23 Hair restoration

Synopsis

Techniques have evolved in the last 50 years, resulting in more natural (and aesthetically pleasing) hair transplants. The discussion of transplantation refers to micrografts or minigrafts or, more specifically in current nomenclature, follicular grafts.

Techniques have evolved in the last 50 years, resulting in more natural (and aesthetically pleasing) hair transplants. The discussion of transplantation refers to micrografts or minigrafts or, more specifically in current nomenclature, follicular grafts.

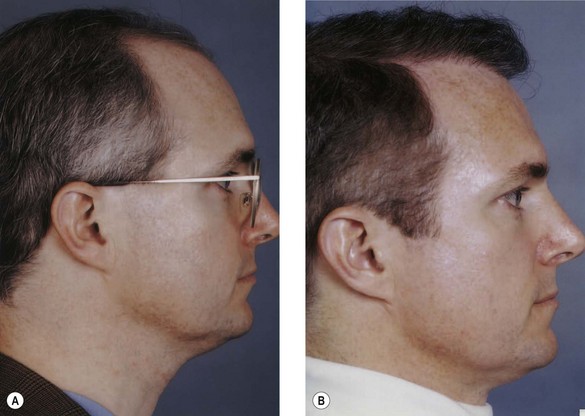

The true objective of hair restoration must go beyond artificial results to a point where the patient who has had hair restoration does not look like he has had any procedure done at all. The final result should be a natural-appearing hairline and natural-appearing density.

The true objective of hair restoration must go beyond artificial results to a point where the patient who has had hair restoration does not look like he has had any procedure done at all. The final result should be a natural-appearing hairline and natural-appearing density.

Rather than continuing the trend of using techniques such as flaps, microsurgery, tissue expansion, and scalp excisions, most surgeons today doing hair restoration have gone to refined, anatomic, naturally occurring miniature grafts in the majority of patients.

Rather than continuing the trend of using techniques such as flaps, microsurgery, tissue expansion, and scalp excisions, most surgeons today doing hair restoration have gone to refined, anatomic, naturally occurring miniature grafts in the majority of patients.

Hair restoration is one of the most common aesthetic procedures performed in the male population.

Hair restoration is one of the most common aesthetic procedures performed in the male population.

Introduction

In order to identify the ideal technique for hair restoration, numerous methods have come and gone during the past 50 years. Most patients undergoing hair restoration today, however, undergo hair transplantation because of the significant refinements of this specific technique. In a patient in whom it is obvious that a procedure such as hair transplant has been performed, the result is less than satisfactory. Techniques such as flaps, excision of bald areas, and expansion no longer dominate this field in the era of small, natural-appearing grafts. The discussion of transplantation refers to micrografts or minigrafts or, more specifically in current nomenclature, follicular grafts. Follicular units refer to the naturally occurring clusters of, typically, one to three hairs that emerge from the scalp.1

Hair restoration is one of the most common aesthetic procedures performed in the male population.2 However, of all the fields of aesthetic surgery, it has suffered one of the worst reputations for producing unnatural results and unhappy patients.

Basic science: anatomy of hair

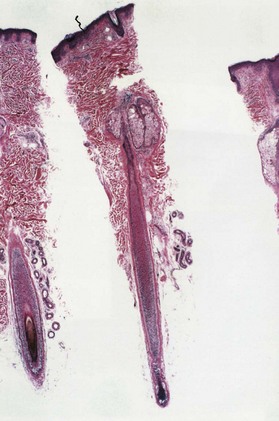

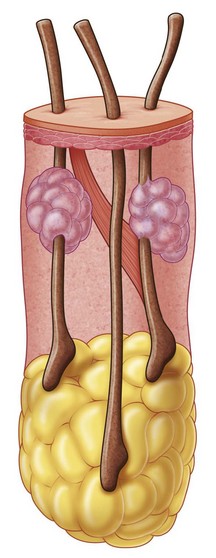

Hair consists of a shaft and a root. The shaft is the visible portion above the scalp surface; its diameter varies from 60 to 100 µm. The three layers of the shaft – the cuticle, cortex, and medulla – consist of keratinized cells. The root or bulb is the follicle and sits at an oblique angle in the scalp (Figs 23.1, 23.2).

Anatomy of a normal hairline

A critical anatomic landmark in the mature male hairline is the frontal–temporal recession. This landmark is formed by the emergence of two convex lines making up the frontal and the temporal hairlines. Design of the frontal–temporal recession is critical to a natural result (Fig. 23.3). A hair restoration in which this rule has not been observed leads to an extremely unaesthetic appearance, especially in the mature adult. Young males usually do not have this recession, and this is one characteristic that distinguishes the child from the adult pattern. As baldness progresses, the frontal–temporal recession increases, forming an acute angle. Both women and children tend to have a continuous line between the frontal and temporal areas without this recession. Another important characteristic of a natural hairline is the transition from fine hair to more dense hair with a degree of irregularity along the margin. Natural hairlines are not straight and regular. Many of the unsatisfactory results in hair restoration demonstrate a fundamental lack of knowledge of these critical points. Other important factors are that the hair follicle sits about 3–3.5 mm below the surface of the scalp and that scalp thickness varies between 5.5 and 6.5 mm. These factors are important in considering the placement of the grafts in the scalp, the thickest layer of skin on the human body.

Hair growth cycles

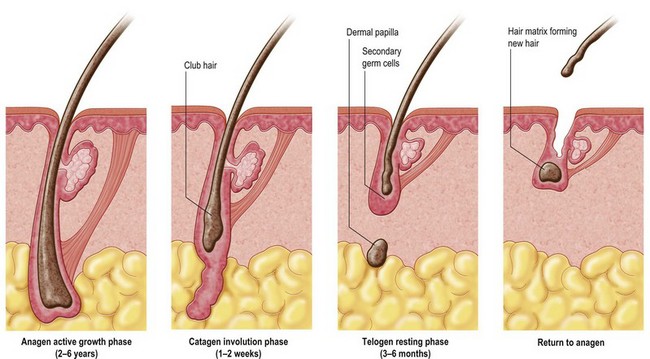

There are essentially three cycles – anagen, catagen, and telogen. During the growth phase, referred to as anagen, the follicular cells are actively reproducing, and matrix keratinocytes are producing cells that differentiate into the different hair components. It is estimated that approximately 90% of the hair on the scalp is in the anagen phase, which lasts approximately 2–5 years. During the regression phase, called catagen, there is a degeneration of the keratinocytes, and special mesenchymal cells, referred to as dermal hair papillae, cluster and separate. This phase typically lasts 2–3 weeks (Fig. 23.4). The final resting phase, called telogen, lasts approximately 3 months. During the 3–4-month phase of telogen, the follicle is inactive and hair growth ceases. Approximately 10% of hairs are in telogen phase at any one time. In the telogen phase, the dermal papilla releases from its epidermal attachment, and eventually there is a reforming of a growing bulb. The old hair is shed, and as the cycle goes back to anagen, a new hair will come up and grow in this area. This information is relevant in discussing hair transplantation with patients. After the follicle has been transplanted, one usually sees a resting or telogen phase, and the patient should not expect any significant hair growth for 3–4 months. Although some of the hairs transplanted occasionally seem to continue to grow immediately after the surgical procedure, this can be misleading. This early growth frequently leads to a shedding of the hair shaft before the telogen phase. Therefore, the patient needs to wait several months before any significant hair growth is seen.

Diagnosis/patient presentation

Types and patterns of baldness

Hair loss in women is frequently of a diffuse nature, and thus, most women may not be ideal candidates for hair restoration. The pattern of hair loss, because of its diffuseness, often results in a lack of appropriate donor hair. However, there is a subgroup of women who demonstrate hair loss similar to the male pattern.3 The hair loss in these women frequently begins at the vertex and progresses anteriorly as they approach their 30s and 40s. The family history in these women is also compatible with a male-pattern type of hair loss, with many of the male and female family members reporting balding in both the vertex and superior portions of the scalp. It is this subgroup of women who may be the most appropriate candidates for hair transplantation because the posterior scalp area has adequate donor hair. The history these women give is fairly typical and is one of slow but progressive hair loss, and it is most evident on the superior scalp with good density on both sides and posteriorly. The other interesting characteristic in many of these women is that they maintain a low frontal hairline with a margin of hair anteriorly. This is unlike the male counterpart with progressive elevation of the frontal hairline and increasing temporal recession as the patient ages. Women with this primary type of alopecia characteristically will maintain that frontal hairline for life, and therefore transplantation needs to begin in this relatively low frontal area and progress posteriorly.

Traumatic alopecia is primarily secondary to ischemia of the hair bulbs, although it can be secondary to direct tissue loss, as in postburn alopecia.4 Numerous factors can lead to this ischemia. Prolonged pressure on the scalp in a single area, such as in a patient who lies in a comatose position for hours at a time, can cause enough ischemia to the scalp that there can be hair loss without loss of the actual scalp soft tissues. In addition, patients undergoing prolonged surgical procedures under general anesthesia can sustain pressure in an isolated area of the scalp, leading to hair loss.

One of the most common causes of traumatic hair loss is aesthetic surgery of the face and scalp area. Temporal hair loss is probably the most common of this group. It may be due to damage of the hair bulb from a subcutaneous dissection in the temporal area or excess skin traction with resulting ischemia. This also is seen in patients undergoing a coronal forehead lift, with hair loss in the area of a coronal scar. In most of these patients, the alopecia is temporary, and hair will regrow after several months. In some patients, however, the hair loss is permanent, and hair transplantation may be appropriate.5,6 In addition, the scar itself in the scalp or facial area may widen, and because of the absence of hair follicles within the widened scar, a visible area of hair loss is seen.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree