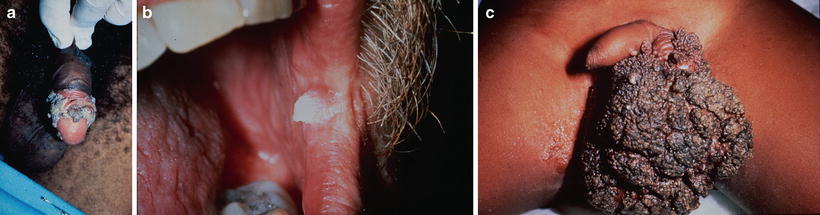

Fig. 4.1

Herpes simplex. (a) Grouped vesicles on an erythematous base on the penile shaft, (b) large chronic ulcer on the lower lip, (c) chronic perianal ulcers

HSV is treated with a thymidine kinase inhibitor such as acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir. Primary infection is treated for 10 days with acyclovir 400 mg three times daily or valacyclovir 1 g twice daily; recurrences are treated with acyclovir 400 mg three times daily for 5 days or valacyclovir 500 mg twice daily for 3 days. Suppressive therapy, with valacyclovir 500 mg to 1 g daily or acyclovir 400 mg twice daily, may be indicated based on severity of disease or frequency of recurrences. Foscarnet, cidofovir, or topical trifluridine should be considered for acyclovir-resistant strains [2].

Varicella Zoster Virus

Varicella zoster virus (VZV) is common in HIV-infected patients, with increased frequency of eruptions as CD4 cell counts decrease. In the HIV-infected patient, the zoster eruption can present in the classic dermatomal distribution (Fig. 4.2), or it may be chronic, disseminated, ecthymatous, or verrucous. These severe and atypical presentations make diagnosis difficult in some cases. As in HSV, direct fluorescent antibody, viral culture, PCR, Tzanck smear, or biopsy is useful to confirm the diagnosis. Treatment is similar to HSV infections, though higher doses of medications are administered. Intravenous antiviral therapy is indicated in disseminated zoster or zoster ophthalmicus. VZV vaccine may be indicated in early-stage HIV infected adults to prevent the eruption or the ensuing postherpetic neuralgia but is not universally recommended [2].

Fig. 4.2

Herpes zoster eruption in dermatomal distribution on the arm. Courtesy Dr. Ncoza Dlova

Oral Hairy Leukoplakia

Oral hairy leukoplakia is caused by Epstein-Barr virus and is indicative of advancing immunosuppression, developing in up to 25 % of HIV infected patients. Lesions appear as adherent, corrugated white plaques with hair-like projections on the lateral tongue (Fig. 4.3). The condition is not associated with progression to malignancy. Lesions tend to regress with HAART and immune reconstitution. Treatments such as local destruction with cryotherapy, topical podophyllin or tretinoin gel, or oral antivirals such as acyclovir may be considered but are often not necessary as the condition is usually asymptomatic [2].

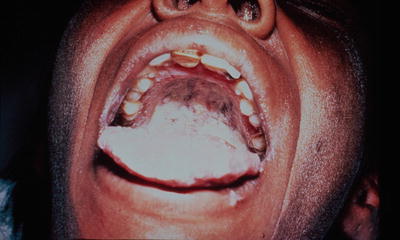

Fig. 4.3

Oral hairy leukoplakia on the lateral tongue

Human Papillomavirus

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is very common in HIV-positive patients, and lesions may be larger and more resistant to treatment than in immunocompetent patients. HPV is implicated in common warts, an acquired epidermodysplasia verruciformis-like syndrome, and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin. Anogenital manifestations of HPV infection include condylomata acuminata, Buschke–Lowenstein tumor (giant condyloma), Bowen disease, and intraepithelial neoplasia or invasive carcinoma of the anus, penis, vulva, or cervix (Fig. 4.4a–c). Widespread use of HAART has not decreased prevalence of genital HPV infection and has paradoxically led to an increase in cervical, anal, and vulvar malignancies because of extended life expectancy in the HIV infected population [12]. Cervical and anal Papanicolaou smear screening is advised every 6–12 months in HIV infected patients, and HPV vaccines may offer protection against reinfection or reactivation in previously exposed patients [2].

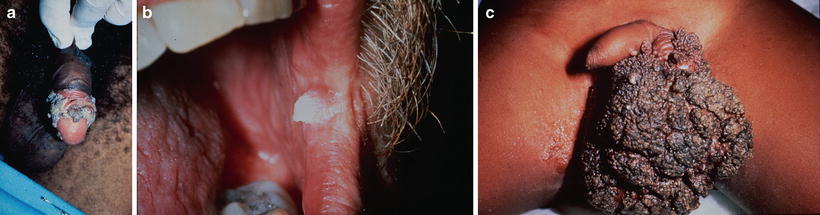

Fig. 4.4

Human papillomavirus. (a) Condylomata on the penis, (b) oral condyloma, (c) Buschke–Lowenstein tumor

Treatment of HPV-associated condyloma is often less effective in HIV-infected patients and dependent on immune status. Surgical options include cryotherapy, usually repeated every 4–6 weeks, or excision for larger lesions. Intralesional 5-fluorouracil and interferon alpha may also be effective. Topical therapies applied by the patient include imiquimod, three times per week, or podophyllotoxin gel, 3 days on and 4 days off; in-office topical therapies applied by the clinician include podophyllotoxin solution or trichloroacetic acid.

Molluscum Contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum lesions are commonly seen in patients with CD4 counts below 200/μL [13]. Typical skin-colored, dome-shaped umbilicated papules may be seen most frequently on the face, neck, groin, or intertriginous areas (Fig. 4.5a). They can progress to become large, confluent, and disfiguring (Fig. 4.5b). Lesions should be differentiated from atypical mycobacterial infections or disseminated fungal infections such as cryptococcosis, penicilliosis, or histoplamosis [2]. The diagnosis may be confirmed in office with Giemsa or toluidine blue staining of a smear of the core of the umbilicated lesions, revealing Henderson–Patterson bodies. Alternatively, a skin biopsy is diagnostic. Molluscum lesions may regress with HAART, though local destructive treatments such as cryotherapy, curettage, or electrodessication and topical therapies including imiquimod, cidofovir, cantharidin, or trichloroacetic acid are mainstays of treatment [14–16].

Fig. 4.5

Molluscum contagiosum. (a) Classic umbilicated papules on the face of a child, (b) giant molluscum lesions on the face

Staphylococcus aureus

HIV infected patients have an increased rate of Staphylococcus aureus colonization and resultant skin infections [11]. These commonly present as in the immunocompetent population with furuncles or carbuncles that can progress to cellulitis and abscesses (Fig. 4.6a, b). Other less frequent presentations include pyomyositis, with intramuscular abscesses, and botryomycosis, a chronic suppurative granulomatous infection with fistulae draining sulfur granules and purulent material [2]. Treatment of any abscess should include drainage. Antibiotic therapy is culture driven; oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline, or clindamycin often have activity against methicillin-resistant strains and intravenous vancomycin is indicated for more severe infections. Eradication of colonization with intranasal mupirocin and bleach baths or chlorhexidine skin cleansers may also be helpful as a preventative measure.

Fig. 4.6

Staphylococcus aureus. (a) Staphylococcal pyoderma, (b) multiple abscesses on the scalp

Syphilis

HIV positive patients who have a history of multiple sexual partners and other sexually transmitted diseases have an increased risk of coinfection with syphilis, caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. Secondary syphilis may present with the classic papulosquamous eruption, but other atypical features may be seen in the setting of HIV coinfection such as nodulo-ulcerative lesions or palmoplantar keratoderma of syphilis [11]. HIV infection is associated with false-negative results in nontreponemal and treponemal tests such as the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption (FTA-ABS) respectively. Furthermore, very high titers of RPR may have false-negative results that become positive with serum dilution, known as the prozone phenomenon [17]. Syphilis is treated with intramuscular benzathine penicillin, dose dependant on the stage of infection. It is controversial whether HIV patients experience an increased rate of treatment failure with standard therapy regimens or more rapid progression to secondary and tertiary syphilis [17, 18]. Lumbar puncture is indicated in any HIV positive patient with syphilis and neurologic symptoms to rule out neurosyphilis.

Bacillary Angiomatosis

Bacillary angiomatosis, due to Bartonella henselae or quintana, presents with red to violaceous papules and nodules that may resemble Kaposi sarcoma or pyogenic granuloma (Fig. 4.7). It was first described in HIV positive patients and is associated with CD4 counts lower than 100. Diagnosis may be confirmed by biopsy of skin lesions as well as bacterial culture or PCR of tissue or blood. Up to 50 % of patients with skin lesions have involvement of internal organs, often the liver and spleen [19]. Treatment is with prolonged courses of macrolides or tetracyclines for a minimum of 2 months’ duration. Use of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for Pneumocystis prophylaxis may suppress Bartonella and decrease the incidence of bacillary angiomatosis [2].

Fig. 4.7

Bacillary angiomatosis

Candidiasis

A common initial presentation of HIV infection is oral candidiasis or thrush, with white exudate on the tongue, palate, or buccal mucosa (Fig. 4.8). Other manifestations of Candida infections include angular cheilitis, vaginal candidiasis, chronic paronychia, or intertrigo. More severe disease is correlated with lower CD4 counts, and oropharyngeal chronic infection is a reservoir for disseminated disease and candidemia in severely immunosuppressed patients. Diagnosis may be confirmed by fungal culture or potassium hydroxide preparations of scrapings from mucous membranes. Oral candidiasis may be treated with topical nystatin “swish and swallow” preparations or clotrimazole troches. Oral fluconazole, 100 mg daily, or itraconazole, 100 mg twice daily, is indicated for chronic or recurrent disease, but prolonged use can promote resistance [2]. Amphotericin, caspofungin, or voriconazole may be required for resistant organisms or disseminated infection. Prophylaxis with fluconazole, 100–200 mg weekly, may be considered in patients with severely depressed CD4 counts.

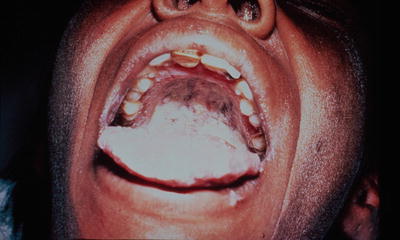

Fig. 4.8

Oral candidiasis

Scabies

Scabies, caused by Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis, is the most common ectoparasitic skin infection in HIV positive patients [8]. Presentation in immunocompetent patients is similar to that of the general population, with burrows seen in interdigital web spaces, flexor aspects of the wrists, genital, periumbilical, and intertriginous areas. With more advanced HIV infection, scabies infestation may involve greater surface area of the body, including the ears, face, and scalp, or present in crusted or exaggerated papular forms with or without typical burrows (Fig. 4.9). Crusted, fissured plaques may become superinfected, in some cases leading to bacteremia. HIV-infected patients tend to have higher mite burden than immunocompetent hosts. Diagnosis is confirmed by examining scrapings of suspicious skin lesions in mineral oil for mites, ova or feces. Scabies infestation is treated with topical permethrin 5 % cream, which may require repeated applications, or oral ivermectin 200 μg/kg administered in two doses 2 weeks apart [2]. Keratolytics such as topical salicylic acid should be considered in patients with thick crust and scale to allow penetration of topical medications. Close household contacts should be treated in confirmed cases.

Fig. 4.9

Plaque of crusted scabies in the umbilical region

Non-infectious HIV-Related Cutaneous Disorders

Seborrheic Dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis is the most common cutaneous manifestation of HIV, affecting up to 85 % of patients [20]. It may be seen in all stages of disease but becomes more severe, diffuse, and resistant to therapy with more advanced immunosuppression [21]. HIV-infected patients often exhibit the typical presentation of pink plaques with greasy yellow scale on the scalp, face, and central chest (Fig. 4.10). With more advanced HIV infection, patients may present with involvement of the entire face and chest or even total body erythroderma. An abrupt onset of seborrheic dermatitis or a severe worsening of a preexisting case should prompt HIV testing.

Fig. 4.10

Scaling plaques on the scalp, face, and chest in a patient with seborrheic dermatitis

Seborrheic dermatitis has been linked to Malassezia yeast, although studies investigating the amount or species of these commensal organisms have failed to demonstrate consistent differences between patients with seborrheic dermatitis and normal controls [22]. The disease responds to antifungal medications such as topical ketoconazole cream or shampoo, terbinafine cream or zinc pyrithione shampoo. Other topical treatments include selenium sulfide and sulfur or tar shampoos, low potency topical corticosteroids, or metronidazole gel. In more severe cases, oral antifungals may be considered as an adjunct to topical preparations; options include ketoconazole 200 mg daily for 4 weeks, itraconazole 200 mg daily for 7 days, or terbinafine 250 mg daily for 4 weeks [22].

Psoriasis in HIV

Psoriasis prevalence in HIV patients is slightly higher than that of the normal population, affecting approximately 2–5 % of HIV infected patients [8, 23]. Clinical manifestations in HIV patients are similar to non-infected individuals, including classic chronic plaque psoriasis (Fig. 4.11a, b), though some HIV patients are more prone to developing palmoplantar psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Other possible presentations include guttate psoriasis, often developing after streptococcal or staphylococcal infections; sebopsoriasis, with clinical features of both seborrheic dermatitis and psoriasis; or total body involvement (erythroderma) that may become secondarily infected. The severity of psoriasis worsens in advanced AIDS and a preexisting psoriasis is usually exacerbated with HIV infection [23]. As in seborrheic dermatitis, an acute worsening or abrupt onset of psoriasis should prompt the consideration of HIV screening.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access