6 Iatrogenic disorders following breast surgery

Injection materials

Paraffin (1899–1914)

Paraffin injections1,2 were used extensively for breast augmentation from 1900 to 1914. Paraffin is a group of hydrocarbons, which is saturated with carbon to hydrogen bonds, making them relatively inert. The basic repeating unit in the polymers is: –(CH2) n– . Paraffin exists as a hard form (wax) and a soft form (Vaseline). Paraffin was usually liquefied in a warming chamber prior to injection. The first published report of paraffin injections into a patient dates back to a report by Gersuny, of Vienna, in 1899. A young man had undergone a bilateral orchidectomy for tuberculous disease. Gersuny injected paraffin into his scrotum, so that the patient could pass the physical examination necessary to join the army. Paraffin injections were subsequently used extensively for breast augmentation in Europe, the Far East and North America, until about 1914, when its complications became known. However, in the Far East, the practice was continued into the 1950s and 1960s.

Figure 6.1 shows the clinical status of a woman who received paraffin injections in the Far East 40 years earlier. She had undergone multiple debridement procedures and bilateral mastectomies over the years to treat multiple ulcers, infections and fistulae. She continued to suffer from these problems.

Liquid silicone injections (1944–1991)

Figure 6.2 shows the clinical status of a woman who received silicone breast injections in San Francisco in 1972. Over the next 30 years, much of the silicone has migrated to her abdomen. Her breasts show chronic inflammation from silicone granulomas that have infiltrated the overlying skin. Mammography of breasts injected with silicone usually demonstrates multiple cystic masses, ranging from 0.2 cm to 2.0 cm in diameter, often with calcification (Fig. 6.3). This can interfere with clinical and radiological breast evaluation.

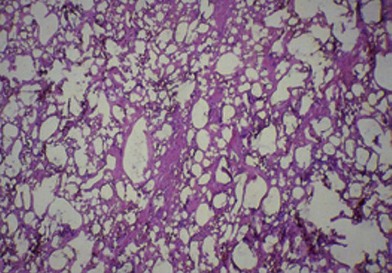

Figure 6.4 shows the microscopic appearance of a silicone granuloma, which has been excised from silicone-injected breast tissue. This shows extensive destruction of the breast parenchyma. Silicone appears as empty spaces or vacuoles, where it has been washed out during tissue preparation. Histology also shows occasional giant cells, vascular obliteration, a chronic inflammatory response and destruction of the breast parenchyma.

The second type of patient presents with skin inflammation and impending breakdown (see Fig. 6.2). As the silicone invades the dermis and epidermis of the overlying skin, the breast may show varying stages of skin circulatory difficulties, from fine telangiectasia to necrosis. Skin capillary filling time is increased. Migration of the silicone is common.

Polyacrylamide hydrogel (1988–2010)

During the past 20 years, a newer class of injectable material has been used, mainly in Ukraine, Russia, and China: polyacrylamide hydrogel (PAH).3 It is an extensively cross-linked polymeric soft tissue filler substance that has been used extensively for breast augmentation. Initially, PAH appeared to be an ideal soft tissue filler material. However, several reports have subsequently appeared, demonstrating that numerous complications can occur after PAH injections. These can develop from several months to three years after injection. They include: migration, breast lumps, pain, infection, firmness and disfigurement. The use of PAH has now been banned in China and many other countries.

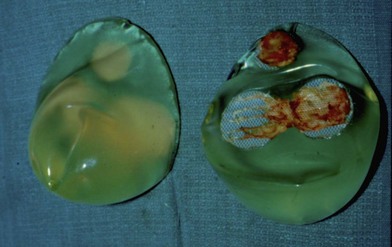

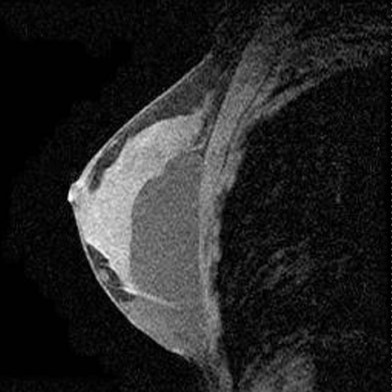

Figure 6.5 shows a 29-year-old woman who received PAH injections into both breasts in a plastic surgery clinic in Iran 1-year previously. Over the following year, she developed visible and palpable tender masses. A T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging study of the left breast shows low signal intensity material, mostly superficial to the pectoral muscles, in the subglandular plane (Fig. 6.6). The PAH was easily removed through bilateral inframammary incisions. It had the consistency of “cream of wheat” (Fig. 6.7). The patient underwent an uneventful subglandular breast augmentation with cohesive gel implants 2 years later.

Fig. 6.6 A T1-weighted image of the left breast (Fig. 6.3) showed low signal intensity material, mostly superficial to the pectoral muscles, in the subglandular plane.

This particular patient, who was injected with PAH in Iran, showed only minimal complications with migration and surface lumps in her breasts. However, we have seen other patients (e.g., from Russia), who have presented with major recurrent infections and multiple sinuses, and fistulae, many years after receiving PAH injections (Fig. 6.8). There may be different chemical formulations and different purifications of PAH in certain areas of the world.

Breast implants

The sponges (1951–1962, the early years)

The initial breast implants were developed in 1951. This introduced a totally new concept. Solid devices were now inserted behind the breast tissue to augment the size and shape of the breast. Breast implants have evolved over the past 60 years. Ivalon (polyvinyl alcohol) (Beverly Hills Surgical Supply Company) sponge was the first significant implantation material used for breast augmentation. The original sponges were manufactured by Clay-Adams Company (USA) and the Poly-Plastic Company (USA). Pangman and Wallace4 published the first study on these implants in 1955. They surmised that the outer surface of these sponges could become infiltrated with vascularized tissue, to produce a “living sponge”. Subsequent investigations showed that this process did not occur. Although the initial results were encouraging, within 1 year of augmentation, breasts became very firm and lost over 25% of their volume. Pangman introduced many modifications of his implant, including: a double-layered construction and wrapping the implant in a polyethylene sac. In spite of these modifications, all of these patients developed major firmness and shrinkage of their implants.

Figure 6.9 shows the breast appearance 19 years after augmentation with Ivalon double-layered sponge implants (circa 1958).5 This patient presented with bilateral very painful capsular contractures. She was subsequently treated by explantation and capsulectomy.

From 1952 to 1962, other sponges were also used for breast augmentation. These included: polyethylene sponge, Etheron (a polyether sponge), and Polystan (fabric tapes that were cut by machine and then wound by hand into a ball). Another type of implant that was used from 1958 to 1962 consisted of shredded polyethylene strips, each about 2 mm wide, enclosed in a casing.6

Silicone gel implants

Silicone gel breast implants were originally implanted in small numbers, and these numbers slowly increased.7 From 1962 to 1970, only about 50 000 women received gel implants in the United States. Subsequently, this number rose annually. In 1982, about 100 000 women received silicone gel implants. From 1983 to 1991, this number remained constant at 120 000–130 000 per year. Estimates indicate that, by 1992, over 2 million women had received breast implants globally, and that over 95% were silicone gel implants. Over half of these implants were inserted in North America.

Implant disruption: silicone gel implants

Most of the implant disruption studies6–9 were done in the 1990s. Before 1993, the incidence of implant disruption was thought to be very low. In January 1992, Dr David Kessler, the then Commissioner of the FDA, called for a moratorium on the use of silicone gel breast implants. Following this, hundreds of thousands of women with gel implants rushed to have their implants removed. They perceived that there was an association between their implants and medical disease. Why else would they have been banned? This huge number of women with gel implants provided very large numbers of implants for disruption assessment.

From 1963 to 1992, there have been three generations of gel implants, and a number of other lesser variations. First generation implants (1963–1972) had a thick gel and thick wall. They have generally remained intact over the years. Most first generation implants were “tear-drop shaped”. They had woven Dacron (DuPont Co, DE) patches on their posterior surfaces (Fig. 6.10) to anchor them to the chest wall in an attempt to restrict ptosis. These patches adhered very tenaciously to adjacent tissues. Subsequently, when capsular contracture developed, these patches could cause major breast distortion. In addition, significant torsion could be placed at the site of this patch. This could lead to exposure with subsequent extrusion of the implant (Fig. 6.11).

Second generation implants (1973 to the mid-1980s) had a thin gel and thin wall. Studies have shown that these implants were much more prone to disruption than first generation implants. In addition, the watery nature of the second generation implants (Fig. 6.12) could result in gel migration, which had not been seen with first generation implants. Manufacturers ultimately addressed the implant disruption problem by developing the third generation implant. Third generation implants (mid-1980s to 1992) had a stronger and thicker shell and a much more cohesive gel (Fig. 6.13)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree