11.3 Facelift

Platysma-SMAS plication

Introduction

As summarized in Chapter 11.2, facelifting has evolved appreciably from the simple, skin-only procedures of the early 20th century. Today, we have an almost bewildering array of techniques and tissue planes from which to choose. While each proponent may provide convincing support for their particular technique, most are in agreement about the central role of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS), originally highlighted by Skoog in the 1970s1 and detailed in Mitz and Peyronie’s now classic treatise.2 The question remains precisely what to do with the SMAS in order to balance invasiveness, and thus tissue trauma from which the patient must recover, in addition to potential complications, and its longevity.

The SMAS may be simply elevated and advanced,3 dissected at various planes,4,5 rolled upon itself with mesh to augment malar projection,6 excised,7 or plicated.8 The multiplicity of techniques bears testament to the fact that a universal and standard procedure eludes us still. There is also some evidence that there may be little actual difference, in either the short9 or the long term, between techniques of varying aggressiveness10,11; therefore, procedures with less inherent risk to important structures, such as the facial nerve may be safer. Problems noted include inconsistent results, a less-than-impressive effect on the nasolabial folds and jowls and long operating times, requiring extended periods of careful surgery, particularly with anterior SMAS dissection. Furthermore, the SMAS is relatively avascular,12 behaving more as a graft in certain circumstances, and may be thin and attenuated, thus holding sutures poorly. During revision or secondary surgery, the poverty of vascular supply to the undermined SMAS may present the surgeon with a mass of scar tissue.

Given the recent paradigm shift towards minimally-invasive techniques, to limit facial nerve complications and reduce recovery time, the minimal access cranial suspension (MACS) lift was initially popularly accepted.13 Since its description in 2002, the MACS has proven effective, particularly for younger patients concerned with early jowling, minimal neck ptosis and the desire for minimal downtime. Itself a derivation of Saylan’s ‘S-lift’,14 the MACS lift focussed on the anatomical basis, suture anchoring position and skin excision, but certain limitations have been shown by experience. One of these, the relative lack of malar augmentation was addressed by the addition of a third suture and quickly became commonly applied.15 However, precise purse-string suture placement is not always easy and subcutaneous irregularities may not settle as well as described. Whilst good for younger patients, the authors feel it does not always have a sufficiently strong effect on the lateral neck of older patients, and is painful in the initial postoperative period, with a limitation of mouth-opening, acknowledged by the originators.13 Finally, there are two areas of tissue excess, or dog-ears, in pure vertical-vector lifts, which may fail to settle satisfactorily. The first is infero-posterior to the lobule. The second, cutaneous bunching at the lateral canthus, is particularly pronounced with the powerful suture of the extended MACS15 and may be addressed through a lower lid blepharoplasty incision, however, not all patients require this additional procedure. It has been demonstrated that by utilizing tension in the SMAS rather than the skin, both cutaneous dog-ears and scar stretch3 are minimized.

Experience with these limitations led the authors to the use of sutures to plicate the SMAS; a procedure termed the ‘platysma-SMAS plication’ (PSP) lift. Its advantages (Table 11.3.1) include the application of a postero-superior, as opposed to purely vertical, vector, which allows a lift tailored to each individual. The vertically-extended skin incision permits synchronous temporal lift and reduces sideburn elevation and a visible scar.16,17 While concealing the scar within temporal hair risks alopecia, it allows greater flexibility with no risk of highly visible alopecia between the helical root and hairline. A post-auricular extension, not employed in all cases, is important to ameliorate the post-auricular skin dog-ear, which adds to down-time and has been reported as a problem with the MACS.9

Table 11.3.1 Comparison of chief features for the PSP and MACS facelifts

| PSP | MACS | |

|---|---|---|

| Incision | Vertical temporal (± post-auricular extension) | Inverted L (anterior only) |

| Skin flap | As required | Limited to 5 cm oval |

| Dissection into neck | Yes | No |

| Platysmaplasty | Direct (infralobular excision) | Indirect |

| SMAS fixation | SMAS-SMAS | SMAS-DTF |

| Malar augmentation | Yes | No |

| Vector | Cephaloposterior | Predominantly vertical |

| Skin excision | Tailored, no tension | Tailored, high tension |

| Neck | Multiple procedures | Liposuction in >95% |

| Ancillary procedures | Yes | No |

With no sub-SMAS dissection, PSP is safer, particularly with respect to the facial nerve, and quicker. It is also beneficial where SMAS vascularity is poor. Large bites of SMAS allow greater security, and therefore potential longevity. A second layer of finer imbrication sutures is used, producing both a smooth finish and perhaps additional strength. It is, of course, not without sequelae and does produce two dog-ears in the subcutaneous layer. Fortunately, the first, overlying the malar prominence, has the effect of auto-augmentation and assists with the overall rejuvenation by reversion of the aged “square” to a youthful “triangular” face. The second, in the sub-lobule region is not so beneficial, but is simply excised; a manoeuvre common to both Baker’s7 and Waterhouse’s modified SMASectomy procedures.18

Technique

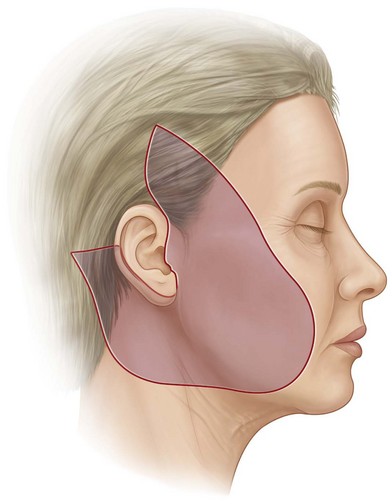

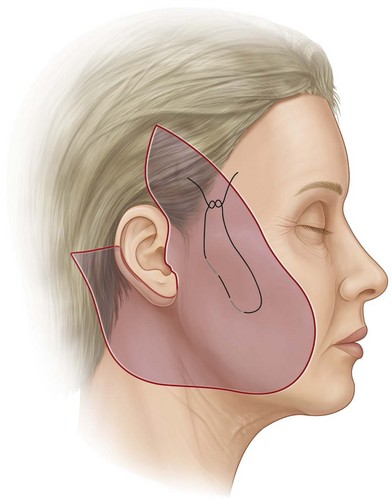

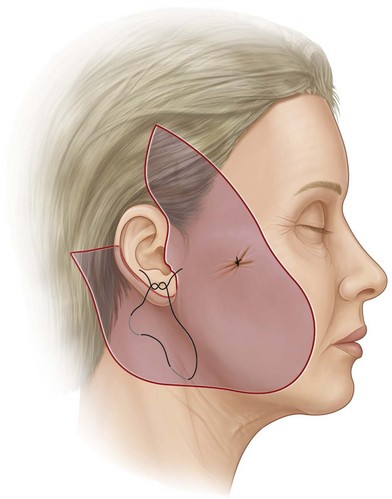

The surgical procedure is as follows: patients are prepared as for a standard facelift with tumescent infiltration (20 mL 0.5% bupivacaine and 1 mL 1 : 1000 adrenaline in 200 mL normal saline) into the subcutaneous plane. The incision extends vertically in the temporal scalp, along the anterior helical sulcus then passes post-tragal, and on occasion into the post-auricular sulcus (Fig. 11.3.1). A post-auricular extension is used where required and subcutaneous dissection tailored to each patient. The anterior SMAS is grasped in a postero-superior direction to provide a satisfactory effect on the jowl (Fig. 11.3.2). The key suture, using 2-0 PDS (Johnson & Johnson Medical Ltd), is then inserted to attach this SMAS to the relatively immobile pre-auricular parotid-masseteric fascia. Further sutures complete plication of the cervical platysma, below the mandibular angle, to the mastoid fascia (Fig. 11.3.3) and any surface irregularities are addressed by suture imbrication with 3-0 Vicryl (Johnson & Johnson). Excess SMAS in the infra-lobular region is excised, following hydrodissection, and closed with 3-0 Vicryl. Following meticulous haemostasis, excess skin, with low tension only, is trimmed and the wound closed over a small suction drain with 4-0 and 6-0 nylon. A light, compressive facelift dressing remains overnight and is removed with the drain the following morning. These can be similarly removed immediately prior to discharge in day-case patients. Sutures are removed at 4–6 days.

Evaluation

Patients and methods

In the authors’ practice, the PSP-lift was initiated in 2004 and an initial evaluation was performed on a consecutive cohort between August 2004 and May 2007. During this time, 122 patients were followed prospectively and specific assessment of outcome was performed. While specific, validated evaluation systems are available for surgical correction of the breast19 and upper limb,20 there is little available for evaluation of cosmetic facial surgery. Thus, a simple proforma (Table 11.3.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree