11.4 Facelift

Facial rejuvenation with loop sutures, the MACS lift and its derivatives

Synopsis

Limit undermining of skin to planned areas for suture loops or for redraping of skin. The indiscriminate delamination of skin of neck structures or in the post-auricular region can unduly influence outcomes. Undermine only as necessary to accomplish the lift, not more.

Limit undermining of skin to planned areas for suture loops or for redraping of skin. The indiscriminate delamination of skin of neck structures or in the post-auricular region can unduly influence outcomes. Undermine only as necessary to accomplish the lift, not more.

Ensure that the neck loop suture has a good bite of platysma fascia. This is important to prevent failure of the neck-lifting component.

Ensure that the neck loop suture has a good bite of platysma fascia. This is important to prevent failure of the neck-lifting component.

Do not make the cheek loop too small. This can result in a wad of tissue that cannot be made smooth.

Do not make the cheek loop too small. This can result in a wad of tissue that cannot be made smooth.

Understand the ability that you have to innovate with the MACS-lift, based on your patient’s individual needs. Too often, we become wedded to a sequence of techniques and ancillary procedures that limits our ability to individualize and adapt for each of your patients.

Understand the ability that you have to innovate with the MACS-lift, based on your patient’s individual needs. Too often, we become wedded to a sequence of techniques and ancillary procedures that limits our ability to individualize and adapt for each of your patients.

The MACS suture loop suspension approach works nicely in secondary or revisionary situations, where there has been earlier deep layer work and repeat deep layer dissections could be both challenging and risky. MACS loop sutures hold well in scar from previous surgery.

The MACS suture loop suspension approach works nicely in secondary or revisionary situations, where there has been earlier deep layer work and repeat deep layer dissections could be both challenging and risky. MACS loop sutures hold well in scar from previous surgery.

Critical evaluation of outcomes is part of the learning process in terms of determining what went right and areas that require improvement. Refinement of technique comes with an honest analysis of the outcome.

Critical evaluation of outcomes is part of the learning process in terms of determining what went right and areas that require improvement. Refinement of technique comes with an honest analysis of the outcome.

Introduction

MACS-lift is an acronym for “minimal access cranial suspension”.1 The first time that I (the author) read the MACS short-scar rhytidectomy paper by Tonnard et al.,2–5 it seemed a puzzling principle which relied on suture loop suspension to a cranial anchoring point, far different that the sheet tightening approach of the classic SMAS-lift that I was performing at the time. It took a trip to the anatomy lab and a visit with Tonnard and Verpaele in Belgium to convince me that there was something different (and possibly better) about the MACS-lift. Once this approach for facial rejuvenation was examined in light of other publications by Labbé,6 Mendelson,7 Besins,8 Pessa/Rohrich,9 and Gardetto,10 there actually appears to be a unifying concept that has scientific and biomechanical validity as a mainstay technique for facial rejuvenation.

Surgical foundation for the MACS-lift

The surgical foundation for facial rejuvenation should address the biomechanical effects of facial aging and volume loss for each patient, depending on their particular needs. Surgeons must be faulted in the past for not having a fundamental understanding of facial aging, volume loss, laminar anatomy, and biomechanical engineering. Our current understanding of the anatomy of facial aging is thoroughly reviewed in Chapter 10, giving insight into the complex biomechanics of facial aging. Aging involves the gravimetric effects on skin and SMAS, loss of elastic property of tissue, volume loss and descent within in fat compartments, and extrinsic effect of sun, genetics, weight loss/gain, and smoking.11–13 Fat within the face does not exist as a confluent mass, but in discreet compartments separated by septae, formerly known as ligaments. Facial anatomy involves a laminar concept in which, movement between layers is possible without surgical delamination. Proponents of ligament release feel that such movement is inadequate for facial rejuvenation, but experience with the MACS-lift provides evidence that sufficient interlayer movement is, indeed possible and surgically effective.

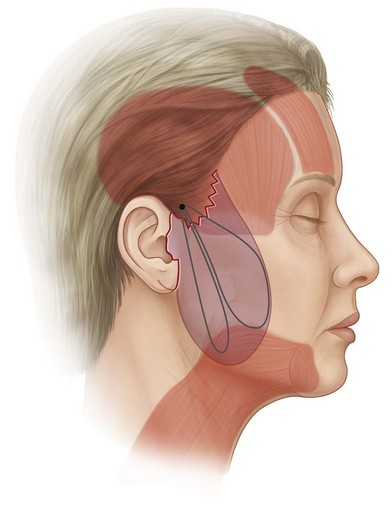

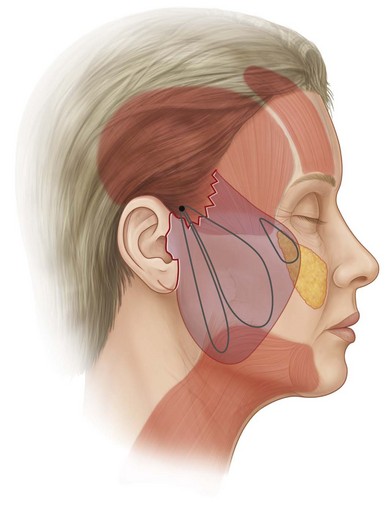

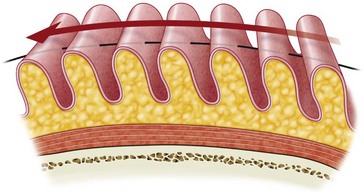

The MACS-lift concept involves the use of suture loops placed in a purse-string fashion in order to elevate deep facial tissue by anchoring to a fixed point. In the basic MACS-lift, there is one anchoring point on the deep temporal fascia, just above the lateral zygoma, and posterior to the passage of the temporal branch of the facial nerve. This is a very robust anchor point that will hold a 0-0 or 2-0 suture without a pull-out failure The “CS” part of the MACS-lift is “cranial suspension”, which refers to the deep temporal fascia’s attachment to the cranium along the temporal crest line. The MACS-lift does not utilize sheet tightening of the SMAS, SMAS plication, or SMASectomy, but relies purely on specialized suture suspension. The basic MACS-lift involves two suture loops, one vertical and one oblique, while the “extended MACS-lift” involves an additional suture to elevate the malar fat to a more anterior anchoring point (Figs 11.4.1, 11.4.2). Suture loops placed within facial tissues results in a gathering and suspension of tissue. Tonnard and Verpaele describe this as “microimbrication” (Fig. 11.4.3).

Fig. 11.4.3 MACS sutures result in a bunching up of soft tissue. This has been termed microimbrication.

How the loops are designed and sequenced is crucial, as once the platysma is pulled upward, it is possible to rotate the layers of the face without a downward traction component of the platysma. By not dissecting skin off the platysma, there is tightening of the neck skin when the platysma is tightened.7 The zone of adherence just anterior to the earlobe, called Lore’s fascia, can be used as a fixed structure to pull against in order to achieve vertical tightening of the platysma as described by Labbé.5

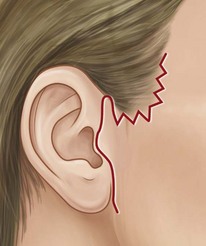

The traditional skin incision for the MACS-lift utilizes a “short scar” anterior hairline approach with no retroauricular dissection. After deep tissue reposition, skin redraping is designed in a purely vertical direction (Fig. 11.4.4).

The amount of skin excision with the vertical approach of the MACS-lift is much less than seen with the classic SMAS-lift. Attention must be paid to a tension-free skin closure in order to promote excellent healing and avoid earlobe distortion. In a divergence of philosophy and practice from Tonnard and Verpaele, patients with greater facial and neck laxity will require extending the incision into the retroauricular area in order to manage lax skin (Fig. 11.4.5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree