The Spectrum of Venous Disease

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

From the burning or throbbing pain of hormonally mediated telangiectasias to the hemodynamic collapse of thromboembolism, diseases of the peripheral venous system are observed frequently in modern life. Clinicians are faced with a spectrum of venous diseases that appear in varied manifestations in patients of all ages. Although venous disease in its mildest forms is merely uncomfortable, annoying, or cosmetically disfiguring, severe venous disease can produce severe systemic consequences.

The visual appearance of the lower extremities is a useful but not always reliable guide to peripheral venous condition. Swelling, for example, may result from acute venous obstruction or from deep or superficial venous reflux, or it may be completely unrelated to the venous system. Hepatic insufficiency, renal failure, cardiac decompensation, infection, trauma, and environmental effects can all produce lower extremity edema that may be indistinguishable from the edema of venous obstruction or venous insufficiency.

The most common form of venous disease is venous insufficiency caused by valve incompetence in the deep or superficial veins. Deep venous insufficiency occurs when valves are damaged by deep vein thrombosis. Superficial venous insufficiency occurs when a high-pressure leakage develops between the deep and superficial systems or within the superficial system, followed by a sequential failure of the venous valves in superficial veins. Venous insufficiency syndromes allow venous blood to escape from its normal flow path and to flow in a retrograde direction or reflux down into an already-congested leg. Over time, incompetent superficial veins acquire the typical dilated and tortuous appearance of varicosities.

The presence and size of visible varicosities is not a reliable indicator of the volume or pressure of venous reflux, because a vein that is confined within fascial planes or is buried beneath subcutaneous tissue can carry massive amounts of high-pressure reflux without being visible at all. Conversely, even a small increase in pressure can eventually produce massive dilatation of an otherwise normal superficial vein that carries very little flow.

CEAP CLASSIFICATION

CEAP CLASSIFICATION

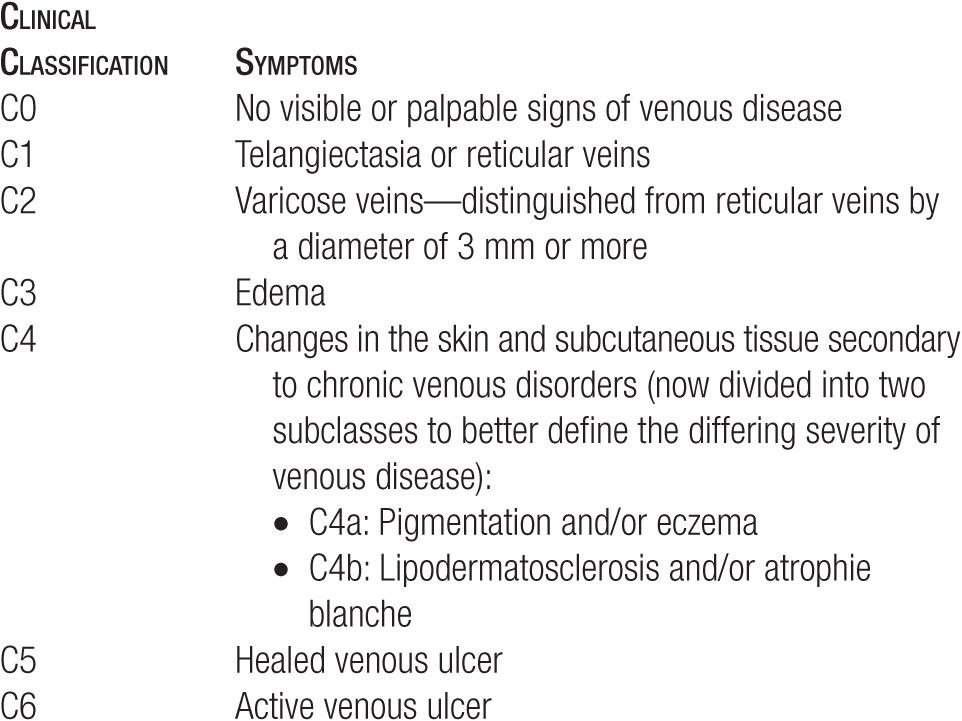

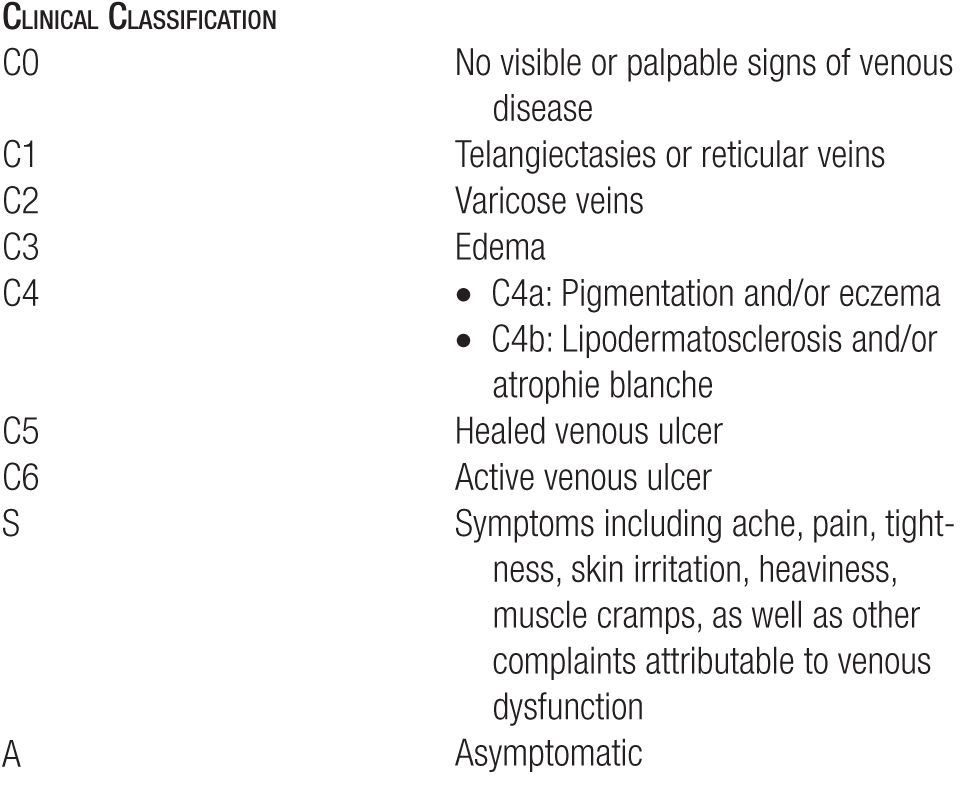

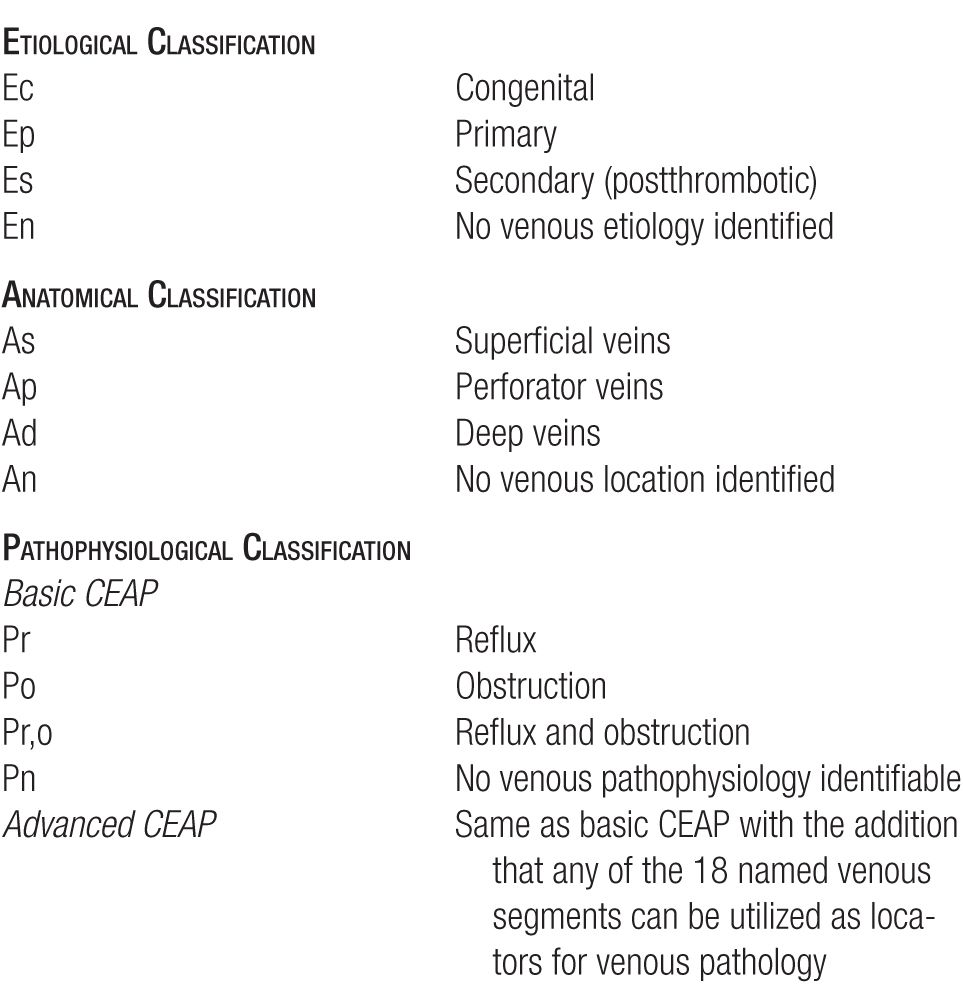

An international committee developed a classification of venous disease, which is known as the CEAP classification.1–3 The acronym CEAP stands for Clinical state (C), Etiology (E), Anatomy (A), and Pathophysiology (P). Clinical symptoms are included as a subclass of S, symptomatic, or A, asymptomatic. The classification is an excellent organization tool but becomes very complex and burdensome for rapid clinical descriptions and will not be utilized in this text as a general rule. For example, a patient with a single branch varicosity of the great saphenous vein could be classified as C2A, Es, As, or Pr. For the initial assessment of a patient, the clinical severity is the most important and can be made by simple observation and does not need special tests. There are seven grades of increasing clinical severity (see Table 1-1). Please refer to Tables 1-1 and 1-2 for a better understanding of this classification system.

TABLE 1-1

Refinement of the Clinical “C” Classes in the (CEAP) Classification

TABLE 1-2

Revision of the Clinical, Etiological, Anatomical, and Pathophysiological (CEAP) Classification

Incidence

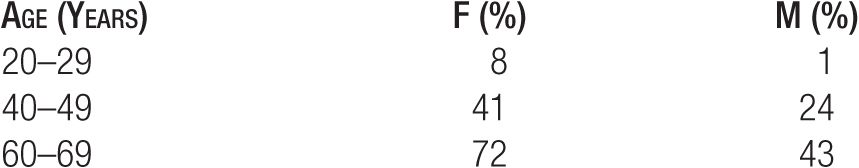

The prevalence of venous disease seems to be higher in westernized and industrialized countries.4 The incidence and prevalence also depend on the age and sex of the population. In the Tecumseh community health study,5 for example, varicosities were observed in 72 percent of women aged 60–69 years but in only 1 percent of men aged 20–29 years (see Table 1-3). As the baby-boom generation ages, the incidence of venous disease per capita has been rising dramatically.

TABLE 1-3

Prevalence of Varicosities by Age and Sex (Data from the Tecumseh Health Study5)

Smaller blue reticular varicosities occur earlier in life, with only a small number of new cases developing after the child-bearing years. Truncal varicosities and telangiectatic webs, on the contrary, are relatively less common in youth and continue to appear throughout life. New varicose veins appear with each advancing decade.

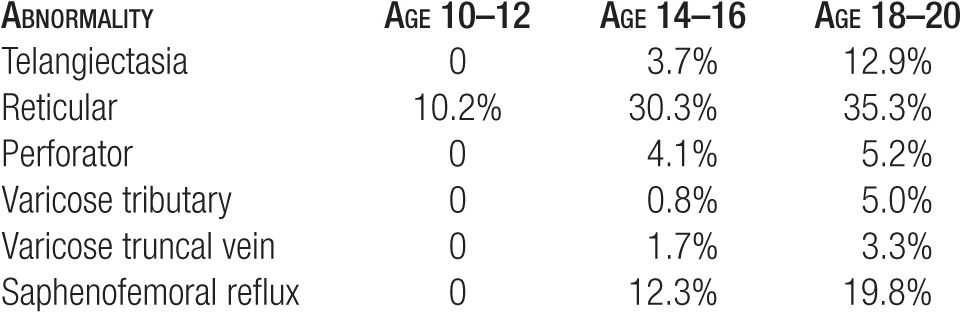

Serial examinations of approximately 500 children at ages 10–12 years and again four and eight years later at ages 14–16 and 18–20 years showed that symptoms are experienced (and venous tests are abnormal) before any abnormal veins are visible at the surface of the skin. Table 1-4 shows that abnormal reticular veins appear first and are followed after several years by incompetent perforators and by truncal varicosities.6,7

TABLE 1-4

Development of Varicose and Telangiectatic Leg Veins by Age (Data from Bochum Study I-III6,7)

Little research has been devoted to telangiectasia. However, the Edinburgh Vein Study analyzed the demographic characteristics of an age-stratified random sample of 1566 people (699 men and 867 women) aged 16–64 years selected from computerized age–sex registers of participating practices to determine the incidence of telangiectasia or spider veins in the general population. A total of 84 percent of the population were classified as having telangiectasias, 79 percent of men and 88 percent of women. The most common locations for telangiectases were the postero-medial aspects of the thigh, popliteal fossa, and upper one-third of calf.8

Etiology of Varicose Veins and Spider Veins

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree