Summary

Normal eyelid structure and function is critical for ocular protection.

Multiple aesthetic subunits coalesce in the periocular region.

Complex anatomy can be broken down into two basic subunits: the anterior and posterior lamellae, each of which must be individually addressed during reconstruction.

Defects in the medial canthal region often involve the lacrimal outflow system which must be assessed and reconstructed if present.

15.1 Anatomical Considerations

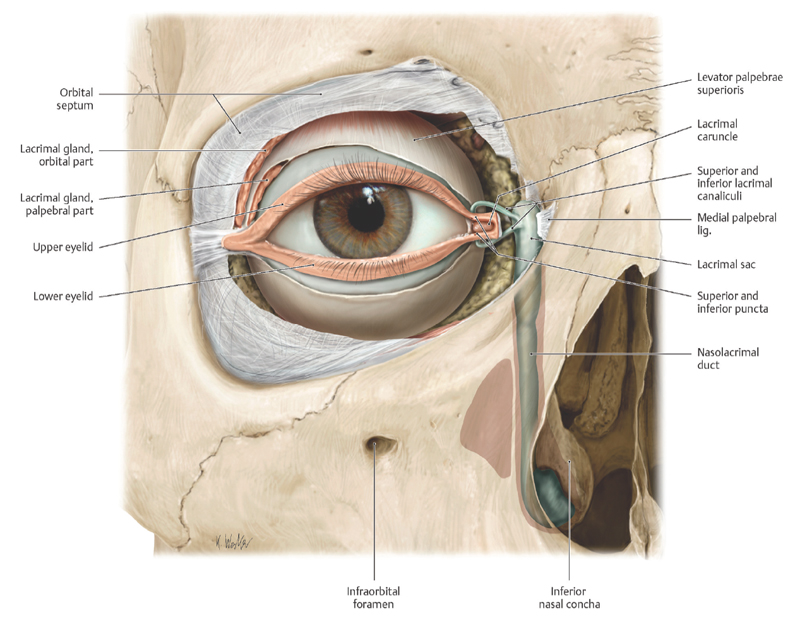

The complex anatomy of the upper and lower eyelids can be simplified for reconstructive purposes into the anterior and posterior lamellae. The anterior lamella consists of the skin and orbicularis oculi muscle and the posterior lamella consists of the tarsus and conjunctiva. The two lamellae have very specialized roles and, when full-thickness defects are present, must be considered and reconstructed individually (▶ Fig. 15.1). Partial-thickness defects often involve only the anterior lamella, leaving the critical posterior lamella tissues intact. The medial canthus houses the lacrimal outflow apparatus and includes the lacrimal punctum and the canaliculi of the upper and lower eyelids (▶ Fig. 15.2). Integrity of these structures is critical for normal lacrimal outflow and absence of epiphora. The medial and lateral canthi are the horizontal stabilizing structures of the upper and lower eyelids and when their integrity is violated, eyelid function is compromised and lack of a proper eyelid–globe interface ensues (▶ Fig. 15.3).

Fig. 15.1 Upper and lower eyelid anatomy. 1

(From THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Head, Neck, and Neuroanatomy, (c) Thieme 2016, illustration by Karl Wesker.)

Fig. 15.2 Lacrimal outflow anatomy. 1

(From THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Head, Neck, and Neuroanatomy, (c) Thieme 2016, illustration by Karl Wesker.)

Fig. 15.3 Canthal tendon anatomy. 1

(From THIEME Atlas of Anatomy, Head, Neck, and Neuroanatomy, (c) Thieme 2016, illustration by Karl Wesker.)

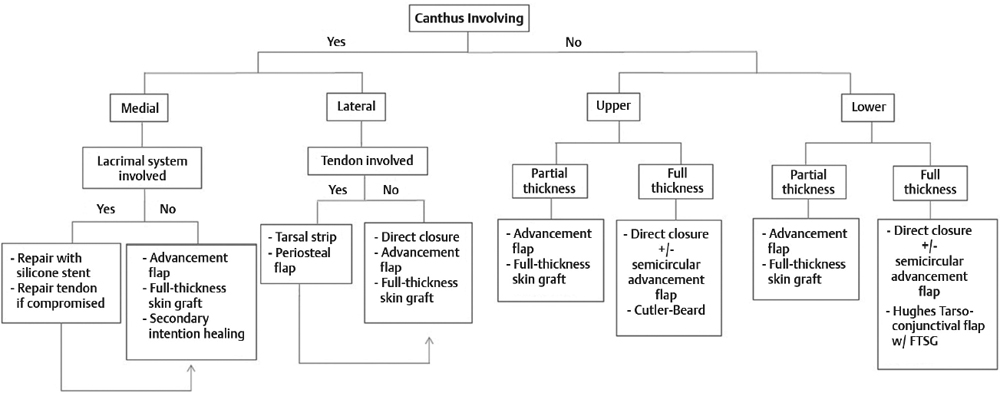

15.2 Algorithm for Closure

Approaches to eyelid defect closure can be separated into subgroups, which take into account special considerations based on anatomic localization (▶ Fig. 15.4). Defects involving the canthi can involve specialized structures in these regions. Defects in the medial canthus may or may not involve the lacrimal outflow system, particularly the puncta and canaliculi, and defects in both the medial and lateral canthal regions can affect the canthal tendons which provide anchoring and horizontal support to both the upper and lower eyelids. Defects of both the upper and lower eyelids not involving the canthi can be broadly grouped into partial thickness (involving the anterior lamellar structures) or full thickness (affecting both anterior and posterior lamellar structures).

Fig. 15.4 Algorithm for eyelid defect closure.

15.3 Defects Involving the Canthus (▶ Fig. 15.5)

15.3.1 Medial Canthal Defects

Defects involving the medial canthus have a high likelihood of affecting the lacrimal outflow system. Any suspicious defect close to the medial aspect of the upper or lower eyelids, or deep defects of the medial canthus, should be inspected for injury to the lacrimal outflow system and repaired primarily if possible (▶ Fig. 15.6a). Probing of the upper and lower puncta and canaliculi with a Bowman lacrimal probe can reveal occult injury to the lacrimal canaliculus (▶ Fig. 15.6b) and can often be primarily repaired with a silicone monocanalicular stent (▶ Fig. 15.6c,d). The canaliculi run through the medial canthal tendon which provides an anchor for, and horizontal support to, the eyelids. Concurrent injury is diagnosed as an easily distractable eyelid and repair is necessary to allow proper eyelid function. Pericanalicular sutures ensure re-approximation of the medial canthal tendon (▶ Fig. 15.7).

Fig. 15.5 Algorithm for closure of defects involving the canthi.

Fig. 15.6 (a) Large medial canthal defect in the region of concern for lacrimal outflow apparatus injury. (b) Lacrimal probing confirms injury of the lower lacrimal canaliculus. (c,d) Placement of a silicone monocanalicular stent to bridge the compromised canalicular segment.

Fig. 15.7 5–0 Vicryl pericanalicular sutures (anterior and posterior to the canaliculus) ensure reapproximation and repair of the medial canthal tendon, as the canaliculi run through the middle of the medial canthal tendon. 2

(Used with permission from Chen WP. Ocuplastic Surgery: the Essentials. Thieme, New York, 2001.)

After lacrimal system involvement is either ruled out or corrected as above, the surgeon has several options for the repair of medial canthal defect.

The medial canthus heals very well by secondary intention, and often times this approach is favored for small defects (typically 5 mm or less in diameter) in the natural depth of the medial canthal concavity. Advancement flaps and thick full-thickness skin grafts can partially obliterate this natural concavity and lead to a poor aesthetic result. Larger defects in this area are amenable to a variety of reconstruction options. One must bear in mind that the medial canthus is a site where multiple aesthetic units coalesce. The thicker skin of the lateral nasal wall should be reconstructed with like thicker tissue and involvement of eyelid skin in this area is best addressed with thin eyelid skin or an appropriate substitute such as retroauricular skin.

Defects involving the medial canthal lateral nasal wall tissues are nicely reconstructed with local advancement flaps of like tissue. The bilobed flap is a versatile tool for reconstructing moderate-size defects in this area and allows advancement of similar thick tissue from the glabella and nasal dorsum (▶ Fig. 15.8). The first lobe is sized according to the defect being addressed, and when oriented 90 degrees to the defect will allow this closure scar to fall in the corresponding vertical glabellar furrow. This lobe can be conservatively thinned if needed to improve thickness match without sacrificing integrity (▶ Fig. 15.8b). The second lobe is sized 50% smaller than the first lobe in width and situated 90 degrees away from the first lobe. This allows the closure scar to fall within, or in close proximity to, the horizontal glabellar fold. Dissection of the flaps is in the subcutaneous fat plane to prevent excessively thin flaps which can be lost, and also to avoid injury to the deeper structures, particularly the corrugator and procerus muscles in this region.

Fig. 15.8 (a) Medial canthal defect with planned bilobed flap closure. See 15.17a as well. (b) Conservative flap thinning, avoiding excess thinning and potential loss of viability. (c) One-week post-op with healing incisions oriented in the vertical and horizontal glabellar folds. (d) Two years post-op.

Larger and more inferiorly positioned medial canthal defects can be addressed with cheek advancement flaps, utilizing a lateral rhinotomy incision coupled with an incision hidden in the orbital rim ligament depression which can recruit significant thick skin for medial canthal reconstruction (▶ Fig. 15.9a). Dissection once again is in the subcutaneous fat plane to maintain a thick viable flap, yet avoid damage to the underlying facial mimetic muscles (▶ Fig. 15.10b). The depth of the medial canthus is often best left to heal by secondary intention which, as noted earlier, often results in an excellent final aesthetic result (▶ Fig. 15.9c-e).

Fig. 15.9 (a) A lateral rhinotomy incision coupled with a lateral incision along the tear trough for planned reconstruction. (b) Dissection of a thick flap in the subcutaneous plane. (c) Closure with a small area in the depth of the medial canthus left to heal by secondary intention. (d,e) Six weeks with almost full epithelialization of the area of secondary intention healing.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree