div class=”ChapterContextInformation”>

9. Adherence in Acne

Keywords

AcneAdolescentTreatmentTopical therapyRetinoidAntibioticIsotretinoinAdherenceIntroduction

Acne vulgaris is chronic inflammatory skin disorder with complex pathogenesis [1]. Disease pathophysiology is multifactorial with hyperseborrhea and dyseborrhea, altered keratinization of the sebaceous duct, Cutibacterium acnes (C. acnes) colonization, and inflammation all playing an important role [1]. Hormones contributing to the development of acne include androgens, insulins, and insulin-like growth factor-1. Adding to the complexity are alterations in sebum production, hypersensitivity to androgen production, and inflammatory cytokines affected by the innate immune system. Targeting the various pathogenic factors is one of the general principles of acne treatment, and is the reason why multiple acne treatments exist [2]. Treatment of acne is complex, ranging from various topical to oral agents, and more recently new devices and laser treatments [2].

Acne affects more than 85% of teenagers and the disease may continue into adulthood. While not life threatening, acne is linked with negative impact on quality of life (QOL) and self esteem [3]. Various factors such as one’s ethnic background, personality, sex, age, severity of disease, and presence of scarring determine the impact on QOL. In a recent cross-sectional, case-control study assessing QOL and self-esteem in 100 acne patients, 58% of the cases had medium-to-high impairment in QOL according Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI). This study also identified that the QOL impairment worsens as disease severity increases [4]. Nevertheless, while acne can have a major impact on QOL, patients still may not use recommended treatment.

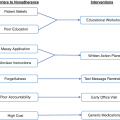

Adherence to even simple acne regimens is poor; adherence to more complex regimens is worse [5]. Low adherence to treatment in the adolescent population is highly prevalent. Special approaches may be needed in this patient population to promote good adherence to treatment. This chapter will evaluate the prevalence of nonadherence in acne, analyze nonadherence among different acne treatments, and discuss interventions to improve adherence.

Prevalence of Nonadherence in Acne

Prevalence of nonadherence in acne patients

Study | Sample size | Measure of adherence | Key results |

|---|---|---|---|

Miyachi et al. [7] | N = 428 | Self-reported | 76% of subjects reported poor adherence. Adherence to topical medication was poor in 52% of those treated with a topical agent (N = 123), and in 49% of subjects taking combination therapies (N = 275). |

Hester et al. [9] | N = 24,438 | The adherence rate was measured using MPR; the MPR was dichotomized to categorize patients as adherent (≥0.8) or nonadherent (<0.8) | 89% of subjects were under the age 18. Only 12% of the patients were adherent! In children and adolescent medicaid patients with acne, only 4% of children and 13% of adolescents were adherent. |

Huyler et al. [16] | N = 84 | Self-reported | Among the 84 patients recommneded OTC benzoyl peroxide by their physician, only 36% of patients included an OTC recommendation when recounting treatment plan verbally. |

Biset et al. [52] | N = 67,657 | Adherence was measured according to the MPR; patients were considered adherent if MPR was ≥0.8 | 46.1% of patients receiving isotretinoin had MPR ≥ 0.8. This percentage decreased as the number of attempts increased (29.8% for the second attempt and 19.8% for more than two attempts). |

Filling the prescription is only the first step. Patients still need take their medications as directed by a healthcare provider. Secondary nonadherence refers to patients not using their prescriptions as instructed, missing doses, or discontinuing therapy early. In a survey of 428 acne patients, 76% of subjects reported poor adherence. Adherence to topical medication was poor in 52% of those treated with a topical agent only (n = 123), and in 49% of subjected taking combination therapies (n = 275). Patients who reported a good understanding of acne and its treatment were more likely to have good adherence [7].

In a retrospective cohort study evaluating acne medication adherence in 24,438 patients Medicacid patients, of whom 89% were under the age of 18, only 12% of the patients were adherent! Patient’s age, gender, number of drug refills and number of drug classes used are the main factors associated with adherence [8]. In children and adolescent Medicaid patients with acne, only 4% of children and 13% of adolescents were adherent [9].

Other issues with adherence to acne treatments which can all lead to treatment failure, include adherence decreasing over time, drug holidays in which patients go several days or more without taking medication, misunderstanding how the medication is supposed to be used, and overusing medications. A study analyzing data from MarketScan database differentiated acne treatment adherence to specific medication classes. Oral therapies (retinoids, 57%; antibiotics, 4%; contraceptives, 49%, glucocorticoids: 2%) had better adherence than topical formulations (retinoids, 2%; antibiotics, 4%; and glucocorticoids, 2%) [10]. Better adherence to treatment regimens results in improved clinical outcomes. To address the insufficient treatment response of acne patients, it is worthwhile to evaluate patient adherence before switching treatments or adding to the complexity of the patient’s treatment.

Nonadherence to Topical Therapy

Topical Retinoids

First generation all-trans retinoic acid (tretinoin) and third-generation (adapalene and tazarotene) topical retinoids serve as the cornerstone for treatment of comedonal and inflammatory acne [2]. Retinoids are anti-inflammatory, comedolytic, and resolve the precursor lesion. These medications enhance any topical acne regimen and are ideal for comedonal acne [11]. In the study of Japanese patients with acne, topical retinoids were prescribed in 47% of the patients, with a higher likelihood of use in males (54% vs 44%, respectively); however, the use of topical retinoids increased with increasing severity of acne (40% with mild acne to 52% with severe acne) [7].

Common reasons for premature discontinuation of retinoids are irritation with initial use of medication, lag time until patients see improvement, and the complexity of treatment regimens [12]. In addition to taking some time to work, the disadvantage of topical therapy is that it can be laborious and time-consuming for patients [13].

Topical Antibiotics

Commonly prescribed topical antibacterial agents include clindamycin, erythromycin, and dapsone. Clindamycin and erythromycin provide coverage against Staphylococcus aureus and C. acnes [2]. These agents are effective first-line treatments for mild-to-moderate acne, but are not recommended as monotherapy due do the risk of developing antibiotic resistance. They are commonly prescribed with benzoyl peroxide to decrease this risk. Adverse effects of clindamycin and erythromycin may include dermatitis, folliculitis, photosensitivity reaction, pruritus, erythema, dry skin, irritation, and Clostridium difficile-associated colitis [11]. Adherence to daily application of topical antibiotic agents is as low as 45% [14]. Above-mentioned side effects may lead to poor tolerability of recommended treatment, which has been suggested to reduce patient’s adherence. To further investigate this, one study identified 35 studies evaluating tolerability of topical antibiotics in acne treatment. There was no significant correlation between tolerability and discontinuation when assessing the number of discontinuations caused by tolerability across these studies [14]. Common reasons for unintentional nonadherence to topical antibiotics included forgetfulness or lack of knowledge. Patients may also intentionally not adhere to their topical treatment believing their condition may have improved.

Benzoyl Peroxide

Benzoyl peroxide (BP) has bactericidal activity against C. acnes through bacterial oxidation, anti-inflammatory properties, and weak activity against comedones [15]. While, current acne treatment guidelines incorporate BP as an important component, acne patients have poor adherence to BP [11, 16]. Adherence to topical 5% BP ranged from 14–79% when measured using electronic monitoring [17]. A prospective cohort study of 84 patients assessing adherence to physician recommended OTC BP revealed that only 36% of patients included an OTC recommendation when recounting their treatment plan verbally [16].

Salicylic/Azelaic Acids

Salicylic and azelaic acid are OTC acne products, which can be used in combination with other drugs for the symptomatic treatment of mild-to-moderate acne. These treatments may cause side effects that lead to poor adherence, such as excessive erythema, scaling, pruritus, burning, dryness, irritation, and dermatitis [11]. However, a cross-section, Web-based survey of US females ages 25–45 revealed that salicylic acid was the most frequently used (34% of survey respondents) OTC treatment across all racial/ethnic groups [18].

Nonadherence to Systemic Therapy

The treatment of acne often requires more than topical therapy. The systemic medications used in acne management include oral antibiotics, hormonal agents, and oral isotretinoin [11]. Adherence to oral isotretinoin is higher compared to systemic antibiotics and hormonal agents [8, 17, 19].

Patients with acne were more adherent to isotretinoin (71%) than to non-isotretinoin treatments (35%). Another study assessing adherence to isotretinoin estimated adherence rate of approximately 87.5% during the initial course and 60.5% during subsequent courses [10]. Isotretinoin causes many bothersome side effects; while one might predict that side effects would reduce adherence, the presence of bothersome side effects might help prevent patients from forgetting to take the medication. Another possibility is that improved isotretinoin adherence may be attributable to the strict requirements of the iPLEDGE program patients and providers must follow for isotretinoin therapy. The iPLEDGE is a special restricted distribution program approved by the Food and Drug Administration to minimize fetal exposure due to the teratogenic potential of isotretinoin ; during treatment, patients are required to have monthly follow-up visits [11].

Interventions to Improve Adherence

Studies reporting adherence intervention in acne patients

Study | Sample size | Intervention to increase adherence | Therapy | Length | Measure of adherence | Adherence result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Yentzer et al. [25] | N = 26 | Combination therapy once daily versus daily application of 2 separate medications | Combination group: Clindamycin phosphate 7.2% / tretinoin 0.025% gel; control group: Clindamycin phosphate gel 1% and tretinoin cream 0.025% | 12 weeks | E-monitoring using MEMS caps | Adherence was 88% in the combination group and 61% in the control group (p = 0.02) |

Yentzer et al. [41] | N = 20 | Intervention group received internet-based survey as a weekly reminder vs. no reminder in the control group | Daily topical benzoyl peroxide 5% gel | 12 weeks | E-monitoring | Median adherence was 74% in the internet group vs. 32% in the control group (p < 0.01) |

Yentzer et al. [41] | N = 61 | Patients randomized into 4 groups: Standard of care, frequent office visits, daily phone call reminders to patients, daily phone call reminders to patients’ parents | Once daily topical therapy | 12 weeks | E-monitoring | Median adherence was 82% for frequent office visits, 59% for standard of care, 48% for phone calls to patients, and 36% for phone calls to patients’ parents |

Boker et al. [39] | N = 40 | Intervention group received twice daily text message reminders while the control group did not receive text messages | Clindamycin 1%/benzoyl peroxide 5% gel in the mornings and adapalene 0.3% gel nightly | 12 weeks | E-monitoring | Mean adherence was 33.9% in the reminder group and 36.5% in the control group (p = 0.75) with similar clinical improvements in acne severity |

Sandoval et al. [32] | N = 17 | Intervention group received demonstration on how to use medication vs. control group that received no demonstration | Adapalene/benzoyl peroxide gel once daily | 6 weeks | E-monitoring | Median adherence rates were 50% in the sample group compared to 35% in the control group (p = 0.67) |

Fabroccini et al. [40] | N = 160 | Intervention group received smart phone text messages while control group received no texts. | 12 weeks | Self-reported | Adherence improved from 4.10 to 6.6 days per week in the text-message group, and 4.3 to 4.9 in the control group (p < 0.0001) | |

Navarette-Dechent et al. [33] | N = 80 | Providing a written plan/written counseling in addition to oral counseling in the intervention group vs. oral counseling only in the control group | Combination of topical and systemic therapy | 6 months | Self-reported | Adherence was 80% in the intervention group vs. 62% in the control group |

Myhill et al. [34] | N = 97 | Intervention group received supplementary patient education material (SEM) vs. control group vs. standard-of-care patient education (SOCPE) vs. SOCPE + more frequent office visits | Adapalene 0.1% / benzoyl peroxide 2.5% gel once daily | 12 weeks | E-monitoring | Adherence was greatest in the SEM group with a mean of 63.1% (p = 0.0206). Adherence in the SOCPE group and SOCPE plus additional office visits group was 48.2% and 56.5%, respectively |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree