Chapter 16

Fungal Infections

OVERVIEW

- Fungi can cause infections of the skin, hair, nails and orogenital tract.

- Fungal infections are more common in hot climates and in immunosuppressed individuals.

- A diagnosis of fungal infection is usually made clinically; however, it may be confirmed by culture of skin scrapings/scalp brushings.

- Tinea capitis usually needs to be treated with systemic antifungals.

- Onychomycosis (fungal infection of the nails) affects mainly adults and may be chronic.

- Candida (yeast) causes lesions in the mucous membranes and flexures where it should be differentiated from psoriasis, seborrhoeic dermatitis and contact dermatitis.

- Deep fungal infections may occur in diabetics, neutropenic, debilitated patients and the immunosuppressed.

Introduction

One million species of fungi are currently recognised, of which 300 are pathogenic to humans and of these over three-quarters primarily infect the skin and subcutaneous tissues. Superficial fungal pathogens are the fourth commonest cause of any human disease worldwide. Historically, superficial fungal infections have caused minimal disease in temperate climates, with the most severe outbreaks occurring in the tropics and subtropics. The use of potent immunosuppressant and antimicrobial drugs has increased the incidence of fungal infective episodes in temperate climates. Currently, there is emerging resistance to antifungal medications and to date no human fungal vaccine exists.

Some fungi live on the skin as part of the normal skin flora while others come into contact with the skin through the environment and animals. Superficial fungal infections attack the epidermis, mucosa, nails and hair, and are divided into two groups: moulds (e.g. dermatophytes) and yeasts (e.g. Candida).

Yeast that comprise part of the normal skin flora can become pathogenic because of a change in the host’s immune system. This allows the yeast to disseminate throughout the body, causing serious life-threatening disease. Conversely, mycoses that originate as systemic infections can become deposited in the skin via haematogenous spread.

Investigations

Diagnosis of fungal infections can be made by taking skin scrapings, nail clippings, scalp brushings and skin biopsies for mycological analyses (Box 16.1). A moistened bacterial swab taken from the affected skin and inoculated into standard fungal media can be a useful additional test. Expert mycologists who perform fungal microscopy may be able to make an immediate diagnosis through recognition of characteristic fungal features. Macroscopic patterns of fungal growth from cultures may also lead to species diagnoses; however, fungi are usually slow to grow. Modern fungal diagnostics are moving towards the use of rapid PCR tests and ELISA, which can rapidly process numerous specimens simultaneously. Some mycology reference laboratories may also be able to provide a sensitivity profile to antifungal drugs from any fungal strain isolated.

Box 16.1 Principles of diagnosis

- Consider a fungal infection in any patient with itchy, dry, scaly lesions (usual distribution is asymmetrical).

- Skin samples are taken by scraping the edge of the lesion with a blunt blade held at right angles to the skin and collected onto a piece of dark paper

- Nail clippings should be taken from the nail including subungal debris.

- Scalp brushings should be taken from the scalp (a travel toothbrush can be used).

- Laboratories will report initially on direct microscopy but culture results take 2–4 weeks.

- Lesions to which steroids have been applied are often quite clinically atypical because the normal inflammatory response is suppressed—tinea incognito.

- Wood’s light (ultraviolet light) can reveal Microsporum infections of hair, as they produce a green-blue fluorescence.

General features of fungi in the skin

Superficial dermatophyte infections are named according to the body site affected: tinea capitis (scalp), tinea corporis (body), tinea cruris (groin) and tinea pedis (feet). Fungal infections invariably cause itching; the skin may be dry and scaly or in flexural areas wet maceration can result.

Zoophilic (animal) fungi generally produce a more intense inflammatory response with deeper indurated lesions (Figure 16.1) than fungal infections due to anthropophilic (human) species. Some lesions have a prominent scaling margin with apparent clearing in the centre, leading to annular or ring-shaped lesions—hence the term ‘ringworm’.

Figure 16.1 Animal ringworm.

Children below the age of puberty are susceptible to scalp ringworm, termed tinea capitis. In many inner city areas the most common fungus isolated is caused by a human species Trichophyton tonsurans, but fungi from animals (cattle, dogs, and cats) may also occur. Infection from dogs and cats with a zoophilic fungus (Microsporum canis) to which humans have little immunity can occur at any age (Figure 16.2). Adults typically are more commonly affected by tinea pedis. Tinea cruris in the groin is seen mainly in men, and fungal nail infections (onychomycosis) are particularly common in the elderly and debilitated.

Figure 16.2 Tinea capitis: Microsporum.

Scalp and face

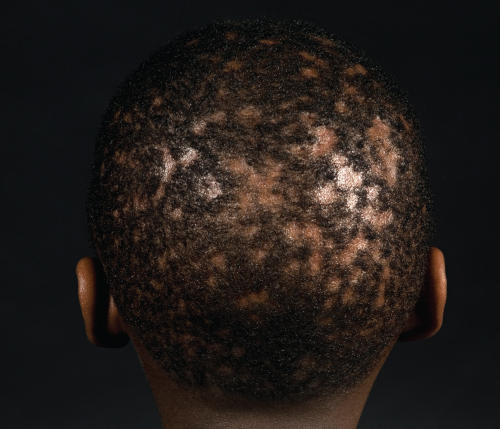

Tinea capitis (scalp ringworm) mainly affects pre-adolescent children. The main fungal pathogens isolated include Trichophyton, Microsporum and Epidermophyton. The most commonly isolated fungus in urban settings is T. tonsurans; it penetrates the hair shaft (endothrix fungus) and is characterised by single or multiple patches of alopecia, often minimal scaling and occasionally inflammation. T. tonsurans must be treated with systemic antifungal therapy to clear the endothrix infection.

Clinically, features are highly variable: diffuse scaling, grey patches, black dots (broken-off hairs), multiple pustules, patchy alopecia (Figure 16.3), extensive alopecia with inflammation (Figure 16.4) kerion formation and occipital lymphadenopathy. A kerion is an inflamed, boggy, pustular lesion on the scalp (Figure 16.5) that occurs when there is a brisk inflammatory response. This settles with systemic antifungal treatment and does not require surgical drainage. The clinical differential diagnosis of tinea capitis includes scalp eczema/psoriasis, folliculitis, alopecia areata and seborrhoeic dermatitis.

Figure 16.3 Patchy alopecia in tinea capitis caused by Trichyophyton tonsurans.

Figure 16.4 Extensive alopecia and inflammation caused by T. tonsurans infection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree