Resources, and how they are utilized within a system or process of care, influence outcomes

Bailey described quality improvement as ‘a broad range of activities of varying degrees of complexity and methodological and statistical rigour, through which healthcare providers develop, implement and assess small-scale interventions, identify those that work well, and implement them more broadly, in order to improve clinical practice’ [5]. All stakeholders, including healthcare professionals, patients, their families, researchers, payers, planners, administrators and educators, may affect the changes that will lead to improved patient outcomes, better system performance and improved professional development [6].

Quality improvement may be applied in a macro-, meso- or microsystem, and can therefore be undertaken settings such as a small clinic, a unit, an operating room, an entire hospital, a group of hospitals, a university division or department, a provincial or national system, or even via an International organization.

- 1.

Access: Patients should have timely care at the appropriate setting by the appropriate healthcare provider.

- 2.

Efficacy: Patients should receive healthcare that is evidence-based.

- 3.

Safety: Patients should receive care that does not harm them.

- 4.

Patient-centric: Care delivery should consider the preferences and values of individuals.

- 5.

Equity: Care should be of a consistent standard irrespective of patient demographics, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, geographic origin, etc.

- 6.

Efficiency: Healthcare should continuously evaluate its processes to reduce waste of resources, time and investment.

- 7.

Appropriately resourced: The system should continuously evaluate its supply of providers, funding, information, equipment and facilities to meet its needs.

- 8.

Integrated: Each component of the healthcare system should complement the others to optimize healthcare delivery.

- 9.

Promoting population health: Healthcare systems should effectively treat and prevent illness and promote healthy lifestyles of all the people it serves.

Traditionally, most systems have placed the emphasis on safety and efficacy, while efficiency and equity are less frequently prioritized. Streamlined and reliable processes are less expensive to maintain than less efficient ones that might involve errors and rework. Quality improvement might aid an organization to avoid costs associated with failing processes, errors and sub-optimal outcomes. Quality improvement incorporates proactive processes that recognize problems before they occur, and is engaged in effective methods of reporting errors, addressing them if they do occur. Quality improvement involves the engagement of relevant stakeholders and as such, stimulates improvements in communication and might increase effective partnerships and funding opportunities [7].

- 1.

Obtain a thorough understanding of the system or process.

- 2.

Maintain the focus on patient care.

- 3.

Encourage teamwork. Processes are frequently complex, involve more than one discipline or work area, and solutions often require creativity and sustainable staff engagement. Quality improvement will thus be facilitated because it is frequently multiple, iterative experiments of change. Although these teams may have often worked together in the past, QI initiatives often bring different teams together or encourage new approaches within stagnating teams.

- 4.

Acquire and continuously evaluate reliable data. We must be able to distinguish between what is believed to be happening and what is actually happening, have reliable baseline and ongoing data, be able to monitor fidelity of the intervention, intervene if there are unintended consequences, and be able to demonstrate when change leads to an improvement. This will also ensure the sustainability of the intervention and allow translation to and comparison across sites.

Prominent differences between Quality Improvement (QI) and traditional research

Quality improvement | Traditional research | |

|---|---|---|

Primary goal | Improvement in local process or outcome | Generalizable knowledge |

Cycle time | Rapid iterative tests of change | Longer data collection, definitive results |

Context | Embraces context to allow for sustainability | Attempts to eliminate the impact of context; does not consider sustainability |

Data analysis | Statistical control (Shewhart) and run charts; implicit; accept consistent bias | T-tests, p-values, chi-square and deviations; explicit; adjust for bias |

Risk | Minimal risk. Ethics board review often not required; refer to ARECCI tool | May be some risk. Formal ethics board review required |

Sample size | ‘Just enough’ data | ‘Just in case’ data |

Examples of methods | Model for improvement, LEAN, Six Sigma | Randomized controlled trials, retrospective chart reviews |

Hypothesis | Flexible | Fixed |

Protocol | Adaptable; new tests of change | Strict adherence |

In order for scientific knowledge to take hold, one needs to thoroughly understand the context in which it is being applied. If this context is variable, its effect may be difficult to understand. As a result, one needs to understand the traditions, culture, habits and processes of those who are likely to implement the intervention. Special forms of measurement are required to determine whether the intervention has been successful or that the change is in fact an improvement. For example, evidence-based interventions may be applied more or less effectively depending on the manner in which they are implemented. For example, standardization, education or forcing functions may be more appropriate in different contexts. The five knowledge systems involved in improvement, as proposed by Betaldien and Davidoff [6], include the available scientific evidence, context awareness, performance measurement, plans for change and execution of planned changes. QI is best implemented in an environment where its initiatives are supported by institutional leadership, is realistic given environmental and resource-related factors, and is well aligned with the organization’s strategic objective. Quality improvement specialists have produced guidelines, referred to as the Squire guidelines, to assist in reporting initiatives in a scientific manner that is suitable for publication [4, 8].

In addition to reinforcing a change in culture, the science of QI provides tools to more effectively facilitate your efforts. Some of the structured improvement methods include the ‘Model for Improvement’, ‘Six Sigma’ and ‘Lean’. Each of these methods offers evidence-based methods to achieve success in quality improvement. Each model reflects a common thread of analysis, implementation, and review, but focuses on different types of change concepts. There are two major quality improvement methodologies that specifically aim to evaluate processes. Lean methodology emphasizes the elimination of waste, and therefore the improvement of flow, by removing process steps that add little value, and improves the connections between these steps. Six Sigma , on the other hand, aims to improve quality by reducing variation. Lean is usually best applied to high-volume or frequent processes, while any process may be amenable to evaluation by Six Sigma. Both interventions are usually concluded within a few months. Lean is usually more ad hoc in nature, with minimal formal training required, while Six Sigma usually involves dedicated resources and broad-based training.

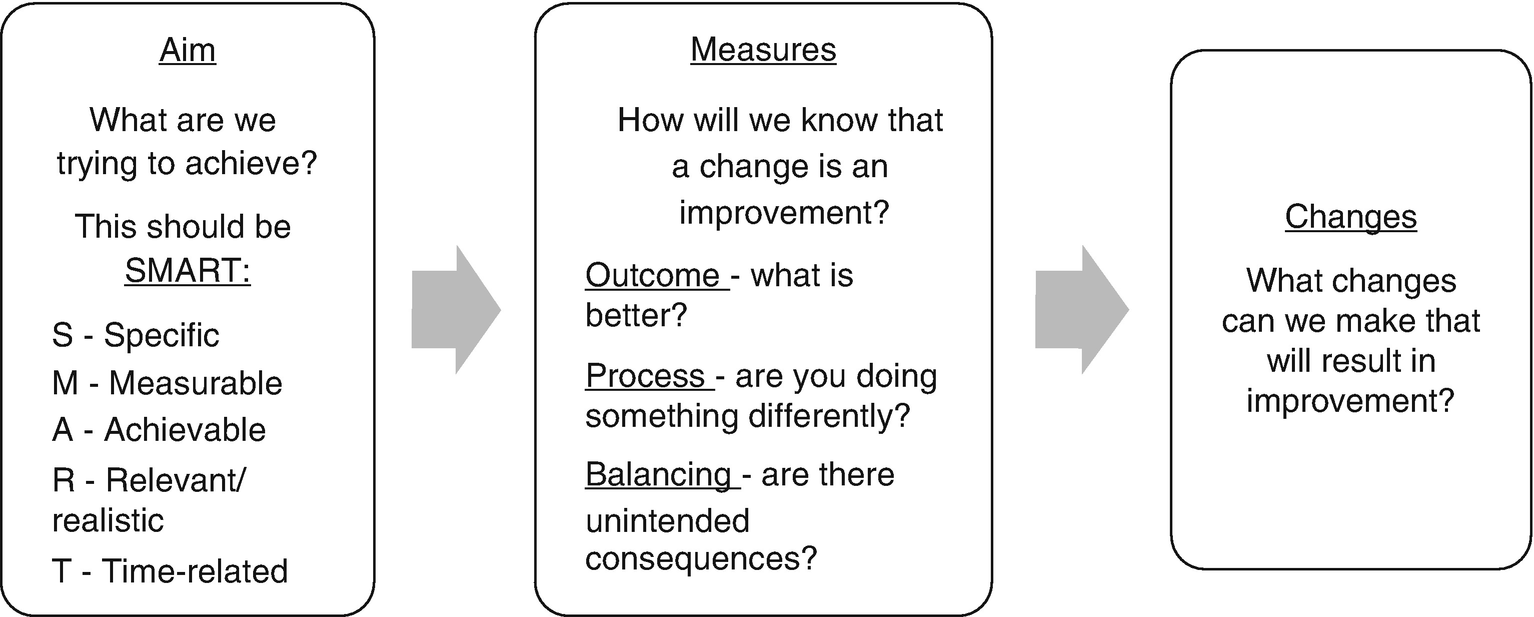

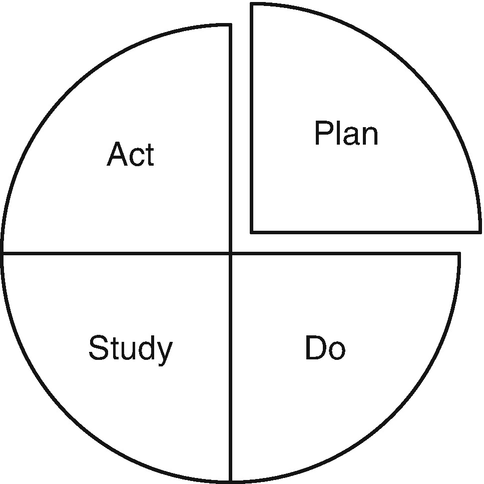

The ‘Model for Improvement’ approach

PDSA Cycles. Plan a change; Do the test of change; Study the results; Act on the results

Selected quality improvement tools to evaluate a system or process

Tool | Applications | Example |

|---|---|---|

1. Fishbone/Ishikawa diagram | Brainstorming strategy which assists to laying out all the possible causes |

|

2. Five Why’s | Assist in performing a root cause analysis |

|

3. Process mapping | Visually represents the steps undertaken during a process |

|

4. Pareto charts | Causes are charted to identify the prominent reasons |

|

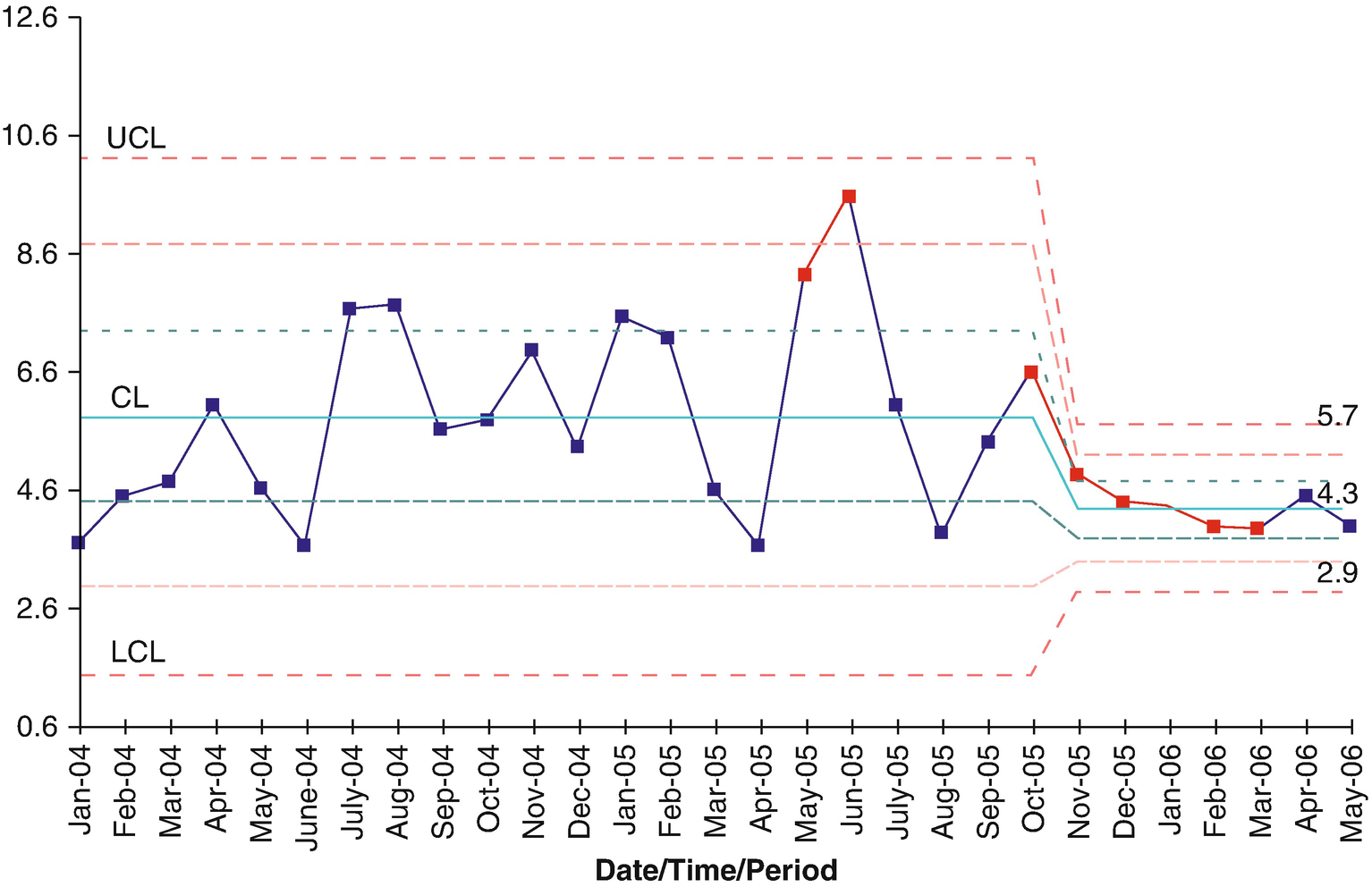

A statistical process control chart demonstrating falls per 1000 patient days in a burn centre. The special cause variation is demonstrated in red: firstly, where two consecutive points fell beyond two standard deviations; and secondly, where six consecutive points were seen to decrease

In addition to courses offered by organizations such as the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI), there are an increasing number of university certificate, diploma and master’s degree programmes offering training in quality improvement and patient safety. This is in line with increasing recognition of its contribution to delivering quality healthcare, and QI is becoming a fundamental component of strategic priorities for high performing healthcare organizations.

Individuals with quality improvement training and experience add value in a variety of contexts within the hospital and specifically in burn units. In addition to undertaking quality improvement initiatives, some of the tools for which have been outlined earlier in this chapter, these individuals are frequently engaged in risk management and other patient safety related hospital functions. Examples of these include the assessment, prevention and management of medical errors, adverse events, and complications as diverse as infections, communication issues, medication errors, as well as surgical and diagnostic considerations. Quality improvement experts, either internal or external to the organization, may recommend a diverse range of solutions for safety-related issues incorporating, amongst other strategies, information technology, reporting, culturally sensitive programmes, training and educational initiatives, accreditation, workforce assessment and engagement solutions [9–11]. They are also well placed to implement processes for incident reporting, and are frequently called upon to facilitate and modernize clinical meetings such as those dedicated to discussing mortality and morbidities, and to obtain consensus for best practices [12–14].

Increasingly, governmental agencies and medical insurance services internationally are insisting that health services maintain outcome and process measures so that performance can be linked with payment and resource allocation. As in other surgical specialties, burn centres have begun to focus on a series of quality improvement indicators in their field. The involvement of burn surgeons (and professions allied to medicine) in activities of their various affiliations has undoubtedly been of value, as for example has been the impact of the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) on the process of QI applied to the practice of burn surgery [15].

8.3 Quality Improvement in Burn Care

Most of this textbook describes systems and processes relating to the quality care of patients with thermal injuries, incorporating prevention, acute management and rehabilitation. The authors have recommended, based on their expertise and the available evidence-base, how best to approach specific clinical scenarios. Quality improvement strategies are widely applicable to the care of patients with burn injuries, and a comprehensive review of the range of quality improvement interventions applied to the practice of the care of the burn injured patient would be impossible to limit to this chapter.

That being said, there remains a relative dearth of quality improvement interventions in the burn literature, using QI methods. As mentioned previously, quality improvement initiatives described for publication are distinct from traditional research publications and have different objectives. Unfortunately, quality improvement manuscripts submitted for publication are usually evaluated through a traditional research lens. In line with burn organizations’ increasing requirement for quality improvement to form part of verification processes of burn centres, and the limited number of reviewers able to assess quality improvement submissions, there is considerable need to roll out quality improvement training amongst burn care practitioners. There are, however, a few prominent individuals, including Bessy and Gibran [16, 17] and other members of the American Burn Association (ABA) especially, who have made significant strides in advancing quality improvement as it applies to the delivery of burn care [18–24], and this culture has spread to other national and international burn organizations. Guidelines for the optimal care of patients with burn injuries have been published by several organizations, including the International Society for Burn Injuries (ISBI) .

Quality improvement is nothing without reliable acquisition and evaluation of data. The nature of burn care is such that the best conclusions about clinical practices can often only be made by collecting data across regions, nationally and sometimes even internationally. In order to be able to compare outcomes, and then to derive broadly acceptable ‘benchmarks’, common definitions are required. Although organizations such as the American burn Association have published consensus documents about definitions for conditions such as sepsis, ventilator-associated pneumonia, wound infection, etc., considerable challenges still exist in their interpretation and application. As a result, reporting is variable and inconsistent between sites. This highlights the fact that valuable traditional research in burn care is becoming increasingly difficult to undertake without enormous resources, time and funding, while QI is increasingly being seen as a way to introduce tangible change within specific environments.

Although still a common cause of traumatic mortality globally, rates have declined significantly over the last three decades in modern burn centres [18, 25, 26]. Traditionally, mortality rates and hospital lengths of stay have been the key reported outcomes and have informed measures of excellence. But there are number of weaknesses inherent in utilizing these as prominent outcome measures: mortality rates will depend on factors beyond the control of the clinicians, including patient age, comorbidities and other factors [23, 25, 26]. Length of stay, and length of stay per percentage burn, are also flawed as measures depending on the nature of rehabilitation services available, the socio-economic factors in the community served, as well as geographical considerations, the need for follow-up, and patient comorbidities. But other broadly applicable outcome measures have been elusive. Without consensus on viable measures, we will have difficulty evaluating standards of care, comparing our services, interpreting research, and undertaking meaningful audit and quality improvement. Outcomes are very challenging to measure in patients with burn injuries owing to the heterogenous nature of the population in terms of the injury and the demographics of the patients, as well as a range of interrelating psychosocial factors [27–30].

As a result, there is a greater focus on long-term outcomes such as measures of disability, distress, social reintegration and quality of life: how best to measure these outcomes are at the forefront of debate within the burn fraternity. Patient-reported outcomes are currently very much in vogue in several areas in healthcare, not least plastic and reconstructive surgery. In the context of burn care, Klassen et al., for example, have recently validated a patient-reported outcome scale with respect to scar assessment, recognizing that healthcare workers’ opinions about satisfactory outcomes are not necessarily shared by their patients [31, 32].

The National Burn Registry (NBR) collects a series of data submitted by participating burn centres for the purposes of research, and aims to promote improvements in the delivery of burncare by comparing different units, a concept referred to as benchmarking. Klein et al. [33], using data from the NBR, were able to compare outcomes with fixed accepted benchmarks in burn care at six academic burn centres. The authors evaluated the outcomes in 541 patients with major burn injuries between 2003 and 2009. The study demonstrated a 29% survival rate benefit for patients managed in these six academic burn centres compared to those patients in the NBR. Ten standard operating procedures were assessed including resuscitation strategies, blood glucose control, burn wound management, and antibiotic prophylaxis. The multi-organ failure rate in these units was as high as 27%; the authors proposed a benchmark of time to recovery of organ dysfunction as an excellent marker for good clinical care in the management of major burns.

Falder et al.’s seven core domains of assessment after burn injury

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree