Fasciocutaneous Debulking of Extremity Lymphedema: The Charles Procedure

Clifford C. Sheckter

Peter Johannet

DEFINITION

Lymphedema is the accumulation of interstitial fluid and fibroadiposity in subcutaneous tissues as a result of dysfunction in the lymphatic system.

Compared with generalized edema, lymphedema by definition is caused by poor lymphatic outflow (compared to increased capillary leak).1

The disease is generally described in terms of primary vs secondary (ie, acquired) causes.1

Primary lymphedema: congenital (less than 2 years), praecox (first to third decade of life), and tarda (greater than fourth decade of life).

Secondary lymphedema: malignancy, iatrogenic/surgery (most common in developed world), obesity, trauma, and infection/filariasis (most common worldwide).

Although nonoperative treatment is the mainstay, each case should be evaluated individually. Surgical options including radical excision can offer significant improvement.

ANATOMY

Lymphedema can occur anywhere in the body where lymphatics are present; however, the disease tends to be most problematic within the extremities and genitals.

In the extremities, the lymphatic system courses within the soft tissue between the dermis and muscle fascia, and thus, the disease is confined to this area. Anatomic knowledge of the subcutaneous tissues and its contents is crucial for surgical treatment given many nerves run within or adjacent to muscle fascia.

Lower extremity considerations:

Common peroneal nerve at fibular head

Sural nerve at posterior calf

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Generalized edema due to any underlying medical disorder (heart failure, renal failure, cirrhosis) or medication should be ruled out, given these causes are often reversible with proper medical management.

Other limb-enlarging disorders should be considered including chronic venous insufficiency, deep venous thrombosis, congenital musculoskeletal limb discrepancy disorders, myxedema, and neoplasia.

For lymphedema, determine primary vs secondary lymphedema based on the timing of onset, travel history (endemic filariasis), family history, and any personal history of injury, surgery, or radiation.

Two-thirds of cases involve a single extremity; however, bilateral lymphedema is possible depending on the nature of injury (eg, pelvic lymph node dissection).2

Examination of affected limb reveals supple tissue that often “pits” when gently pressed. Long-standing lymphedema causes skin changes including thickening of the dermis and thickening of the epidermis (hyperkeratosis).

The classic Stemmer sign is considered positive when the examiner is unable to pinch the skin on the affected side at the dorsum of second toe or second finger. The unaffected side will easily tent when gently pinched.3

Measuring the affected limb is important both in terms of comparison to the normal side (if present) and assessing for improvement with anticipated therapy.

Volumetric measurements are the standard and can be achieved through either estimated circumference measurements or water displacement testing.

Circumference measurements, while easily accessible, can be plagued by poor interrater reliability.4

Water displacement testing, whereby the affected limb is submerged into large containers, is highly precise, albeit cumbersome. Volume in excess of 200 cc (compared to normal side) is considered diagnostic.4

IMAGING

In general, imaging is not necessary for diagnosis with a convincing history and physical exam. If there is uncertainty in diagnosis, tailored imaging can assist in excluding/confirming lymphedema. For surgical planning, some surgeons advocate for ultrasound to ensure competency of the deep venous systems.

Ultrasound can evaluate for deep venous thrombosis.

Computed tomography can evaluate for masses, lipodystrophy, venous thrombosis, and lymphedema with high sensitivity.

Lymphoscintigraphy can help confirm the diagnosis through demonstrating both quantitative and qualitative impairment in trace.

Indocyanine green lymphangiography can assist in delineating drainage patterns and is more often employed in the preoperative planning of lymphovenous anastomosis or vascularized lymph node transfer.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

There are limited prospective studies comparing the different treatments of lymphedema, particularly surgical approaches. There is no defined period of waiting or algorithm for performing the different procedures.

In general, nonoperative therapy is considered first line,1 largely consisting of concentric extremity compression wrapping with or without mechanical compression. Surgery is usually reserved for those patients with the following characteristics:

Failed compression therapy

Recurrent soft tissue infection and/or cellulitis

Quality of life limitations such as pain, limited mobility, and psychosocial distress

Operations are classified into two categories: physiologic and ablative.

Physiologic procedures involve three techniques

Creating new lymphatic anastomoses (lympholymphatic bypass).

Diverting lymphatic drainage into the venous system (lymphovenous bypass).

Autotransplanting lymph nodes from another part of the body (vascularized lymph node transfer). These techniques have their own chapter for further discussion on technique.

Ablative techniques involve directly removing tissue from the affected extremity and fall into two operations:

Liposuction

Direct excision

Direct excision is further characterized based on reconstruction modality: skin graft vs flap.

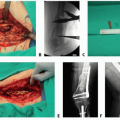

Originally described by Sir Richard Henry Havelock Charles in the early 20th century from his proceedings in India, the surgery attributed to Charles involves radical debridement of all soft tissue superficial to skeletal muscle with placement of skin grafts from the excised tissue onto the limb muscle.5

Staged excision: the lower extremity is excised in at least two operations staged 3 months apart. Thick tissue flaps are elevated 1 to 2 cm in thickness and then underlying soft tissue is excised down to muscle fascia. Flap skin edges are closed in a single dermal layer using permanent suture (eg, 3-0 nylon). This procedure shares eponyms including Homans, Sistrunk, and Thompson procedure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree