CHAPTER 12 Eyelid Reconstruction

Introduction

Reconstruction is based upon the surgical principles that you are already familiar with. These principles are covered in the section “Repair of Soft Tissue Trauma,” in Chapter 13. The goal of the reconstruction is to restore the normal anatomy and function. You will be impressed by how quickly you can learn successful eyelid reconstruction techniques.

If you find that pulling the edges of the eyelid wounds together creates a great deal of tension, you will need to perform canthotomy and cantholysis to allow the lateral portion of the lid to slide over. Larger full-thickness lid defects require special techniques for closure. Using the Tenzel flap or Hughes procedure, you will be able to repair lid margin defects of between 50% and 100% of the lower eyelid. If you are interested in having an active practice in skin cancer removal and eyelid reconstruction, you should learn all of the techniques that we have discussed thus far. With some experience, you will learn to modify these procedures and use them in combination. More advanced procedures such as the Mustarde cheek rotation and median forehead flap are used to cover large anterior lamellar defects.

Fundamentals of eyelid anatomy

Eyelid margin

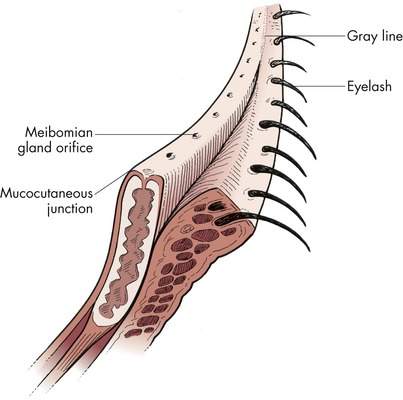

The eyelid margin is an anatomic structure that we take for granted until we have to repair it. To repair a lid margin defect, you must know the eyelid margin architecture. We have discussed this in detail, but refer to Figure 12-1 to refresh your memory. Recall that the eyelid margin is a flat platform with nearly right angles at the anterior and posterior edges of the eyelid. From posterior to anterior, the anatomic structures that you should know are:

Lateral canthus

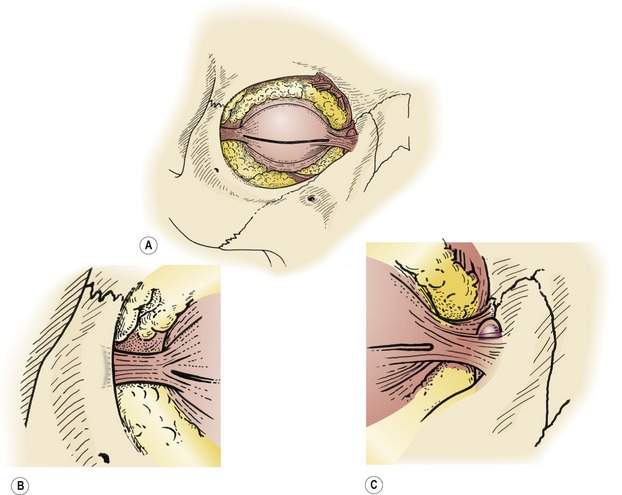

The lateral canthus is relatively simple anatomically. The upper and lower crus of the lateral canthal tendon extend from each tarsal plate to form the lateral canthal tendon. The lateral canthal tendon inserts at Whitnall’s tubercle on the inner aspect of the lateral orbital rim approximately 10 mm below the frontozygomatic suture (Figure 12-2). Although the lateral portion of the eyelid is attached to the rim mainly by the lateral canthal tendon, contributions from the orbicularis, orbital septum, levator aponeurosis, and lower lid retractors provide additional support for the eyelids.

Think of the lateral canthal tendon as a Y. A cantholysis converts the Y of the lateral canthal tendon into a V. To release the lateral aspect of the lid, you must cut the respective crus of the lateral canthal tendon. Think of this as now cutting one leg of the V off the orbital rim (see Figure 13-15). Often you must make some additional cuts when performing the cantholysis to mobilize the lid. These cuts release the septum, orbicularis, and lower lid retractors, the other contributions to the lateral canthus that we just mentioned. You learned to do this when you performed a lateral tarsal strip procedure.

Reconstructing a lateral canthus is simple, anatomically. Remember to reattach the reconstructed tissues on the inside of the lateral orbital rim so that the eyelid margin rests against the curve of the eye. Usually you can reattach the lateral canthus to the periosteum of the bone. If there is no periosteum present, you may have to make small drill holes in the lateral orbital rim to attach the lid.

Medial canthus

The medial canthal tendon is anatomically more complex than the lateral canthal tendon. The anterior and posterior limbs of the medial canthal tendon surround the lacrimal sac (see Figure 12-2). The anterior limb of the medial canthal tendon attaches to the frontal process of the maxilla. The posterior limb of the medial canthal tendon attaches on the posterior lacrimal crest. A tough layer of tissue known as the lacrimal fascia surrounds the sac, fusing with the periosteum of the orbital rim and periorbita of the orbital walls. Disinsertion of the anterior limb of the medial canthal tendon will not change the position of the lower eyelid. An intact posterior limb of the medial canthal tendon will support the canthus and is required to pull the medial aspect of the eyelid posteriorly to follow the curve of the eye.

Description of the postexcision defect

• Full-thickness defect of the central 25% of the lower eyelid

• Full-thickness defect of the lower eyelid involving the lateral 50% of the eyelid, including the lateral canthal tendon

• Anterior lamellar defect over the inferior orbital rim measuring 1 cm by 1.5 cm

• Full-thickness defect of the upper eyelid involving the medial one third of the lid, including the punctum and canaliculus

Treatment of malignant cutaneous tumors

Biopsy techniques

If you suspect an eyelid malignancy, you already know to perform an incisional biopsy to confirm your diagnosis. The techniques of incisional biopsy were discussed in Chapter 11.

Tumor excision

Frozen section control

Ideally, your first several excisions for cutaneous malignancies should be performed on well-demarcated small nodular basal cell carcinomas. Outline the area of clinical involvement with the surgical marker. Draw a second ring around the tumor, marking an additional 3 mm of clinically uninvolved skin to be removed. Excise the tumor using the most peripheral marking. Orient the tissue for the pathologist with a suture. If frozen sections show residual tumor, re-excise the area of involvement. When the surgical margins are tumor free, you can reconstruct the eyelid. Often, surgeons will begin reconstruction while the frozen sections are being processed and analyzed. If you need a refresher on the excision technique, refer back to Figure 11-36.

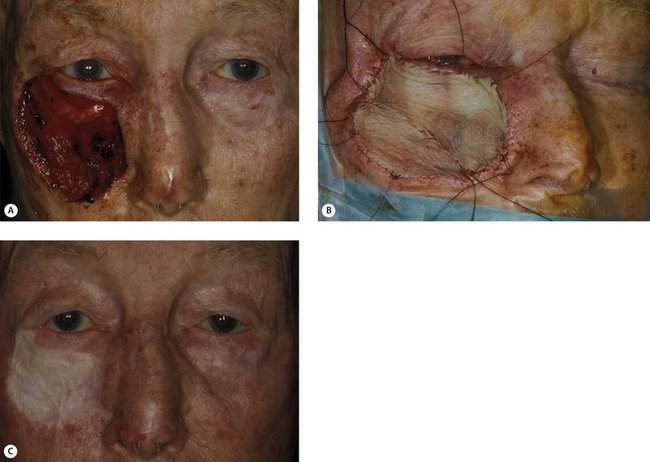

As you gain experience, you may choose to excise larger nodular basal cell carcinomas. As your ability to perform larger, more complicated reconstructions improves, you can excise morpheaform basal cell carcinomas or squamous cell carcinomas (Figure 12-3). Remember that the margins of these more aggressive tumors are indistinct. The postexcision defect can be large in many patients.

Anterior lamellar defects

Options for repair

We will talk about the advantages and disadvantages of each technique. For many defects, more than one technique may work. You will learn to choose the best technique for the particular defect. Small lesions away from important landmarks will heal by granulation over time. Although successful in some patients, the healing may take weeks to months. Scar contracture can result in distortion of anatomic landmarks. Primary closure with or without undermining is generally a better option. Myocutaneous advancement flaps are the best choice for larger anterior lamellar defects. Free skin grafts give the least acceptable result, but allow you to cover any size anterior lamellar defect. If you cannot perform a more aesthetically acceptable procedure, you can always use a skin graft, so it is important to learn the technique.

Primary closure

Primary closure can be performed if redundant skin exists adjacent to the defect. Areas of the face that typically have redundant skin include the glabella, the upper lid skin fold, and the temple. There is normally little redundant skin in the lower eyelid or medial canthus. You will also learn to appreciate how the amount of redundant tissue varies from one patient to the next. The patient with wrinkled and sagging skin has plenty of redundancy to help you close small defects. In the patient with sun-damaged, tight skin with no wrinkles despite advancing age, more than primary closure will be required for all but the smallest defects (Figure 12-4).

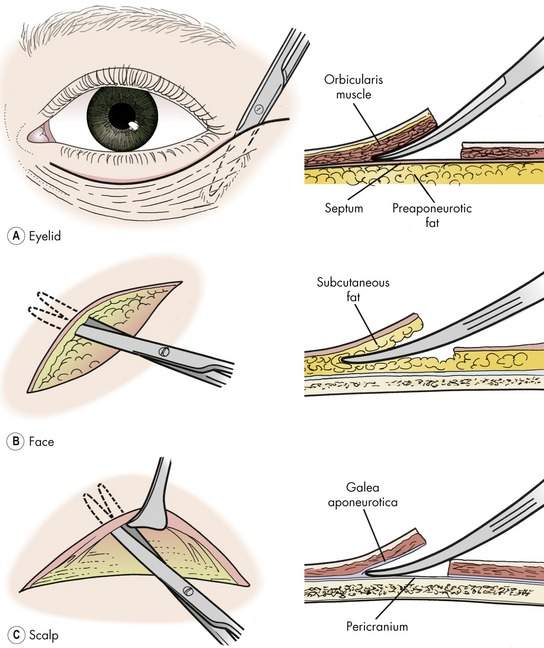

Primary closure with undermining

Primary closure with undermining is commonly used to close lesions away from the eyelid margin. You must know the level to undermine to mobilize tissue, preserve blood supply, and avoid nerve damage (Box 12-1). Within the orbital rims, any tissue undermining should be done in the preseptal plane. Outside the orbital rims, undermining should be done in the subcutaneous tissue plane. Be especially careful when undermining any tissue in the path of the seventh nerve extending from the tragus of the ear to the tail of the eyebrow. The facial nerve is superficial as it crosses over the zygomatic arch. When closing areas in the forehead or scalp, you should undermine deep to the frontalis muscle in the loose areolar tissue superficial to the periosteum. You will find that extensive undermining is usually necessary to mobilize skin in the scalp or forehead (Figure 12-5).

Box 12-1 Tissue Planes for Reconstruction

When reconstructing the lower lid, minimize any vertical traction on the eyelid by closing wounds to leave a vertical scar. Although the vertical scar does not blend in with the natural skin creases, this technique will avoid ectropion or lid retraction (Figure 12-6).

Free skin grafts

Full-thickness skin graft

The term full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) means that an entire thickness of the epidermis and dermis has been removed for transfer. The floor of the donor site is usually subcutaneous fat. The donor site must be closed surgically, which limits the size of the graft available for transfer. All the skin appendages are contained within the donor skin, so you should choose a hairless donor site for obtaining the graft. FTSGs heal with less shrinkage than split-thickness skin grafts, making the full-thickness technique better suited for eyelid reconstruction where shrinkage can cause ectropion, lid retraction, or lagophthalmos.

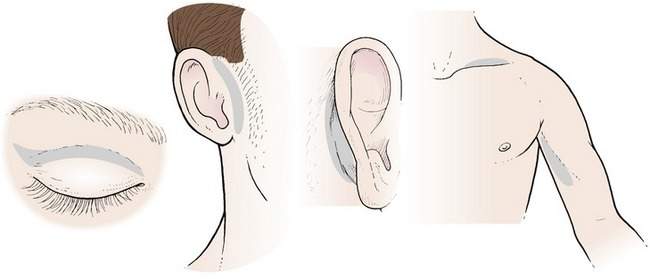

Donor sites include (Figure 12-7):

When possible, donor skin of the same color, texture, and thickness should be picked for transfer. Upper eyelid skin is the best choice for reconstructing eyelid defects. From a practical point of view, this skin is seldom used for fear of creating upper eyelid skin fold asymmetry or lagophthalmos. When the situation permits, grafts can be taken from both upper eyelids to obtain sufficient skin and maintain symmetry. The results of full-thickness skin grafting with upper eyelid skin are good (refer back to Figure 3-11).

The traditional donor site is retroauricular skin. However, it is difficult to work behind the ear and somewhat uncomfortable for patients postoperatively. Preauricular skin is similar to retroauricular skin in character and is much easier to harvest. Slightly less skin is available, but the 15 mm by 40 mm area from the preauricular site is well suited in size and shape for most eyelid grafting. We discussed the technique of preauricular skin grafting in Chapter 3, so I’ll review it only briefly here.

Graft survival is usually high when the FTSG is placed on a healthy bed of tissue. The graft will often look dark at 1 week. Normal color and texture will return several weeks postoperatively. A small amount of shrinkage of the graft is expected (Figure 12-8). FTSGs do not take well on bare bone.

Split-thickness skin graft

The main advantage of a STSG is that a large area of skin may be harvested because no skin closure is required. Split-thickness skin will usually survive on bare bone, especially if the cortical bone is burred to create some bleeding. The donor skin is thin, and considerable shrinkage is always seen (Figure 12-9). The color, texture, and thickness are often a poor match for eyelid skin. As you might guess from this description, STSGs are used only if the defect is too large for a FTSG and there is no myocutaneous flap that is practical for closure.