History and Physical Examination

INTRODUCTION: ORGANIZATION OF THE CLINICAL EXAMINATION

INTRODUCTION: ORGANIZATION OF THE CLINICAL EXAMINATION

The physician must first explore the patient’s presenting complaint and its history, along with his or her general and vascular history. Functional disorders and aesthetic complaints are addressed. The physical examination (including Doppler auscultation) is initially performed with the patient standing, and then in the supine and prone positions. A preliminary assessment is thus performed that includes diagnosis of the primary varicose veins and their regions of involvement. Further evaluation is required to quantify functional and aesthetic impairment, to assess the risks of possible complications, and to establish a plan for management that will be medically appropriate and acceptable to the patient.

History

As in all good medical practice, evaluation of the patient with varicosities begins with a complete history. The clinical history should include general medical and surgical information, as well as information about vascular disease. Apart from the presenting complaint, it is important to document the onset of the problem and the clinical course of the disease. Any predisposing or aggravating factors and any situations that improve the symptoms are also recorded. The patient should be explicitly asked about each of the common symptoms that are seen with venous insufficiency, including leg heaviness, exercise intolerance, pain or tenderness along the course of a vein, pruritus, “restless” legs, night cramps, edema, and paresthesias. Many of these symptoms will improve after treatment. The history form that patients complete prior to the physical examination is available in Chapter 25.

Presenting Complaint

Patients may consult the phlebologist because of symptoms or aesthetic concerns, for advice on the medical implications of varicose veins, or simply seeking to know methods of treatment. Some visits are prompted by complications such as the rupture of a varicose vein with bleeding or the recent development of dermatitis, thrombophlebitis, cellulitis, or ulceration. Treatment that does not properly address the patient’s primary concerns will not result in a satisfactory overall outcome. Both cosmetic and medical concerns need to be addressed. Patients also need to have a thorough understanding of the nature of gravitational influence and genetics on the formation of new veins.

General History

The general history information of the patient should include the following:

• Sex, age, weight, and height.

• Medical history, including hypertension, diabetes, allergy history, tobacco consumption, rheumatological history, and general disease.

• Surgical history, including any fractures or surgical operations.

• Gynecological and obstetric history, including the number of pregnancies and miscarriages; plan for future pregnancies1; duration, dosage, and effect on venous complaints of hormone replacement therapy or oral contraception; and any variation of symptoms with the menstrual cycle.

History of Vascular Disease

The history of vascular disease of a patient should include the following:

• History of venous insufficiency, including the date of onset of visible abnormal vessels and onset of any symptoms.

• Presence or absence of predisposing factors such as heredity, trauma to the legs, occupational prolonged standing, or sports participation.

• History of edema, including the date of onset, predisposing factors, site, intensity, hardness, and modification after a night’s rest.

• History of any prior evaluation of or treatment for venous disease, including medications, injections, surgery, or compression.

• History of superficial or deep thrombophlebitis, including the date of onset, site, predisposing factors, and sequelae.

• History of any other vascular disease, including peripheral arterial disease, blood clots, coronary artery disease, lymph-edema, or lymphangitis.

• Family history of vascular disease of any type.

Contraindications to sclerotherapy should be investigated thoroughly. These include hypercoaguable states (summarized in Chapter 18), inability to ambulate or comply with compression, arterial insufficiency, allergy to sclerosing solutions, pregnancy, or a significant medical issue that would interfere with healing, such as poorly controlled diabetes.

Active Symptoms

Symptoms present at the time of the visit are documented and described in terms of their site, their time of onset, character, and any factors that aggravate them or improve them. Symptoms of venous disease are most often, but not exclusively, located on the medial surface of the leg. These symptoms are often increased by heat, prolonged standing, or during the premenstrual/menstrual period in women and are typically relieved by cold, ambulation, rest with leg elevation, or wearing of gradient elastic stockings.2

Characteristics of venous pain include a dull ache, burning, or pruritus. This pain may be localized to a protruding varicose or reticular vein. It is rarely described as a sharp stabbing pain or pain radiating down the back of the thigh. Surprisingly, nighttime muscle cramping can be caused by venous insufficiency. Restless legs may rarely be caused by venous insufficiency. Symptoms are typically substantially improved after treatment.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Introduction

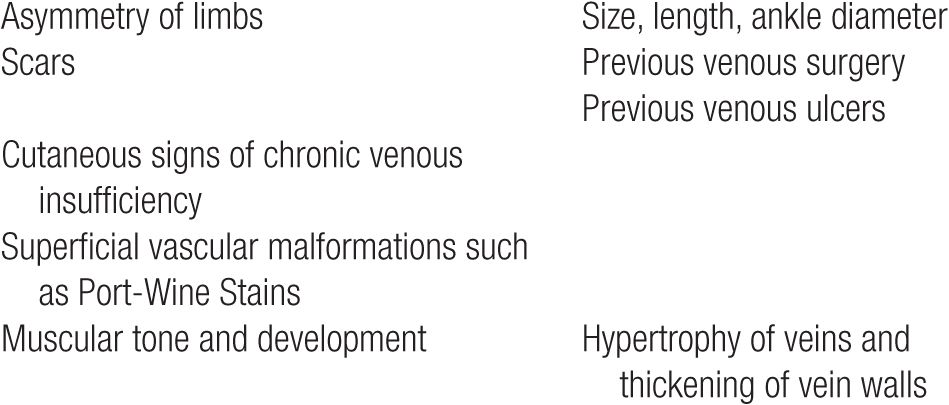

Physical examination of the lower extremities, while extremely important, is not always the most reliable guide because clinical findings common in venous disease are also common to many other entities. Findings of special importance to the phlebologist on physical examination are listed in Table 6-1. Some of these physical findings may help guide the choice of treatment modality and its degree of difficulty. For example, if a patient is a runner with muscular, well-toned legs, the veins will have a thick adventitia and may pose a greater therapeutic challenge. Ambulatory phlebectomy of such thick-walled veins is more time-consuming and tedious; this type of vein is often more resistant to sclerosing solutions.

TABLE 6-1

Physical Examination Findings Associated with Venous Reflux

Swelling may result from acute venous obstruction (such as is seen in deep vein thrombosis), from deep or superficial venous reflux, or from other nonvenous causes. Hepatic insufficiency, renal failure, cardiac decompensation, infection, trauma, and environmental effects can all produce lower-extremity pitting edema that may be indistinguishable from the edema of venous obstruction or venous insufficiency. Edema due to lymphatic system malfunction may be due to primary obstruction of lymphatic outflow or may be secondary to overproduction of lymph due to severe venous hypertension (“venolymphatic syndrome”).

Despite the increasing popularity of technical laboratory investigations, clinical evaluation of the patient with venous disease remains the basis on which the diagnostic and therapeutic approach is built. The presenting complaint and the patient’s goals for treatment must be defined and clearly understood. Knowledge of the patient’s medical, social, work, and family environment is important. A general assessment of the patient’s venous disease, including its severity and consequences, is critical to judging the risks of complications, both vascular (superficial or deep venous thrombosis) and trophic (eczema, cellulitis, and leg ulcer).

Rather than being considered a special diagnostic modality, the use of Doppler for auscultation is an integral part of the clinical examination of patients with venous disease.3 Doppler is so important to the physical examination that it may be considered the stethoscope of the phlebologist, although many would say that use of Duplex ultrasound is so convenient and available that it has replaced the Doppler. Historically, handheld Doppler would help to confirm the clinical findings of the physical examination and was particularly valuable because it could reveal clinically undetectable subsurface reflux before the age of laptop-sized Duplex ultrasound devices. Duplex ultrasound, like the Doppler it replaced, helps to define the topography of varicose disease and the hemodynamic status of the deep venous system. Repeated examinations over time can help document the results of treatment or the natural course of the disease. Handheld Dopplers were portable and relatively inexpensive but required abundant practice to become proficient in their use, while Duplex ultrasound being so visual and with such high resolution has become the gold standard of noninvasive examination of the venous system. It allows direct visualization of the veins and identification of flow through venous valves. Some phlebolgists still screen with the hand-held Doppler but depend on the Duplex ultrasound for a specific venous examination of anomalies detected on examination.

Equipment

The clinical examination requires a medical file, an examination platform, excellent lighting, a phlebological examination table, a continuous-wave Doppler apparatus, and a small amount of miscellaneous equipment. Most advanced phlebology practices will also rely on Duplex ultrasound.

Examination Platform

Having the patient stand on a platform consisting of two or three steps will greatly increase the physical comfort for the physician and allow for a more complete examination. Thus, the patient can be examined in a standing position without requiring the physician to contort his or her body in a nonergonomic manner. Platforms may include a railing to increase safety and to reduce any patient anxiety (Figure 6-1).

![]() FIGURE 6-1 Examination platform: Having the patient on either steps or a stool makes examination easier for the physician.

FIGURE 6-1 Examination platform: Having the patient on either steps or a stool makes examination easier for the physician.

Lighting

Lighting should be even and consistent. The simplest approach is to have a 75-W lamp on each side of the patient. Uniform overhead fluorescent lighting is satisfactory. Hot spots from strong halogen lamps will bleach out reticular veins and should be avoided. Magnifying lamps or magnifying glasses are sometimes helpful when small lesions are to be examined in more detail. A useful device to examine smaller telangiectasias is a cross-polarized lighting system manufactured by Syris Scientific (Gray, ME). These devices produce optimum light density for subsurface viewing approximately 1 mm below the skin’s surface. The visual enhancement of fine telangiectasia and hard-to-see reticular veins is seen in Figure 6-2. Another technique called transillumination may be helpful to map out reticular veins within 1–2 mm of the skin surface, which is detailed in Chapter 22.

![]() FIGURE 6-2 Enhancement of view of telangiectasia. A. View with normal fluorescent lighting. B. View with Syris v600 polarizing vision device.

FIGURE 6-2 Enhancement of view of telangiectasia. A. View with normal fluorescent lighting. B. View with Syris v600 polarizing vision device.

Examination Table

The examination table can be simple and inexpensive but should allow examination of the patient either in a half-seated or a totally supine position. A hydraulic examination table will facilitate the examination by permitting the patient to be raised to a level convenient for the examiner and to be tilted into Trendelenburg and reverse Trendelenburg positions as needed. A hydraulic table will also be useful for subsequent treatments.

Doppler Apparatus

The continuous-wave Doppler examination is the simplest, least expensive, and most rapid method by which to enhance the physical examination of patients with chronic venous insufficiency, provided it is performed by an experienced operator with a good knowledge of pathophysiology and all venous anatomical variants. The Doppler equipment and examination are described in detail elsewhere but may now be regarded as a technique replaced by a new technology. Manufacturers and distributors of diagnostic equipment are listed in Chapter 25. Beware that Doppler has been in large part replaced by high-resolution, highly portable Duplex ultrasound devices.

Minor Equipment

Elastic tourniquets can be useful for Trendelenburg maneuvers. A digital camera is essential to provide documentation of the current state of disease. A tape measure must be available for leg diameter measurements and a set of calipers will assist in measuring the diameter of the largest varicose veins.

Physical Examination (Standing)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree