85

Infantile Hemangiomas and Vascular Malformations

• Vascular anomalies, which often present at birth or during early infancy, are classified into two groups based on their biologic and clinical behavior:

– Vascular malformations that result from defective vascular morphogenesis.

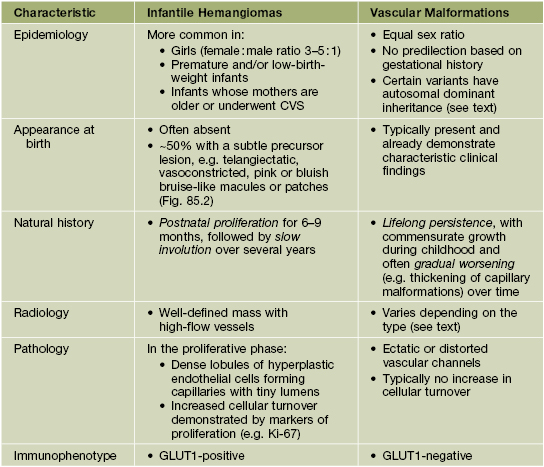

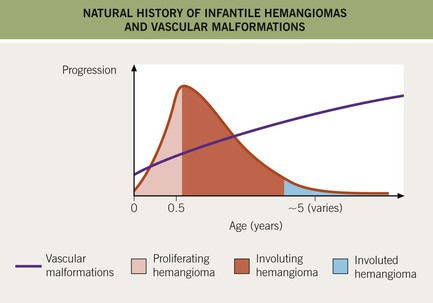

• Features that distinguish IHs from vascular malformations are presented in Table 85.1, and differences in their natural histories are depicted in Fig. 85.1.

• Additional vascular neoplasms are discussed in Chapter 94; other vascular ectasias, such as telangiectasias and angiokeratomas, are covered in Chapter 87.

Infantile Hemangioma (IH)

• Benign vascular neoplasm that represents the most common tumor of infancy.

– Affects ~5% of infants, with a predilection for girls and premature neonates (see Table 85.1).

• IHs appear during the first few weeks of life, with a characteristic course:

– Subsequent involution gradually over several years (e.g. 30% completed by 3 years of age and 50% by 5 years), with softening and a duller or lighter color followed by flattening (Fig. 85.3).

– Some IHs involute with little or no visible sequelae, whereas others (especially pedunculated or exophytic lesions) leave atrophic, fibrofatty, or telangiectatic residua in addition to scars at sites of previous ulceration (discussed later; Fig. 85.4).

Fig. 85.4 Residua of infantile hemangiomas. A Superficial hemangioma with a healing ulcer in an infant. B Hypopigmentation (arrows) and a circular scar at the site of the previous ulcer in the same patient 20 years later. C, D Residual telangiectasias. E Atrophy and fibrofatty changes. A, B, E, Courtesy, Ronald P. Rapini, MD; D, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

• Divided into three clinical subtypes based on the depth of cutaneous involvement:

– Superficial lesions (~50%; upper dermis) are bright red with a finely lobulated surface (‘strawberry’ hemangiomas) during proliferation, changing to a mixture of purple-red and gray during involution (Fig. 85.5).

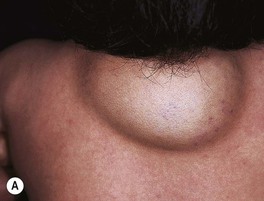

– Deep lesions (~15%; lower dermis and subcutis) present as warm, ill-defined, light blue-purple, rubbery nodules or masses (Fig. 85.6); often become evident later and proliferate ~1 month longer than superficial lesions.

• IHs have two major distribution patterns:

– Focal lesions arise from a localized nidus (see Fig. 85.5A).

– Segmental lesions cover a broader area or developmental unit and are more likely to be associated with regional extracutaneous abnormalities – e.g. PHACE(S) and LUMBAR syndromes (discussed later) (Fig. 85.7).

Fig. 85.7 Segmental infantile hemangiomas. A Segmental facial hemangioma mimicking a capillary malformation. B Thicker segmental facial hemangioma partially obstructing the visual axis. Both of these patients had PHACE(S) syndrome. C Segmental lumbosacral hemangioma. This child is at risk for LUMBAR syndrome. A, Courtesy, Maria Garzon, MD; B, C, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• DDx: precursors and early lesions: capillary malformation, telangiectasias; well-developed lesions: pyogenic granuloma, other vascular tumors, venous/lymphatic malformation, and rare entities such as nasal glioma and soft tissue sarcomas (see Table 53.1); multiple lesions: glomuvenous malformations, blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome, multifocal lymphangioendotheliomatosis with thrombocytopenia, ‘blueberry muffin baby’ (see Chapter 99).

Complications of IHs

• Ulceration: occurs in ~10% of lesions, especially those on the lip and in the anogenital region or other skin folds, at a median age of 4 months (Fig. 85.8); whitish discoloration of an IH in an infant <3 months of age may signal impending ulceration; results in pain, a risk of infection (relatively uncommon), and eventual scarring (see Fig. 85.4A,B).

Fig. 85.8 Ulcerated infantile hemangiomas. A Ulcerated hemangioma on the buttock. Because the hemangioma component may not be obvious, this diagnosis should be considered when an infant presents with an ulcer in the diaper area. B Ulcerated superficial hemangioma above the ear. Note the distortion of the pinna. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Disfigurement and interference with function due to the IH’s location and/or large size.

– Periocular IH – risk of astigmatism if puts pressure on globe, amblyopia if obstructs the visual axis, and strabismus if affects orbital musculature (see Fig. 85.7A,B); requires ophthalmologic evaluation.

– IH on nasal tip, columella, or lip (especially if crosses the vermilion border) – high risk of distortion of facial structures (as well as ulceration if on the lip) (Fig. 85.9).

– IH on breast (in girls) – may affect underlying breast bud, so early surgery should be avoided.

• Associated extracutaneous abnormalities.

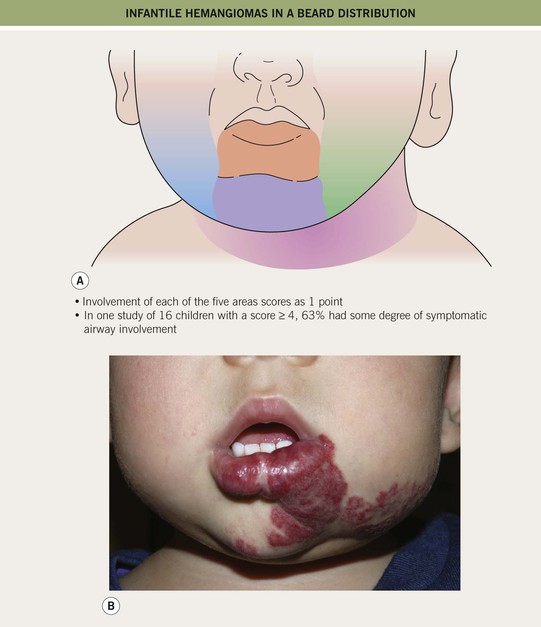

– IHs in ‘beard’ area of the lower face – often associated with airway IHs, which may present with noisy breathing or biphasic stridor; otolaryngologic evaluation is needed for infants with symptoms or when the IH is likely to be actively proliferating (i.e. <4–5 months of age) (Fig. 85.10).

Fig. 85.10 Infantile hemangiomas in a ‘beard’ distribution. A Anatomic sites associated with risk of an airway hemangioma. B Infant with a laryngeal hemangioma in addition to cutaneous lesions in a ‘beard’ distribution. A, Adapted with permission from Orlow SJ, Isakoff MS, Blei F. Increased risk of symptomatic hemangiomas of the airway in association with cutaneous hemangiomas in a ‘beard’ distribution. J. Pediatr. 1997;131:643–646; B, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

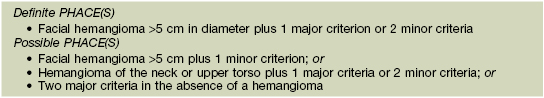

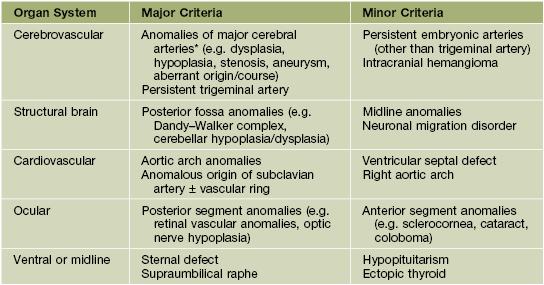

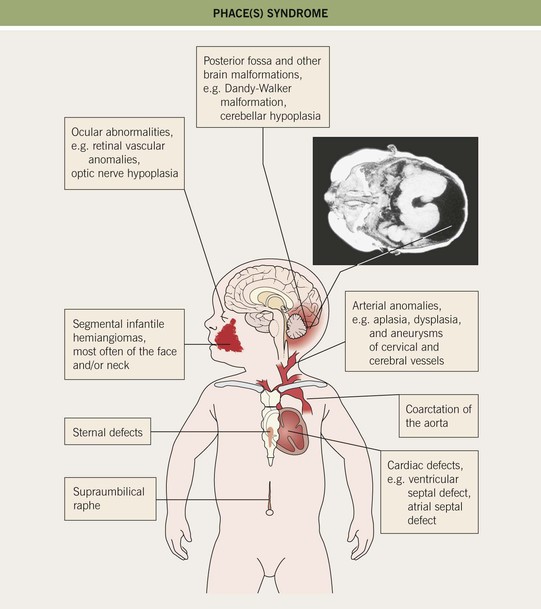

– Large facial IHs, particularly segmental lesions – risk of PHACE(S) syndrome: P, posterior fossa malformations; H, hemangioma; A, arterial abnormalities (cervical, cerebral); C, cardiac defects, especially coarctation of the aorta; E, eye anomalies; S, sternal defects and supraumbilical raphe (Table 85.2; Figs. 85.11 and 85.12; see Fig. 85.7A,B).

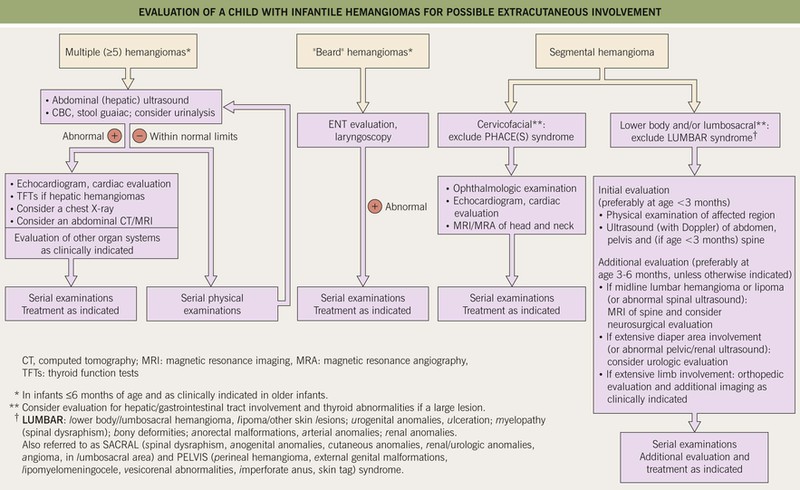

Fig. 85.12 Evaluation of a child with infantile hemangiomas for possible extracutaneous involvement. See Fig. 85.11 and Table 85.2 for additional information on PHACE(S) syndrome.

–

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree