Infestations, Stings, and Bites Melissa E. Cyr Insect infestations, stings, and bites are quite prevalent throughout the world. Infestations occurring in indoor dwellings and insects living in temperate climates can cause problematic bites throughout the year, and may produce a vast array of clinical manifestations. Human and animal bites occur less frequently; however, they still have the potential to produce significant morbidity and mortality.

SCABIES

Scabies is a highly contagious, common parasitic infection, characterized by intense itching and superficial burrows. It is caused by the microscopic mite Sarcoptes scabiei. Scabies infections affect both males and females of all socioeconomic and ethnic groups. Transmission most often occurs through direct skin-to-skin contact, with a higher incidence occurring through prolonged contact within households or neighborhoods. For this reason, outbreaks are common in extended-care facilities, prisons, child care facilities, and schools. Less frequently, the mite is transmitted by indirect contact through fomites, and can live for up to 3 days on inanimate objects like bedding or clothing.

Pathophysiology

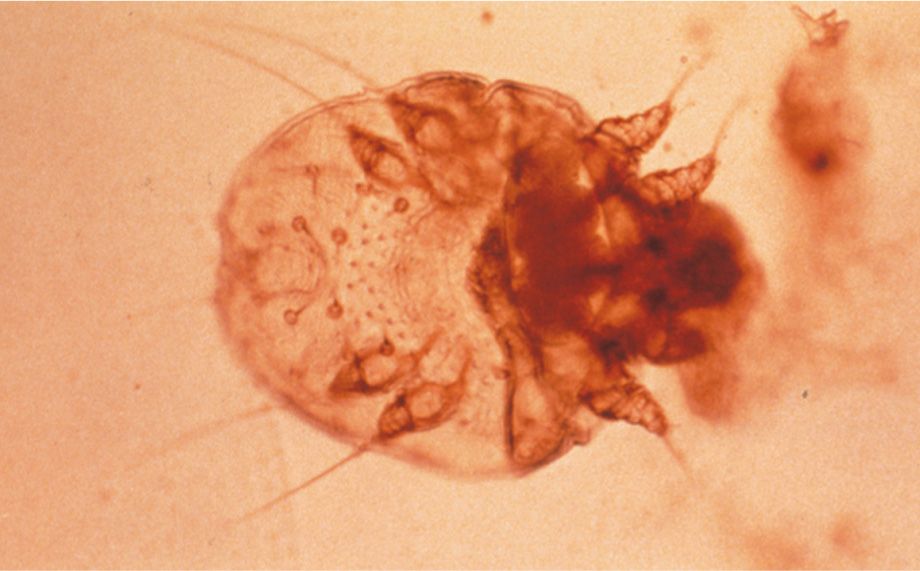

The adult mite that affects humans is female, approximately 0.3 to 0.4 mm long, and has a flattened, oval body with four pairs of legs (Figure 13-1). The infestation begins when the fertilized female mite burrows into the skin and moves linearly beneath the most superficial layer of the epidermis (stratum corneum), depositing eggs and fecal pellets (scybala) along the way. These deposited eggs hatch, and within several weeks, larvae grow into adult mites, capable of reproducing and perpetuating the infestation cycle.

After approximately 1 month, an allergic reaction (delayed-type IV hypersensitivity reaction) occurs in response to the mites, eggs, and scybala, transforming the initial, minor, localized itching into severe and widespread pruritus. Subsequent scabies infections in a sensitized individual can produce generalized pruritus more rapidly because of this hypersensitivity response.

FIG. 13-1. Scabies mite.

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation varies based on the type and location of lesions. Symptoms begin insidiously and are often mistaken for skin conditions such as dermatitis. Widespread pruritus is common, and severe nocturnal pruritus is the hallmark characteristic of scabies infection. Light pink curved or linear burrows, occasionally seen with a black dot on one end representing the mite, are pathognomic but not always seen. Scratching the area can destroy burrows (Figure 13-2), displace mites, and promote the spread of mites to other locations on the body.

