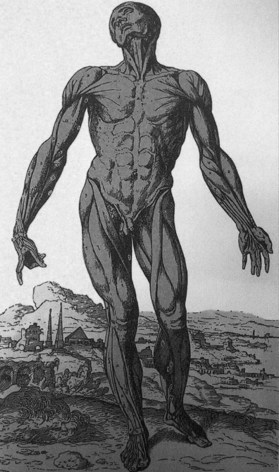

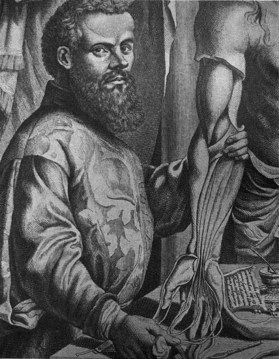

Andreas Vesalius (1514–64) (Figs 1 and 2) published his monumental work De Corporis Humani Fabrica in 1543 with many engravings dedicated to the hand.6 Like da Vinci, Vesalius relied on his own dissections of cadavers rather than accepting the dogma found in previous medical texts. His observations refuted the inaccuracies found in the earlier writings of Galen and his disciples. Modern-day hand surgeons J William Littler and Robert A Chase have both credited Sir Charles Bell (1774–1842) as the foremost anatomist of the hand.7 His Fourth Bridgewater Treatise – The Hand: Its Mechanism and Vital Endowments as Evincing Design (1834) remains a classic essay on the anatomic and functional aspects of the hand.8

Fig. 1 Andreas Vesalius, master anatomist, at the age of 28.

(Reproduced from Haeger K. The Illustrated History of Surgery. Gothenburg, Sweden: AB Nordbok, 1988.)

In addition to anatomy, two more recent achievements allowed hand surgery to develop into a unique specialty in the modern era. On October 16, 1846 at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Dr. William Morton delivered sulfuric ether fumes to a patient undergoing excision of a neck mass by Dr. John Collins Warren.9 For the first time, adequate anesthesia was performed, thus allowing the possibility of more complex reconstructive procedures in both plastic surgery and hand surgery.

The second major achievement was an understanding of microbiology with resulting advances in sterile technique and antibiotics.10 In the 1860s, Louis Pasteur’s work with fermentation introduced the field of bacteriology. Semmelweis, in Vienna, and Lister, in England, developed antiseptic surgery with the early use of carbolic acid as a disinfectant. In the 20th century, several Nobel Prizes marked the importance of the development of antibiotics. Paul Erlich, a German bacteriologist, developed the principle of “antimicrobial chemotherapy” and received the Nobel Prize in 1908. Another German, Gerhard Domagk, received the Nobel Prize in 1939 for discovering the antibacterial effects of sulfa drugs. Finally, Alexander Fleming shared the Nobel Prize in 1945 for discovering the ability of a mold, Penicillium notatum to halt the growth of staphylococcus bacteria. With penicillin and later antibiotics, plastic surgeons and hand surgeons had an armamentarium of agents to control infections.

Principles of plastic surgery and their application to hand surgery

The physician should take the leaf of a tree the same size as the nose and apply it to the cheek in such a way that a stem is still adherent. Then he stitches the cheek with needle and thread, scarifies the stump of the nose and quickly but carefully places the flap in the nose. After the transplanted piece has grown, the stem is cut off. In like manner the flap might be turned up from the upper or lower arm and attached to the nose – with the arm over the head.11

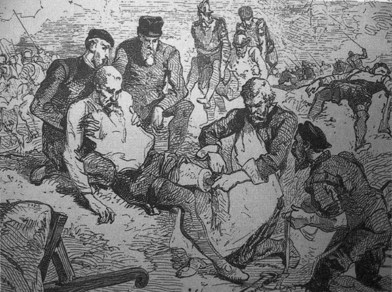

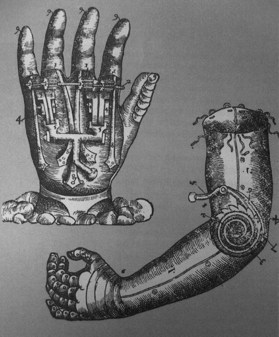

Another famed surgeon, Ambrose Paré (1510–90), offered principles that allowed for optimal care of battlefield wounds, including the upper extremity: “to enlarge the wound for drainage; to remove bone splinters and foreign bodies from wounds; to control hemorrhage with ligatures; not to encourage suppuration; and to amputate through sound tissues.”12 Paré’s use of ligatures during amputation controlled hemorrhage and saved countless lives on the battlefield (Figs 3 and 4). His principles of wound care would later be applied directly to the enormous number of battlefield casualties of World War II. In addition, Paré popularized the anatomic drawings of Vesalius amongst surgeons, and even designed elaborate prostheses for upper extremity amputees, victims of the French wars of the 1500s. Paré was perhaps the quintessential upper extremity trauma surgeon.

Fig. 3 Ambrose Paré applying a ligature during battlefield amputation.

(Reproduced from Haeger K. The Illustrated History of Surgery. Gothenburg, Sweden: AB Nordbok, 1988.)

Fig. 4 Examples of Paré’s designs for prostheses.

(Reproduced from Haeger K. The Illustrated History of Surgery. Gothenburg, Sweden: AB Nordbok, 1988.)

Gaspare Tagliacozzi (1545–99) did not invent the Italian method of nasal reconstruction, which has been generally attributed to Branca. However, Tagliacozzi, a professor of medicine and anatomy in Bologna, did popularize this technique of attaching a medial upper arm skin flap to the nasal defect. In addition, specialized leather band contraptions were devised to immobilize the patient during the period of flap revascularization (Fig. 5). His detailed textbook, De Chirugia Curtorum per Insitionem, was published in 1597 and allowed later generations of surgeons to learn techniques for the transfer of distant pedicled flaps.13

Fig. 5 Tagliacozzi’s immobilization device after arm-to-nose pedicled transfer.

(Reproduced from Haeger K. The Illustrated History of Surgery. Gothenburg, Sweden: AB Nordbok, 1988.)

As plastic surgeons became more adept at tissue transfer, these innovations were applied to reconstruction of the hand. Carl Nicoladoni (1849–1903) pioneered work on reconstruction of the thumb. Nicoladoni reported on a case of total skin avulsion of the thumb that he treated by a skin flap from the patient’s left pectoral region – similar to the thoracoepigastric or random pattern chest flaps still used today.14 In 1903, his paper, “Further experience with thumb reconstruction,” described the pedicled toe transfer to the thumb that continues to bear his name. Microsurgeons today have obviated the need for the uncomfortable positioning of this transfer; nevertheless, Nicoladoni deserves credit for the ingenuity behind the toe-to-hand transfer. Plastic surgeon George H Monks (1853–1933) transferred a composite skin island flap from the forehead on the superficial temporal arteriovenous pedicle to a lower-eyelid defect.15 The use of island flaps would later be applied to the hand with the neurovascular island flaps of Littler, and, more recently, with the dorsal metacarpal artery flaps. Even Sir Harold Gillies (1882–1960) who, with Millard, codified the principles of plastic surgery and was one of history’s most influential plastic surgeons, turned from the head and neck to the hand and devised a method to lengthen the stump of a thumb, the Gillies “cocked-hat” flap.16

Vilray P Blair (1871–1955) was one of the founding fathers of American plastic surgery.17 In addition to a large body of work in cleft lip repair and maxillofacial surgery, Blair made two significant contributions to plastic surgery that translated directly to hand surgery. Blair helped redefine the delay phenomenon of Tagliacozzi in a 1921 article, “The delayed transfer of long pedicled flaps in plastic surgery.” Blair and his disciple, James Barrett Brown (1899–1971), described a new technique of harvesting skin for skin grafting in a paper published in Surgery, Gynecology, and Obstetrics entitled “The use and uses of large split skin grafts of intermediate thickness.”18 This simple and reproducible method of harvesting split-thickness skin improved on the previous techniques of Thiersch and would have a tremendous impact on the reconstruction of hand burns and other wounds in World War II.

Origins of modern hand surgery

With this historical background in wound management, flap transfer, and skin grafting, plastic surgeons were poised to contribute to the founding of modern hand surgery. World War II was the crucible in which hand surgery became a separate specialty. Prior to the outbreak of this war, two surgeons were instrumental in hand surgery’s early development. In 1939, Allen B. Kanavel published his Infections of the Hand,19 and for the first time, a comprehensive approach to the myriad of hand infections and treatments was described. Even at that early time, Kanavel stressed the importance of hospitalization for hand infections, intravenous hydration, and placing the hand at rest.

Sterling Bunnell (1882–1957) has been widely regarded as the father of hand surgery. The first edition of Bunnell’s comprehensive textbook, Surgery of the Hand,20 was published in 1944, and remained the classic reference for many years. He was a general surgeon but believed in the importance of plastic surgery principles, and as the consummate hand surgeon, was able to apply plastic, orthopedic, and vascular principles equally to hand surgery. Marble recounted Bunnell’s mastery:

He insisted on all of the teachings of the past masters, stressing particularly the gentle handling of the tissues. He called this atraumatic surgery. He exercised his skill also in plastic, bone, tendon, nerve, blood vessel, and muscle surgery to reconstruct crippled hands. He showed that tendons could be grafted to substitute for lost ones, and could be transferred to give function to useless digits or joints. He taught that nerves could be grafted and that whole fingers could be moved about for better function. Thus he opened the door for the complete reconstruction of the injured hand.21

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree