The Epidemiology and Burden of Skin Disease: Introduction

The word “global” describing something that is worldwide is not a concept that is difficult to understand, whereas the term “health” is frequently misused on the assumption that it simply means freedom from disease. However, health and disease are not merely examples of the converse, a point that is captured by the mission statement of the World Health Organization (WHO), whose objective is to promote health. The WHO definition of health, which is widely used as the definitive descriptor of health, says that health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. Therefore, global health implies a worldwide mission to promote complete well-being.

Health and Global Interdependence

The rational basis for this idea is simple as no nation or region is a complete island in terms of health; what affects one country may well, in time, affect another. The most obvious examples of this concept from past history involve the spread of infections. At present, there is a concerted effort to follow the international spread of HIV or avian influenza. Both present global risks to health, which is the reason why their current distributions are tracked regularly and with accuracy.1 Spread of these diseases has occurred and will continue to occur through a combination of both social and economic factors and the movement of populations and individuals. Yet historically, infectious diseases that have spread rapidly to cause maximum chaos have often resulted from a relatively minor, and often unrecognized, episode rather than a large movement of individuals. For instance, the impact that a localized outbreak of bubonic plague had on medieval Europe when the besieged Genoese garrison in Caffa, in the Crimea, fled by ship bringing the rat host with them was not foreseen.2 The subsequent epidemic, caused by Yersinia pestis, known as the Black Death, reduced the population of Europe by a third over the following 2 years. In addition to the mortality and distress, it resulted in profound social and economic changes that long outlived the epidemic itself. Predicting and tracking the international course of infections is now a key element of global surveillance.

However, global health problems and disease are not limited to infections, although the propensity to spread is more demonstrable in this group; chronic noninfectious conditions are also global. The relentless increase in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus type 2 in aging populations is such an example. Global health is affected by other factors that include the impact of social, economic, and environmental change on populations. This reflects the fact that human populations are no more isolated socially than they are geographically, but manifest a measure of interdependence where what happens in Kazakhstan may be reflected, in time, in New York City. In the case of diabetes, the causes of changes in health status are different; the international dissemination and adoption of Western dietary behaviors are, at least partly, responsible for this. Health-determining trends such as diet, lifestyles, or global warming are all examples of noninfective risk factors that may affect global health. The international spread of risks to health may follow different routes, often simultaneously.

In many parts of Europe and the United States, the decline of tuberculosis was a marker of economic progress in the twentieth century,3 the main reduction in disease incidence, and subsequently mortality, preceding by many years the development of new specific treatments such as streptomycin or the introduction of BCG immunization. This health improvement reflected the huge social changes made during this era, such as the provision of sustainable and affordable water supplies and drainage, heating schemes, better housing, and nutrition. While the increasing prosperity and subsequent social reforms that affected the industrialized Western nations in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had a huge impact, mainly for the good, in promoting better health, in international terms the benefits were relatively restricted and not global in their reach; large areas of the world did not benefit from this change. In the recent report by Michael Marmot,4 the continuing influence of social and economic conditions on both national and global health are clearly demonstrated and poor social and economic status linked closely to poor health indicators such as high maternal and infant mortality. He cites Sweden as an example of a country that has adopted a policy where the creation of appropriate social conditions would ensure the health of the nation. Much of this health initiative concentrates on social initiatives such as improvement of participation, economic security, and healthy working. This type of policy has been supported in both rich and poor countries. For instance, the Mexican initiative, Programa de Educacion, Salud y Alimentacion (Progresa), which provides financial incentives for families to adopt measures that will ensure social improvements leading to better health, is a good example.5 While this may seem oversimplistic, poor health is often an indicator of social ills and vice versa; the two are interdependent. Health can make a significant impact on both micro- and macroeconomics; conversely economic performance has a direct impact on health. The WHO report on macroeconomics and health6 asserted the view that the investment of both time and money on health improvement had multiple benefits through reduction of mortality and increase in the healthy employed, measures that would lead to improvement in both family and national economics. By ensuring good health of their populations nations would improve economic performance and social conditions, which, in turn, would improve health status of their peoples. So good health is an important facet of social and economic development, just as poor health is an indicator of poor performance in both domains. Therefore, global health becomes an important social aspiration in a world where international collaboration and interdependence as well as increasing global industry are slowly replacing, or at any rate adding another dimension to, the nation state.7

Global Burden of Disease Project

In order to determine the impact of global health, a consortium of international bodies such as the World Bank in 1990 commissioned a report on the global burden of disease (GBD); a project that has now gone through several iterations involving other organizations, including WHO and an international group of universities.8 In doing this work, there were two key objectives, namely: (1) to provide up-to-date information on the incidence of disease states in all the regions of the globe and (2) to assess their impact on mortality and disability. In carrying out this work, the interdependence of health and social and economic well-being was clearly recognized. These large surveys of global disease have had to draw on the availability of studies that can provide the necessary information. A subsequent development from GBD, aimed at health in developing countries, was the Disease Control Priorities Project (DCPP), an international report focusing on sustainable measures of disease elimination or control.9 The latest GBD round of studies is incomplete at the time of writing.8 However, it differs from other studies in that much of the work of collecting data is the task of specialist groups, including one for dermatology. The target is to provide data covering diseases and risk factors (such as consumption of alcohol or atmospheric pollution) in the WHO designated regions and, where this is missing, to provide robust means of adducing the data using defined mathematical models. The study aims to target disease incidence at two time points—(1) 1990 and (2) 2005. It will also provide measures of mortality as well as disability. The methods used to assess the latter is more refined than previously in that lay panels (i.e., patients) will be asked to assign the weighting that determines the disability that accompanies disease states.

Global Health and the Skin

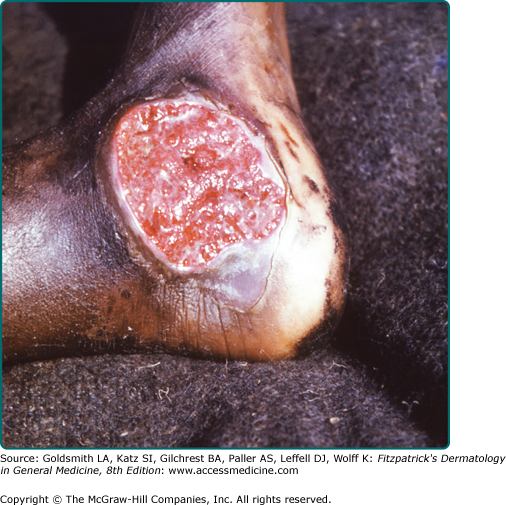

Within this international perspective, there is a similar connection between global health, dermatology, and the spread of skin disease. Dermatology is subject to the same factors that regulate the spread of other diseases and determine its control; infection, social, and economic factors are all important in determining the prevalence and impact of skin disease.10 Skin infections are very common in all societies; tinea pedis (athlete’s foot), onychomycosis, scabies and childhood pyoderma, viral warts, and recurrent human herpes virus (HHV1) are all examples of everyday skin infections that affect many people. There are also examples to show that this spread is mediated by human contact and, where there is facility for this to occur, for instance, in a swimming pool in the case of human papilloma virus infections of the feet and tinea pedis, there is a higher incidence of disease.11 Likewise, movements of numbers of individuals through travel, migration, or war increase the chance of global spread of these infections. For instance, the world diffusion of infection due to Trichophyton rubrum is said to have followed the displacements of populations and the movement of soldiers in the 1914–1918 and 1939–1945 wars.12 More recently, the spread of Staphylococcus aureus bearing the Panton–Valentin leukocidin (PVL) virulence gene causing furunculosis has been tracked, in some cases, to international travel.13 Despite this, in some parts of the world there are still unique and geographically localized skin infections, largely because these occur in remote areas. The lower limb infection of children and young adults seen in remote regions of the developing world where there is a high rainfall, tropical ulcer (Fig. 3-1), is an example of a condition that has remained relatively isolated14; the fungal infection of the skin, tinea imbricata, is a further example.15 However, even where there is relative isolation, changes over time such as migration can lead to epidemic spread of previously endemic disease. Tinea capitis has undergone a remarkable transformation in the Western hemisphere in the past 50 years. It has seen the introduction of an effective treatment regimen with griseofulvin initially and subsequent decline in infection rates followed by the relentless spread of one dermatophyte fungus, Trichophyton tonsurans, initially from a zone of endemic disease in Mexico, where it still remains as a stable infection of moderate incidence, to reach epidemic proportions in children in inner cities, initially in the United States, but subsequently in Canada, Europe, the West Indies, and Latin America.16 The spread appears to follow an increased susceptibility to infection of children with African Caribbean hair type; in recent years it has begun to spread in Africa as well.

In a similar way, noninfectious skin disease, as with other illnesses, is also affected by those social and economic changes that are international in dimension. The complex history of the medical reaction to the fashion for sun exposure was formed initially by the recognition of the health promoting, and then health limiting, effects of sun and ultraviolet (UV) light.17 The current concern over excessive exposure to both natural sun or UV exposure, for instance, in sunbed parlors, or as part of UV therapies, is an important stage in an exercise that started as genuine attempt at health promotion. The ancient Greeks, for instance, promoted sun exposure or heliotherapy as beneficial for a number of medical problems.3 While largely ignored for the best part of two millennia the revolution in medical ideas in the nineteenth century led to sun exposure being adopted as a health-giving practice with the discovery of Vitamin D and the award of the Nobel Prize to Finsen for light therapy. Health-giving sun exposure was adopted widely and became a fashion that was the rage of the health conscious, delivered in spa environments such as William Kellogg’s Battle Creek clinic.18 However, the habit, perhaps fueled by the recognition that exposure to natural light was in some ways health giving, led inevitably to one of the consequences, the sun tan. It is not certain if the recognition of the sun-tanned skin as fashionable can all be laid at the door of Coco Chanel, who is said to have been overexposed to the sun during a holiday in Cap Antibes in France. The resulting effect on her skin color was soon to be adopted by the fashionable and white wherever they lived.19 Soon it became a global trend in fashion. The recognition that sun exposure also led to a rising incidence of skin cancer followed more slowly, but perhaps with greater speed than that concerned with the connection between smoking and lung cancer. Protection against sun exposure has become a major global focus of preventive measures of public health medicine, from public education to the risks involved to early detection of melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers. Dermatological organizations have reacted with admirable speed to the recognition of the risk of UV exposure. This has been accomplished through seminars, magazine articles, public health campaigns, and training camps. The introduction of educational programs in schools has been a welcome addition.

The trend to the opposite, skin lightening, in women of color has been an equally global trend where the use of skin bleaching products has been adopted by different cultures throughout the world. The common agents in use include hydroquinone- or steroid-containing creams—with a resulting risk of the development of skin disease such as ochronosis and more general medical problems, including low birth weight infants in pregnant women using topical corticosteroids to achieve lightening.20 As with infections, there are also examples of skin diseases that are caused by social customs or economic conditions that remain geographically localized. Erythema ab igne of the forearms is almost unknown in most parts of the world but is associated with the cooking of tortillas (enfermedad de las tortilleras)—so it is only seen where the tortilla is a staple of diet; oral submucous fibrosis occurs where the Betel nut is chewed is another example. However, some noninfective skin conditions occur in isolated communities for a different reason, genetic susceptibility, such as actinic dermatitis seen in native American communities in North and South America (Fig. 3-2). These are not the only examples of the relation between noninfectious skin disease as an international concern and social and economic factors. One of the earliest public health campaigns that crossed national boundaries stemmed from the recognition that industrial workers exposed to oil during the operation of large-scale spinning were susceptible to skin cancer and the ingestion of arsenic at work or as a medication was also potentially harmful through the development of skin cancer.21 Recently, much international interest has focused on the changing face of atopic dermatitis and although the evidence suggests that this is a condition associated with societies enjoying improved socioeconomic status,22 the quest for modifiable risks whose resolution may, in turn, provide benefit to children with this condition is now the subject of a global initiative (the ISAAC study).

So skin disease is subject to different, but nonetheless global influences, compared with other illnesses and in the pursuit of skin health there is a great need to promote international cooperation. This objective is identified, not just in order to share learning experiences, but also because the burden of skin disease is spread unequally around the world and many of the poorest nations face the greatest problems.9 Here, the social and economic factors plus uncontrolled or poorly controlled infection play key roles in determining the pattern of disease.

Skin Disease in Resource Poor Environments

In the poorest countries skin disease usually ranks as one of the first three common disorders encountered in frontline medical facilities, i.e., the first point of call for a patient seeking treatment. Whereas in the developed countries many of the problems facing dermatologists and primary care practitioners are noninfectious skin diseases, the opposite is true in developing countries where infections dominate the pattern of presentation.23

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree