11.7 Facelift

SMAS with skin attached – the “high SMAS” technique

History

Triggered by the appearance of surface laxity, early attempts at facial rejuvenation focused on skin excision. Since the surface skin was sufficiently mobile to efface anterior redundancy, undermining and release seemed unnecessary. Limited peripheral skin excisions dominated the gestation period of facelifts,1–3 in the first quarter of the 20th century. While these procedures yielded improvement, they were limited in anterior effect and temporary in duration.

Seeking greater effect, Lexer4 lengthened and combined the separate temporal, preauricular and mastoid incisions. Bames5 later added skin undermining to further enhance the result. This concept of wide skin undermining dominated the thinking of the mid-20th century,6–8 and remains popular today.9,10

The presence of the subcutaneous facial mass may have been recognized as early as the 1930s by Pires.11 Pires placed suspension loops from the preauricular fascial to the anterior nasolabial fat in an effort to better efface anterior jowling. But the importance of specific suspension of the subcutaneous mass, in addition to skin redraping was best described by Aufricht in 196012: “In order to understand the mechanics of the sagging cheek, one must consider the behaviour of the skin and the areolar fatty layer separately. Both layers are subject to histo-morphological changes of their own. This fact is important. It indicates that the surgical correction for sagging cheeks generally requires a two phase procedure: (1) subcutaneous suspension (or lift), i.e., suspension of the fatty areolar layer; and (2) cutaneous suspension after the removal of excess skin.”

Patient consultation

The lower eyelid and upper cheek overlap, and as a result, they should be addressed together in the patient over the age of 40. The delicate lower eyelid is separated from the heavier cheek by two fascial partitions. The orbicularis retaining ligament13 (orbitomalar membrane14) extends from the junction between the pre-septal and periorbital portions of the orbicularis muscle to attach to the bony skeleton. The orbicularis retaining ligament (ORL) inserts into the orbital rim medially, then courses down and lateral onto the body of the zygoma. A second fascial partition, the malar membrane15,16 (zygomaticocutaneous ligament17) extends from the lower border of the periorbital orbicularis to insert in the malar bone below. Medially, the malar membrane origins align with the orbicularis retaining ligament at the medial tear trough. Laterally, however, it courses obliquely across the cheek, inserting into bone in the bare area above the deep origins of the upper lip levators. Together, these two partitions protect the eyelid suspensory apparatus from the weight of the cheek.

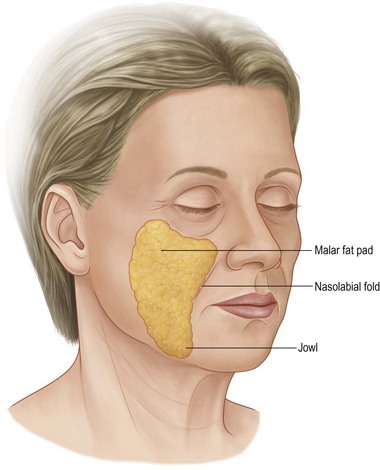

The specific sub-areas to be addressed are the malar prominence, the nasolabial fold, and the jowl (Fig. 11.7.1). The typical aging face shows descent of the malar portion of the subcutaneous mass, so that the maximal cheek prominence is sub-malar, rather than over the body of the zygoma. Anteriorly, the upper anterior portion of the cheek fat shelves over the fixed fusion plane at the nasolabial fold. And finally, the lower anterior fat accumulates along the jowl at the mandibular border. The analysis of the individual patient, involves identifying the extent of each of these changes.

Evolution of the “high SMAS” technique

Aufricht12 and others18 had pointed out the need to directly address suspension of the subcutaneous facial fat as an essential component of facelifting. I, therefore, went through a phase of skin dissection followed by suture plication, as described by Aufricht. My experience was that the initial facial contours of the nasolabial fold and jowl were improved. But in follow-up, only about one-half of the patients achieved a lasting correction. Moreover, using the dermis to secure the skin advancement still caused many patients to look “stretched”. My overall results improved, and some patients maintained a natural improvement, but the results were too inconsistent for my satisfaction.

In 1974, Tord Skoog published his classic text,19 in which he described a revolutionary facelift procedure. Undermining the skin and superficial subcutaneous mass together as a composite, the cheek mass was then re-suspended using the superficial subcutaneous fascia (later termed the superficial musculoaponeurotic system or SMAS20). This approach offered repositioning of the skin along with the superficial subcutaneous mass as a single unit, without placing tension on the skin. Unfortunately, Skoog died before he was able to work out the nuances to develop his concept into maximally effective procedure. But the concept of cheek repositioning while avoiding skin stretching was very appealing.

Other surgeons21,22 adopted Skoog’s basic idea, and set out to modify it. Their early attempts focused on the buccal and mandibular area, where the SMAS was more defined and more mobile. The upper cheek, or malar area, was left only dermal support.23 It seemed clear to me that such differential suspension – fascia in the lower face, and only dermal suspension of the malar portion of the subcutaneous fatty mass – would give incomplete repositioning of the malar prominence. And worse, over time, the weak dermal support would relax faster than would the lower fascial portion.

It was that dilemma that fostered our anatomic dissections in the late 1970s and early 1980s.24,25

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree