Chapter 1

Introduction

OVERVIEW

- The clinical features of skin lesions are related to the underlying pathological processes.

- Skin conditions broadly fall into three clinical groups: (i) those with a well-defined appearance and distribution; (ii) those with a characteristic pattern but with a variety of underlying clinical conditions; (iii) those with a variable presentation and no constant association with underlying conditions.

- Skin lesions may be the presenting feature of serious systemic disease, and a significant proportion of skin conditions threaten the health, well-being and even the life of the patient.

- Clinical descriptive terms such as macule, papule, nodule, plaque, induration, atrophy, bulla and erythema relate to what is observed at the skin surface and reflect the pathological processes underlying the affected skin.

- The significance of morphology and distribution of skin lesions in different clinical conditions are discussed.

Introduction

The aim of this book is to provide an insight for the non-dermatologist into the pathological processes, diagnosis and management of skin conditions. Dermatology is a broad specialty with over 2000 different skin diseases, the most common of which are introduced here. Pattern recognition is key to successful history-taking and examination of the skin by experts, usually without the need for complex investigations. However, for those with less dermatological experience, working from first principles can go a long way in determining the diagnosis and management of patients with less severe skin disease. Although dermatology is a clinically orientated subject, an understanding of the cellular changes underlying the skin disease can give helpful insights into the pathological processes. This understanding aids the interpretation of clinical signs and overall management of cutaneous disease. Skin biopsies can be a useful adjuvant to reaching a diagnosis; however, clinicopathological correlation is essential in order that interpretation of the clinical and pathological patterns is put into the context of the patient.

Interpretation of clinical signs on the skin in the context of underlying pathological processes is a theme running through the chapters. This helps the reader develop a deeper understanding of the subject and should form some guiding principles that can be used as tools to help assess almost any skin eruption.

Clinically, cutaneous disorders fall into three main groups.

- Those that generally present with a characteristic distribution and morphology that leads to a specific diagnosis—such as chronic plaque psoriasis, basal cell carcinoma and atopic dermatitis (Figure 1.1).

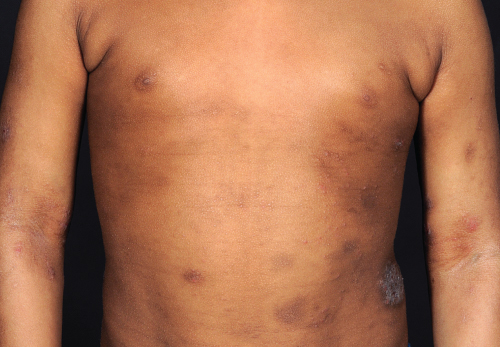

- A characteristic pattern of skin lesions with variable underlying causes—such as erythema nodosum (Figure 1.2) and erythema multiforme.

- Skin rashes that can be variable in their presentation and/or underlying causes—such as lichen planus and urticaria.

Figure 1.1 Atopic dermatitis.

Figure 1.2 Erythema nodosum in pregnancy.

A holistic approach in dermatology is essential as cutaneous eruptions may be the first indicator of an underlying internal disease. Patients may, for example, first present with a photosensitive rash on the face, but deeper probing may reveal symptoms of joint pains etc. leading to the diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Similarly, a patient with underlying coeliac disease may first present with blistering on the elbows (dermatitis herpetiformis). It is therefore important not only to take a thorough history (Box 1.1) of the skin complaint but in addition to ask about any other symptoms the patient may have, and examine the entire patient carefully.

Box 1.1 Dermatology history-taking

- Where—site of initial lesion(s) and subsequent distribution

- How long—continuous or intermittent?

- Trend—better or worse?

- Previous episodes—timing? Similar/dissimilar? Other skin conditions?

- Who else—Family members/work colleagues/school friends affected?

- Symptoms—Itching, burning, scaling, or blisters? Any medication or other illnesses?

- Treatment—prescription or over the counter? Frequency/time course/compliance?

The significance of skin disease

Seventy per cent of the people living in developing countries suffer skin disease at some point in their lives, but of these, 3 billion people in 127 countries do not have access to even basic skin services. In developed countries the prevalence of skin disease is also high; up to 15% of general practice consultations in the United Kingdom are concerned with skin complaints. Many patients never seek medical advice and self-treat using over-the-counter preparations.

The skin is the largest organ of the body; it provides an essential living biological barrier and is the aspect of ourselves that we present to the outside world. It is therefore not surprising that there is great interest in ‘skin care’ and ‘skin problems’, with an associated ever-expanding cosmetics industry. Impairment of the normal functions of the skin can lead to acute and chronic illness with considerable disability and sometimes the need for hospital treatment.

Malignant change can occur in any cell in the skin, resulting in a wide variety of different tumours, the majority of which are benign. Recognition of typical benign tumours saves the patient unnecessary investigations and the anxiety involved in waiting to see a specialist or waiting for biopsy results. Malignant skin cancers are usually only locally invasive, but distant metastases can occur. It is important therefore to recognize the early features of lesions such as melanoma (Figure 1.3) and squamous cell carcinoma before they disseminate.

Figure 1.3 Superficial spreading melanoma.

Underlying systemic disease can be heralded by changes on the skin surface, the significance of which can be easily missed by the unprepared mind. So, in addition to concentrating on the skin changes, the overall health and demeanour of the patient should be assessed. Close inspection of the whole skin, nails and mucous membranes should be the basis of routine skin examination. The general physical condition of the patient should also be determined as indicated.

The majority of skin diseases, however, do not signify any systemic disease and are often considered ‘harmless’ in medical terms. However, due to the very visual nature of skin disorders, they can cause a great deal of psychological distress, social isolation and occupational difficulties, which should not be underestimated. A validated measure of how much skin disease affects patients’ lives can be made using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). A holistic approach to the patient both physically and psychologically is therefore highly desirable.

Descriptive terms

All specialties have their own common terms, and familiarity with a few of those used in dermatology is a great help. The most important are defined below.

- Macule (Figure 1.4). Derived from the Latin for a stain, the term macule is used to describe changes in colour (Figure 1.5) without any elevation above the surface of the surrounding skin. There may be an increase in pigments such as melanin, giving a black or blue colour depending on the depth. Loss of melanin leads to a white macule. Vascular dilatation and inflammation produce erythema. A macule with a diameter greater than 2 cm is called a patch.

- Papules and nodules (Figure 1.6). A papule is a circumscribed, raised lesion, of epidermal or dermal origin, 0.5–1.0 cm in diameter (Figure 1.7). A nodule (Figure 1.8) is similar to a papule but greater than 1.0 cm in diameter. A vascular papule or nodule is known as a haemangioma.

- A plaque

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree