11.2 Facelift

Introduction to deep tissue techniques

Synopsis

In its pure form, the subcutaneous, skin-only facelift has a limited effect on the position of heavier deep tissue.

In its pure form, the subcutaneous, skin-only facelift has a limited effect on the position of heavier deep tissue.

In SMAS plication, a skin flap is created with suture manipulation of the superficial fat and the underlying SMAS/platysma.

In SMAS plication, a skin flap is created with suture manipulation of the superficial fat and the underlying SMAS/platysma.

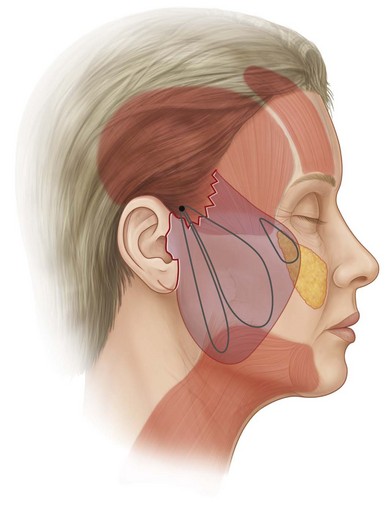

In loop suture techniques (MACS lift), a skin flap is created with long suture loops taking multiple bites of superficial fat and platysma – fixed to a single point on the deep temporal fascia.

In loop suture techniques (MACS lift), a skin flap is created with long suture loops taking multiple bites of superficial fat and platysma – fixed to a single point on the deep temporal fascia.

The supraplatysma plane creates a single flap of skin and superficial fat mobilized and advanced along the same vector.

The supraplatysma plane creates a single flap of skin and superficial fat mobilized and advanced along the same vector.

SMASectomy involves a skin flap plus excision of superficial fat and SMAS from the angle of the mandible to the malar prominence, with direct suture closure of the resulting defect.

SMASectomy involves a skin flap plus excision of superficial fat and SMAS from the angle of the mandible to the malar prominence, with direct suture closure of the resulting defect.

A SMAS flap raised with skin attached (deep plane) creates a flap of SMAS/platysma, superficial fat and skin, all mobilized and advanced along the same vector.

A SMAS flap raised with skin attached (deep plane) creates a flap of SMAS/platysma, superficial fat and skin, all mobilized and advanced along the same vector.

A separate SMAS flap (dual plane) creates two flaps, the skin flap and the superficial fat/SMAS/platysma, which are advanced along two different vectors.

A separate SMAS flap (dual plane) creates two flaps, the skin flap and the superficial fat/SMAS/platysma, which are advanced along two different vectors.

The subperiosteal lift involves dissection against bone, with mobilization and advancement of all soft tissue elements.

The subperiosteal lift involves dissection against bone, with mobilization and advancement of all soft tissue elements.

Introduction

In the previous chapter, the generic subcutaneous “skin-only” facelift was described. However, as reviewed in Chapter 6, the anatomy of facial aging is a complex process involving all layers of the face from the skin through to the bone. Logically, surgical rejuvenation of the aging face should address all or most of these tissue layers. To this end, rejuvenation of the skin is reviewed in Chapter 5. Within the soft tissue of the face, the two principle age-related changes are loss of midface volume and soft tissue descent. (Surgical methods to add volume are described in Chapters 14 and 15.) With regard to soft tissue descent, a host of surgical approaches have been described. In this chapter the standard methods available to elevate and rearrange the deep soft tissues of the face are outlined; in the coming chapters, they will be described in detail by authors who developed these techniques, or by authors who use them routinely. The subcutaneous facelift is included here for comparison purposes, although in its classic form, there is no attempt to address the deeper tissues of the face.

Subcutaneous facelift

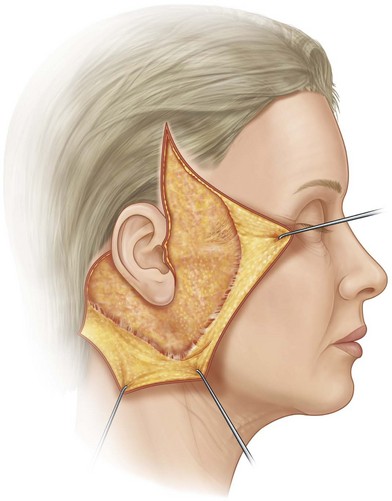

The “skin-only” facelift (Fig. 11.2.1) is used to tighten loose facial skin by advancing a random pattern skin flap and removing the excess. By definition, there is nothing done to the deep facial tissues. A tried and true technique, this method can be effective when the only significant problem is loose skin. For example, some patients with very thin faces and little or no subcutaneous fat may present with loose skin only. It is also useful in secondary or tertiary situations where deep tissues have previously been repositioned and the presenting problem is a recurrence of skin laxity. In that setting, a short scar approach will often suffice. Advantages of the skin-only facelift include its simplicity, a rapid postoperative recovery, and the use of a dissection plane which does not risk damage to the facial nerve or other deep structures. Disadvantages include: a minimal effect on underlying facial shape and the inherent disadvantage that skin is an elastic structure which will stretch when tension is applied. Therefore, the longevity of effect is in question, especially when the skin is used to reposition heavy facial tissues. Unfortunately, if the surgeon increases skin tension in a misguided attempt to reposition ptotic deep tissue, the shape of the face can be distorted. Skin tension will flatten facial shape, negating the rounded contours of youth. Also patients in the facelift age group have usually lost elasticity in their skin and therefore, with tension, are prone to a stretched look with wrinkles re-oriented in abnormal directions. Lastly, excess skin tension at the incision line can cause malposition of the hairline, alopecia, distorted earlobes, widened scars, and the potential for skin flap necrosis.

SMAS plication

After surgeons learned to raise a large random pattern skin flap, it became apparent that facial shape could be changed by using sutures to manipulate the underlying soft tissue.1

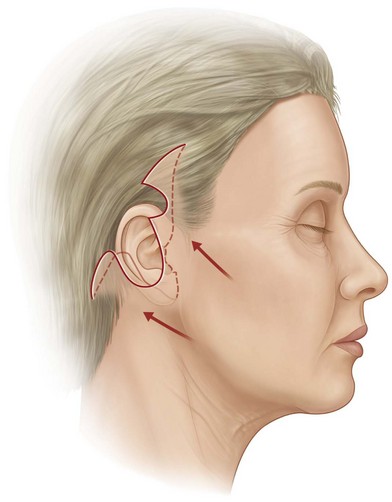

Suture plication creates an infolding of the superficial fat, drawing fat from the lower in the face up to the point where the sutures are placed. Areas of fixed tissue, such as the fixed SMAS (Fig. 11.2.2) over the parotid gland are less movable, and can act as an anchoring point; anterior to the parotid, mobile tissues can be easily manipulated.2 Multiple sutures with customized vectors can be used allowing reshaping of the superficial facial fat. The technique is relatively easy to master; it can be customized for the individual case, and can be modified intraoperatively by removing and replacing sutures as necessary. The superficial fat can be shifted in a different direction than the skin. When plication sutures are placed properly, there is little or no risk to branches of the facial nerve. Proponents of plication claim long-lasting results without the need for invasive and potentially dangerous dissections.3 The primary concern with plication is the potential loss of effect if sutures cut through the soft tissue (the “cheese wire” effect). Another concern is that the degree of improvement may be limited by the tethering effect of the retaining ligaments which in this technique are not released. When the subcutaneous fat is fragile, suture fixation may fail, and plication may have a limited effect in patients with heavy jowls and ptotic tissues in the neck.

Loop sutures (MACS lift)

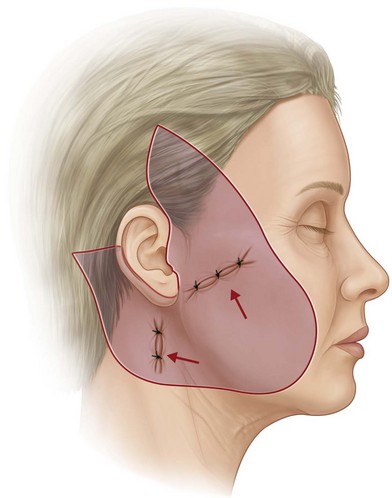

A variation of suture plication is the loop suture method (Fig. 11.2.3), for which the main variant is the MACS lift (minimal access cranial suspension). This procedure, which itself was derived from the “S-lift”, relies on long suture loops which take multiple small bites of soft tissue.4,5 Some of these bites are strategically placed into the SMAS and platysma. The loop sutures are fixated to the deep temporal fascia at a point just superior to the zygomatic arch and anterior to the ear. The theoretical explanation for the efficacy of this technique relates to the use of multiple bites of tissue which the developers of the technique feel creates “microimbrications” of the superficial fat and SMAS.5 Anteriorly, a third suture can be placed to advance the malar fat pad, although the fat pad is not surgically released and its repositioning depends on its own intrinsic mobility. Treatment of the neck usually involves closed liposuction. Proponents of this technique recommend a nearly vertical vector for the skin flap, with a short scar incision. The advantages with this technique are similar to those of plication, although proponents point to the added benefit of using a more firm point of fixation (deep fascia) and the improved effect of micro-imbrications. Disadvantages are the same as SMAS plication: potential loss of effect if the sutures pull through, the lack of ligamentous release and concerns about the effectiveness of sutures holding heavy jowls and ptotic neck tissues against gravity. Lastly, surgeons must address the tendency for loop sutures to cause fat to bunch up, potentially leaving bulges which can be visible through the skin.

Supra-platysmal plane facelift

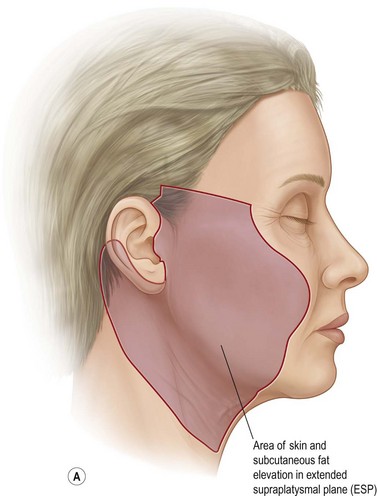

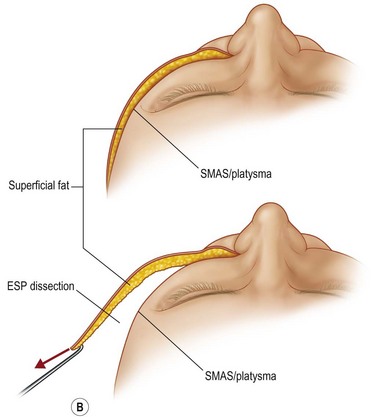

The supra-platysmal plane facelift (Fig. 11.2.4) involves a deep subcutaneous dissection carried out immediately superficial to the SMAS and platysma. Originally described as the extended supra-platysmal (ESP) dissection plane, this procedure raises the superficial fat and skin as a single layer, leaving the SMAS layer untouched. The zygomatic ligaments are released as dissection of the superficial facial fat extends over the malar prominence as far forward as the nasolabial folds. The theory behind this technique is the belief that the superficial fat is a ptotic structure, but the underlying SMAS and platysma are not.6 After the flap has been raised, the fat on the underside of the flap can by contoured and sutures can also be placed from this fat to underlying fixation points. This technique provides good mobilization because ligaments are released, and it produces a thick very robust flap. Also, with no surgical penetration of the underlying SMAS, there is theoretically no risk to branches of the facial nerve. Concerns about this method are that the flap is unidirectional (the skin and fat move en bloc), and the fact that repositioning the weight of this flap depends primarily on skin tension at the suture line.