Fig. 30.1

Penile and scrotal lymphedema (a) 14-year-old male with isolated scrotal lymphedema. (b) 15-year-old male with combined penile and scrotal lymphedema. (c) 17-year-old male with a central conducting lymphatic anomaly and associated penile and scrotal lymphedema. (d) 15-month-old male with congenital lymphedema–distichiasis involving his penis

Fig. 30.2

Labial lymphedema. (a) 7-year-old female with a generalized lymphatic anomaly and associated right lower extremity and right labial lymphedema. (b) 29-year-old female with left-sided lymphedema and bilateral labial involvement

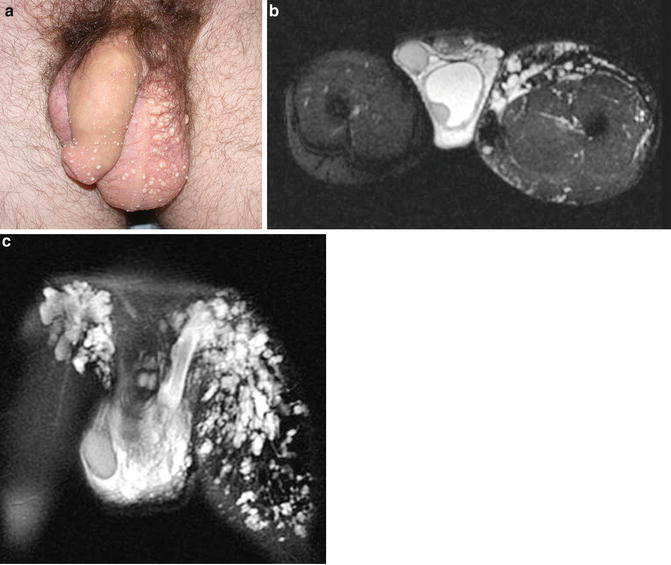

Fig. 30.3

(a) 27-year-old male with a central conducting lymphatic anomaly and associated combined penile and scrotal lymphedema as well as cutaneous lymphatic malformations. This patient had chyle leakage from the cutaneous penile and scrotal vesicles and had experienced numerous bouts of scrotal cellulitis. (b) T2-weighted fat/sat axial and (c) coronal MRI images depicting lower extremity and scrotal lymphatic malformations

Obstruction, malformation, or dysfunction of the central conducting lymphatic channels (cisterni chili, thoracic duct, and accessory thoracic duct) can lead to lymph reflux and manifest as pulmonary and pericardial effusions, ascites, and sometimes vaginal or scrotal lymphedema. Patients may even present with leakage of chylous fluid from the genitalia [9, 17]. Isolated lymphatic malformations are most commonly located in the neck, axilla, chest wall, and pelvis [18], but can also be found within the genitalia. Lymphatic malformations are classified as macrocystic, microcystic, or combined [19, 20].

Complications associated with primary genital lymphedema include lymphorrhea, chyluria, hematuria, and cellulitis. Cellulitis has the potential to be life threatening and should be treated aggressively. Patients with scrotal or vaginal cutaneous lymphatic malformations are also at an increased risk of developing cellulitis, as the abnormal lymphatic channels act as a portal of entry for bacteria. Another common complication of lymphatic malformations is intralesional bleeding. This typically presents with the acute development of swelling and pain. Hematuria or chyluria can be seen in patients with lymphatic malformations along the urethra or bladder wall.

Diagnosis

Genital lymphedema is an uncommon but troubling cause of deformity of the male and female genitalia. While most patients develop symptoms in infancy or early childhood, the diagnosis is often delayed for several years. Lymphedema is most commonly confused with other vascular anomalies, particularly if the lower extremities are also affected. An accurate diagnosis is imperative in providing appropriate counseling and treatment. History and physical examination are the primary mode of diagnosis, followed by imaging in limited cases. A detailed history should document when the lymphedema first developed and also rule out causes of secondary lymphedema such as infection, trauma, prior radiation, or prior surgical procedures. A family history should also be obtained, as genital lymphedema can be part of inherited diseases such as Noonan syndrome, lymphedema–distichiasis, or Milroy disease [11, 14]. Some patients with concomitant lower extremity manifestations will have had confirmatory lymphoscintigraphy prior to referral. Delayed transport and/or dermal backflow of radiolabeled colloid indicate lymphatic dysfunction with 92 % sensitivity and 100 % specificity [21]. Ultrasonography is less specific and CT exposes the reproductive organs to radiation and should therefore be avoided. MRI can help distinguish lymphedema from other vascular anomalies, such as venous or lymphatic malformations, and can also be of value in operative planning. Patients with a central conducting anomaly may benefit from lymphangiography as this study may localize the lymphatic blockage or abnormality. Biopsy should be utilized only if malignancy or other conditions, such as noninfectious granulomatous disease, are suspected.

Treatment

Once the diagnosis of genital lymphatic disease is made, treatment should be initiated. Genital lymphatic disease can adversely influence a patient’s quality of life, affecting both their functional and emotional well-being. While many patients do not have symptoms beyond enlargement of the genitalia, the psychosocial consequences of disfigurement should not be underestimated, particularly as a child becomes aware of genital anatomic differences in adolescence. Emotional health should be routinely screened in all patients as referral for a formal psychiatric assessment may be indicated in some patients.

Conservative Management

Patient education is key in managing genital lymphedema. Infection prevention is of great importance. Daily washing of the genitalia and application of a moisturizing agent to prevent skin breakdown should be emphasized. The patient and family should be taught to recognize signs or symptoms of cellulitis as this complication can be life threatening. Treatment with oral or intravenous antibiotics should be initiated promptly once cellulitis is diagnosed. Prophylactic low dose antibiotics should be considered in patients who have had three or more episodes of cellulitis in a year. Patients with lymphatic malformations also are at an increased risk of infection and should practice good hygiene. Patients with lymphatic malformations can develop intralesional bleeding, which is often painful, and difficult to manage. The bleeding is often self-limiting and is treated with compression and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications. Lymph leakage from cutaneous lymphatic vesicles or from the genitalia of patients with central conducting anomalies should be kept dry. Patients can apply absorbent pads to affected areas. Cutaneous lymphatic vesicles, particularly on or near the genitalia, act as a portal for bacterial entry and can be aggressively treated with CO2 laser ablation of the lesions [22] and or sclerosis of macrocystic lymphatic channels [23]. Often with CO2 laser treatments, multiple sessions are required to create enough scar tissue to slow or stop lymphatic leakage. Sclerosis near the meatus or urethra runs the risk of causing a stricture and should only be attempted by experienced clinicians. Sclerotherapy within the scrotum may also risk damage to the testicles.

Initiation of compression therapy with compression garments, pneumatic devices, or fitted clothing is the mainstay of nonoperative treatment in patients with lower extremity and genital lymphedema [1, 23]. Patients with lymphatic malformations and central conducting anomalies affecting the genitalia may also benefit from compression therapy. Due to the shape and location of genital lymphedema, wrapping and stocking material can be difficult to apply and may require ingenuity on behalf of the patient and family (Fig. 30.4). Another consideration is that applying compression devices to a growing infant is challenging and often not feasible. Elastic shorts may be a good option for older patients. Some patients apply wedge under the pelvis to elevate the genitalia while sleeping to improve lymphatic return. The benefits of compression therapy and elevation need to be weighed against the inconvenience this causes the patient. Our institutional experience has shown that when tolerated, compression therapy is useful in maintaining and at times reducing genital size. Postoperative penile wrapping is particularly effective at reducing the risk of recurrent swelling.

Fig. 30.4

13-year-old boy with congenital lymphedema involving his penis. (a) Penis is shown unwrapped (Left) and wrapped circumferentially (Right) with Kerlix gauze

Operative Intervention

Surgical treatment of genital lymphedema is indicated for patients with significant disfigurement or morbidity that have failed nonoperative management. Operative indications include excessive mass, functional impairment, and/or disfigurement. Operative intervention for female genital lymphedema is rare. It is preferable to wait until the child has completed puberty and is fully developed before attempting to debulk excess tissue. For extreme cases of genital lymphedema, conservative early debulking can be performed, with the expectation of potential additional intervention when the child is older. Patients and their families should be counseled regarding expectations. While disfigurement can be greatly improved, the genitalia will likely never appear completely normal. The point that operative intervention will not impair function or reproductive capabilities if done correctly should be emphasized. At our center we employ excisional intervention for both penile and scrotal lymphedema. The goal of the procedures is to excise lymphedematous tissue as well as removal of the redundant overlying skin. Alternate surgical approaches have been previously described with different incisions without removing redundant skin [24–26

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree