Chapter 61 Intentional burn injuries

![]() IN THIS CHAPTER

IN THIS CHAPTER ![]() Video Content Online • PowerPoint Presentation Online

Video Content Online • PowerPoint Presentation Online

![]() Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

Access the complete reference list online at http://www.expertconsult.com

Introduction

Deliberate injury by burning is often unrecognized. According to the US Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families,1 child abuse and neglect are defined as ‘any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker, which results in death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse or exploitation, or an act or failure to act which presents an imminent risk of serious harm.’ Within the USA alone, 1.5 million children are abused or neglected each year, with 4–39% of these occurrences being reported as intentional burn injuries and less than half ever being substantiated.2 It is imperative that all clinicians are aware of the importance of recognizing signs and symptoms of intentional injury presentations, as the opportunity for intervention is critical when taking into account that 50%3 of children experience recurrent abuse and 30% are ultimately fatally injured.4 Reporting suspicious injuries to child protective services is mandated by law for all clinicians working with children.5 Some treating facilities identify specific treatment team members (i.e. psychologist or social workers) to be responsible for all reporting. In these situations it may be necessary to follow the protocol of the hospital or treating facility first; however it is important to note that any physician, medical professional or mental health professional that encounters a suspicious injury must insure that the injury is reported to the appropriate authorities. At other times, the concern of reporting is more a result of ambiguity or vagueness in the information, which can cause hesitation to report the suspicious injury. In these incidents of doubt, the most salient point to remember is that the clinician is responsible to report suspicious injury not to prove or validate the abuse. It is always better to report the suspicion than to ignore it. Most state agencies also have hotlines that are available to call 24 h a day to ask specific questions regarding reporting suspicious injuries.6 Although it is overwhelming to imagine that so much abuse occurs, statistics show that it does occur not only with children but with adults and our elderly population.

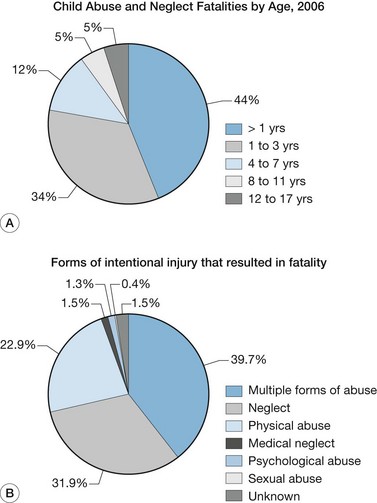

Intentional injuries can occur in the form of neglect, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and emotional abuse. All of these injuries can occur independently but they often occur simultaneously.7 Neglect is the most common form of intentional injury. Of the average 5.5 million referrals made to Child Protective Services each year, 64.5% of these children are neglected.8 Physical abuse occurs in 25% of intentional injury cases.8 More than 15% of victims of abuse suffer more than one type of abuse and more one-third of child fatalities are attributed to neglect (Fig. 61.1).9 Burn injury is frequent in both neglect and physical abuse of children. Severe burns in children are between 10% and 12% of all intentional injuries.10

(From: Child Welfare Information Gateway: June 2008 Numbers and Trends, Child Abuse and Neglect Fatalities: Statistics and Interventions. Online. Available at: www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/factsheets/fatality.cfm).

Since the last edition of this book, intentional injuries to adults have increased. It is frequently debated within the literature as to whether the increase is a valid increase or if there is an increase in reporting. Violence specifically against women and young girls has now become a universal phenomenon. The World Health Organization reported that of the women who were partnered at some point during their lifetime, 15–71% reported experiencing physical or sexual violence by their partner.11 Within this realm of violence against women and young girls, acid violence is the worst form of violence and violation of human rights.12 Though steps are being taken to control the widespread free sale of acids to the public,13 this act of violence is still on the rise and warrants discussion in the burn care literature and sensitivity to this overwhelming problem by all burn care professionals. Another vulnerable population of intentional burn injuries are the elderly. In the past 10 years, burns in the elderly have increased secondary to increase in size of the aging population.

Prevalence rates of intentional burn injuries

Despite the improvement and use of smoke detectors, investment in sprinkler systems and improvement in building codes in developing countries, burns continue to cause significant intentional and unintentional injuries. Smoking remains the leading cause of death by fire. Cooking is the number one cause of residential fires. Annually, fire-related injuries claim more than 300 000 deaths and 10 million ‘disability-adjusted life years’ worldwide.13 Middle and low-income countries exceed 95% of fire-related burns.13–15 Approximately half of these countries are in southern parts of Asia.15 In the USA, burn injuries result in approximately 1 million emergency department visits and 50 000 hospital admissions, with a 5% mortality rate.13 Fire and burns represent 1% of the incidence of injuries. Fatal home injury burns and fire deaths rank fifth and third, respectively in the USA.16 The incidences of the causes of burns are: flame/fire 46%; scalds 32%; hot objects 8%; chemicals 3%, and other forms 6%. Fires/burns occur frequently in the home 43%; street/highway 17%; occupational 8%, and other 32%.17 Burn injuries inflicted in Pakistan occur mostly to adult women: approximately, one-third are secondary to stove burns and 13% are acid burns. Husbands inflict more than 52% of these injuries and in-laws one-quarter of the injuries.18 Victims who are at highest risk of fire-related injuries and deaths are children ≤4; adults over 65 years; African-Americans and Native Americans, and the poor or those living in rural areas.16 A literature review of hospital-based studies of the prevalence of burn injuries in China, revealed similar results with children < 3 years more vulnerable; males more than females; those living in a rural setting, and incidence occurring between the hours of 17:00 and 20:00.19

Prevalence of childhood burns

Over the past 50 years, child abuse has been documented especially in the USA. Child abuse characteristics are composed of physical abuse, neglect, sexual abuse, psychological abuse and other, which include Munchausen by proxy and abandonment. Child abuse may present with multiple characteristics. Major forms of injuries to children include falls, poisonings, car accidents, foreign body and fires/burns.20 Ten percent of child abuse is burns and 20% of burns are child abuse.21 The child abuse death rate in the USA is approximately 1000 children annually,18 with burns and scalds as the most frequent cause of death.10 In China, the mortality rate from abuse ranges from 0.49% to 3.14%. In Hong Kong, it is 2.3%; in Singapore 4.61%, and in Iran 6.4%.19 The lowest rates are in the UK and the highest rates are in the USA, where the majority of the studies have been completed.10 In many cases of burn injuries, it may be difficult to conclude if the burn injury is an incidence of neglect, intentional or truly an accidental event.4 More recent studies10,21–23 have begun to analyze hospital cases of burns to delineate if intentional or non-intentional. The characteristics of types of burns include scalding (70%); flame burns (50%), or electrical (3–4%).19 Bathtub submersions peak at 6–11 months, then again at 12–14 months and remain high until 33–35 months of age.20 Most studies calculate the mean ages of children with intentional burns from 2 to 4 years of age.18 Boys are 2–3 times more afflicted than girls with the youngest of multiple siblings suffering most often.21 There is no ethnic predilection. Of children who are victims of physical abuse 10–12% suffer severe burns.10 In 2007, Hicks and Stolfi24 concluded children with burn injuries are at risk for occult fractures at a significant rate. Therefore, a skeletal survey should be routine in burn patients presenting to the emergency department, as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Men are convicted at a greater rate than female perpetrators, despite an equal rate as perpetrators.25

Prevalence in elderly

Over the past 10 years, prevalence data of burns in elderly has increased secondary to recent emerging studies in this area. As in pediatric burns, geriatric burns are higher in the developed countries at a rate of 20%, yet in the developing world it is 5%.15 Results of the review of data from the US National Burn Repository demonstrated an increase in rate of elderly abuse from 1991 to 2005.15,26 Of those burned, 14% are over 55 years of age (with 6.2% between 55–64 years; 3.3% between 65–74 years, and 4.4% >75 years of age). There is a male predominance of burns of 1.4 : 1. However, this decreases with age and is thought to be secondary to the decrease in life expectancy of males to females. The most common injuries are flame burns, accounting for 37%, and scalds at 22%. The total body surface area (TBSA) was 9.6% and the majority of injuries were residential.15,26 In the UK, residential settings are the leading site for burn injuries to the elderly at a rate of 18.6%. The occurrences had a 32% higher mortality rate and 33% more TBSA affected than like-sized burns in aged patients from other causes than abuse. Over a 4-year period, Bortolani and Barisoni27 investigated 53 patients aged ≥60 years who were admitted to a local Italian hospital. It was noted 85% of these burns occurred in the home and 11% in nursing homes. Flame burns were the most common at 55%. The incidences were attributed to pre-existing diseases in 85% of patients. These diseases included cardiovascular accidents, neurological problems and diabetic comas.27 In addition to illness, lack of adequate supervision is another major etiology for burns in this age group.18 In the USA, residential care settings accounted for one-fifth of geriatric burns.28

With increase in an aging population, there is concern about an increase of domestic elderly abuse and proportionately an increase in burn victims.29,30 In the USA, elderly physical abuse was underreported, with a rate of 2.8% of total cases of abuse in 1988. However, in 1996, residential institutions estimated only one-fourth to one-fifth of abuse was reported. Another study, from Canada, estimated the prevalence of abuse at 1%.28 The abuse is usually kept secret owing to guilt, shame and fear of reprisal, especially if the perpetrator is the victim’s adult child (Box 61.1).

Box 61.1 Premorbid indicators of intentional burn injuries of adults

• Accessibility as a target for abuse as in institutional living or living with a ‘caretaker’

• Caretaker(s) with a history of substance abuse, and/or other psychopathology

• An injury that is not consistent with the story described

• Conflicting reports of the injury

• Scalds with clear-cut immersion lines and no splash marks

• Scalds that involve the anterior or posterior half of an extremity and/or the buttocks and genitals, or a flexion pattern

• Other physical signs of abuse/neglect

The literature reports controversial results on the most likely perpetrator, spouse vs adult children. As in child abuse, disabled adults and those who suffer from dementia are at higher risk for abuse. Drugs and alcohol abuse in caretakers also increase the rate of abuse. Other characteristics in caregivers are mental disorder, financial difficulties and deviant behavior.28

Distinctive characteristics of perpetrators and families

Perpetrators are frequently individuals responsible for the care and supervision of their victims. In 2007, one or both parents were responsible for 69.9% of child abuse or neglect fatalities.31 More than one-quarter (27.1%) of these fatalities were perpetrated by the mother acting alone.31 Child fatalities with unknown perpetrators accounted for 16.4% of the total.31 According to the National Child Abuse and Neglect data system in 2008, 56.2% of perpetrators were women and 42.6 % were men and 1.1 % were unknown.32 Of the reported women perpetrators 45.3% were younger than 30 years of age compared to 35.2% of men younger than 30.32 These percentages have remained consistent for several years in a row. Some 61% of all perpetrators were neglected as children.1,31,32 Approximately 13.4% of all perpetrators were associated with multiple types of abuse.1,31–33 Ten percent of perpetrators experienced physical abuse as children and 6.8% were sexually abused as children.33 Of the children who are abused, 80% were abused by their parents.31–33 Other relatives accounted for an additional 6.5%.31–33 Unmarried partners of parents were 4.4% of perpetrators. Of those parents who were perpetrators, more than 90% were biological parents, 4% were step-parents and 0.7% were adopted parents.32,33

Other characteristics of perpetrators include being commonly adolescent parents, single parents, often maintaining inconsistent expectations for a child’s development, experiencing a lack of external supports, stressors such as substance abuse, poor education (no high school diploma), unemployment, poor housing, mental illness, and being reliant on children for emotional support (Box 61.2).34 Most fatalities from physical abuse are caused by fathers or other male caregivers. Mothers are most often held responsible for deaths resulting from child neglect.35 In some situations there are two ‘perpetrators’, i.e. the actor and the overtly passive observer who does not stop the abuse.36 Justice and Justice,37 in their work with families who mistreat children, identified several erroneous belief systems that are commonly held by perpetrators; these are listed in Box 61.3. Since, as most authorities believe, violence is a multi-generation intra-family pattern, then it is likely that the belief systems attributed to child perpetrators can be extrapolated to perpetrators of adult abuse as well.36

Box 61.2 Risk factors for abuse/neglect by burning

Forced-immersion demarcation

• Symmetrical, mirror image burn of extremities

• Glove-like (burned in web spaces)

• Clear line of demarcation, crisp margin

• Doughnut-shaped scars on buttocks/perineum (spared area forcibly compressed against container, decreasing contact with hot liquid, if container is not a heated element)

• Flexion burns, ‘zebra’ demarcation to popliteal fossa, anterior hip area, or lower abdominal wall

• Injuries of restraint (e.g. bruises mimicking fingers and hands on upper extremities).16

Injury demarcation, other

• Incongruent with history of event

• Pattern of household appliance – note whether even pattern versus brushed, imperfect mark

• Location of injury: palms, soles, buttocks, perineum, genitalia, posterior upper body

• Cigarette burn, if more than one on normally clothed body parts and if impetigo ruled out.

History of injury

• Evasive, implausible explanation

• Incompatible with child’s developmental age

• Changes in story; discovered to be burned – rule out dermatologic epidermolysis bullosa (EB), dermatitis herpetiformis, chemical burn due to analgesic cream, phytophotodermatitis,17 and birth marks, including Mongolian spots18

• Under-supervised – inadequate monitoring, impaired person supervising, inordinately young babysitter (<12 years of age)

• Burn is older than history given

• Water outlet temperature greater than 120°F

• Mechanism of burn is incompatible with injury (e.g. exposure time, history of event, and degree of burn are inconsistent)

• Patient’s per-event behavior displeasing to caregiver (e.g. inconsolable, failed to meet caregiver’s expectations)

• Toileting events related to history of injury19

Developmental associations

• Pre-verbal, non-verbal person

• Vulnerable person (e.g. special need, failure to thrive, elderly)

• Caregiver expectations are inconsistent with patient’s development; caregiver overestimates child’s developmental skills and safety knowledge; caregiver unaware of patient’s developmental capacity

• Patient has symptoms of mental disorder (e.g. ruminating, aggressive)

• Patient displays disturbing behaviors related to attachment (e.g. excessive crying, clinging, apathy/lethargy, excessively withdrawn, listless, unemotional, submissive, polite, fearful, vacant stare)

• Hyper-sexualized language or behavior, as compared to same age peers.

Caregiver–patient relations

• History of interrupted caregiver–child bonding

• Adolescent caregiver(s) (e.g. child–child versus adult–child interactions)

• Strained interactions; inappropriate expectations of the patient by the caregiver

• Role reversal (rely on patient for support)

• Inappropriate or lack of caregiver concern:

Other physical signs of abuse or neglect

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree