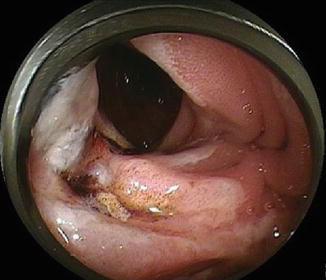

Fig. 12.1

Leak from gastric pouch

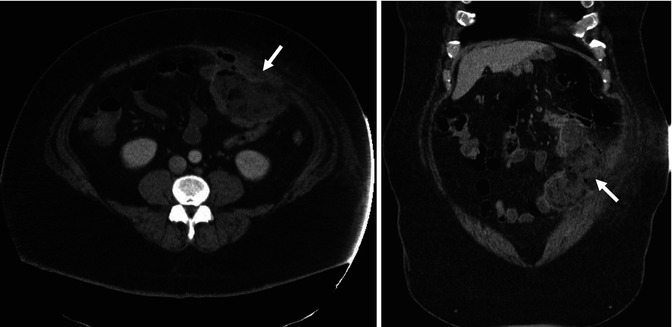

Fig. 12.2

Abscess (arrow) formation due to leak from jejunojejunal anastomosis

The surgical principles for treating a leak include broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage, identification and repair of the defect, irrigation and control of the contaminated area, and making access for feeding (jejunostomy or gastrostomy tube). With leaks at the gastrojejunal anastomosis, if the condition of the tissues is not bad, the defect may be closed with primary suturing, followed by irrigation of the area and the placement of drains. When primary closure of the defect is not possible, wide drainage is an option.

Jejunojejunostomy leaks are a serious complication, with a higher mortality rate compared to other leaks of up to 40 %. Surgical intervention must be promptly performed due to the presence of hemodynamic instability or rapid clinical deterioration. In general, these anastomotic defects can be more easily detected and repaired than those of the gastrojejunostomy. It is recommended that decompression of the excluded stomach using tubing gastrostomy in patients with complicated conditions.

Surgical therapies for persistent leaks are technically difficult and often unsuccessful. New approaches using endoscopic repair techniques include the use of fibrin glue and/or placement of covered stents and have been shown to be safe and effective in some patients.

12.7.1.2 Acute Gastric Remnant Dilatation

Gastric remnant dilatation is a rare (0.6 %) but potentially lethal complication following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. The gastric remnant is a blind pouch and may become distended due to the closed-loop obstruction that can develop following obstruction of the biliopancreatic limb or paralytic ileus. Progressive distension can ultimately lead to a blowout of the staple line, spillage of massive gastric contents, and subsequent severe peritonitis.

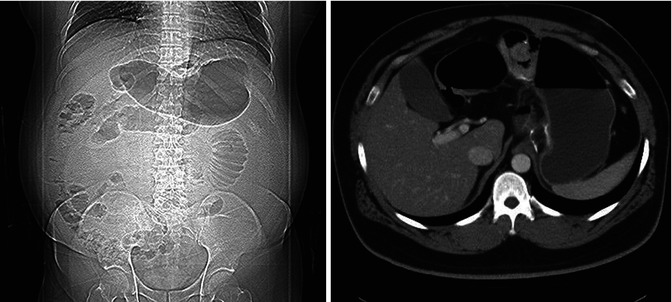

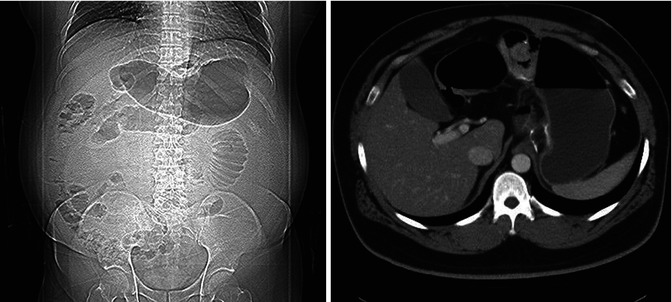

The clinical features of this complication include severe epigastric pain, hiccups, left upper quadrant tympany, shoulder pain, abdominal distension, tachycardia, or shortness of breath. Radiographic assessment may demonstrate a large gastric bubble on a plain abdominal x-ray or CT scan (Fig. 12.3). The treatment of this consists of percutaneous gastrostomy or emergency surgical decomtpression with a gastrostomy. Immediate surgical exploration and decompression are required if percutaneous drainage is not feasible or if a perforation is suspected. It also requires the appropriate management of the underlying biliary limb obstruction.

Fig. 12.3

Acute gastric dilatation

12.7.1.3 Stomal Stenosis

Stomal (anastomotic) stenosis has been described in 6–20 % of patients who have undergone RYGB. The etiology is uncertain, although tissue ischemia or increased tension on the gastrojejunal anastomosis is believed to have a role. The stomal stenosis rate is higher in LRYGB and may be related to the use of the small-diameter circular staplers, which are commonly used by many surgeons.

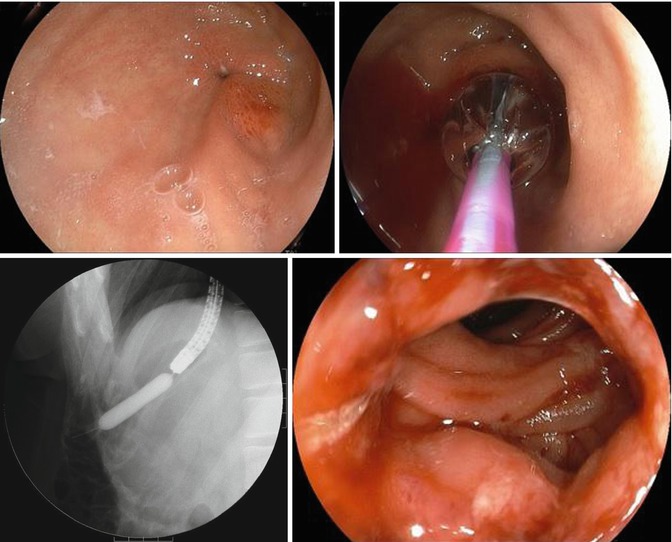

Patients typically present several weeks after surgery with nausea, vomiting, dysphagia, gastroesophageal reflux, and eventually an inability to tolerate the oral intake of foods or liquids. The diagnosis is usually established by endoscopy or with an upper gastrointestinal series. Endoscopic balloon dilation is usually successful (Fig. 12.4). Repeat dilation sessions may be required for some patients. Surgical revision is reserved for those who have persistent stenosis despite repeated dilations.

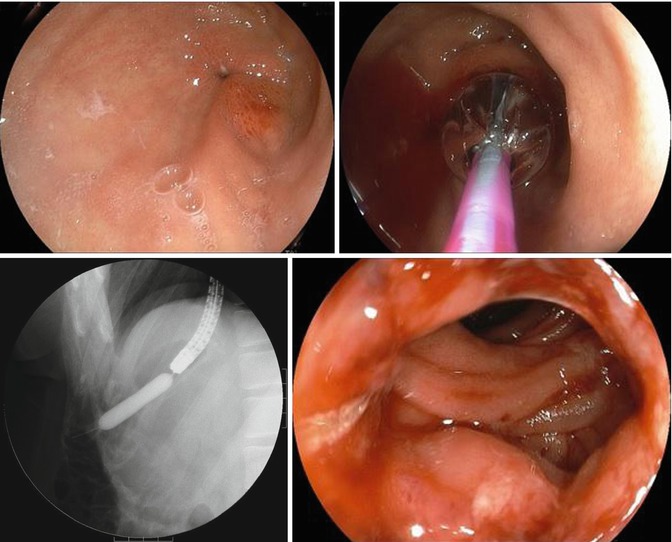

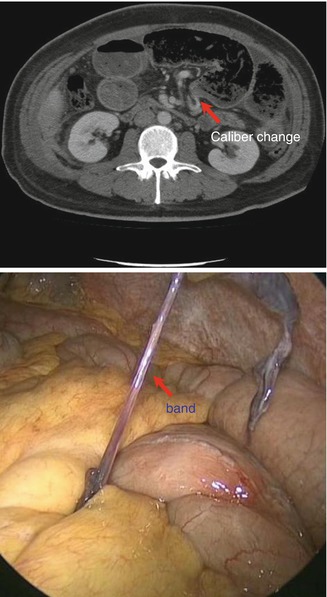

Fig. 12.4

Endoscopic balloon dilation for stomal stenosis

12.7.1.4 Marginal Ulcers

Marginal ulcers have been reported in up to 16 % of patients after RYGB. Ulcers can occur from several weeks to many years after surgery. Marginal ulcers occur near the gastrojejunostomy and result from acid injuring the jejunum, or they can be associated with a gastrogastric fistula. The risk factors for marginal ulcers include a large proximal gastric pouch; poor tissue perfusion due to tension or ischemia at the anastomosis; the presence of foreign material, such as staples or nonabsorbable sutures; excess acid exposure in the gastric pouch due to gastrogastric fistulas; the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); Helicobacter pylori infection; or smoking.

Patients with marginal ulcers present with nausea, heartburn, epigastric pain, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, and/or perforation (Figs. 12.5 and 12.6). The diagnosis of a marginal ulcer is established by upper endoscopy (Fig. 12.7). The majority of patients (95 %) can be successfully treated by medical treatment consisting of gastric acid suppression, such as using proton pump inhibitors. In addition, NSAIDS should be discontinued, and patients should be encouraged to stop smoking.

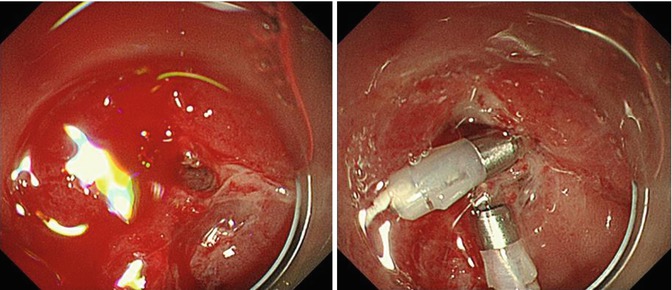

Fig. 12.5

Acute bleeding from marginal ulcer

Fig. 12.6

Acute perforation

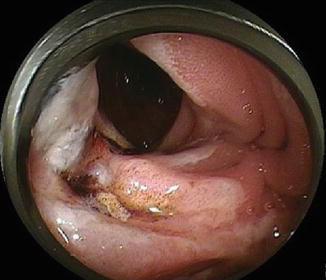

Fig. 12.7

Marginal ulcer

After maximal medical management fails, if persistent symptoms and signs of ulcers are present, this is an indication that surgery is necessary and can include resection of the anastomosis and making a smaller gastric pouch. Perforated ulcers with generalized peritonitis and upper GI bleeding that cannot be controlled by endoscopic therapy also need emergency surgery.

12.7.1.5 Gastrogastric Fistulas

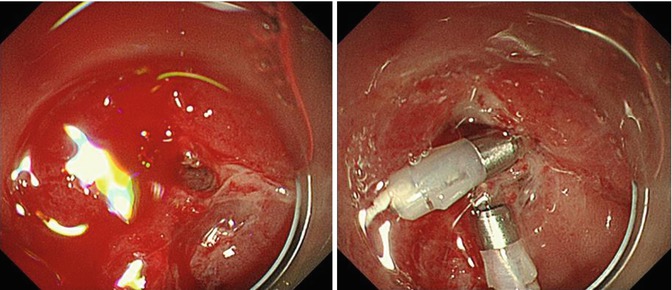

A gastrogastric fistula (GGF) results from a recanalization between the gastric pouch and excluded distal gastric remnant, despite the fact that the stomach has been divided using stapler devices. The incidence of the complication varies in literature from 2 to 25 %. GGF does not require urgent intervention, but it can lead to three major long-term problems: recurrent stomal ulcers, gastroesophageal reflux, and sudden weight regain. The presence of these complications should prompt an evaluation for GGF. They can be detected easily by an upper gastrointestinal series. Endoscopy can also detect this condition (Fig. 12.8), though small fistulas may be difficult to identify. In patients who have suboptimal weight loss or refractory ulcers, surgical re-separation of the gastric pouch and excluded stomach may be necessary. Treatment with an endoluminal technique may be possible in the future.

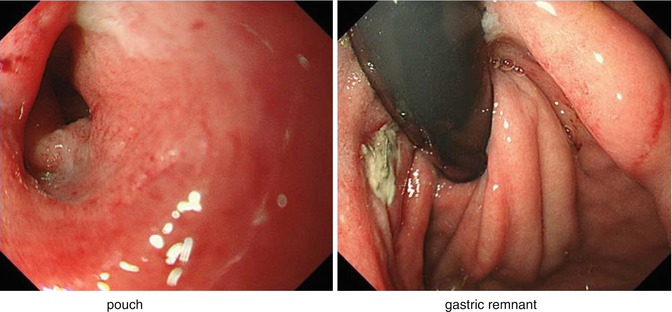

Fig. 12.8

Gastrogastric fistula

12.7.1.6 Internal Hernias and Small Bowel Obstructions

Small bowel obstruction can occur through several mechanisms, both early and late after RYGB. Adhesive bowel obstructions can occur after both open and laparoscopic approaches (Fig. 12.9). Internal hernias are the most common cause of postoperative obstruction following laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. This is because the Roux-en-Y anatomy is associated with potential internal spaces through which herniation of the small intestine can occur. Three potential areas of internal herniation are the mesenteric defect at the jejunojejunostomy, the space between the transverse mesocolon and Roux limb mesentery (Petersen’s space), and the defect in the transverse mesocolon if the Roux limb is passed retrocolically. Internal hernias have been described in 0–5 % of patients undergoing laparoscopic bariatric surgery. Hernias through the transverse mesocolon are the most common and require surgical intervention.

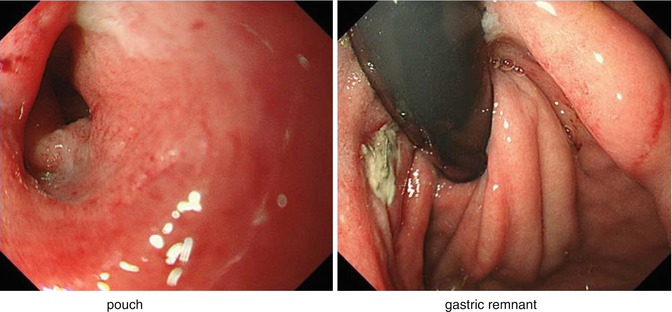

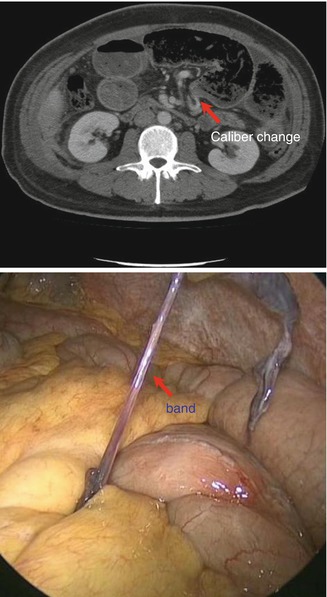

Fig. 12.9

Small bowel obstruction due to band formation

To reduce the incidence of internal hernias, all areas of potential herniation should be closed with nonabsorbable sutures. Radiological evaluations may be useful, with CT scans providing the most accurate diagnostic tool for internal hernias. The “mesenteric swirl sign,” which indicates mesenteric vascular twisting on a CT scan, is the best indicator of an internal hernia following gastric bypass (Fig. 12.10). A patient suspected to have an internal hernia as the etiology of their abdominal pain indicates urgent surgical exploration. The treatment of internal hernias can be done laparoscopically (Fig. 12.11). The exploration begins at the gastrojejunostomy, and the entire small bowel should be checked to the cecum, including the jejunojejunal anastomosis, biliopancreatic limb, and remnant stomach, with all potential mesenteric defects inspected. If an internal hernia was present, after the reduction of an internal hernia, all remaining mesenteric defects should be closed with nonabsorbable running sutures. If exploration is performed in a timely manner, the rate of bowel resection is relatively low.

Fig. 12.10

Petersen’s hernia. Mesenteric swirl sign (arrow)

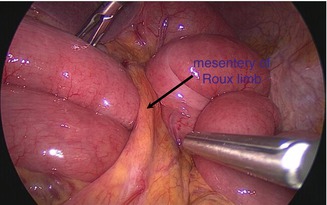

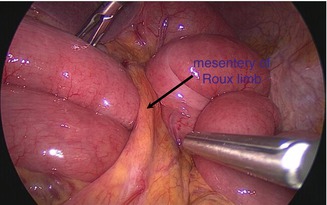

Fig. 12.11

Petersen’s hernia

However, strangulated hernias may require extensive small bowel resection and can potentially result in the development of short bowel syndrome. Therefore, if an internal hernia with bowel ischemia is suspected, then surgical exploration should be performed promptly without hesitation.

12.7.1.7 Cholelithiasis

Rapid weight loss can be a risk factor for the development of gallstones. Cholelithiasis develops in as many as 38 % of patients within 6 months of bariatric surgery, and 10–41 % of such patients become symptomatic. The high frequency of cholelithiasis can be reduced to as low as 2 % with a 6-month course of ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), given prophylactically after weight loss surgery.

The decision to perform a cholecystectomy at the time of bypass is controversial. There is no evidence that simultaneous cholecystectomy for gallstones at the time of RYGB benefits the patients. Cholecystectomy can be performed safely on those who develop cholelithiasis. However, choledocholithiasis may be more difficult to manage after performing gastric bypass surgery.

12.7.1.8 Dumping Syndrome

Dumping syndrome can occur in up to 50 % of post-gastric bypass patients when high levels of simple carbohydrates are ingested. Although sometimes considered a complication of gastric bypass, in most cases, dumping syndrome is considered to contribute to weight loss, in part by causing the patient to modify his/her eating habits. The lightheadedness, dizziness, abdominal pain, bloating, and diarrhea associated with dumping syndrome are often potent negative reinforcements promoting the loss of desire for concentrated sweets.

12.7.1.9 Postoperative Hypoglycemia

A small number of patients develop blackouts and seizures after weight loss surgery due to a severe form of recurrent hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. Pancreatic nesidioblastosis has been proposed as a mechanism for the pathological finding of beta islet hypertrophy in these patients, although a few cases of insulinomas have been found. Gastric bypass-induced weight loss may also unmask an underlying beta-cell defect or contribute to pathological islet hyperplasia.

12.7.1.10 Vitamin, Mineral, and Nutritional Deficiencies

Vitamin, mineral, and nutritional deficiencies are common in severely obese patients and can be exacerbated following bariatric surgery, making postoperative, lifelong compliance with appropriate dietary choices and vitamin supplementation imperative. After RYGB, decreased oral intake, as well as altered absorption of food from the stomach and small bowel, reduces the absorption of various micronutrients, particularly iron, calcium, vitamin B12, thiamine, and folate. Nutritional deficiencies are expected following bariatric surgery, and supplementation is the best form of prevention.