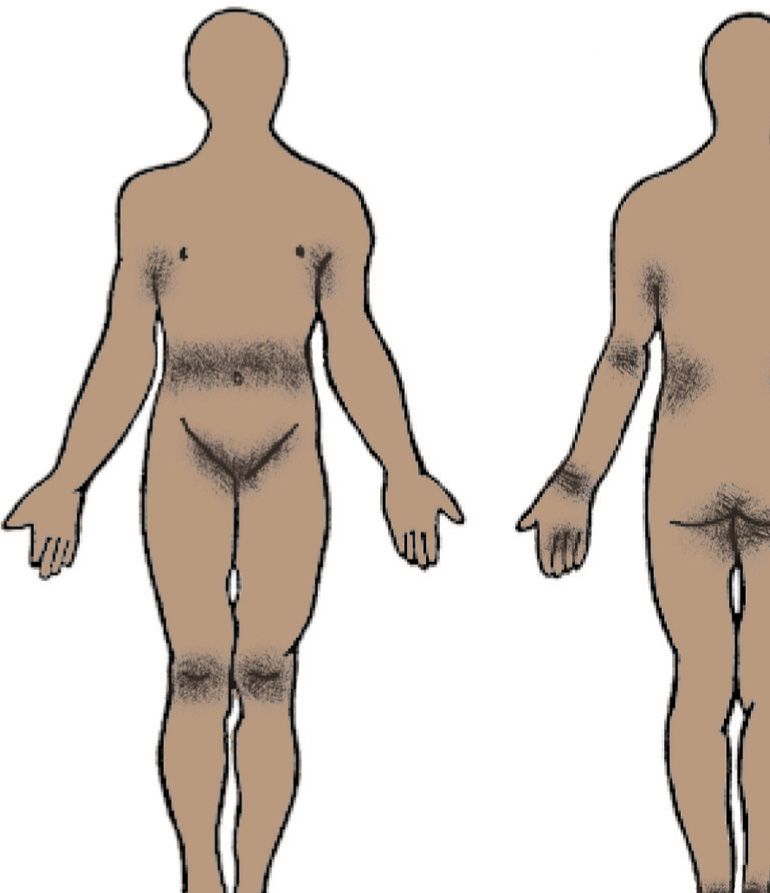

Older children and adults commonly present with red papules and vesicles that can be seen in the finger webs, wrists, lateral aspects of feet and hands, waist, axillae, buttocks, penis, and scrotum (Figure 13-3). Infants and small children may develop pustules on the palms and soles, and in some cases the head and neck. A good rule of thumb is to always suspect scabies on men with pruritic papules on the scrotum or penis (diaper area for children) or nipple region in women. Nodules on the trunk and axillae may erupt as a result of the host’s exuberant immune response to the scabies.

Crusted (Norwegian) scabies

Crusted scabies (also called hyperkeratotic or Norwegian) is severe and less common than general scabies infection. Patients at risk are the immunocompromised, elderly, and/or mentally or physically disabled. Compromised immunity, along with decreased itch sensation, leads to the infestations of hundreds to millions of mites. These patients classically present with asymptomatic, hyperkeratotic crusting on the palms and soles, thickened (dystrophic) nails, thick crusts and gray scales on the trunk and extremities, and verrucous (wart-like) growths in areas of trauma (Figure 13-4). Hair loss may also be present. Mites involved in crusted scabies are not more virulent than those found in traditional scabies infection; they are present in massive numbers. Individuals infected are highly contagious and therefore require quick and aggressive medical treatment.

FIG. 13-2. Scabies linear rash.

FIG. 13-3. Scabies distribution.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Scabies |

• Pruritus (generalized or prolonged)

• Dermatitis

• ID reaction

• Folliculitis

• Psoriasis (crusted scabies)

• Arthropod bites (i.e., bedbugs)

• Dermatitis herpetiformis

• Varicella

• Bullous pemphigoid (urticarial phase)

Diagnostics

The diagnosis of scabies may be based on clinical suspicion. A definitive diagnosis is often made through identification of mites, feces (scybala), eggs, or egg casings under microscopy by performing a mineral oil mount (see chapter 24: Mineral Oil Prep).

Management

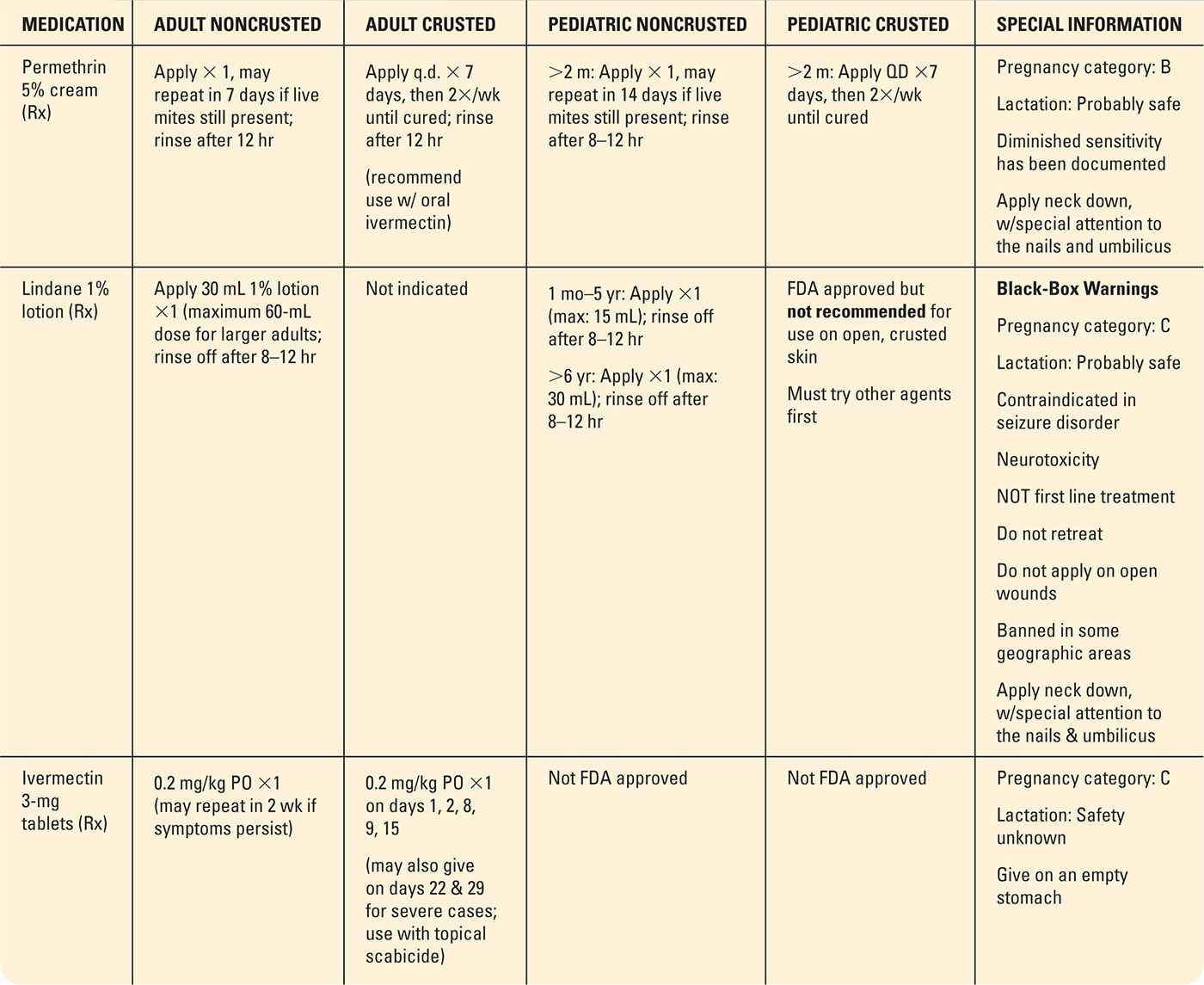

Management of scabies requires both pharmacologic treatment and environmental eradication. Topical permethrin 5% cream is the treatment of choice (Table 13-1). Many of the topical treatments available are generally effective after one application; however, a second treatment after 1 week is common. Several second-line therapies are available, including topical sulfur 10% lotion and crotamiton 10% lotion, which has a higher failure rate of 40%.

Warning: Lindane 1% topical application, once considered the treatment of choice, is now FDA approved only for use in individuals who failed appropriate doses of other approved therapies or are intolerant to other treatments, in view of its neurotoxic side effects. In 2009, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended that lindane not be used for children even as a second-line therapy. The state of California banned the use of lindane because of its reported neurotoxicity and environmental hazards.

FIG. 13-4. Norwegian scabies.

Oral ivermectin, an antihelminthic agent, has been used off label for effective treatment of scabies with concurrent use of a topical scabicide. Ivermectin tablets, available in 3 mg, are dosed 200 µg per kg and may be repeated in 2 weeks. It should not be used in children under 5 years of age. Ivermectin is very effective in scabies epidemic and immunocompromised patients. Treatment for Norwegian scabies may require 200 µg per kg dose on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15 and further doses on days 22 and 29, if severe.

Patients should be instructed on the appropriate application of topical scabicides. It is important to bathe prior to application, which is generally recommended at bedtime. Ensure fingernails are trimmed and clean. Apply topical scabicide to all skin from the neck down, ensuring all skin folds are treated, including finger and toe webs, under the fingernails, axillae, umbilicus, and the anal and vaginal clefts. Inadequate coverage is the primary cause of treatment failure. In infants, covering their hands with mittens helps prevent removal and ingestion of the product. If infection of the face or scalp is suspected, such as the case with infants or crusted scabies, also treat the skin above the neck, avoiding the eyes and mucous membranes. If the scabicide is washed off or removed prior to the required treatment duration, reapply more.

Once the recommended application time has lapsed, the patient may wash off the topical scabicide using soap and warm water. It is important to stress that only clean towels, clothing, and linens should be used to decrease reexposure. Members of the same household, including intimate contacts, should be treated empirically with topical scabicides at the same time as the infected patient. All clothing, bedding, and towels in contact with infected skin must be washed and dried on the hottest possible settings. Items unable to be washed may be sealed in a plastic bag for at least 1 week. Floors and chairs should be cleaned and vacuumed, while pets do not require treatment. Children may return to school and adults to work the day after treatment. Schools and workplaces may require a written statement from the patient’s health care provider.

Crusted scabies is more challenging to treat because of the thick, hyperkeratotic scale, making it difficult for topicals to penetrate and kill thousands of mites. Combination therapy with topical permethrin and oral ivermectin is frequently used. Despite treatment with scabicides, inflamed pustules, erosions, and crusts may occur secondary to scratching. Pruritus associated with hypersensitivity to mites can last for up to 2 to 4 weeks after effective treatment.

Prescribed Medications for Treatment of Scabies |

Special Considerations

Pediatrics: Infants have widespread skin involvement more often than adults with a different distribution and presentation. Delay in diagnosis is often the result of treating other diagnoses of pruritus, such as eczema. Infants and children may present with more scaly papules and vesicles especially in occluded areas such as the axillae and diaper region. Involvement of the face and scalp (especially the occipital area) are seen more frequently in children than in adults. Application of permethrin to infants more than 2 months old should include the scalp, head, neck, trunk, and extremities. Parents should be given careful instruction to avoid the eyes. Make sure that the permethrin is applied to the palms and soles, interdigital areas, umbilicus, folds of skin (inguinal, neck, axillary, etc.), and periungual areas. The use of lindane in infants is not recommended in view of increased risk for toxicity. Acropustulosisofinfancy (API) is associated with scabies infection, and presents with itchy vesicles or pustules on the palms and soles in children up to age 3 years (Figure 13-5). Symptoms usually occur after a history of scabies infection and are usually misdiagnosed as a recurrence. These findings represent an allergic response to the scabies mite and not a current infection. There are no burrows seen in API. However, clinicians should be prudent and perform a mineral prep to ensure the child has not been reinfected. Specific treatment of API is often not warranted, unless lesions are extremely pruritic. With appropriate scabies treatment, pustules will flatten gradually and resolve over a few months.

Pregnancy: There are no adverse effects of scabies in pregnancy; however, treatment options for scabies during pregnancy should be limited to topical permethrin (pregnancy category B). Ivermectin and lindane are not recommended for use in pregnancy.

Geriatrics and immunosuppression: The initial presentation of scabies in the elderly or immunosuppressed patient very often yields fewer cutaneous lesions than younger or otherwise healthy adults, and is more consistent with nonspecific dry, scaly skin that may have several nodules. Severe pruritus, however, is often still observed. In these populations, the face and scalp may also be involved. As mentioned previously, Norwegian or crusted scabies is seen increasingly in these populations. Transmission of scabies is greatest in those living in close contact, and through sharing clothing and bedding. Assisted care personnel or facility administration should be notified so that other residents may be screened and measures taken to avoid an outbreak.

FIG. 13-5. Acropustulosis of infancy.

CLINICAL PEARL

Inflammatory nodules on the genitals are considered scabies until proven otherwise, so always examine the genitals in suspected scabies cases.

Prognosis and Complications

Patients with scabies infections have an excellent prognosis with proper treatment. Postscabetic pruritus, associated with a hypersensitivity response, is common and may persist for weeks after treatment, despite scabies eradication. Properly treated patients should begin to show steady improvement in pruritus after about 2 to 3 weeks. Symptoms are typically managed with oral antihistamines (e.g., cetirizine, loratadine, or hydroxyzine) and topical corticosteroids. Short courses of oral corticosteroids are generally reserved for severe and intractable cases.

Secondary infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes may occur. Antibiotic use should be considered as indicated.

Referral and Consultation

Referral to dermatologist or an infectious disease specialist may be considered if the patient shows no improvement with sufficient treatment after 3 to 4 weeks. Consultation may be considered earlier in patients who are immunosuppressed with disseminated infection. A skin biopsy may be attained if the diagnosis is questionable or no response to treatment.

Patient Education and Follow-up

Patient education is an important step to successfully treating scabies infection. Patients should be educated not only on application technique of antiparasitic medication but also on household management of inanimate objects since mites can live up to 3 days off a human host. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has up-to-date information on prevention, control, and institutional spread. Patients can be reassured that after full treatment they are able to return to school and work and resume normal social interactions.

PEDICULOSIS

Pediculosis, commonly known as lice, is a contagious type of parasite that feeds on human blood. Infestation occurs through close personal contact, as well as through inanimate objects, such as brushes, combs, hats, clothing, and bedding. Lice infestations have become an increasing problem throughout the world, and usually occur with crowded living conditions or poor hygiene. In endemic areas, body lice are capable of transmitting infectious diseases such as typhus, relapsing fever, and trench fever.

Pathophysiology

Lice are parasites that live on the skin of their host. They feed on human blood approximately five times per day by piercing the host’s skin and injecting saliva, causing a pruritic response. Without feeding, adult lice are able to live off of a human host for approximately 10 days, and up to 3 weeks as eggs or nits. Some experts use the term eggs to describe the container for a developing louse nymph and refer to ‘nits’ as the empty egg casing, whereas other experts refer to “eggs” and “nits” interchangeably; the latter reference is the context to which it will be referred to in this text.

Lice are small (<2 mm or about the size of a sesame seed), flat, and wingless insects that crawl and do not hop or fly. After feeding, they appear on human skin as characteristic rust-colored flecks. Pets cannot transmit human lice infestations, as these lice affect humans only.

Clinical Presentation

Head lice

Pediculus humanus capitis, or head lice infestation, can affect any part of the scalp, with accompanied dermatitis commonly seen on the occipital scalp, neck, and behind the ears (Figure 13-6). Nits are attached to the base of the hair with a glue-like substance secreted by the louse, within approximately 3 to 4 mm of the scalp. Occasionally, eyelash involvement occurs, presenting with redness and localized edema. Pediatric patients and their caregivers or household members have the highest prevalence of head lice, and girls are affected more than boys. It is seen across all ethnicities, but notably less in African Americans. After approximately 3 to 8 months of infestation, sensitization to lice can cause pruritus and posterior cervical adenopathy. Subsequent scratching of the scalp increases patient risk for bacterial infection, inflammation, pustules, and crusting.

Body lice

Caused by Pediculus corporis, body lice is an uncommon parasitic infestation associated with poor hygiene and the spread of infectious diseases. They do not live directly on the body; rather, they reside and lay their eggs in seams of clothing and return to the skin surface to feed only, making direct visualization for diagnosis difficult. Like head lice, hypersensitivity occurs over time, leading to pruritus and risks of secondary bacterial infection.

FIG. 13-6. Nits.

Pubic lice

Pediculus pubis or pubic lice received its nickname “crabs” based on its short, broad body with large front claws resembling a crab (Figure 13-7). Pubic lice are highly contagious, and sexual exposure with an infected partner yields a high rate of transmission. These patients are therefore more likely to be at increased risk for coinfection with other sexually transmitted disease. Pubic hair is the most common site of infestation; however, heavy infestation may occur in the perianal, proximal thigh, abdominal, axillae, and facial hair. Pruritus is a common symptom, along with a crawling sensation in affected areas. Inflammation and adenopathy can occur with regional infestation.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Pediculosis |

• Psoriasis

• Dermatophyte infection

• Seborrheic dermatitis

• Contact dermatitis

• Folliculitis

• Drug reactions

• Delusions of parasitosis

• Arthropod bites or other parasitic infestations, such as scabies

• Systemic causes of generalized pruritus

Diagnostics

Scalp and pubic lice are easier to diagnose through direct visualization, or with the aid of a magnifying glass. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, the gold standard diagnosis is observing a live, moving louse on the scalp or pubic area; however, this is difficult as they move quickly and try to avoid light (Frankowski & Bocchini, 2010). A fine-toothed “nit” comb may be utilized to aid in diagnosis by combing the hair with teeth touching the scalp in a downward pattern near the crown to remove nits and live lice. In general, the closer the nits are to the scalp, the more recent the infection. However, the presence of nits may not indicate active infestation, as they may be retained on the shafts of hair for months after successful treatment. Dandruff or other hair debris may be easily misdiagnosed for nits or egg casings; however, generally hair debris is not as tightly adhered to the hair shaft as are nits. Utilizing a Wood’s lamp may facilitate diagnosis as nits containing an unborn louse fluoresce white and empty nits fluoresce gray. Body lice may also be visualized on seams of clothing and may actually be seen crawling.

FIG. 13-7. Crab louse.

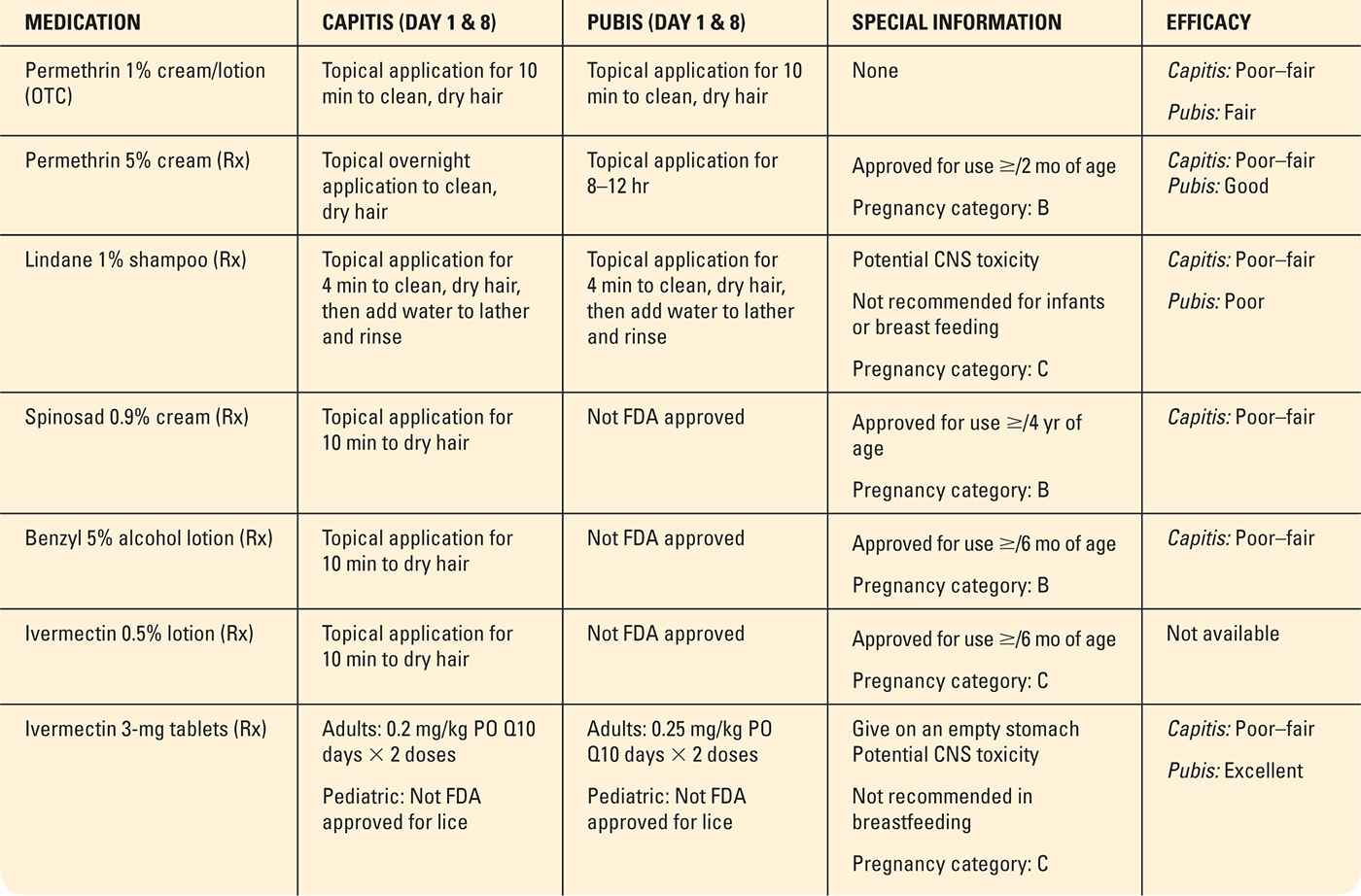

Management

To avoid overtreatment and risks, treatment for pediculosis should only be initiated when a skilled professional has made a definitive diagnosis. Treatment of lice and nits must include both topical therapy and environmental control measures. Unfortunately, the availability of over-the-counter topical antipediculide medications, along with improper diagnosis, has led to documented resistance in the United States to all topical medications used to treat lice, including permethrin, pyrethrin, and lindane. The choice of topical is predicated on the clinician’s awareness of resistance in their communities. Pediculicides treat both lice and nits, and should be reapplied after 1 week. Patients using pediculicides on their hair should rinse off over a sink and not a shower, to reduce skin exposure.

Treatment for head and pubic lice is similar (Table 13-2). Various nonmedical methods of management are discussed under “Patient Education” below. The CDC recommends environmental treatment measures for cases of body lice, which include removing infested clothing and laundering with hot water (at least 130°F). Medical treatment and improved hygiene practice will usually resolve infestations. Clinicians should consider prophylactic treatment of household contacts, including sexual partners.

There are many traditional therapies that are not evidence-based or required to meet FDA approval, but are commonly used by patients and some providers. The application of a dilute white vinegar solution to the hair is used to soften the “cement” of the nit on the shaft and has been reported to make nit removal easier. During outbreaks at schools and daycare, many parents apply a thick, occlusive substance (petrolatum, mayonnaise, olive oil) to children’s hair in an effort to smother the nit and prevent nit adherence to the hair shaft. Wet combing may be performed at home using a high-quality, commercially available nit comb, as an alternative to or in addition to topical pesticide medications. And even more drastic measures include shaving or cutting their children’s hair in an effort to eradicate the lice infestation. Parents can become frustrated and embarrassed by lice infestation, and are anxious to reach a quick resolution. Shaving or cutting a child’s hair is not recommended as there can be associated psychological implications, especially in young girls.

Medication Options for Pediculosis Capitis and Pubis |

Adapted from Bolognia, J. L., Jorizzo, J. L., & Schaffer, J. V. (2012). Dermatology (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders.

Special Considerations

Pediatrics: School nurses play an important role by screening pediatric populations for infestations and providing education to reduce transmission. Valuable public health measures may be implemented if an outbreak is suspected, such as storing clothing (e.g., hats and scarves) separately. Some schools may implement “no nit” policies, requiring students to refrain from school based on the presence of nits alone. The American Public Health Association does not support this practice because the presence of nits alone does not make the child contagious. In some school districts, students may return to school after completing wet combing or appropriate insecticide. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics (2010), however, diagnosing a child with active head lice means it is likely the child has been infested for at least 1 month by the time it is discovered, and therefore poses little risk to other students from infestation; students are encouraged to attend classes, but maintain distance from other students until adequately treated. Eyelash infestation with head and pubic lice is seen primarily in the pediatric population and may cause secondary complications, such as infection or eye lid dermatitis. Presence of pubic lice infestation of the eyelashes or eyebrows may be a sign of possible sexual abuse.

Pregnancy: During pregnancy, pharmacological treatment options are limited. Special attention should be made when selecting an appropriate treatment. Table 13-2 lists options available for treatment during pregnancy, and other, nonpharmacological methods may also be utilized, as described under Management.

Geriatrics: There are no special considerations for elderly patients.

Prognosis and Complications

Prognosis is excellent since symptoms should completely resolve with successful treatment. Potential complications may include secondary bacterial infection from scratching, or hypersensitivity reaction. Large, live, moving lice suggest reinfestation, whereas lice of different sizes suggest treatment resistance, and patients should be reevaluated.

Referral and Consultation

Similar to scabies, recalcitrant cases should be reevaluated for the correct diagnosis. Patients who are immunosuppressed or have disseminated symptoms may be referred to a dermatologist or infectious disease specialist.

Patient Education and Follow-up

Environmental measures are important to treat lice and control outbreaks. Carpeting, mattresses, car seat, and furniture should be vacuumed. Bedding and clothing, including hats, should be laundered on a weekly basis. Brushes and combs should be washed in hot water (>130°F) or thrown away. A fine-toothed comb should be used once weekly for several weeks after treatment to confirm successful treatment. There are various commercial businesses and salons that provide lice and nit removal services, which may be an option to patients who do not feel comfortable with or are otherwise unable to perform their own combing treatments.

Follow-up is not generally warranted unless the patient experiences continued symptoms despite adequate treatment, or if they develop any complications such as a secondary bacterial infection.

TICK BITES

Ticks are nonvenomous, bloodsucking, external parasites which can harbor various infectious diseases. There are two distinct classifications of ticks: soft-bodied ticks (Argasidae) and hard-bodied ticks (Ixodidae). Hard-bodied ticks are vectors for more serious infectious diseases; they feed on their hosts much longer (up to 10 days) and are generally much more difficult to remove. Ticks feed by first using their curved, sharp mouth parts to bite and then secrete a glue-like substance to help adhere to their host. The bite itself is often painless and can go unnoticed, especially if in an inconspicuous area. Ticks generally wait on bushes and tall grass for a host to pass by, or are transmitted by pets bringing ticks into the home. Lyme disease and Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF) are the two most common tick-borne infectious diseases in the United States.

Lyme Disease

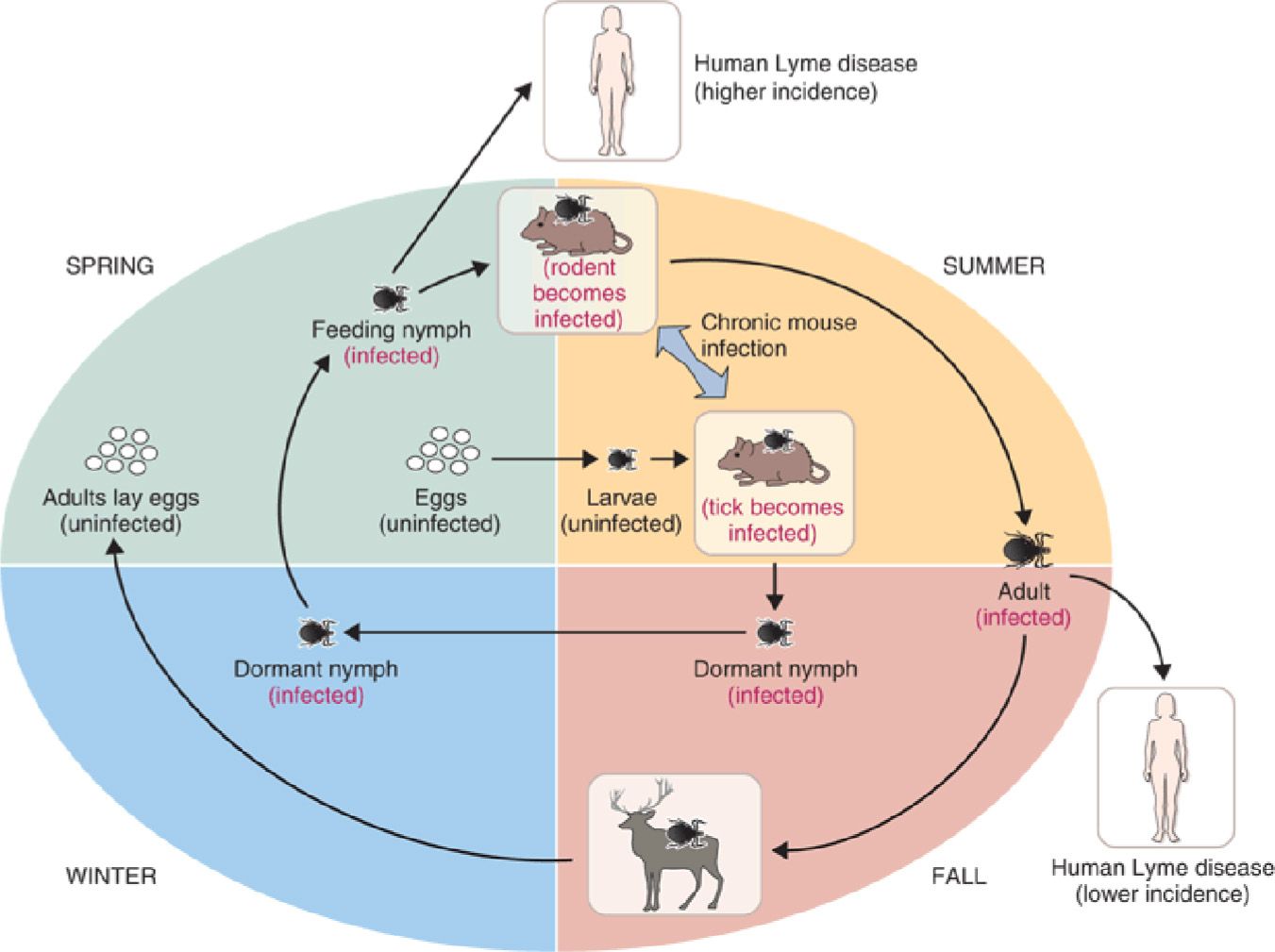

Lyme disease, caused by Borrelia burgdorferi in the United States, is a bacterial spirochete infection transmitted through deer ticks (Ixodes scapularis), and is the most common tick-borne disease in the United States and Europe (Figure 13-8). White-tailed deer, white-footed mice, as well as other mammals and birds, are important disease reservoir hosts on which these ticks feed during their 2-year life cycle (Figure 13-9). Deer ticks in the United States are also responsible for the transmission of at least three different species of Borrelia, babesiosis, and human granulocytic anaplasmosis.

FIG. 13-8. Adult deer tick.

Lyme disease has been reported all across the country, particularly in and around coastal New England, including Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut; other coastal states including New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, and Pennsylvania; and Minnesota and Wisconsin. While infection may occur at any time of year, risk is highest during the summer or early fall due to increased tick exposure. Aside from living in endemic areas, individuals who have outdoor hobbies, such as hiking or camping, or an outdoor occupation, such as forest rangers, are at highest risk. Children are also at high risk because of increased outdoor activity.

FIG. 13-9. The life cycle of I. scapularis (deer tick). Deer ticks are the arthropod vectors that transmit the spirochete B. burgdorferi to humans, causing Lyme disease.

Physical Characteristics of I. scapularis |

Nymph | Tiny and round Often compared to a poppy seed in size and appearance |

Adult | Approximately 3 mm in length Four pairs of legs Color ranging from primarily black to orange-reddish depending on sex |

Engorged | Large, globular-shaped abdomen The abdomen will be a light grayish-blue color |

Pathophysiology

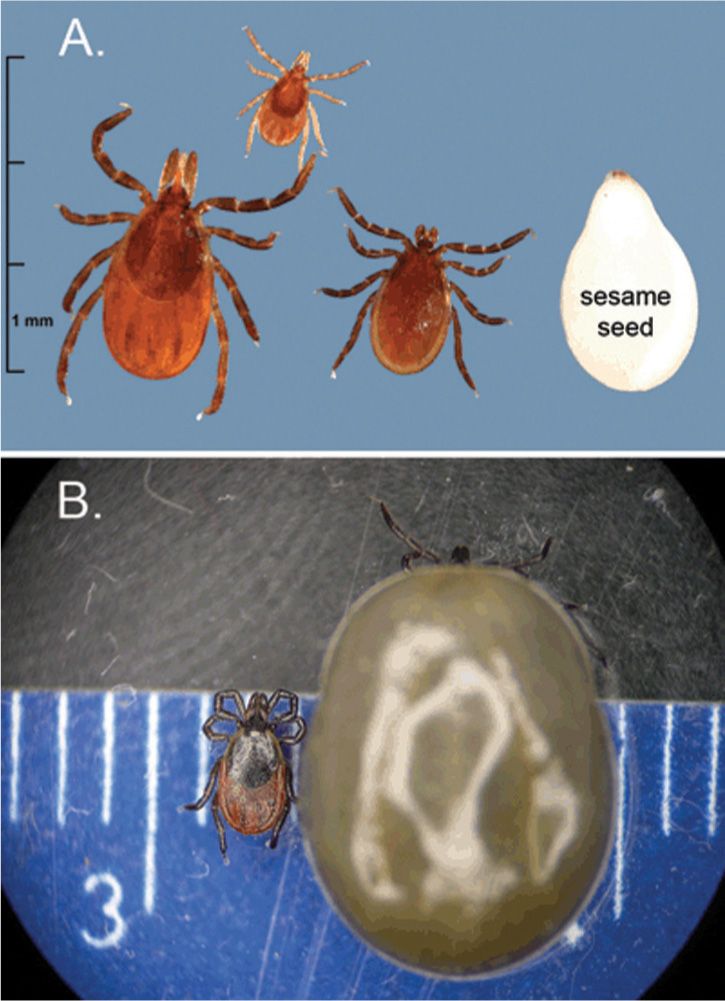

The deer ticks’ life cycle evolves from larvae, to nymphs, to adulthood. Tick size and appearance may provide helpful clinical clues for the experienced clinician to distinguish this from other arthropod or other tick bites (Table 13-3). Both nymphal and adult ticks are capable of transmitting infection. Figure 13-10 shows hard ticks capable of transmitting disease in the United States, including I. scapularis, associated with the transmission of Lyme disease; Dermacentor variabilis, associated with the transmission of RMSF; and Amblyomma americanum, associated with the transmission of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis, tularemia, and Southern tick-associated rash illness, or STARI, which is not covered in this text. Feeding ticks are firmly attached to the skin (Figure 13-11). If the tick is small and walking on the skin surface, it is incapable of transmitting Lyme disease. The presence of an engorged tick embedded in the skin, or once it has detached after feeding, yields a higher risk of disease transmission. The duration of the tick’s attachment is important when evaluating the risk of disease. Transmission of the disease rarely occurs within the first 48 hours of attachment in unengorged ticks (Hu, 2013). Time recollection may be difficult for patients while eliciting history, so it is often helpful to ask about all recent possible exposures.

FIG. 13-10. I. scapularis. A: Unfed adult female (left), nymph (middle), and adult male (right). B: Unfed (left) and fully engorged adult female (right).

Clinical presentation

Early detection of Lyme disease can be a challenge since only about 30% of patients have a known bite. Symptoms can be very subtle and often attributed to a brief viral illness, never suspecting a tick-borne illness.

Lyme disease may be localized to the skin or may involve multiple organs such as the joints, heart, and nervous system depending on the stage of infection. The three stages of infection discussed here are summarized in Table 13-4.

CLINICAL PEARL

Lyme disease is an important differential diagnosis for patients presenting in the summer with flu-like symptoms and no cough.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS | Lyme disease |

• Other tick-borne diseases

• Meningitis

• Joint disorders

• Dementia or delirium

•

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree