Granuloma formation is usually regarded as a means of defending the host from persistent irritants of either exogenous or endogenous origin. Noninfectious granulomatous disorders of the skin encompass a challenging group of diseases owing to their clinical and histologic overlap. Drug reactions characterized by a granulomatous reaction pattern are rare, and defined by a predominance of histiocytes in the inflammatory infiltrate. This review summarizes current knowledge on the various types of granulomatous drug eruptions, focusing on the 4 major types: interstitial granulomatous drug reaction, drug-induced accelerated rheumatoid nodulosis, drug-induced granuloma annulare, and drug-induced sarcoidosis.

Key points

- •

Granulomatous drug eruptions (GDEs) , defined by a predominance of histiocytes in the inflammatory infiltrate, are rare and include 4 major types: interstitial granulomatous drug reaction, drug-induced accelerated rheumatoid nodulosis, drug-induced granuloma annulare, and drug-induced sarcoidosis.

- •

The diagnosis of GDEs is challenging because of the long time lapse between initiation and cessation of the drug, and the emergence and clearance of lesions that usually appear over periods ranging from several weeks to months.

- •

GDEs may be localized to the skin or may include major systemic involvement.

- •

It is reasonable to consider continuing the offending medication in disease limited to the skin if the drug has proved effective in treating a systemic disease, the risks and benefits have been assessed, and proper follow-up is conducted.

- •

GDEs should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of noninfectious granulomatous diseases of the skin.

Introduction

Granulomas represent a pattern of inflammation that develops during the body’s attempt to enclose foreign bodies or inciting agents. The causative agent is walled off and sequestered by cells of the mononuclear phagocyte system, allowing it to be contained, if not destroyed altogether. The mononuclear phagocyte system consists of macrophages, epithelioid cells, and multinucleated giant cells. In most instances these cells are aggregated into well-demarcated focal lesions called granulomas, although a looser, more diffuse arrangement may be found. There is usually an admixture of other cells, especially lymphocytes, plasma cells, and fibroblasts. The characteristics of a granuloma depend not only on the properties of the causative irritant but also greatly on host factors. The granulomatous inflammation is initiated by antigen-presenting cells, which activate T cells to secrete interleukin-2 and interferon (IFN)-γ, which then activate additional T cells and macrophages, respectively. The activated macrophages transform into epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells. Noninfectious granulomatous diseases of the skin are a broad group of distinct reactive inflammatory conditions that share important similarities. As a group, they are relatively difficult to diagnose and distinguish both clinically and histologically. These diseases include granuloma annulare, annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma, necrobiosis lipoidica, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD), sarcoidosis, and metastatic Crohn disease. Granulomatous drug eruptions are an additional rare subgroup of noninfectious granulomatous diseases of the skin. This review summarizes current knowledge on the various types of granulomatous drug eruptions, which include the following types of reactions:

- •

Interstitial granulomatous drug reaction (IGDR), including the subtype drug-associated reversible granulomatous T-cell dyscrasia

- •

Drug-induced accelerated rheumatoid nodulosis

- •

Drug-induced granuloma annulare (GA)

- •

Drug-induced sarcoidosis.

- •

Other granulomatous drug eruptions: cutaneous granulomatous reaction to injectable drugs and vaccinations, photoinduced granulomatous eruption, and miscellaneous.

Introduction

Granulomas represent a pattern of inflammation that develops during the body’s attempt to enclose foreign bodies or inciting agents. The causative agent is walled off and sequestered by cells of the mononuclear phagocyte system, allowing it to be contained, if not destroyed altogether. The mononuclear phagocyte system consists of macrophages, epithelioid cells, and multinucleated giant cells. In most instances these cells are aggregated into well-demarcated focal lesions called granulomas, although a looser, more diffuse arrangement may be found. There is usually an admixture of other cells, especially lymphocytes, plasma cells, and fibroblasts. The characteristics of a granuloma depend not only on the properties of the causative irritant but also greatly on host factors. The granulomatous inflammation is initiated by antigen-presenting cells, which activate T cells to secrete interleukin-2 and interferon (IFN)-γ, which then activate additional T cells and macrophages, respectively. The activated macrophages transform into epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells. Noninfectious granulomatous diseases of the skin are a broad group of distinct reactive inflammatory conditions that share important similarities. As a group, they are relatively difficult to diagnose and distinguish both clinically and histologically. These diseases include granuloma annulare, annular elastolytic giant cell granuloma, necrobiosis lipoidica, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis (PNGD), sarcoidosis, and metastatic Crohn disease. Granulomatous drug eruptions are an additional rare subgroup of noninfectious granulomatous diseases of the skin. This review summarizes current knowledge on the various types of granulomatous drug eruptions, which include the following types of reactions:

- •

Interstitial granulomatous drug reaction (IGDR), including the subtype drug-associated reversible granulomatous T-cell dyscrasia

- •

Drug-induced accelerated rheumatoid nodulosis

- •

Drug-induced granuloma annulare (GA)

- •

Drug-induced sarcoidosis.

- •

Other granulomatous drug eruptions: cutaneous granulomatous reaction to injectable drugs and vaccinations, photoinduced granulomatous eruption, and miscellaneous.

Interstitial granulomatous drug reaction

IGDR, described by Magro and colleagues in 1998, is a rare entity of unknown prevalence, with a peculiar histopathology characterized by the dermal presence of histiocytes between fragmented collagen bundles, leading to the term IGDR.

Etiopathogenesis

The list of drugs capable of inducing IGDR, which includes various groups, is increasing ( Box 1 ). The pathogenesis is unknown. It has been proposed that the drug alters the antigenicity of dermal collagen and elicits an immune response.

Calcium-channel blockers a,

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

Lipid-lowering agents

Brompheniramine (antihistamine)

Histamine H2-receptor antagonists

Furosemide

Carbamazepine

Bupropion and tricyclic antidepressants

Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents: infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, and lenalidomide

Sennoside (laxative)

Herbal medications

β-Blockers

Ganciclovir

Sorafenib (kinase inhibitor)

Strontium ranelate

Febuxostat (selective xanthine oxidase inhibitor)

Anakinra (interleukin-1 inhibitor)

Trastuzumab (immunoglobulin-1 recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody)

Darifenacin (muscarinic receptor antagonist)

a The most common drug inducing the reaction.

Clinical Presentation

The most common cutaneous features are symptomatic erythematous to violaceous annular plaques with a predilection for the flexures (intertriginous areas, medial thighs, and inner aspects of the arms), and, occasionally, indurated borders and central clearing. Other reported clinical presentations include generalized erythematous macules and papules ; erythroderma ; multiple tender, erythematous, violaceous, poorly demarcated, firm papules and plaques on both palms and soles ; and erythema nodosum–like lesions.

Lag period

There may be a prolonged period between the initiation and cessation of the drug and the emergence and clearance of IGDR lesions, ranging from several weeks to months. Twenty patients with IGDR in the study by Magro and colleagues had ingested the offending drugs 4 weeks to 25 years (average, 5 years) before the onset of the eruption.

Differential diagnosis

The erythematous or violaceous plaques in the area of skin folds may mimic the scaly plaques of mycosis fungoides (cutaneous T-cell lymphoma). The differential diagnosis also includes erythema annulare centrifugum, lupus erythematosus, pigmented purpura, lichen planus, dermatomyositis, macular GA, and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis with arthritis (Ackerman syndrome).

Systemic Associations

Characteristically, there is no systemic association in IGDR.

Evaluation and Management

The clinical and histologic findings must be correlated for the diagnosis of this entity. A temporal association between the initiation of drug therapy and lesion onset and resolution after cessation of the implicated drug is characteristic. However, the diagnosis may be challenging because of the prolonged time course between initiation and cessation of the drug and emergence and clearance of IGDR lesions, ranging from several weeks to months. In many cases, the lesions resolve on discontinuation of the drug and reappear on reintroduction of the drug-positive drug provocation test.

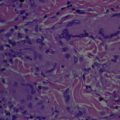

Histology

IGDRs have variable histologic presentations. Microscopically they typically exhibit a diffuse interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes with elastic and collagen fiber fragmentation, vacuolar interface dermatitis, and scant to absent mucin deposition. Tissue eosinophilia is present in most cases. Of note, some 50% of cases exhibit atypical lymphocytes with hyperchromatic convoluted nuclei, found either in the interstitium or along the dermoepidermal junction, with variable epidermotropism. The clinical and histopathologic appearances of IGDR and the granulomatous slack skin variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma are strikingly similar: both present as violaceous plaques on intertriginous areas and show elastolysis, tissue eosinophilia, and granulomatous infiltrates with atypical lymphocytes. In IGDR, however, typical intraepidermal cells do not include Sézary cells and do not exceed the atypia of the dermal component, findings typical of granulomatous slack skin. Other features supporting the diagnosis of IGDR are hypersensitivity reactions, such as papillary dermal edema, vesiculation, basilar vacuolopathy, and dyskeratosis. Differentiation between IGDR and Ackerman syndrome is based on the appearance of vacuolar interface dermatitis with an interstitial histiocytic infiltrate in IGDR.

Treatment

The condition is treated by identifying and discontinuing the drug causing the reaction. Complete resolution of the lesions usually follows the withdrawal of the causative medication. Awareness of this will avoid prolonged disease and unnecessary treatments. In cases where IGDR does not resolve in several months, repeat biopsy is recommended to exclude granulomatous slack skin, and should include gene rearrangement studies. Histopathology suggesting malignancy will require further investigation. The frequent time lapse between the initial ingestion of the offending agent and the onset of cutaneous findings and polypharmacy may further complicate the identification of the culprit. Fifteen of 20 patients with IGDR in the study by Magro and colleagues had 1 or more of the implicated drugs discontinue, and the eruption resolved within 1 to 40 weeks (mean, 8 weeks) in 14 patients with improvement, although not complete resolution, in 1 patient. No recurrences developed at a 12-month follow-up. In the cases of IGDR induced by anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) medications, it is recommended that all patients undergo a careful workup to rule out an infectious process.

A distinct subset of the IGDR is drug-associated reversible granulomatous T-cell dyscrasia, a novel reaction pattern characterized by atypical T-lymphocytic infiltrates that manifest a light microscopic, phenotypic, and molecular profile that closely parallels cutaneous T-cell lymphoma but regresses when the causal drug is withdrawn. Margo and colleagues labeled this distinct subset in 2010 based on a series of 10 patients with atypical cutaneous T-cell lymphocytic infiltration associated with granulomatous features, and combined light microscopic, phenotypic, and molecular profile resembling a subtype of mycosis fungoides, which they designated granulomatous mycosis fungoides. The cutaneous findings included persistent eczematous papules, plaques, or patches, or infiltrative plaque-like lesions, often in fold areas of the skin, which resolved or mostly resolved following discontinuation of the offending drug in 2 weeks to 10 months. In all cases the biopsies showed a diffuse interstitial lymphocytic and histiocytic infiltrate. Other histologic findings in these cases included epidermotropism, and angiocentric infiltrates containing large transformed cells and cells with an atypical cerebriform morphology. All cases showed a dominance of CD4 cells over those of the CD8 subset. There was a reduction in the expression of CD7 in most cases and, in a few cases, CD62L expression of greater than or equal to 50%. The large transformed cells in an angiocentric array showed CD30 expression. Molecular studies demonstrated clonality at 2 different biopsy sites in one case, oligoclonality in another, and a polyclonal profile in the remainder. In one case where clonality was identified in the skin biopsies, the peripheral blood analysis showed an oligoclonal profile without any commonality between the dominant clones detected in the peripheral blood and those detected in the skin. One patient continued to have a peripheral blood monoclonal T-cell population despite the absence of skin lesions, indicating the importance of drug modulation to prevent the conversion of what is initially a reversible T-cell dyscrasia to one that may become irreversible.

Drug-induced accelerated rheumatoid nodulosis

Etiopathogenesis

Kremer and Lee first noted accelerated rheumatoid nodulosis in 1986 during a study of long-term methotrexate (MTX) therapy for rheumatoid arthritis (RA). In 2001, Ahmed and colleagues termed this acceleration MTX-induced accelerated rheumatoid nodulosis (MIARN). Other medications have been implicated in accelerated rheumatoid nodulosis ( Box 2 ). However, as MTX is the most common drug to be associated with this condition, this section focuses on MIARN. A double-blind study that compared MTX and azathioprine in patients with refractory RA showed an 8% incidence of MIARN (with arthritic improvement) and none with azathioprine. Other collagen vascular diseases besides RA were associated with accelerated rheumatoid nodulosis, including juvenile RA, psoriatic arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus. Although the mechanism of accelerated nodulosis is unclear, studies have suggested a genetic etiology or, at least, predisposition. In 2001, a retrospective study of 79 Caucasian patients with RA identified the HLA-DRB1*0401 allele as an HLA class II gene that associates with nodule formation. A 2007 cross-sectional study identified a polymorphism of the methionine synthase reductase gene in RA patients that was increased in these patients in comparison with the general population and was associated with MIARN. Of interest, accelerated rheumatoid nodulosis does not appear in patients receiving MTX therapy for disorders other than collagen vascular diseases (eg, patients with psoriasis). Therefore, it seems possible that there is a synergistic pathogenic effect between the underlying collagen vascular disease and the drug inducing the nodulosis.

Methotrexate a,

Anti-TNF agents: etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab

Aromatase inhibitors

Azathioprine

Leflunomide

a The most common drug inducing the reaction.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical presentation of MIARN includes multiple flesh-colored to erythematous indurated papules and nodules. MIARN affects mainly the hands, usually the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints, although other locations have been reported including knees, heel pads, Achilles tendons, arms, elbows, thighs, shoulder girdle, buttocks, and feet. The nodules are typically painful, but discomfort is minimal in most patients. Regarding the clinical presentation of accelerated rheumatoid nodulosis induced by drugs other than MTX, Cunnane and colleagues reported 3 patients with refractory seropositive erosive RA who, despite clinical improvement with etanercept, developed new nodulosis, 2 cases of cutaneous nodulosis, and 1 case of pulmonary nodulosis. Scrivo and colleagues reported on a patient with RA who developed subcutaneous nodules in the extensor side of the elbows following treatment with adalimumab. Mackley and colleagues reported a patient with seropositive RA who developed nodules on the fingers of both hands despite continued remission of her rheumatoid arthritis following treatment with infliximab. Chao and colleagues described a patient with RA who developed subcutaneous nodules on the fingers of both hands following treatment with an aromatase inhibitor. Langevitz and colleagues reported on a patient with seropositive, erosive RA who developed subcutaneous nodules on the elbows and extensor surfaces of the arms and hands during treatment with azathioprine. Three patients reported by Braun and colleagues developed subcutaneous nodules on the extensor side of the hands and elbows following leflunomide therapy.

Lag period

Nodule formation is not related to cumulative MTX dosage. The duration of MTX therapy reported before MIARN ranges widely from hours to months. In a retrospective study by Ahmed and colleagues, of 30 cases with MIARN the mean duration of MTX therapy was 36.4 ± 27.2 months before developing MIARN.

The lag period reported with medications other than MTX that induce accelerated rheumatoid nodulosis is as follows. Anti-TNF agents: 2 to 3 months for etanercept, 26 months for adalimumab, and 12 months for infliximab ; aromatase inhibitors, 15 months ; azathioprine, 1 month ; and leflunomide, 6 months.

Differential diagnosis

Rheumatoid nodules comprise 3 clinical types: classic rheumatoid nodules associated with RA, rheumatoid nodulosis, considered a benign variant of RA, and MTX-induced rheumatoid nodulosis. Differentiation between these types of nodules may be challenging. MIARN is characterized by multiple lesions that disappear with termination of MTX and do not recur in previously affected areas in the absence of MTX therapy. The differential diagnosis also includes pseudorheumatoid nodules, cutaneous extravascular necrotizing granuloma of Churg-Strauss, and rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatitis.

Systemic Associations

One patient in the report by Ahmed and colleagues developed lung disease with biopsy-proven intrapulmonary nodules that resolved completely after MTX withdrawal. Another patient developed extensive cutaneous nodulosis associated with new cardiac murmurs of aortic and tricuspid regurgitation. Other reported organ involvement includes the lungs, heart, and brain.

Evaluation and Management

Histology

Nodules have a histology similar to that of rheumatoid nodules : multinodular foci of massive necrobiosis with adjacent scarring in soft tissue or subcutaneous fat, surrounded by a histiocytic palisade, with fibrin deposition, often seen with rosettes of histiocytes surrounding collagen bundles in the reticular dermis. In 4 cases with cutaneous lesions caused by methotrexate therapy (2 with systemic lupus erythematosus, 1 with RA, and 1 with Sharp syndrome), histopathology of the papules showed an inflammatory infiltrate composed mainly of histiocytes interstitially arranged between collagen bundles of the dermis, intermingled with few neutrophils. Some foci of deeper reticular dermis contained small rosettes composed of clusters of histiocytes surrounding a thick central collagen bundle.

Treatment

MIARN often regresses with discontinuation of MTX and reappears once MTX is restarted. in the report by Ahmed and colleagues, nodules regressed within 6.1 ± 4.5 months when MTX was discontinued but persisted for 41.2 ± 14.9 months when MTX was continued. It was suggested that unless the nodules are painful or interfere with the patient’s usual activities, MTX therapy may be continued, especially if the arthritis has improved. The addition of hydroxychloroquine, etanercept, d -penicillamine, and colchicine have been shown to accelerate healing in cases where MTX was continued. Discontinuation of MTX and aggressive intervention may be warranted with development of symptoms, ulceration, infection, or mechanical issues.

In the cases of accelerated rheumatoid nodulosis induced by drugs other than MTX, treatment included discontinuation of the offending drug, changing the dosage of the offending drug, adding an immunosuppressive drug, and not changing or adding any treatment.

Drug-induced granuloma annulare

Etiopathogenesis

GA is a benign, self-limited disorder of unknown etiology, first described by Colcott-Fox in 1895, and named granuloma annulare by Radcliffe-Crocker in 1902. GA has various clinical variants, including localized, generalized (generalized annular GA, disseminated papular GA, and atypical generalized GA), subcutaneous, and perforating, providing for a wide spectrum of clinical lesions. Several systemic associations have been proposed but not proven, including diabetes mellitus, malignancy, thyroid disease, and dyslipidemia. The first association between GA and drugs was reported in 1980, since then various drugs have been implicated in its etiology ( Box 3 ). The pathogenesis of drug-induced GA is not known, although the possible role of immune dysregulation induced by immunosuppressive drugs has been suggested. Several cases of TNF-α antagonists inducing GA were reported, a curious finding given that TNF-α inhibitors can be used for the treatment of refractory GA. The pathogenesis of TNF-α antagonist–induced GA may be related to the autoimmune phenomena induced by anti-TNF-α therapy in genetically predisposed individuals.

Anti-TNF agents a : infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, thalidomide

Amlodipine

Gold

Allopurinol

Diclofenac

Intranasal calcitonin

Immunizations (hepatitis B and antitetanus vaccination)

Paroxetine: drug-induced photodistributed granuloma annulare

Pegylated interferon-α

Desensitization injections

Topiramate (anticonvulsant)

a The most common drug inducing the reaction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree