Immediate Two-Stage Breast Reconstruction Using Semilunar Expander and Purse-String Closure

Gino Rigotti

Alessandra Marchi

Immediate breast reconstruction, when possible, must be considered a better option than delayed because it requires one less surgical step and, of course, one less general anesthesia. For this reason, it is less expensive and can provide a better aesthetic outcome than if a mastectomy technique that preserves uninvolved breast skin is used.

The most popular technique is actually the “skin-sparing mastectomy” suggested by Toth and Lappert in 1991, which reduces visible scars, preserves the inframammary fold, and facilitates positioning and shaping of the new breast. Moreover, it must be considered an oncologic correct technique because many reports affirm that the skin-sparing mastectomy does not confer any additional risk of recurrence in early (T1 or T2) breast cancer.

The only concerns are (a) border line T2, T3, and over cancer; and (b) the necessity to perform breast reconstruction only by transverse rectus abdominus myocutaneous (TRAM) or latissimus dorsi myocutaneous (LD) flap (with or without implant). In the skin-sparing mastectomy, the two-stage expander/implant reconstruction is not considered.

To extend the advantages of the skin sparing, even in T3 and over tumors, and to simplify the reconstructive technique by avoiding distant flaps and using a two-stage expander/implant breast reconstruction, a modified technique is suggested. Based on a mastectomy method that originated from the skin-sparing procedure but that maintains Auchincloss and Madden oncologic theories, an immediate expander/prosthesis breast reconstruction using different patterns of skin incisions, a semilunar expander, and a purse-string closure technique is reported (Baker, 1992).

According to these concepts, it is possible to perform immediate breast reconstructions that leave hidden scars camouflaged by reconstructing the nipple-areola complex and, above all, that are oncologically safe in every T stage. Moreover, this technique does not require complex reconstructions, such as TRAM or LD flap (Bensimon and Bergmeyer, 1995), which although aesthetically satisfying, may in some instances compromise the functionality and leave unaesthetic sequel in the donor area.

Oncologic Considerations and Patient Selection

We must understand how conservative the excision could be without encountering an unacceptable increase in local recurrences. We can now define more precisely the indications of this technique of mastectomy in immediate reconstruction. The aim of this technique that spares as much skin as possible is the possibility of obtaining a morphologically correct mammary reconstruction that is not disfigured by scars. However, it respects the oncologic rules by Madden, widely accepted in more advanced cancers, that means mastectomy must be performed in a single block with the skin overlying the lump and the axilla dissection.

In our opinion, this method should be used for multicentric in situ, borderline T2, T3, and over cancers, where a modified radical mastectomy according to Madden is indicated. It can also be used in all cases where a precise staging of the cancer cannot be stated. In fact, it presents the advantages of the classical skin-sparing technique, in terms of quality of reconstructive results, while avoiding a reintervention if the cancer was found in more advanced stages than expected.

The traditional skin-sparing mastectomy achieves good results because it performs only a circular incision leaving a periareolar scar. In the technique that we suggest, this incision is possible only in the event of a central location of the cancer. We have therefore adopted the following criteria, by which patients are divided into two groups:

Patients with a central infiltrating cancer T2 borderline, T3, and over, and patients with multicentric ductal carcinoma in situ cancer—In these cases, a mastectomy with a circular incision that includes the nipple-areola complex is performed. In the event of a paracentral location, in order to include the skin over the lump, the circular incision may be extended to a maximum diameter of 10 cm. This extension is obviously related to the breast volume; in fact, it is possible only in large breasts.

Patients with peripheral T2 border line, T3, and over—In these cases, the circular incision cannot be performed because it would not be included in the same surgical block as the skin over the lump. The circular incision, including the areola and nipple, is extended in a drop shape in the peripheral direction toward the lump position. In this way, the skin overlying the lump is included in the mastectomy, sparing the quadrants not involved by the cancer.

Surgical Technique

Stage One: Mastectomy and Expander Placement

The goal of a correct mastectomy is to maximize radicality of gland removal, attempting to minimize the scars to facilitate breast reconstruction. In the first group with central, paracentral infiltrating, or multifocal intraductal comedo carcinoma, a circular incision (Fig. 38.1) is made at a distance of 1.5 cm from

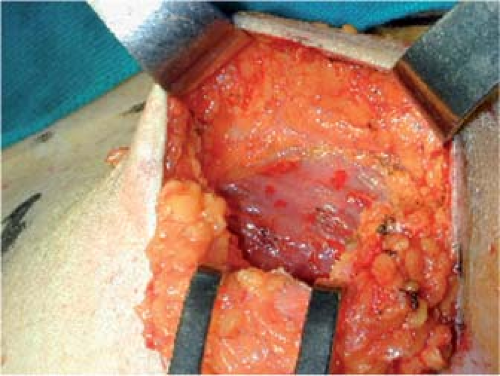

the areola edge to a maximum diameter of 10 cm. The width of the excision is determined by the position of the lump. The inframammary crease is delineated before the operation, with the patient in the upright position. Dissecting first the subcutaneous layer, and then extending in the deep layer comprehending the pectoralis fascia, mastectomy is performed (Figs. 38.2 to 38.8).

the areola edge to a maximum diameter of 10 cm. The width of the excision is determined by the position of the lump. The inframammary crease is delineated before the operation, with the patient in the upright position. Dissecting first the subcutaneous layer, and then extending in the deep layer comprehending the pectoralis fascia, mastectomy is performed (Figs. 38.2 to 38.8).

Figure 38.4. The correct plane is along the subcutaneous superficial fascia and dissects the Cooper’s ligaments. |

Electrical cautery can be used for flap elevation. In every direction, the dissection follows the superficial layer of the fascia. Superiorly, the gland falls away from the skin near the clavicle, so we do not need to extend the excision too much. Medially, the dissection ends at the lateral border of the sternum and laterally over the pectoralis major muscle toward the umerus, removing the axillary tail. Inferiorly, it is important to preserve the submammary fold; the right dissection follows the superficial

layer of the fascia to its junction with the deep layer. The skin is adherent to the chest wall at this juncture, and it corresponds to the submammary crease. Axillary dissection is carried out through the same incision; this approach proved to be large enough to perform the surgical procedure properly. Axillary dissection is not performed in intraductal multicentric comedo carcinoma. In this first group of patients, this surgical technique can be defined as “circular radical modified mastectomy” (Fig. 38.8).

layer of the fascia to its junction with the deep layer. The skin is adherent to the chest wall at this juncture, and it corresponds to the submammary crease. Axillary dissection is carried out through the same incision; this approach proved to be large enough to perform the surgical procedure properly. Axillary dissection is not performed in intraductal multicentric comedo carcinoma. In this first group of patients, this surgical technique can be defined as “circular radical modified mastectomy” (Fig. 38.8).

Figure 38.6. Dissecting the lower pole, great care must be taken in preserving the inframammary fold. |

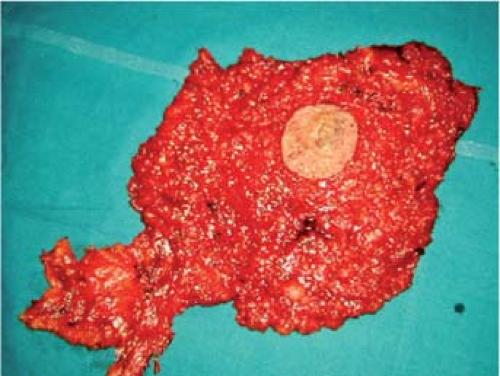

Figure 38.7. The resected specimen including gland, nipple-areola complex, and nodes dissection in continuity. |

Figure 38.8. The final result of the reconstruction (A) with the new nipple-areola complex situated symmetrically to the contralateral to cover the mastectomy scar (B). |

Figure 38.9. The teardrop mastectomy marking surrounding the areola and extending toward the peripheral quadrant where the lump is located. |

In the second group, we made the following considerations: the classic skin-sparing mastectomy technique removes the nipple-areola complex, and separately, the skin over the lump. It has, in our opinion, the disadvantage of an additional scar, which can deform the reconstructed breast, particularly if it is placed in visible areas. It also does not follow the Madden principles. Therefore, we perform a teardrop single incision circumscribing the areola at a distance of 1.5 cm and extending toward the peripheral quadrant where the lump is located (Fig. 38.9).

Figure 38.10. The scar is shorter (A) and less visible because its medial third is covered by the areola (B). |

Doing so, the incision includes the skin over the lump. This guarantees the oncologic correctness, a favorable scar that rays out from the center, and less skin to be removed from uninvolved quadrants if compared with modified radical mastectomy. Mastectomy and axillary dissection are performed in the same way as with the circular incisions. In this group, the surgical technique can be defined as “teardrop radical modified mastectomy” (Fig. 38.10). Immediate breast reconstruction is performed with expanders in all cases, with the exception of patients with extended cancer or undergoing radiotherapy.

In addition to this idea of mastectomy, a new concept began to emerge in plastic surgery in 1997—the closure of skin defects using the purse-string technique. This surgical procedure makes it possible to close circular wounds by a continuous intradermal suture, which is then tightened to fashion a purse string. In breast reconstruction, we extended this closure technique in skin excision to a diameter of 10 cm. Of course, this causes furrows that extend outward like sun rays from the wound; we noticed, however, that these furrows disappear during expansion (Fig. 38.11).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree