The primary cutaneous fungal pathogens can be separated into two groups: those that tend to cause superficial infections and those that cause deep infections. A third group of cutaneous fungal pathogens are those that usually cause systemic disease and only secondarily involve the skin. The basic pattern of cutaneous infection is relatively uniform within each of these three groups. The degree of inflammatory response to these three categories of fungal infection, however, varies based on a number of factors, particularly host immune status. For example, infections with organisms causing superficial dermatomycoses, such as the dermatophytes, Candida spp., Malassezia (Pityrosporum) furfur, and Cladosporium (Exophiala or Phaeoannellomyces) werneckii, are generally characterized by hyphae or pseudohyphae and sometimes yeast cells in the keratin layer of the epidermis and in follicles. The variable intensity of the tissue reaction in the epidermis and follicular epithelium ranges from almost no response to a very mild focal spongiosis to a more exuberant or chronic spongiotic-psoriasiform pattern. Superficial fungal infections may provoke a superficial lymphocytic or a mixed dermal inflammatory infiltrate. Organisms causing superficial dermatomycosis are not found in the dermis except in the case of follicular rupture.

Deep cutaneous fungal infections typically show a mixed dermal inflammatory cell infiltrate that is often associated with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and occasionally with dermal fibrosis. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis, chromomycosis, phaeohyphomycosis, eumycetoma, rhinosporidiosis, and lobomycosis are examples of fungi that infect the deeper cutaneous tissues.

Incidental cutaneous infections by fungi that usually primarily involve other organs, such as blastomycosis or coccidioidomycosis, typically show a pattern similar to that seen with the deep primary cutaneous fungi: a mixed dermal infiltrate with multinucleated giant cells associated with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. However, a few organisms such as Histoplasma and Loboa loboi are more likely to be associated with epidermal thinning than with hyperplasia. Other systemic fungal infections show characteristic tissue reaction patterns. For example, disseminated candidiasis has prominent microabscess formation, cryptococcosis has a gelatinous or granulomatous reaction pattern, and zygomycosis and aspergillosis have a tendency for vascular invasion and infarction.

Multiple special stains highlight certain fungal elements. These techniques can be helpful especially when the overall histologic pattern is suspicious for a fungal infection but fungi are not apparent on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections. The periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) reaction stains fungi red and can be used with diastase (PAS-D), which clears the tissue of glycogen granules that may be mistaken for fungal spores. Fungi stain positively with PAS-D because their walls contain cellulose and chitin, both of which are rich in neutral polysaccharides and diastase resistant. Gomori methenamine silver (GMS) nitrate stains fungi black and is also useful but may be hard to interpret in tissue containing melanin pigment, which also stains black. Giemsa, Gram, silver, Fontana–Masson, mucicarmine, Alcian blue, India ink, and acid-fast stains also highlight various fungal elements in other primary or secondary cutaneous fungal infections.

DERMATOPHYTOSIS

Dermatophytes are a group of molds that invade and consume keratin by generating proteases (4). They originally came from soil, where they lived on keratinaceous debris, but ultimately were picked up by animals and humans to become the pathogens known today (5,6).

Three genera of imperfect fungi constitute the dermatophytes: Epidermophyton, Microsporum, and Trichophyton. More than 40 species exist, although many are not pathogenic to humans. Dermatophytes may be grouped according to their natural habitat as anthropophilic, zoophilic, and geophilic, with primary reservoirs of infection in humans, animals, and soil, respectively (5). Fungi in all three categories may cause human infections. In immunocompetent hosts, the dermatophytes cause only superficial infections of the epidermis, hair, and nails. Epidermophyton spp., as the name suggests, infect mainly the epidermis, although occasionally the nails are involved. Microsporum spp. infect the epidermis and hair, while Trichophyton spp. may infect the epidermis, hair, and nails.

Clinical Summary. Fungal infections of seven anatomical regions are commonly recognized: tinea capitis (including tinea favosa or favus of the scalp), tinea faciei, tinea barbae, tinea corporis (including tinea imbricata), tinea cruris, tinea manus, tinea pedis, and tinea unguium (Table 23-2).

Common Causal Dermatophytes by Anatomic Regions

Clinical Diagnosis | Causal Organisms |

Tinea capitis | T. tonsurans (black dot), T. violaceum (black dot), T. schoenlenii (favus), M. canis |

Tinea faciei | T. verrucosum, T. mentagrophytes, T. rubrum |

Tinea corporis | T. rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, E. floccosum, T. concentricum |

Tinea manus | T. rubrum |

Tinea pedis | T. rubrum, T. mentagrophytes, E. floccosum |

Tinea unguium | T. rubrum, T. mentagrophytes (vesicobullous), E. floccosum |

Tinea capitis is dermatophytosis of the skin and hair of the scalp. Clinically, scale crust and hairs that are broken off either at the level of the scalp or slightly above it are often seen. In the United States, Tricophyton tonsurans is the most common pathogen of this anatomic site. Because T. tonsurans invades the hair shaft (endothrix infection), infection presents as broken-off hairs (black-dot ringworm), which in some patients has an associated marked inflammatory reaction. Favus is a severe tinea capitis usually caused by T. schoenleinii, although a similar clinical picture may occasionally be seen with other fungi. Favus affects mainly the scalp, where it produces inflammation with formation of perifollicular hyperkeratotic crusts called scutula. Destruction of the hair occurs relatively late in the infection, and lesions may heal, with scarring and permanent alopecia. Clinically, both Microsporum canis and M. audouinii show a band of bright green fluorescence in the hair under a Wood light, but because M. canis is zoophilic, it causes a greater inflammatory response than M. audouinii, which is anthropophilic. Trichophyton spp. do not fluoresce in a Wood light except for T. schoenleinii, which shows subtle pale green fluorescence along the length of the hair. A severe inflammatory boggy scalp plaque, called kerion Celsi, may result from infection with zoophilic dermatophytes such as M. canis, and is often accompanied by posterior cervical lymphadenopathy. Tinea faciei is a fungal infection of the glabrous skin of the face characterized by a persistent eruption of red macules, papules, and patches, the latter of which may show an arcuate border. It is caused usually by T. rubrum and occasionally by T. mentagrophytes or T. tonsurans (7).

Tinea barbae is a fungal infection limited to the coarse hair-bearing beard and mustache areas of men. Tinea barbae is usually caused by T. verrucosum (sometimes called cattle ringworm because of its source), but may also be caused by T. mentagrophytes. Both T. mentagrophytes and T. verrucosum are zoophilic and typically cause a kerion-like, boggy, nodular inflammatory infiltration (8).

Tinea corporis is a dermatophytosis of glabrous skin most commonly caused by T. rubrum, followed by M. canis and T. mentagrophytes. In cases caused by T. rubrum, large erythematous patches with central clearing and an arcuate or polycyclic scaly border are seen. Infections with M. canis are more inflammatory, and annular lesions may have a raised papulovesicular borders. T. mentagrophytes typically produces a few annular lesions with little or no central clearing. T. verrucosum may occasionally cause tinea corporis, appearing as grouped follicular pustules referred to as agminate folliculitis (8). The term Majocchi granuloma describes a nodular granulomatous perifolliculitis caused by rupture of an infected follicle, typically of the lower extremity. Majocchi granuloma is commonly caused by T. rubrum and often associated with tinea pedis and/or onychomycosis. Majocchi’s may develop when superficial dermatophyte infections are inappropriately treated with topical steroids, allowing easier spread of the fungal organism down the hair follicle.

Tinea cruris presents as sharply demarcated erythematous patches or thin plaques in the groin, sometimes including the perineal, perianal regions or scrotum. It is usually caused by T. rubrum and occasionally by T. mentagrophytes or Epidermophyton floccosum.

Tinea of the feet and hands (tinea pedis and manuum) are the most common forms of dermatophyte infection and are usually caused by T. rubrum, E. floccosum, or T. mentagrophytes. Tinea pedis may present clinically as interdigital maceration, or plantar (i.e., “moccasin” scale) or vesiculobullous lesions. T. rubrum is anthropophilic and causes relatively noninflammatory scaling on the plantar feet. Infections with T. mentagrophytes tend to cause inflammatory, vesicobullous tinea pedis.

Tinea unguium specifically refers to a dermatophyte infection of the nail, whereas onychomycosis is a nail infection due to any fungi, including dermatophytes, Candida, or a nondermatophyte (9). Up to 90% of mycotic toenail infections and 50% of fingernail infections are caused by dermatophytes, but yeasts (especially Candida albicans) and nondermatophyte molds are also implicated (10). Criteria for diagnosing nondermatophyte onychomycosis have been offered as (a) the presence of hyphae in the infected subungual debris, (b) the persistent failure to culture recognized dermatophytes, and (c) positive cultures of a nondermatophyte (11).

The four clinical types of onychomycosis include distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis (DLSO), superficial white onychomycosis (SWO), proximal subungual onychomycosis (PSO), and Candida infections of the nail. In general, hyperkatosis and onycholysis are common clinical presentations of onychomycosis. DLSO is the most common form found in all patients, including those with HIV, and is caused by dermatophytes, usually T. rubrum (12). SWO is caused primarily by T. mentagrophytes and is more commonly seen in patients with HIV. PSO is typically caused by T. rubrum and is rare in the general population, but can be a presenting sign of HIV. PSO in AIDS is often caused by T. mentagrophytes (13). Candida nail infections present as paronychia, hyperkeratosis, or onycholysis. Nondermatophytes implicated in onychomycosis include Candida spp., Scytalidium (Hendersonula), and Aspergillus (most commonly Aspergillus niger). Fungi thought to be contaminants in nail cultures in all but the immunosuppressed include Cladosporium, Alternaria, Fusarium, Acremonium, and Scopulariopsis (14). There is considerable controversy about the clinical significance of nondermatophyte fungi in nail cultures when a dermatophyte is also identified on culture.

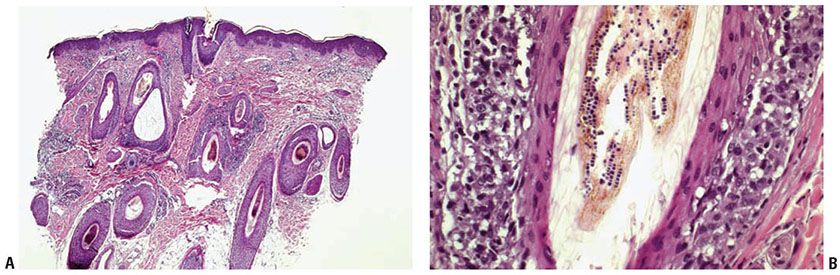

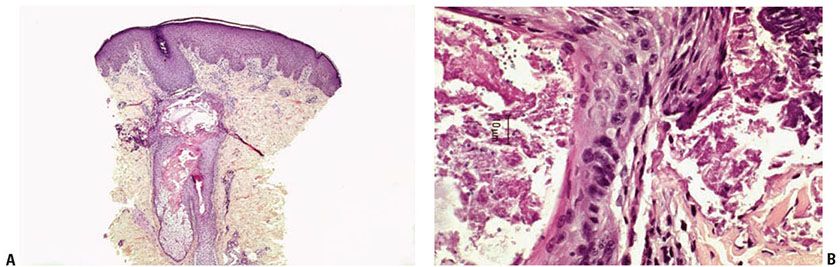

Histopathology. In tinea capitis and tinea barbae, infection of follicles usually starts with colonization of the stratum corneum of the perifollicular epidermis (Fig. 23-1). Hyphae extend down the follicle and invade the hair, penetrating the cuticle first in the subcuticular portion of the cortex, just under the hair surface, and then more deeply in the hair cortex, extending to the upper limit of the zone of keratinization. Rounded and boxlike arthrospores may be found within the hair shaft in endothrix infections (T. tonsurans or violaceum) or penetrating the surface of the hair shaft and forming a sheath around it in ectothrix infections. Although hyphae invade the shafts in both types of infections, they may not be evident in a hair plucked from an endothrix infection because the more superficial hyphae rapidly break up into arthrospores and destroy the keratin of the hair shaft. When plucked, the weakened shaft typically breaks at a relatively superficial point so that only the arthrospores are seen. The dermis, which rarely contains fungi, shows a perifollicular mononuclear cell infiltrate of varying intensity. If there has been follicular disruption, multinucleated giant cells and neutrophils may be present in the dermis. In kerion Celsi, there is a pronounced inflammatory tissue reaction to the zoophilic fungi with follicular pustule formation, interfollicular neutrophilic infiltration, and an intense chronic inflammatory infiltrate surrounding the hair follicles.

Figure 23-1 Tinea capitis. A: H&E stain shows arthrospores and hyphal elements in most follicles. A lymphohistiocytic, perifollicular infiltrate is present. B: H&E stain shows arthrospores in endothrix infection.

In tinea of the glabrous skin, which includes tinea faciei, tinea corporis, tinea cruris, and tinea of the feet and hands, fungi occur only in the horny layers of the epidermis and do not invade hairs and hair follicles. Two exceptions to this are T. rubrum and T. verrucosum, both of which may invade hairs and hair follicles, causing a subsequent perifolliculitis.

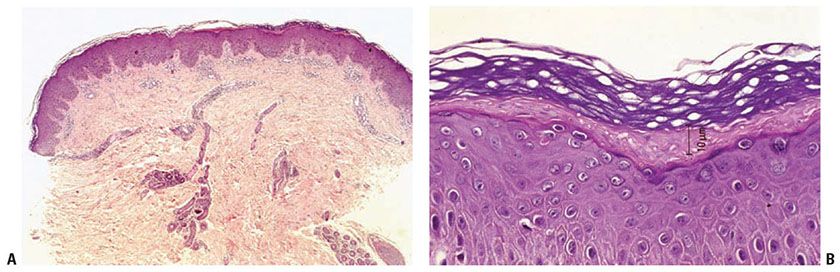

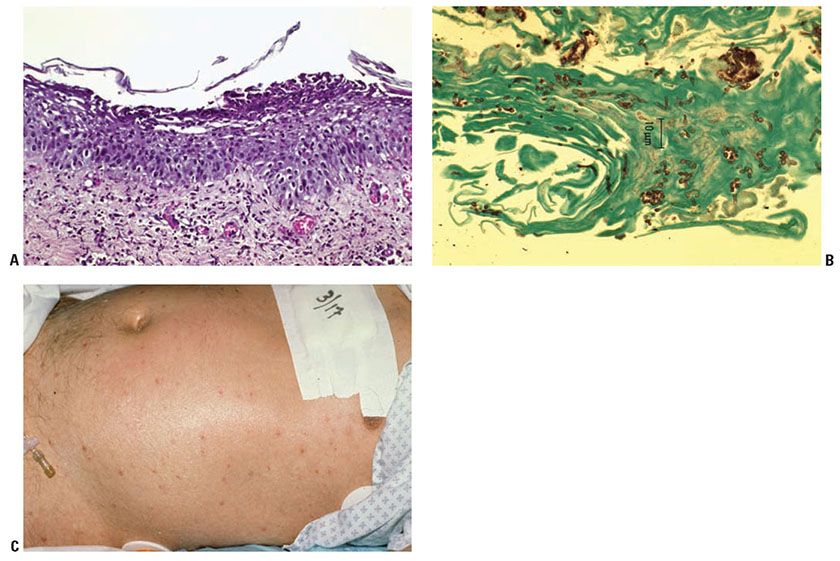

The number of fungi seen in the horny layer varies greatly but may be so small that they may be challenging to find even when treated with the PAS reaction or stained with GMS. Occasionally, they are present in sufficient numbers that they can be recognized as faintly basophilic, refractile structures, even in sections stained with H&E (Fig. 23-2). Their identification in H&E-stained sections may be aided by lowering the microscope condenser, which enhances the refractility of the fungal elements. In infections with Microsporum or Trichophyton, only hyphae are seen, and in infections with E. floccosum, chains of spores are present. If fungi are present in the horny layer, they usually are “sandwiched” between two zones of cornified cells, the upper being orthokeratotic and the lower consisting partially of parakeratotic cells. This “sandwich sign” should prompt the performance of a stain for fungi for verification. The presence of neutrophils in the stratum corneum is another valuable diagnostic clue (15). In the absence of demonstrable fungi, the histologic picture of fungal infections of the glabrous skin is not diagnostic. Depending on the degree of reaction of the skin to the presence of fungi, the histologic features are those of an acute, subacute, or chronic spongiotic dermatitis. (see Chapter 9).

Figure 23-2 Tinea corporis. A: H&E stain shows a superficial perivascular, predominantly lymphoid infiltrate with mild psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia and compact hyperkeratosis. B: Cross sections of refractile hyphae are visible as clear spaces in parakeratotic stratum corneum (H&E stain).

On staining with the PAS reaction or GMS, nodular perifolliculitis, or Majocchi granuloma, caused by T. rubrum shows numerous hyphae and spores within hair follicles and variably in the associated suppurative and granulomatous dermal inflammatory infiltrate. Although the spores present within hairs or hair follicles measure about 2 μm in diameter, those located in the dermis, especially within multinucleated giant cells, may be larger measuring up to 6 μm (16).

The agminate folliculitis caused by T. verrucosum (faviforme) shows hyphae and spores within hairs and hair follicles in PAS-stained sections (10). However, the dermis around the hair follicles contains no fungi. Depending on the severity and stage of the inflammatory reaction, either an acute or a chronic inflammatory infiltrate is predominant around the hair follicles in the dermis. In well-established lesions, the inflammatory infiltrate contains many plasma cells, microabscesses, and small aggregates of foreign body giant cells (8).

In tinea unguium, nail plate biopsy is potentially the method of choice for diagnosis. Although microscopic examination of potassium hydroxide mounts or cultures of nail fragments often establish a diagnosis of onychomycosis, false-negative results may occur due to inadequate sampling, often because the nail bed subungual debris containing fungus has not been sampled. Nail clippings or nail biopsy taken by punch technique or scalpel under local anesthesia will often reveal the fungi on PAS-D–stained sections (17). By far, T. rubrum is the most common causal fungus; occasionally, T. mentagrophytes is present.

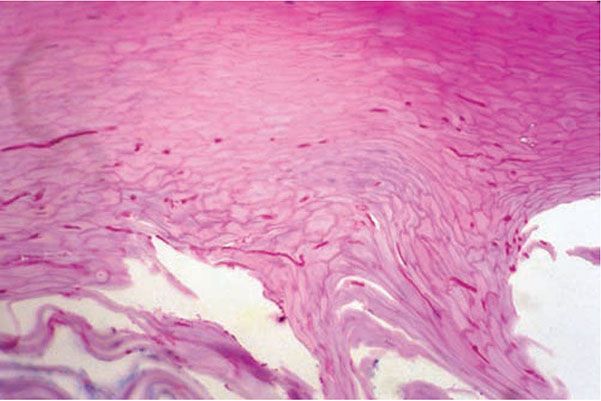

Three histologic patterns are common in nail plate biopsies of onychomycosis (18). In superficial infections, mycelial elements, best visualized with PAS or GMS, are seen in the outer layer of the nail plate. Routine histologic examination of nail plate with PAS staining is a simple, rapid, and sensitive test for fungal elements (19). The second histologic pattern is PAS-D-positive slender, uniform mycelial elements invading the undersurface of the nail plate often occuring in the clinical setting of onycholysis (Fig. 23-3). The third common histologic pattern is seen in Candida infections, where hyphal forms are seen on the undersurface of the nail plate; this will be discussed in a later section (see page 733). Biopsies of nail bed or nail fold epithelium may reveal psoriasiform hyperplasia, spongiosis, and hyperkeratosis, making the identification of fungal elements critical to the correct diagnosis.

Figure 23-3 Tinea unguium. Slender, uniform mycelial elements can be seen within this parakeratotic nail plate (PAS-D stain).

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of DNA from nail plate biopsies has been studied for the diagnosis of onychomycosis but is not routinely used (20). PCR is very sensitive, but ubiquitous contaminant fungi may cause false-positive results, meaning that fungal cultures or histologic confirmation of true hyphal or yeast forms might still be needed.

Pathogenesis. Debate exists regarding factors that predispose individuals to onychomycosis. Trauma is thought to facilitate the entry of fungus into the nail. Epidemiologic data suggests that genetic predisposition plays a role and that the incidence increases with age, but other factors such as humidity, local trauma, and common living/bathing sites have been variably significant predictors (21).

In favus, mainly hyphae and only a few spores of T. schoenleinii are present in the stratum corneum of the epidermis around and within hairs. The scutula (see page 729) consist of compact keratin as well as parakeratotic cells, exudate, and inflammatory cells intermingled with segmented hyphae and spores that are well preserved at the periphery but appear degenerated and granular in the center of the scutula (22). In active areas, the dermis shows a pronounced inflammatory infiltrate containing multinucleated giant cells and many plasma cells in association with degenerating hair follicles. In old areas, there is fibrosis and an absence of pilosebaceous structures.

Principles of Management. Treatment of infections with dermatophytes is guided by the extent of involvement, specifically depth of involvement in the skin and total body surface area affected. Topical therapy is first line for superficial infections of localized areas, typically (scaly macules and/or patches). Onychomycosis typically requires systemic therapy except in cases of SWO or limited nail involvement. In the histologic setting of Majocchi granuloma, oral therapy is typically first line. As always, therapy is individualized based on comorbidities, concomitant medications being taken by the patient, as well as the patient’s willingness to agree to the risks of systemic therapy.

DISEASES CAUSED BY MALASSEZIA FURFUR

Malassezia is a genus of lipophilic yeast that causes two dermatoses: pityriasis versicolor and Malassezia (Pityrosporum) folliculitis (23). The frequently used term tinea versicolor is not accurate, because Malassezia are not dermatophytes.

Clinical Summary. In pityriasis versicolor, multiple round-to-oval pink-to-light-brown patches with fine white scale are seen primarily on the trunk and upper extremities. Gentle scraping of the patches will induce the scale that can be examined for spores and short hyphae. Malassezia (Pityrosporum) folliculitis is a pruritic eruption of 2- to 4-mm acneiform follicular papules and pustules on the trunk and arms of otherwise healthy hosts (24). Potassium hydroxide (KOH) examination of the lesions will reveal only yeast forms.

In addition to these two diseases, Malassezia has been found in lesions of seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, neonatal cephalic pustulosis, and confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud (25,26). Seborrheic dermatitis, for example, has been reported to respond to antifungal therapy and has been associated with heavy colonization by M. furfur. However, these observations and their interpretation are controversial, and it has not been definitively established that M. furfur contributes to the pathogenesis of seborrheic dermatitis (27,28).

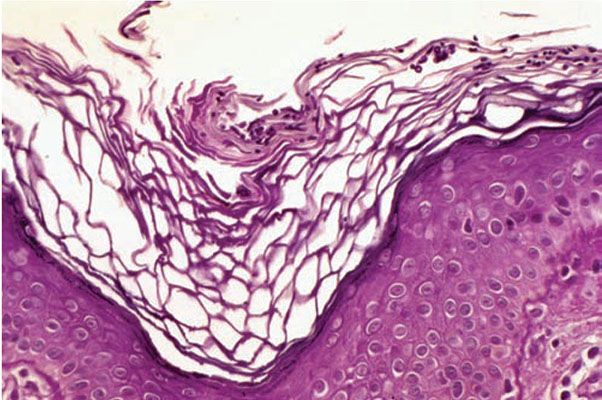

Histopathology. In contrast to other fungal infections of the glabrous skin, the horny layer in lesions of pityriasis (tinea) versicolor contains abundant fungi, which can often be visualized in sections stained with H&E as faintly basophilic structures. Malassezia (Pityrosporum) is present as a combination of both hyphae and spores (Fig. 23-4), the light microscopic appearance of which is often referred to as spaghetti and meatballs. The inflammatory response in pityriasis versicolor is usually minimal, although there may occasionally be slight hyperkeratosis (29), slight spongiosis, or a minimal superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate.

Figure 23-4 Pityriasis (tinea) versicolor. A slightly hyperkeratotic stratum corneum contains numerous hyphae and spores (H&E stain).

Pathogenesis. The names M. furfur, Pityrosporum orbiculare, and P. ovale are often used interchangeably probably because these are identical in culture (30). In vivo, M. furfur becomes dimorphous by forming numerous true septate hyphae in addition to spores. The organism then becomes pathogenic (23).

Several theories exist to explain the characteristic clinical pigmentary alterations in pityriasis versicolor, although none have been convincingly proven. Hypopigmentation may be caused by filtering of ultraviolet light by the organism, a block in melanosome transfer to keratinocytes, or the inhibition of melanin synthesis by azelaic acid or lipoxygenase produced by Malassezia (31). Hyperpigmentation is thought by some to be secondary to inflammation, hyperkeratosis, or greater numbers of organisms in the skin.

Principles of Management. Pityrosporum versicolor is an infection at the level of the cornified layer and therefore easily reached by topical therapy. However, the extensive body surface area often involved means that oral therapy may be preferred. Regardless of the treatment utilitzed, it is important to educate the patient regarding the high risk of recurrence. One frequently utilized method for limiting recurrence is periodic washing with an antifungal shampoo.

Malassezia (Pityrosporum) Folliculitis

The involved pilosebaceous follicles show hyperkeratosis with dilatation resulting from plugging of the infundibulum with keratinous material. Inflammatory cells are present both within and around the follicular infundibulum. In some instances, the follicular epithelium is disrupted with development of a peri-infundibular abscess (32) (Fig. 23-5). PAS-stained sections show PAS-positive, diastase-resistant, spherical to oval, singly budding yeast organisms that are 2 to 4 μm in diameter. They are located predominantly within the infundibulum and at the dilated orifice of the follicular lumen but are occasionally observed also in the perifollicular dermis.

Figure 23-5 Malassezia (Pityrosporum) folliculitis. A: A plugged and ruptured follicle contains numerous round yeast forms (H&E stain). B: H&E staining shows round and budding yeast forms in follicle and surrounding dermis.

Histogenesis. It has been assumed that Malassezia organisms cause hyperkeratosis in the follicular ostium, thereby preventing the normal flow of sebum and causing the follicular, acne-like lesions.

Principles of Management. Treatment of pityrosporum folliculitis generally requires oral therapy with an azole antifungal. The dermal depth of involvement of this infection means topical therapy is less likely to be effective.

CANDIDIASIS

C. albicans is a dimorphous fungus growing in both yeast and filamentous forms on the skin. It exists in a commensal relationship with man.

The spectrum of infection may be divided into four groups: acute mucocutaneous candidiasis, chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC), disseminated candidiasis, and Candida onychomycosis.

Acute Mucocutaneous Candidiasis

Clinical Summary. Acute mucocutaneous candidiasis is the benign, self-limited form of candidiasis and is caused by environmental changes that are local, as in hot, humid conditions, or that are systemic, as in antibiotic or corticosteroid therapy. Clinical variants of acute mucocutaneous candidiasis include erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica, Candida vaginitis, paronychia, Candida intertrigo, and thrush. Intertriginous lesions show erythematous, often-eroded patches and thin plaques often with peripheral erythematous macules and papules, the so-called satellite lesions. Candida infection of the mucous membranes are tender erythematous patches or white plaques that reveal a glistening, erythematous undersurface when scraped.

Candida infection is associated with specific host and environmental factors. Candida is the most common pathogen in patients who have had a solid organ transplant, and candidiasis tends to occur within the first 6 months after transplant. Age (infancy, old age), antibiotic use, malignancy, chemotherapy, endocrinopathies (diabetes, Cushing syndrome), and disorders of immunity, including HIV/AIDS, are risk factors for Candida infection (33,34). More effective treatment of AIDS has led to a decline in the incidence of clinically apparent candidiasis in these patients.

Congenital cutaneous candidiasis is a result of ascending intrauterine infection from vaginal candidiasis. There are widely scattered macules, papulovesicles, and pustules at birth or in a few days thereafter. Neonatal candidiasis, on the other hand, manifests as oral candidiasis or diaper dermatitis after the first week of life and is acquired during passage through the birth canal (35).

Histopathology. Cutaneous and mucous membrane Candida infection show similar features. If the primary lesion is a vesicle or pustule, it is usually subcorneal as in impetigo (Fig. 23-6A, B). In some instances, the pustules have a spongiform appearance, similar to the spongiform pustules of Kogoj seen in pustular psoriasis (see Chapter 7).

Figure 23-6 Candidiasis. A: H&E staining shows a subcorneal pustule with an underlying mixed dermal infiltrate. B: GMS staining shows pseudohyphae and ovoid yeast in hyperkeratotic stratum corneum. C: Erythematous to violaceous papulonodules of disseminated candidiasis in a patient with leukemia.

The fungal organisms are present, usually in small amounts only, in the stratum corneum. They are predominantly pseudohyphae and ovoid spores, with some of the latter in the budding stage. These septate pseudohyphae show branching at a 90-degree angle and measure from 2 to 4 μm in diameter. The pseudohyphae tend to be constricted at their septa and to have septa at their branch points (36). The ovoid spores vary from 3 to 6 μm in size (Table 23-3).

Pathogenesis. By electron microscopy, the majority of the mycelia and spores are situated inside the cells of the stratum corneum, many of which are parakeratotic (37).

Principles of Management. Treatment of acute mucocutaneous candidiasis involves topical therapy with nystatin, or treatment with topical or oral azole antifungal therapy. Attention should also be directed at minimizing factors that predispose the patient to recurrent infection. Patients who have recurrent disease may benefit from maintenance, preventative therapy.

Chronic Mucocutaneous Candidiasis

Clinical Summary. CMC is a heterogeneous group of conditions in which patients have chronic and recurrent candidal infections of the skin, nails, and mucous membranes. CMC may be inherited as an autosomal dominant or recessive condition. It may also be due to endocrinopathies or immunodeficiency. By definition, systemic involvement does not occur in CMC (38). The individual lesions of CMC are similar clinically and histologically to those seen in acute mucocutaneous candidiasis and must be distinguished by their clinical course (38). The exception is seen in CMC beginning in childhood when a rare clinical variant called Candida granuloma may develop. Candida granuloma presents clinically as numerous hyperkeratotic, crusted plaques on the face and scalp but occasionally elsewhere (39).

Currently, the most common type of CMC is probably seen in patients with AIDS who often have recurrent candidal infections of the mouth and perianal area. Oral candidiasis may occur as an early sign of immunosuppression, before other symptoms have appeared (40), and if persistent may be an indication of esophageal candidiasis (41). In addition, Candida organisms are frequently observed on the surface of lesions of oral hairy leukoplakia, which is a viral leukoplakia caused by Epstein–Barr virus, perhaps in combination with human papillomavirus (see Chapter 25).

Histopathology. The histologic findings are identical with those of acute mucocutaneous candidiasis, except in cases of candidal granuloma. Candidal granuloma shows pronounced epidermal papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis and a dense infiltrate in the dermis composed of lymphoid cells, neutrophils, plasma cells, and multinucleated giant cells. The infiltrate may extend into the subcutis. C. albicans usually is present only in the stratum corneum (39). In some instances, however, fungal elements are found also within hairs, viable epidermis, and dermis.

Principles of Management. The heterogeneous nature of immunodeficiencies in patients with CMC has in common the inability of their cellular immunity to manage Candida. Therefore, medical management directed toward eradication of the infection, typically with a triazole antifungal such as fluconazole, must be followed by systemic maintenance therapy.

Disseminated Candidiasis

Clinical Summary. Candida is the fourth leading cause of hospital-acquired bloodstream infection in the United States, but cutaneous involvement is only seen in 13% of cases (42). It primarily affects those with impaired host-defense mechanisms, particularly those with hematologic malignancies. C. albicans accounts for just over half of the cases of Candida fungemia, and Candida glabrata ranks number two, with incidence of the latter increasing directly with age (42,43). Cutaneous lesions of disseminated candidiasis are erythematous or violaceous papulonodules with central clearing that measure 0.5 to 1.0 cm in diameter (Fig. 23-6C). The triad of fever, rash, and diffuse muscle tenderness in an immunocompromised host is presumptive for disseminated candidiasis. However, the clinical diagnosis may be delayed, as patients often present with nonspecific symptoms and current methods for diagnosing candidemia rely on blood cultures that require several days. In addition, the speciation of Candida by culture is problematic given that all yeast cultures that form germ tubes and chlamydospores are by generalization designated C. albicans in many labs (44). Thus, a skin biopsy may be critical to the early diagnosis of disseminated candidiasis. Because the diffuse muscle tenderness is caused by infiltration of muscle tissue by yeast organisms, biopsy of a tender muscle may also aid in establishing the diagnosis of disseminated candidiasis (45).

Histopathology. Histologic examination reveals one or several aggregates of hyphae and spores focally within the dermis, often at sites of vascular damage and generally visible only in sections stained with the PAS reaction or GMS. Some of the spores, which are 3 to 6 μm in diameter, show budding. The aggregates of hyphae and spores may lie in an area of leukocytoclastic vasculitis (46), within a microabscess (44), or in an area of only mild inflammation. The aggregates of Candida often are small, and step sections through the biopsy specimen may be necessary to find them. The epidermis is usually unaffected.

Principles of Management. Candidemia, particularly in the neutropic patient, is a life-threatening infection with risks of multiorgan failure and death. Treatment is a medical emergency requiring prompt systemic antifungal therapy and supportive measures. Certain species of Candida may exhibit resistance to standard first-line systemic antifungal agents and may require alternative agents; consultation with an infectious disease specialist is suggested to determine appropriate therapy and duration of treatment.

Candida Onychomycosis

Clinical Summary. Candida onychomycosis is a form of nail infection characterized by separation of the nail plate from the nail bed. Paronychia and loss of the proximal nail fold are not uncommon in Candida infections of the nail unit.

Histopathology. Candida commonly causes onycholysis but distinguishes itself histologically from the dermatophytes by its lack of nail plate invasion (18). Yeast forms may be seen along the undersurface of the nail plate. Candida may mimic the psoriasiform changes and inflammatory response of onychomycosis caused by dermatophytes. Candida spp. occur as ovoid yeasts that measure 3 to 6 μm in diameter and as pseudohyphae that measure 2 to 4 μm in diameter. These pseudohyphae may appear thick and bulbous and have an irregular caliber compared with the smooth, thin, and regular hyphae of dermatophytes.

Principles of Management. Treatment of Candida onychomycosis is difficult, and consideration of treatment relies on an accurate diagnosis. In general, the diagnosis of onychomycosis by nondermatophytes requires nail culture of the same nondermatophyte at two separate periods in time, lack of dermatophyte on culture, and visualization of fungus affecting the nail plate either by potassium hydroxide (KOH) or by light microscopy after PAS-D stain. The diagnosis should be certain before consideration of treatment with an oral azole antifungal is considered, particularly since contaminant yeast and molds are not uncommon in nail plate cultures, systemic antifungal medications have potentially serious side effects and the risk of recurrent nail infection is significant. As an alternative or adjunct to medical therapy, if the nail is thickened and problematic, it may be chemically and/or manually thinned.

ASPERGILLOSIS

Aspergillus spp. are ubiquitous in the environment. Humans are constantly exposed to and frequently colonized by these organisms, although they rarely cause disease.

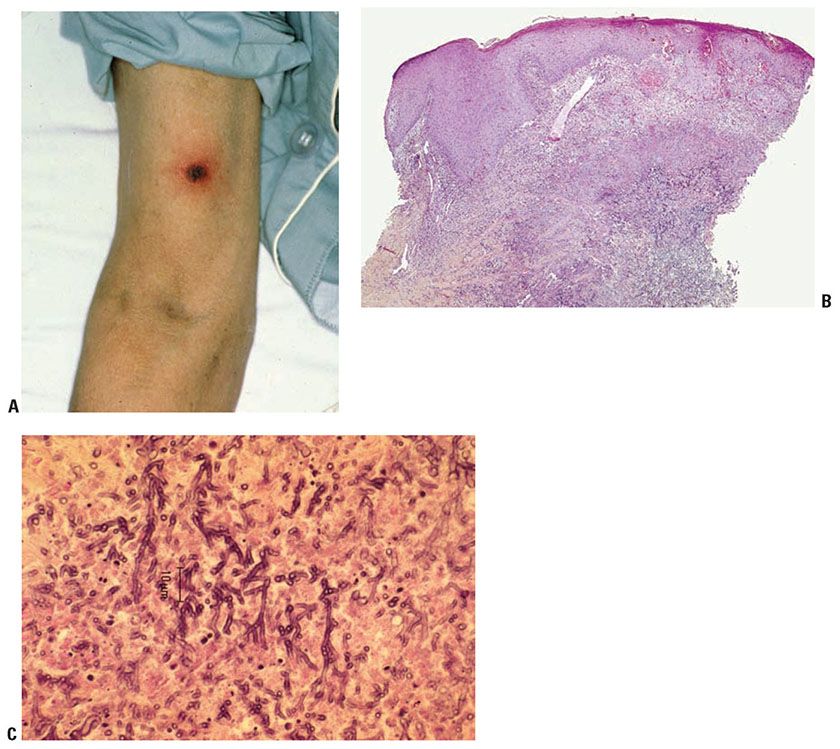

Clinical Summary. Severe, invasive aspergillosis typically involves the lungs and is usually seen only in immunocompromised hosts, particularly those with neutropenia, hematologic malignancy, or a history of chronic corticosteroid or antibiotic therapy (47,47a). Indeed, in neutropenic patients with hematologic malignancy, Aspergillus infection has overtaken candidal infections as the most frequent fungal infection in some populations. Aspergillus fumigatus is the most common cause of both colonization and invasive aspergillosis, followed in frequency by A. flavus and A. niger (48). Cutaneous aspergillosis may occur as a primary infection or may be secondary to disseminated aspergillosis (Table 23-4). The lesions of primary cutaneous aspergillosis are usually found at an intravenous infusion site: either at the actual access site (49) or where the unit has been secured with a colonized board or tape (50). There may be one or more macules, papules, plaques, or hemorrhagic bullae that may rapidly progress into necrotic ulcers with a heavy black surface eschar (Fig. 23-7A). In immunocompromised patients, dissemination may follow and is often fatal if untreated with amphotericin B, itraconazole, or newer antifungals such as caspofungin (47). In addition, Aspergillus may colonize burn or surgical wounds and subsequently invade viable tissue. Patients with AIDS may develop primary cutaneous infection, but dissemination is not typical unless they have one or more of the previously mentioned risk factors (51). Umbilicated papules clinically resembling lesions of molluscum contagiosum, and representing “dermatophyte-like” involvement of follicles, have been described in AIDS-related cases (50). Secondary cutaneous aspergillosis, usually associated with invasive lung disease, shows multiple scattered lesions as a result of embolic hematogenous spread and has a poor prognosis (47,52). Disseminated aspergillosis often manifests as angulated purpura with central areas of dusky necrosis, generally distally due to hematogenous spread.

Figure 23-7 Aspergillosis. A: Necrotic ulcerated plaque in a leukemic patient with cutaneous Aspergillus. B: H&E staining shows a central area of dermal necrosis with branching hyphae. C: H&E staining shows septate hyphae branching at an acute angle in a background of necrotic tissue.

Histopathology. Unlike most deep cutaneous fungal infections, pseudoepitheliomatous epidermal hyperplasia is not characteristic of cutaneous aspergillosis. In the more serious primary forms and in the secondary disseminated form, numerous Aspergillus hyphae are seen in the dermis (Fig. 23-7B, C). Hyphae may be seen in H&E-stained sections, but PAS or silver methenamine staining may be required. The hyphae, which measure 2 to 4 μm in diameter (47), are often arranged in a radiate fashion, are septate, and show branching at an acute angle. Spores are absent. Hyphae may be seen invading blood vessels (47) and may be seen around areas of ischemic necrosis with variable amounts of mixed inflammation.

In patients with primary cutaneous or subcutaneous aspergillosis who are otherwise in good health, the number of hyphae present is relatively small and there is an associated granulomatous reaction.

Principles of Management. Treatment of secondary cutaneous aspergillus is a medical emergency and requires systemic antifungal therapy, debridement as necessary and supportive measures. Primary cutaneous aspergillus requires systemic antifungal therapy and often debridement of necrotic tissue.

ZYGOMYCOSIS (MUCORMYCOSIS, PHYCOMYCOSIS)

Zygomycosis describes infections by ubiquitous molds of two orders: Mucorales and Entomophthorales. The term mucormycoses describes infection with Rhizopus or Mucor, the two medically significant genera of the order Mucorales (53).

Clinical Summary. Zygomycotic infections are aggressive and often occur in ketotic diabetics, but infections may also be seen in other settings such as burns, iatrogenic immunosuppression, chronic renal failure, hematopoietic malignancy, and AIDS (54,47a). Widespread use of voriconazole prophylaxis in patients with hematopoietic malignancy may be contributing to increased incidence of zygomycotic infections in that population. Entomophthoraceae may cause chronic cutaneous and subcutaneous infections in otherwise healthy hosts.

Cutaneous zygomycosis occurs by implantation of fungi or by hematogenous dissemination. Three main forms exist: rhinocerebral, primary cutaneous, and chronic subcutaneous zygomycosis.

Rhinocerebral zygomycosis is a fulminant infection of the paranasal sinuses that quickly spreads to contiguous structures such as the skin, nose, orbit, and brain (53). Clinical findings include nasal discharge, swelling, mucocutaneous ulceration, and eschar formation.

Primary cutaneous zygomycosis may occur following burns, major trauma or following minor trauma in immunosuppressed patients or those with diabetes (53). It has also been reported after the use of infected tape (55,56). Individual lesions occur early as pustules or blisters that soon ulcerate and form eschars. Depending on the host status, the ulcers either heal or lead to fatal systemic spread. These molds may cause acute, rapidly developing, often lethal infections of immunocompromised patients. Cutaneous lesions may also be seen as a result of embolization and infarction in patients with systemic zygomycosis. The lesions may begin as erythematous macules or nodules that blister and ulcerate (57). A “bull’s-eye” lesion of progressive rings of advancing necrotic tissue rimmed by violaecous erythema has been described (57a).

Chronic subcutaneous zygomycosis occurs in tropical and subtropical areas in otherwise healthy people. Lesions most commonly occur on the face and are slowly enlarging, painless, firm swellings in the dermis (53).

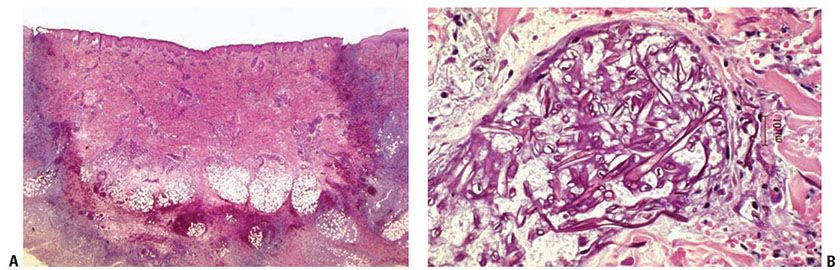

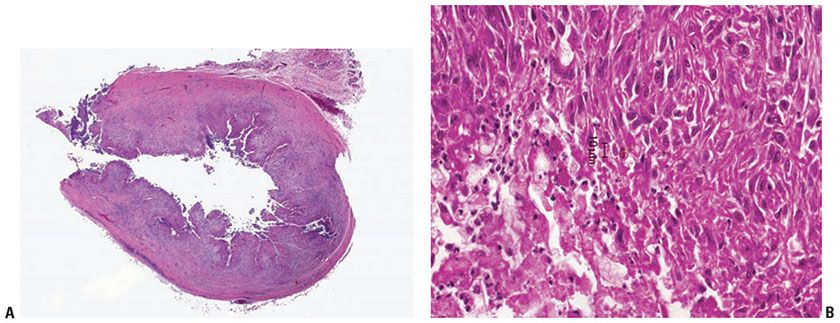

Histopathology. The histologic changes in zygomycosis are primarily dermal. The hallmark of zygomycosis is vascular invasion by very large, long, nonseptate ribbon-like hyphae with thrombosis and infarction (53,57) (Fig. 23-8A). Hyphae branch at 90-degree angles and may also be found in the surrounding tissue (58). The hyphae are thin walled, so they may be twisted or collapsed and often appear ring shaped or oval in cross- or tangential sections (53) (Fig. 23-8B). They are often easily located even in routinely stained sections because of their very large size, up to 30 μm in diameter, although they may be better visualized in PAS- or GMS-stained sections.

Figure 23-8 Zygomycosis (mucormycosis). A: H&E staining shows infarction of dermis, epidermis, and subcutaneous fat with lymphohistiocytic and neutrophilic infiltrate as well as angioinvasion by broad nonseptate hyphae. B: H&E staining shows irregularly branching, twisted, and collapsed hyphae.

Principles of Management. Treatment of Zygomycosis requires surgical debridement, systemic antifungal therapy, often with high dose amphotericin B, and sometimes combination systemic antifungal agents, along with minimization of predisposing factors.

SUBCUTANEOUS PHAEOHYPHOMYCOSIS

Phaeohyphomycosis is a subcutaneous or systemic infection caused by dematiaceous, mycelia-forming fungi (59). This is a histopathologic definition of a disease process that can be caused by many different organisms and can have multiple different clinical presentations. Bipolaris, Phialophora, Alternaria, and Exophiala are fungi responsible for phaeohyphomycosis (60,61). Phaeohyphomycosis has been labeled a “chromic mycosis” in the past but is distinct from chromomycosis, which is characterized by pigmented spores without hyphal forms. In the interest of completeness, it is worth mentioning that eumycetoma is a clinical term that describes chronic subcutaneous infection by fungi, including dematiaceous fungi, ultimately resulting in destruction of adjacent soft tissue and other anatomic structures (62).

Clinical Summary. Phaeohyphomycetes often infect people who are not overtly immunosuppressed. However, immunosuppression does increase the risk of infection with less commonly pathogenic phaeohyphomycetes such as Alternaria infectoria and increases the risk for disseminated disease (47a,63,64).

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis typically presents as a solitary abscess or nodule on the extremity of an adult male. A history of trauma or a splinter can sometimes be elicited. The other major clinical forms of phaeohyphomycosis are infection of the paranasal sinuses and central nervous system.

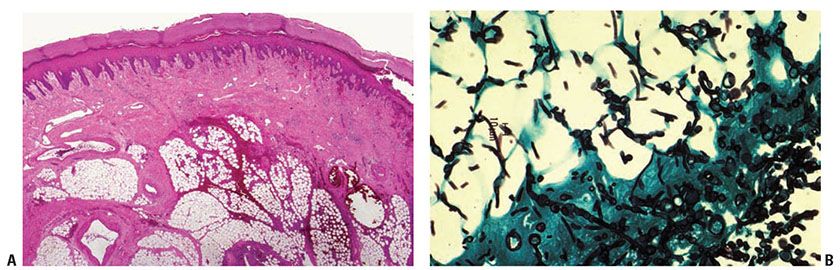

Histopathology. Lesions of subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis start as small, often stellate foci of suppurative granulomatous inflammation. The area of inflammation gradually enlarges and usually forms a single large cavity of pus, with an associated granulomatous reaction and a surrounding fibrous capsule, the so-called phaeohyphomycotic cyst (65) (Fig. 23-9A). The organisms are found within the cavity and at its edge, often within histiocytes (Fig. 23-9B). The hyphae often have irregularly placed branches and show constrictions around their septae that may cause them to resemble pseudohyphae or yeast forms, but true yeast forms are rare. Mycelia, if present, are more loosely arranged than the compact masses of hyphae seen in eumycetoma. Pigment is not always obvious and may be highlighted using the Fontana–Masson stain (60). Diligent search may identify an associated splinter.

Figure 23-9 Phaeohyphomycosis. A: H&E staining shows a pseudocyst with a large central cavity and a fibrous capsule. B: H&E staining shows pigmented hyphal forms at edge of cavity.

Pathogenesis. The subcutaneous cystic type of phaeohyphomycosis is usually caused by Phialophora gougerotii (formerly called Sporotrichum gougerotii) (66). Less commonly, it is due to Exophiala (Fonsecaea, Wangiella) dermatitidis (67). Melanin is directly involved in the virulence of phaeohyphomycetes. Melanin is able to scavenge free radicals used by phagocytic cells to kill fungi, and melanin may also bind the hydrolytic enzymes used by phagocytic cells to lyse fungal cell membranes. Strains of these fungi that lack pigment demonstrate reduced virulence in mouse models (68,69). Nondematiaceous strains have decreased resistance to fungicidal effects of the phagolysosome (70). These factors may also help to explain the virulence of phaeohyphomycetes in immunocompetent patients.

Differential Diagnosis. The organisms of phaeohyphomycosis can be distinguished from Aspergillus spp. because the latter have hyphae with relatively uniform diameter and regular dichotomous branching (71). Furthermore, disseminated aspergillosis is associated with vascular invasion, ischemic necrosis, and relatively less inflammation.

Principles of Management. Surgical debridement is necessary for the eradication of most infections with phaeohyphomycoses. In addition to surgical debridement, management includes systemic antifungal therapy with an azole such as posaconazole, and in life-threatening infections, amphotericin B.

CUTANEOUS ALTERNARIOSIS

Because the hyphae of Alternaria spp. are pigmented, alternariosis may also be considered a phaeohyphomycosis.

Clinical Summary. Alternaria spp. commonly colonize human skin (72) but are generally nonpathogenic for humans. Cutaneous alternariosis may occur following trauma (73); by colonization of a preexisting lesion (74); or rarely by hematologic spread, most commonly from pulmonary infection caused by inhalation of the organism. Patients with cutaneous alternariosis are often debilitated, immunocompromised, or receiving immunosuppressive therapy (47a,71,75). Despite the increasing prevalence of HIV infection, however, the disease is rare in patients with AIDS. Morphologically, the lesions of cutaneous alternariosis are so variable as to be nonspecific and include crusted ulcers, verrucous or granulomatous and multilocular lesions (74), and subcutaneous nodules (73).

Histopathology. Although fungi are found mainly in the deeper layers of the dermis and in the subcutaneous region in the hematogenous and the traumatogenic forms, they are localized predominantly in the epidermis in cases in which Alternaria colonizes preexisting lesions (74). The dermis shows a suppurative granulomatous reaction associated with variable pseudoepitheliomatous epidermal hyperplasia and ulceration. Organisms may be present both as broad, branching, brown septate hyphae, 5 to 7 μm thick (62) (Fig. 23-10), and as large, round-to-oval, often doubly contoured spores measuring 3 to 10 μm in diameter (74). The spores may be seen both lying free in the tissue (72) and within macrophages and giant cells (76). There may be intraepidermal microabscesses with hyphae in the stratum corneum and stratum spinosum (72). The hyphae and spores stain deeply with PAS or silver methenamine.

Figure 23-10 Alternariosis. A: H&E staining shows a mixed inflammatory infiltrate in the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat. B: GMS staining shows broad, branching hyphae.

Principles of Management. Management typically includes surgical debridement and medical management with an azole such as itraconaozle.

NORTH AMERICAN BLASTOMYCOSIS

Clinical Summary. North American blastomycosis, caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, occurs in three forms: primary cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis, pulmonary blastomycosis, and systemic blastomycosis (77).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree