Free TRAM

Jennifer A. Klok

Toni Zhong

DEFINITION

The free transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap is composed of lower abdominal skin, subcutaneous fat, anterior rectus fascia, and a segment of the rectus abdominis muscle. The pedicle for this flap is the deep inferior epigastric artery (DIEA).

The variations in free abdominal flaps based off the DIEA have been classified according to the inclusion and width of the rectus abdominis muscle used. The muscle-sparing (MS) free TRAM flaps spare either the lateral muscle (MS-1) or the medial and lateral muscle segments (MS-2). At either extreme are the free TRAM flap (MS-0), which includes the entire width and partial length of the muscle, and the MS-3 or deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flap, which preserves the entire muscle.1

For the purposes of this chapter, the free TRAM (MS-0) flap will be discussed. This flap was first described by Holstrom in 1979.2

The free TRAM flap has typically been used for the purpose of breast reconstruction. However, other uses include chest wall, upper extremity, lower extremity, and head and neck reconstruction.

ANATOMY

The rectus muscle has a dual blood supply that coalesces in choke vessels at the umbilicus where the deep superior epigastric and deep inferior epigastric systems meet.3

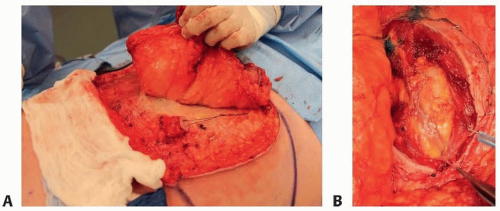

The free TRAM flap is based off the deep inferior epigastric vessels. The pedicle originates from the external iliac artery and then travels cephalad to enter the lateral and deep surface of the rectus abdominis muscle a few centimeters below the arcuate line. Just above the level of the arcuate line, the vessels typically divide into a medial and lateral row and continue superiorly, sending perforating branches through the muscle to supply the overlying skin and fat (FIG 1A,B).3,4

Three variations in DIEA branching patterns have been described, the type II variation with medial and lateral row branching being the most common at 57% to 84%. Type I vessels continue cephalad with the muscle as a single artery (27% to 29%), whereas type III vessels divide into three branches and are least common (14% to 16%).3,4,5

On average, five to six perforators originate from the DIEA.4 In a free TRAM flap, all or most of these perforators are preserved.

The nerve supply to the rectus abdominis muscle originates from the lower six thoracic intercostal nerves. The nerves travel in the fascia of the transversus abdominis muscle and enter posteriorly at the junction between the lateral and middle third of the muscle.3

Functionally, the rectus abdominis muscle acts to flex the torso, originating at the pubic symphysis and inserting onto the fifth to seventh rib cartilages.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Discussing patient goals and expectations for breast reconstruction is one of the most important aspects of the initial consultation for surgery.

It is essential to conduct a thorough review of past medical history, surgical history, medications, allergies, smoking history, personal or family history of clotting disorders, and detailed breast cancer history.

Of particular importance on surgical history are number and type of abdominal surgeries to assess adequacy of the donor site.

It is important to understand the details of the patient’s breast cancer history. All neoadjuvant and expected adjuvant therapies need to be discussed and documented.

If the patient is expected to have postoperative radiation, it is still our typical practice to delay autologous reconstruction until 12 months after completion of radiation.

Tamoxifen is stopped for 2 weeks prior to and after surgery.

Any questionable clotting disorder history warrants consultation with a hematologist.

We will not operate on patients who are smokers. They are required to quit smoking a minimum of 6 weeks prior to surgery. This includes being off nicotine patches. Nicotine urine tests are performed on recent ex-smokers.

On physical exam, assess the patient’s overall body habitus, BMI, and brassiere cup size.

Examine breasts for scars, skin quality (including radiation changes), palpable masses, symmetry, ptosis, and perform standard breast measurements.

Examine abdomen for scars, skin quality, and amount of excess skin and subcutaneous tissue (pinch test), and palpate for hernias.

IMAGING

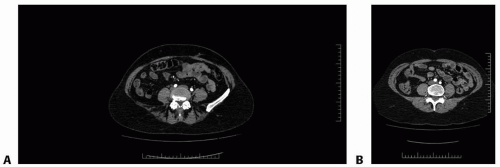

At our center, all patients have computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the abdomen prior to their surgery.

The CTA assists with surgical planning in identification of dominant perforators as well as their intramuscular course from the pedicle.5,6

Having this preoperative understanding of the vessel anatomy for each individual patient can help to guide the decision between doing an MS-3 perforator flap (FIG 2A), which is our preference, and flap that includes muscle to incorporate additional perforators (FIG 2B).

Alternative imaging techniques include color Doppler (duplex) ultrasound, handheld Doppler, and magnetic resonance angiography.6

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Broad indications for choosing autologous reconstruction over implant-based reconstruction include the following: patient goals and expectations, adequate donor site tissue, longevity of reconstruction, resistance to undergo multiple future surgeries, amount of ptosis of the contralateral native breast, importance that the patient places on natural look and feel of the reconstruction, and history of chest or breast radiation.7

Although we perform free TRAM flaps, we aim for DIEP and MS-TRAM flaps in the majority of our breast reconstructions. Sometimes, a full free TRAM is needed; however, this is rarely the case. Maximum preservation of rectus fascia and muscle whenever possible to limit abdominal morbidity should be the goal in reconstruction.

Indications for choosing a full free TRAM over a MS-TRAM or DIEP flap are few but relate to a need for increased flap perfusion and can be divided into patient and intraoperative factors.1

Patient factors include recent history of smoking, prior abdominal liposuction, abdominoplasty or multiple abdominal surgeries with extensive scarring in the rectus abdominis muscle, and large flap volume (greater than 1000 g) required in patients with aforementioned risk factors.1,8,9,10

Intraoperative factors include the number and size of perforators located during flap elevation. The presence of a dominant perforator at least 1.5 mm in diameter would indicate suitability for a perforator flap. If no single dominant perforator is located or the reliability of selected perforator(s) for supply of the flap becomes questionable after temporary occlusion of other identified perforators, then an MS-TRAM or free TRAM is indicated.1

If the medial and lateral row perforators are found to be so widely separated that they come off the extreme edges of the muscle and are so small in caliber to the extent that at MS-TRAM off one row would be inadequate, then the whole width of the muscle would need to be harvested in a full TRAM.

An additional intraoperative scenario that might steer the surgeon to convert to a free TRAM includes encountering a severely scarred or attenuated rectus abdominis muscle where the musculocutaneous perforators are encased in scar and unidentifiable.

Preoperative Planning

Optimize the patient for surgery with appropriate consultations to anesthesia, medicine, and/or hematology as needed.

Carefully review the CTA to understand the size, location, and intramuscular course of the perforators.

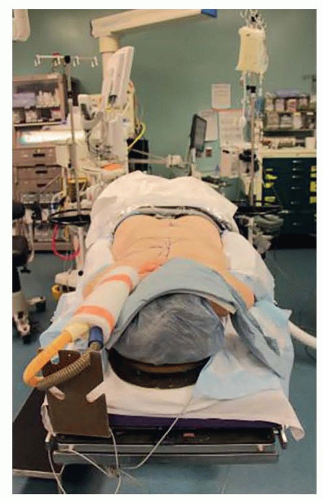

FIG 3 • Demonstrates positioning of the patient. The bed is turned 180 degrees so that the anesthetic machine is at the foot of the bed. The patient’s arms are tucked, the face is protected, and all bony prominences are well padded.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access